The current issue of Empire, on sale now, features Hugh Jackman's Wolverine on the cover, with exclusive interviews from the set of the film. To mark the issue, we delve into Logan's tumultuous comic-book history.

Buy the Logan issue of Empire online here{

Subscribe to Empire here{

The Interstate 5 begins at the Mexican border, snaking up the entirety of the USA’s west coast to Canada. If you’re lucky you can get from San Diego to Los Angeles in an hour, but on this afternoon in July 1982, it was taking forever. Chris Claremont, who had been chief writer of the X-Men comics since 1975, was driving a gang of the industry’s finest back from Comic Con, accompanied in the front by Frank Miller, who has spent the past three years writing and pencilling Daredevil. Claremont had wanted Miller to take up drawing duties on a limited, solo Wolverine series, but Miller had turned it down. “I’d said, ‘Hey, wanna do a Wolverine?’” Claremont tells Empire. “And he’d just said, ‘Nah.’”

Since joining the X-Men in 1975, Wolverine had been a huge hit with readers, who loved his no-nonsense claw-slicing, but seven years on, Claremont was beginning to find him a little tiring. The beast was becoming boring. “Everyone was used to seeing him as a cliché, as just the monster. That was why Frank didn’t wanna do it, he didn’t wanna do four issues of Wolverine just hacking and slashing and farting around. And I didn’t wanna do that either. Any idiot can do that. It’s fun perhaps to draw, but so what?”

I had thought briefly about Badger, but I decided that Wolverine sounded better.

On Interstate 5, there was the tailback to end all tailbacks. Border cops were stopping everyone, looking for illegal immigrants, so Claremont and co were going to be on the road for the long haul. Claremont, meanwhile, had recently come up with an idea to breathe life into Wolverine, to make him three-dimensional. To find the man behind the monster. “So,” he says, “I trapped Frank on this car-ride and made the pitch.” Over three hours, while a rabble of other writers and artists babbled in the back, Claremont outlined to Miller his vision for a new, more mature journey for the character. It would mean taking Wolverine to Japan, where he would face defeat, get his heart broken, and find honour. And fight a load of ninjas. Miller loved it. And that was when the Wolverine was truly born.

Wolverine is not your average superhero. As drawn in the comics, he’s a stout 5 foot 3 inches, an angry, antisocial, cigar-chomping, hard-drinking bit of rough. His skeleton and claws infused with near-indestructible adamantium, when the situation calls for it he rages hard, sometimes to his shame. After enjoying over two decades of popularity in print, he became just as iconic on screen to the extent that, even if he has nothing to do with the story, Fox will squeeze a gnarly Wolverine cameo into every X-Men film (telling Charles and Erik to go fuck themselves in First Class, slaughtering a small army in Apocalypse). He’s a noble savage, the meanest mutant there is. Yet he could have been a badger.

When Marvel Comics’ Editor-in-Chief Roy Thomas took over from Stan Lee in 1972, the X-Men line, due to shaky sales, had been cancelled. Comics were doing well in Canada though, and Thomas wanted to capitalise on that by creating a Canadian character. Having once wanted to be a zoologist, he took inspiration from some of the country’s animals. “I wanted an animal that, while it might also be in the United States, was native to Canada,” says Thomas, now 76, but still sounding like an exuberant Missouri kid. “I couldn’t use a moose. I had thought briefly about Badger, but I decided that Wolverine sounded better. Badger sounds like you’re just bothering or annoying somebody, and Wolverine has a wolf-like sound to it.”

So Wolverine it was. “Wolverines were small yet very fierce, noted for attacking animals far larger than themselves,” he continues. “So I wanted him short, fierce and bad-tempered. Everything else I pretty much left to Len Wein.” Wein, one of Marvel’s top writers and about to take over as Editor-in-Chief, took Thomas’s idea and, alongside artist John Romita, Sr, created Wolverine. Wein and Romita looked up wolverines in the office encyclopaedia, saw the claws and acted accordingly.

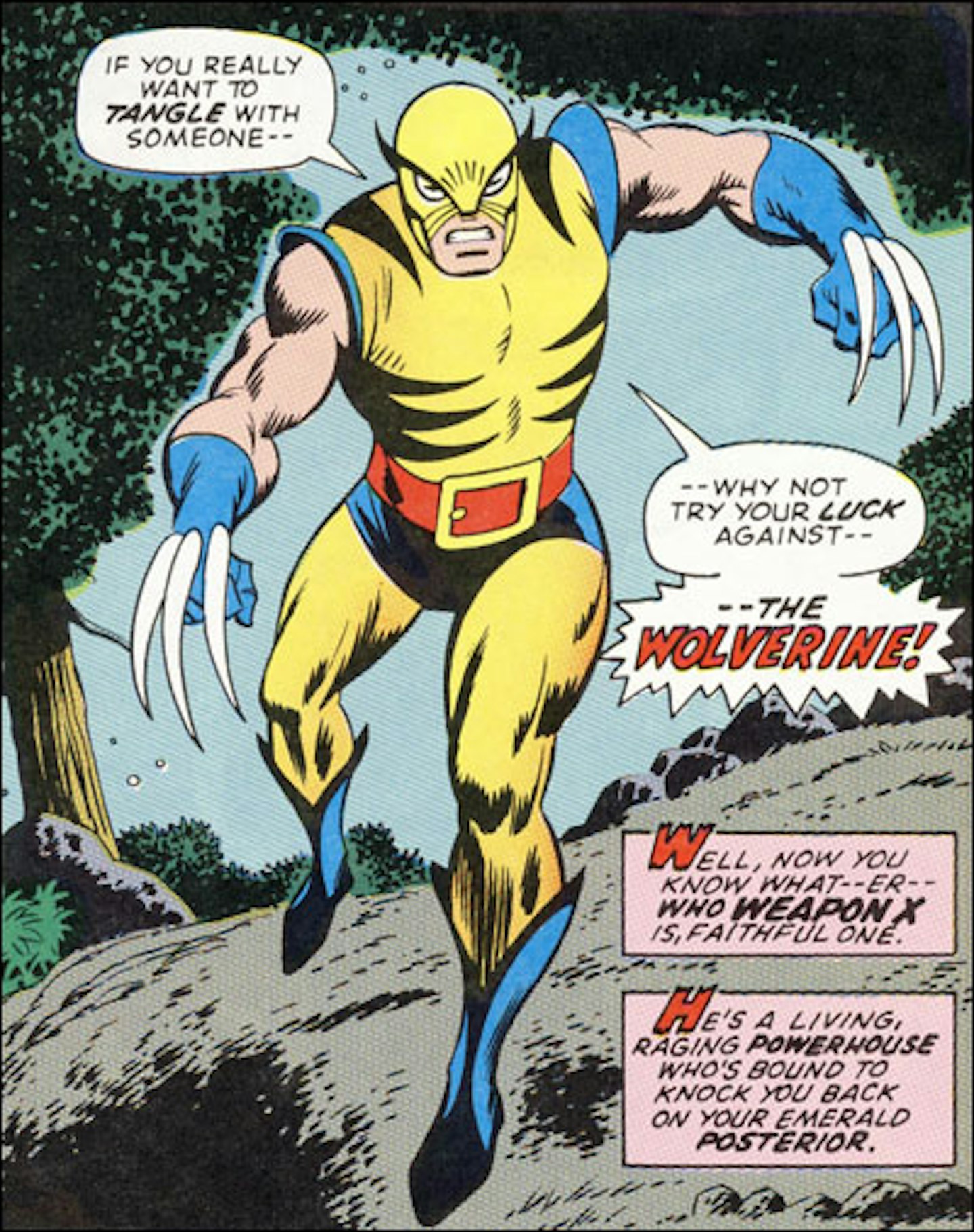

He made his first appearance in a couple of issues of The Incredible Hulk at the end of 1974, introduced as ‘Weapon X: A living, raging powerhouse,’ an agent working for the Canadian government, sent to take down the Hulk after he crossed into Quebec. “Like a wolverine, I’ve got claws,” he announced, “forged of diamond-hard adamantium – and the power to back them up!” Thomas had invented the fictional metal for Ultron’s outer shell in Avengers 66 (July 1969), and Wein thought it made sense for Wolverine’s claws – then, though, they were just a retractable part of his gloves. Wein gave him mutant powers: strength, speed, resilience and animal senses, and Wolverine joined the X-Men in February 1975.

He’s a person bared down to essentials. ‘What’s your name?’ ‘Logan.’ ‘First or last?’ ‘Yes.’

After that, Claremont became the X-Men writer, with Dave Cockrum pencilling, and the pair fleshed out Wolverine. They made him older, gave him his healing powers, and Cockrum drew him without his mask, giving him the sideburns, and a hairdo to match the headpiece. With his face finally revealed, Claremont named him Logan. “I didn’t want him to have a binary name,” he says. “He’s not John Smith. Or Clark Kent. He’s a person bared down to essentials. ‘What’s your name?’ ‘Logan.’ ‘First or last?’ ‘Yes.’” Claremont and Cockrum also made the claws part of his anatomy, thus making the man, rather than the costume, the hero. But it was important, says Claremont, that to pop those claws hurt. Absurdly, it humanised him. “Every time you extend the claw, you’re stabbing yourself,” says Claremont. “To get to the point where he can actually do damage in a fight, he’s got to slash himself open from the inside out.”

Stan Lee has said Wolverine almost singlehandedly kept people fascinated by the X-Men. Mark Millar, who wrote Ultimate X-Men, as well as the Enemy Of The State and Old Man Logan Wolverine series during his stint at Marvel in the 2000s, agrees, and puts it down to timing. “The Punisher [also created in 1974] and Wolverine are very dark characters,” he says. “They’re antiheroes, unlike the stuff that was created in the early ‘60s and they’re more reflective of the period they were created in, where the president was potentially going to jail. Wolverine was the first hero we’d ever seen do anything like that before. Even Batman would just knock guys out; Wolverine has metal claws and he kills people.”

By the early ‘80s, though, Claremont was getting uncomfortable with him being a two-dimensional psycho. So in 1982, he took him to Japan, where a rigidly structured society would challenge the animal part of his nature. Influenced by Kurosawa films, by the Lone Wolf And Cub films, and by samurais in general – the combination of extreme violence and a code of honour – Claremont began to split him into two, a duality personified by the Wolverine story’s two love interests: the elegant Mariko, and ninja Yukio.

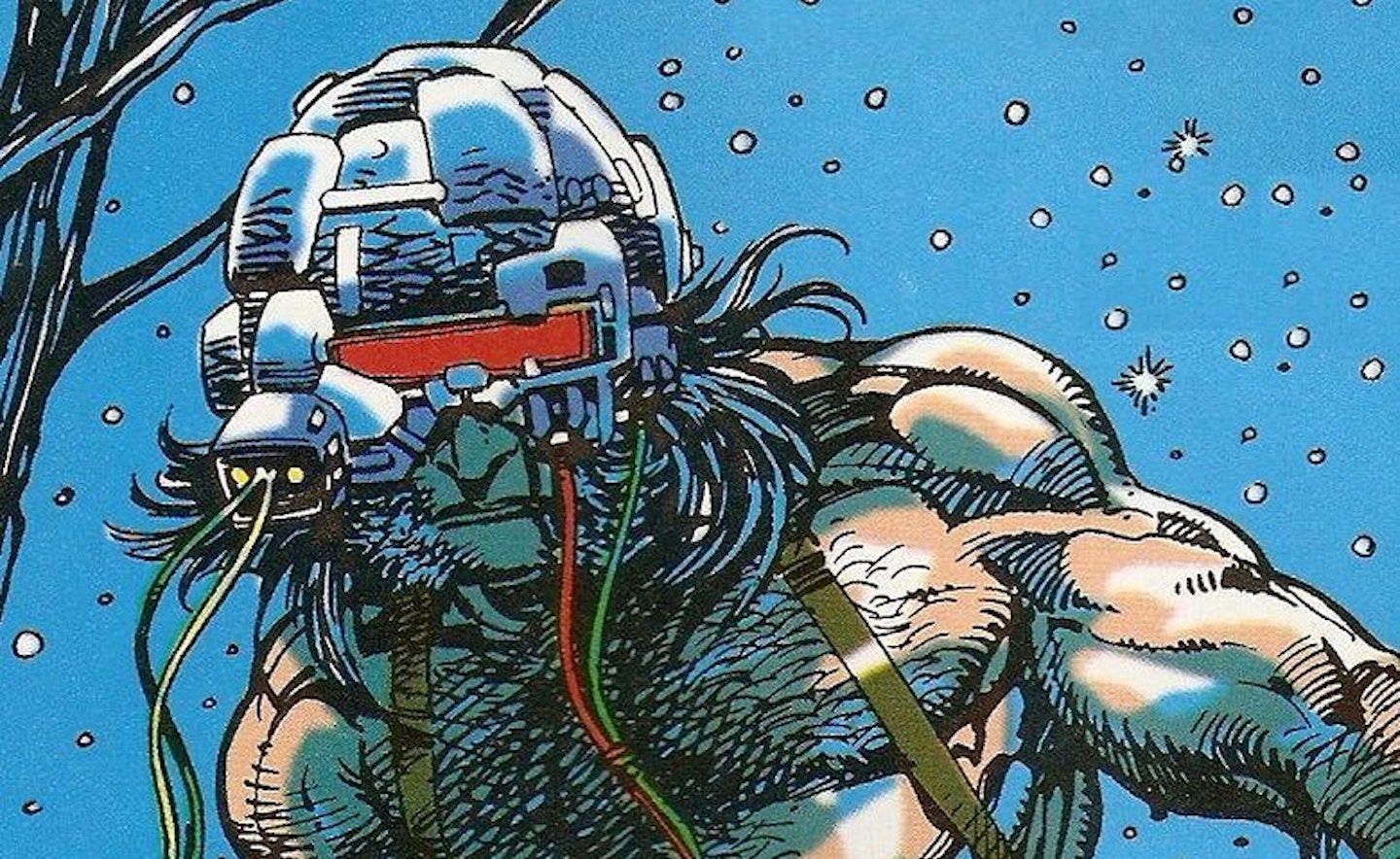

The series was an enormous progression from the goofier X-Men series it had sprung from – in retrospect it feels like the moment mainstream comics grew up. However, Millar cites the 1991 series Weapon X, written and drawn by Barry Windsor-Smith, as the biggest influence on his own Wolverine stories. In the retconned saga, Windsor-Smith introduced the idea that Logan’s entire skeleton had been forcibly laced with adamantium, turning him into a government weapon. It’s a ghastly medical experiment, and the series is cold, brutal, and entirely unsentimental, with Wolverine suffering/inflicting (pick one) extreme beserker rages. “His entire character is there,” says Millar. “That tragic nobility, the ferocious violence but with a poet’s heart in the middle of it.” 20th Century Fox love it so much they’ve visited it three times on screen – as flashbacks in X2, as part of the backstory in the X-Men Origins: Wolverine film, and in slicing, dicing glory in the Apocalypse cameo.

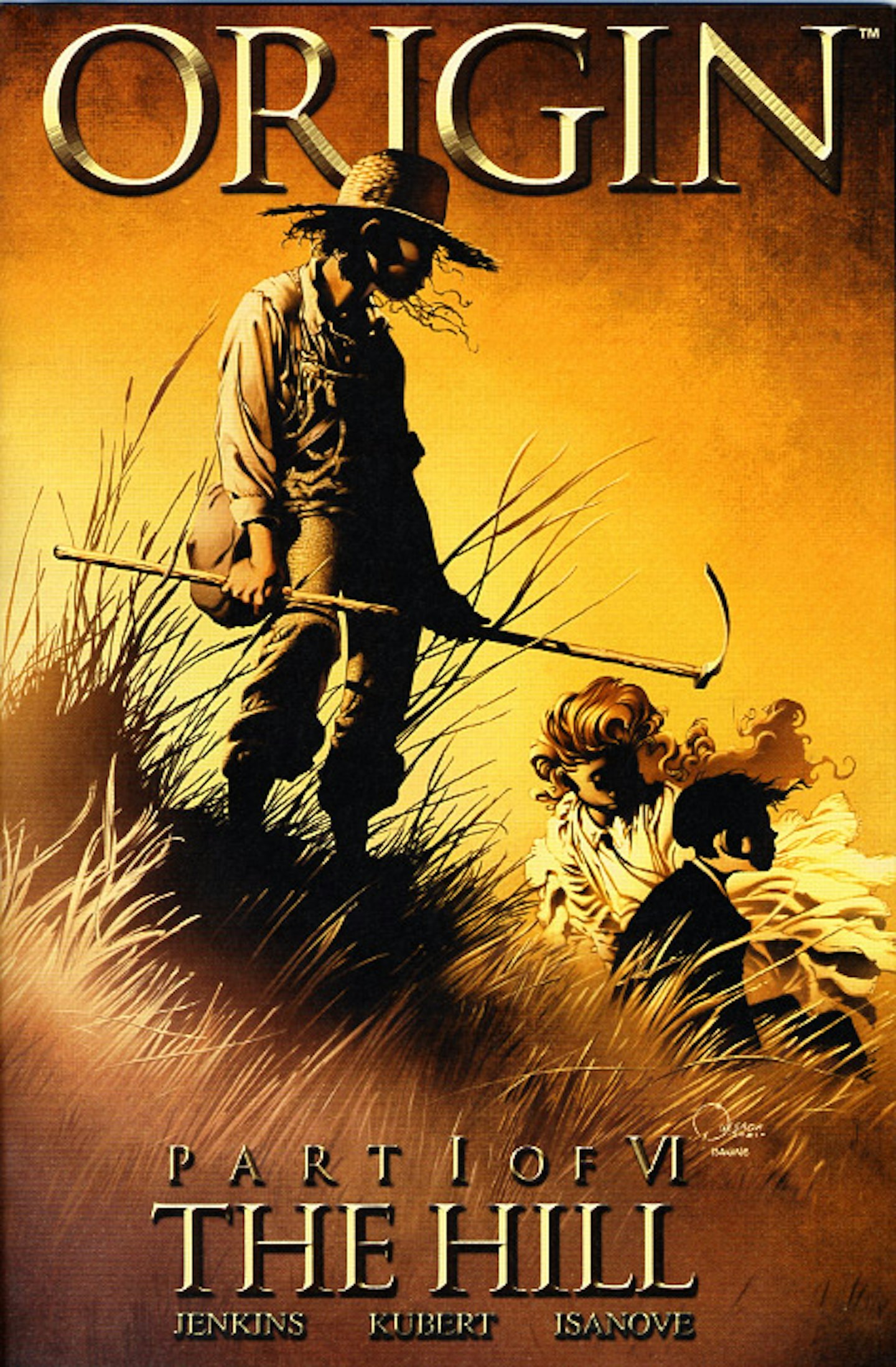

The Weapon X episode is now canon, and there have since been various backstories given to Logan. For decades he was a man without a past, which made his allure all the greater. But in 2001 Marvel published the six-issue series Origin, which went back to his childhood, introducing him as a young boy called James Howlett, familial son of a virtuous, wealthy estate owner, but illegitimate son of the groundskeeper, Thomas Logan, who kills James’s father. James, who discovers his mutant bone claws when he gets angry, kills Thomas Logan, goes on the run, ends up accidentally killing the love of his life, then retreats into the mountains with a pack of wolves. It’s a ripping yarn, but it undeniably steals the romance from the character.

Mark Millar says he was in the room when the idea for the story came up, and says it sprung from poor sales, which led to numerous wheel-reinventions. Claremont groans deeply when Empire brings up both Weapon X and Origin. “My approach to Logan was always that what matters to him is the present, and by extension the future. He doesn’t ever look back. Because what’s done is done. My thought was that we should only reveal what was necessary for a specific story. Then, when Bill Jemas [who was running Marvel] said, ‘Why don’t we do an origin for Wolverine?’, my point was that once you’ve done it, you’re stuck with it. And you can’t ever go back. The joy of Wolverine is that there’s a mystery.”

Regardless, Wolverine’s early life was set in stone for his cinematic incarnation, and you’d be hard pushed to find anyone who doesn’t love Hugh Jackman’s take on the character. Roy Thomas, Chris Claremont and Mark Millar all tell Empire that he perfectly embodies Wolverine, despite being a foot taller than his print counterpart. Years earlier, though, Claremont wanted someone entirely different – and the mouth waters.

In 1990, Claremont and Stan Lee were talking to James Cameron about producing an X-Men film. Cameron wanted Kathryn Bigelow – who was then directing Point Break – to helm it, and Total Recall’s Gary Goldman to write it. “I was fantasising about Bob Hoskins as Wolverine,” says Claremont. “Bob was in his prime. And he was the right height. There’s this really silly Tom Selleck movie called Lassiter where Selleck plays a thief in London in the 1930s. Bob Hoskins is the detective chief inspector, and there’s a moment where Selleck comes to his door and knocks on it and Hoskins opens the door and just goes, ‘Aarrooooargh!’ Total east London. ‘You come to my house?!’ And he just punches Selleck down the path. Four slaps to the chest. Boom boom boom boom. And Selleck looks scared. ‘You come to my house?!’ He just keeps repeating it. ‘How dare you?!’ And I thought, ‘Yeeeeah! Give him claws and the world is good.’”

This is news to Millar. “Oh my god!,” he squeals. “That actually is kind of perfect! Bob Hoskins is a tiny hairy testicle, he oozed masculinity. He was small, but you feel he could sort of kick the shit out of everyone regardless. Think of him, his eyes going wide and his nostrils flaring.” Alas, Stan Lee then mentioned Spider-Man, and Cameron got sidetracked writing drafts for that, and the X-Men film disappeared until Bryan Singer jumped on a few years later.

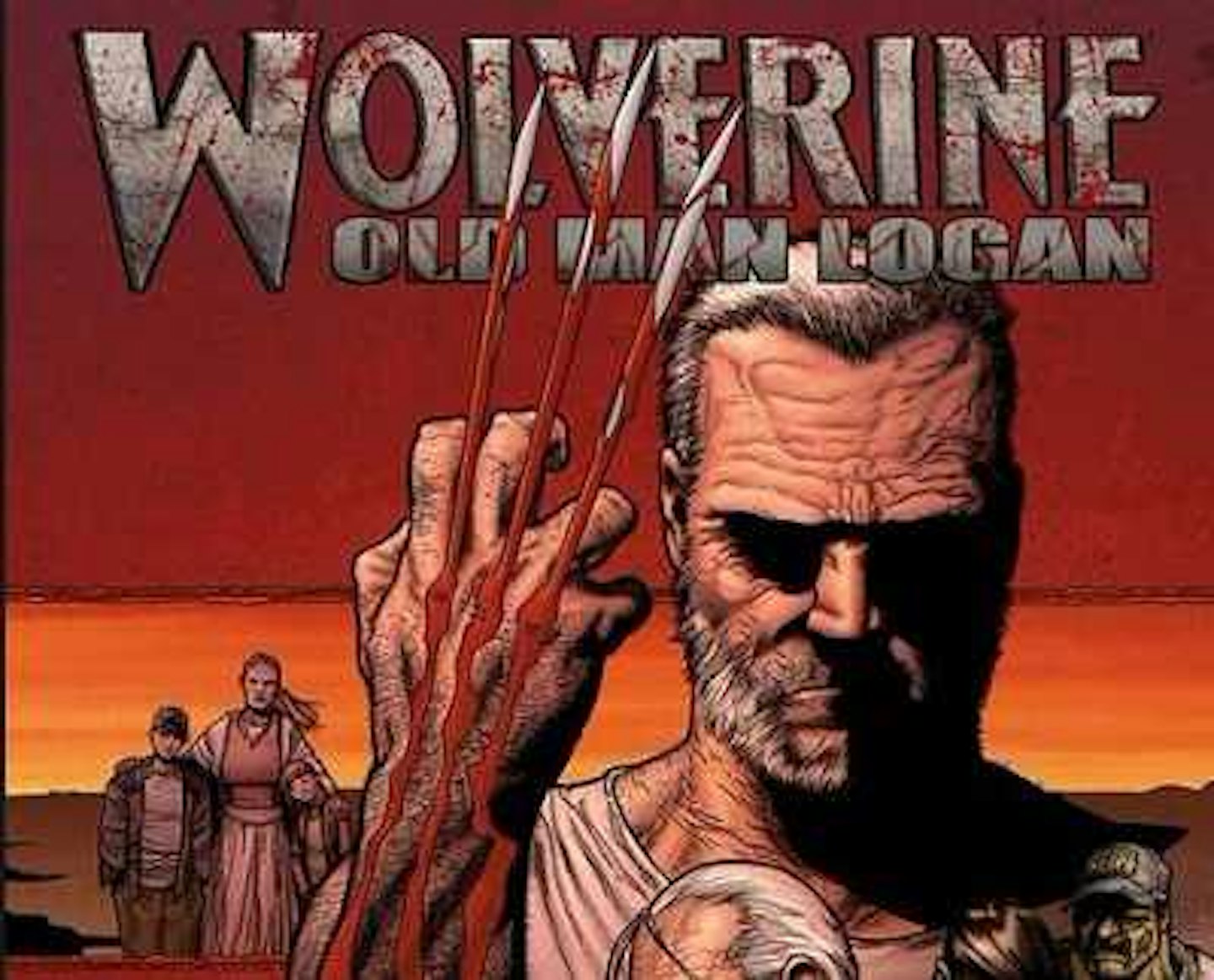

Millar loved Jackman in the films, but felt that in the comics he had lost his edge, becoming too paternal, “almost grandfatherly.” In 2005’s Enemy Of The State, in which he’s brainwashed by Hydra before SHIELD fix him, Millar has him slaughtering thousands (on both sides). And he went even wilder with 2008’s Old Man Logan, which found Wolverine 50 years in the future, leading a simple life in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, a downtrodden pacifist refusing to pop his claws after unimaginable trauma. Millar always saw early Wolverine as a version of Clint Eastwood’s The Man With No Name, and Old Man Logan was his take on Unforgiven. It’s about as perverted as Marvel have got, with all the good guys dead, and the Hulk’s inbred family of rednecks running California like ganglords. When the violence comes, it’s extreme and bizarre. Millar’s comics had been selling so well, he says, Marvel were letting him do whatever he wanted. “So even the most objectionable stuff in Old Man Logan, nobody batted an eyelid. The Hulk's fucking his cousin, and they were like, 'Yeah that sounds good, go ahead.'”

Millar’s story served as the germ of the new Logan film but, needless to say, much of the perversity is absent. Jackman, meanwhile, says this is his last outing of the character. But you can bet it won’t be the last we see of Wolverine on screen: his appeal as strong as ever. The key, says Claremont, is not about what he does, but what happens to those around him. “There is no way one can interact with Logan on any level and not be changed,” he says. “And the sad realisation is, any change to oneself deriving from Logan will be an echo of him. You don’t come out of it nicer. You come out of it more of his lethal weapon. And I guess you could say that would make him a toxic environment, especially for heroes. But for dealing with contemporary reality and the villains to go up against, he’s a man you need as the axle around which the heroic wheel rotates.”

Wolverine was created in a dark, uncertain time of political upheaval. We don’t want him going anywhere.

The Logan issue of Empire is on sale now. Buy it online here. Logan is in cinemas from 1 March.