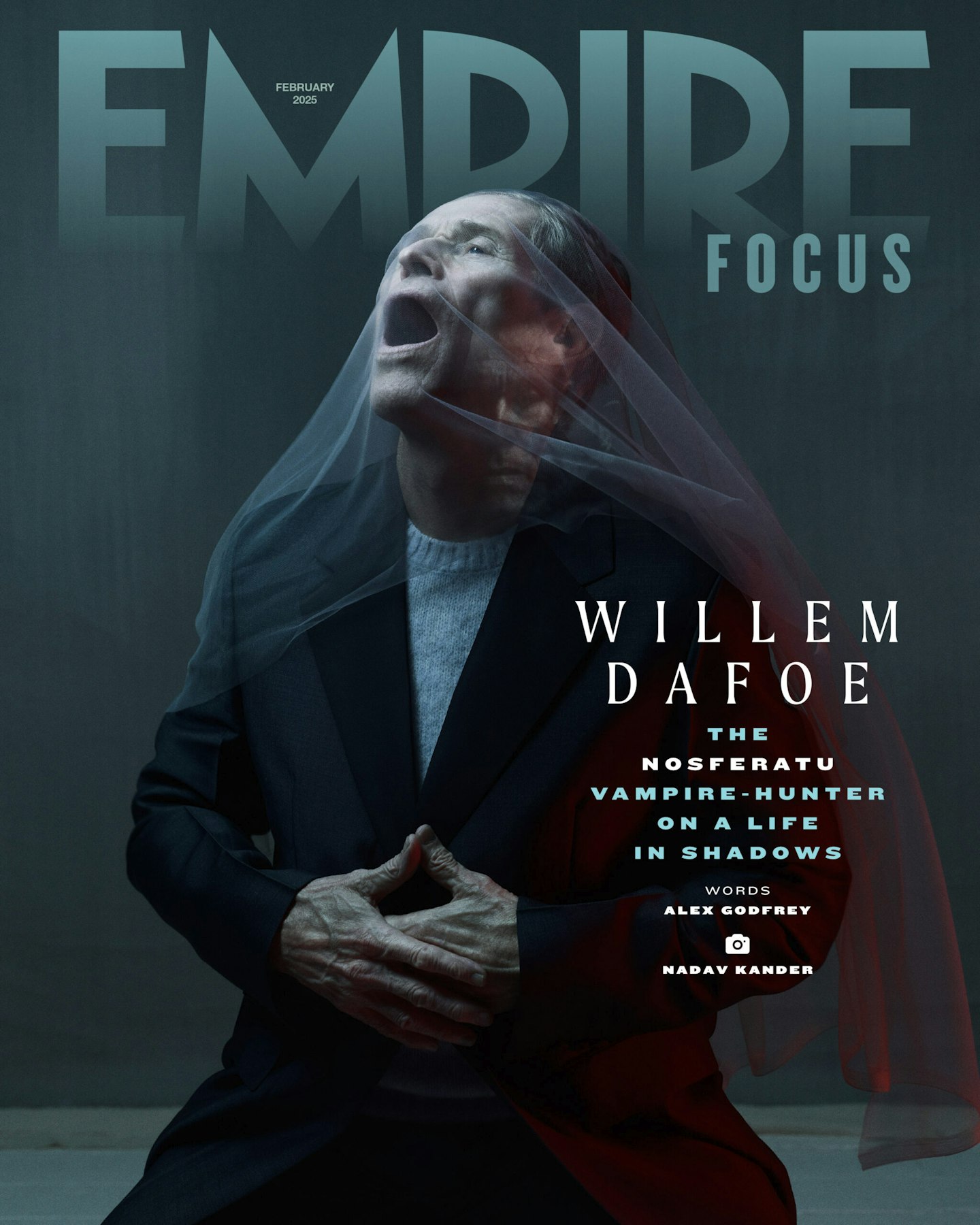

Willem Dafoe is one of the world’s biggest actors — but over five decades on screen, he’s been consistently drawn to oddballs. With his unhinged vampire hunter in Nosferatu about to be unleashed, we speak to him about challenging the norm.

“Chaos reigns,” said the fox.

Lars von Trier’s 2009 drama Antichrist was unforgiving cinema and, as the psychotherapist navigating his wife’s (Charlotte Gainsbourg) overwhelming grief after the death of their young son, Dafoe may have been the only actor capable of taking on its myriad challenges. It made perfect sense that Von Trier would ask him to voice the fox too, uttering those words while eating itself alive.

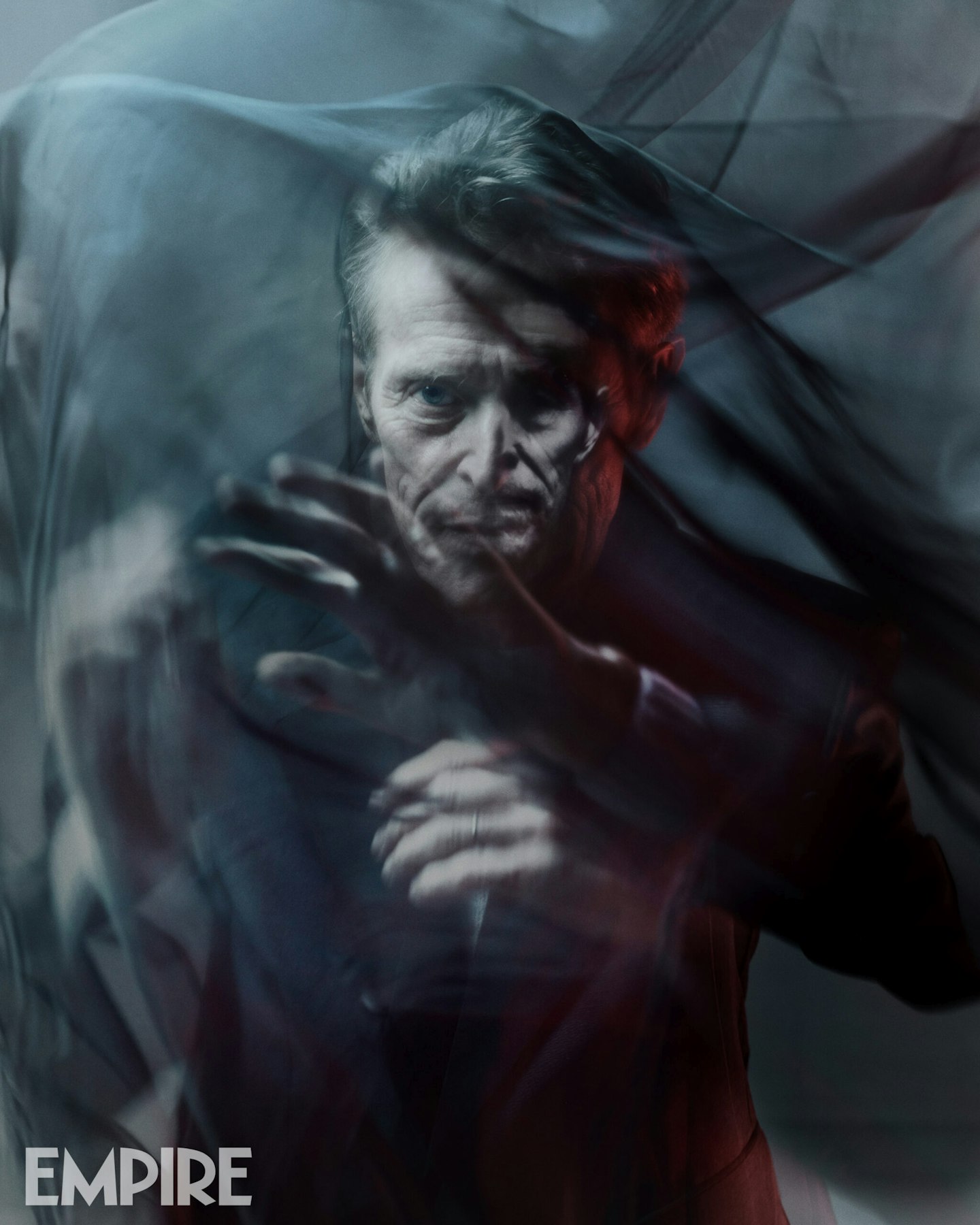

On screen, Dafoe has never been far from chaos. His first film appearance, in 1980, was in Michael Cimino’s notoriously catastrophic Heaven’s Gate; Dafoe was fired for laughing at a joke on set. He was Oscar-nominated for playing Sgt Elias in 1986’s Platoon, for which he and the cast underwent an extreme training process: Oliver Stone’s team of Vietnam vets messed with the cast’s minds and kept them awake by firing guns as they slept in holes they’d dug in the ground themselves. He starred as Jesus in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation Of Christ, released in a swirl of protest, terrorist attacks and death threats. He has played outsiders, crackpots and whack-jobs for those exploring the unorthodox: von Trier, three times, and also David Lynch, Paul Schrader, Yorgos Lanthimos, John Waters, Abel Ferrara and Tim Burton. He’s worked with Robert Eggers three times now too, including the upcoming Nosferatu, in which he stars as vampire hunter Professor von Franz, an occult-obsessed, excommunicated academic who rigidly rejects conservative thinking.

As we discover over a glorious hour with Dafoe, speaking to Empire from a rustic study in his home in Rome, there’s a reason he plays so many people on the fringes and from the underbelly. He is drawn to otherness, fascinated by those who see things differently. Dafoe, though, throughout our conversation, is ebullient and engaged, discussing his work with a joy that seems to only be getting stronger.

In Nosferatu, Professor von Franz has been laughed out of his university and country, after becoming enthralled by alchemy and mysticism. And ultimately, there must be an extremism to him to even think about trying to thwart Nosferatu. What were your thoughts on his obsession?

Well the key is, Robert [Eggers] started out as an actor. And this is the role Robert would play. So I’m standing in for Robert as I do von Franz, because I think Robert has some interest in the same things that von Franz is interested in, and I do as well, somewhat.

In what way?

I’m interested in the unseen world. I’m interested in the occult. I’m interested in homeopathy. I’m interested in alchemy. So it’s fun to play that kind of character in that period context. But a lot also comes from von Franz’s relationships with the other characters. It’s all in a tangle of attraction, of sacrifice, of romance, of bodies, of science, of tradition. That’s all a swirl. And I like that kind of mix.

Regarding what you were just saying about your own interests and how they overlap-

I mean, I don’t want to over-stress that. [Laughs].

No, but von Franz says we’ve been blinded by science. What are your thoughts on our reliance on science, as opposed to the unknown, the supernatural, the things we can’t comprehend?

Well, listen, I grew up in a medical family, so I’m surrounded by science and logic and mathematics and that sort of thing. But I’ve always been attracted to things that are kind of a contradiction of those things, the illogical, the unseen, the unexplainable. Not obsessively. As I say it, I think, “Wow, that sounds like I’m a real wild guy,” like I’m always contemplating the dark side of things. But... I’ve always been drawn to belief systems and what people are afraid of and what shapes their strategies for living. I’m interested in spiritual impulse, and I think spiritual impulse gets addressed when you start trying to see what is behind what we see, or what we think we see. I think that’s the business of von Franz a little bit. He’s always considering the possibility that there’s something beyond what we understand. That’s a basic sense of wonder and curiosity that I think is necessary to cultivate to have a good life.

"I’m putting myself in these situations where there’s enough of a taste, enough of a reality, that I can really address myself to some fundamental things about pain and grieving."

Von Franz also has some encounters with rats. There were 5,000 of them on set; at one point you're surrounded by them. How was that to deal with?

It was fun. It’s not something you get to do every day, you know? The most difficult thing was you were always worried about stepping on them. But they were very sweet rats, and I wasn’t worried about getting bitten. It was quite difficult to keep them all in one place and keep them from scurrying off set. They aren’t natural actors. They’ve got better things to do, like... eat things, you know? And burrow. [Laughs]

In 2000’s Shadow Of The Vampire you played Nosferatu, of sorts – certainly the actor who played him, Max Schreck. Eddie Izzard’s character explains that Schreck is a character actor, and that “as part of his preparation, he submerges his own personality in the character he’s playing.” He says, “He went to Czechoslovakia weeks ago to absorb the flavour of the place.” On The Lighthouse, during filming you stayed in a fisherman’s cottage on your own and submerged yourself in that environment. So do you see yourself like that?

I don’t quite recognise that, because I think you gotta have some idea of what the character is to surrender yourself to the situation, and then the situation makes the character emerge. Method actors want to be called by their character’s name, or they will only wear things that they wear in the movie, to smear the line between being on camera and their life while they’re making it. I’m not really like that at all. I like to hang out on the set, and I like to prepare. I like to practise at doing things that my character does. But I think I’m activated by the camera. And when we create a frame, then I enter into it.

But you chose to stay in that little cottage on The Lighthouse while everyone else was fraternising in a hotel with their mod cons.

Just because I can concentrate better. Am I [The Lighthouse’s] Thomas Wake when I’m at home [there]? No, but I love waking up early to practise, and making a little fire in the potbelly stove. And I like looking out and checking the weather. They’re all things that help me be there when I have to be there. It’s not rigid. I don’t try to close out other things. But every time you go on location, you’re taken away from your routine, and particularly if you’re by yourself, which I usually am, you have an opportunity to live a different way. And it usually makes sense to have that coloured somewhat by what your character is. And if you have a particular profession or skill that you’re practicing for the movie, it’s natural that in your time there, you deal with that. So I guess I’m trying to tell you that I don’t quite relate to this thing of staying in character.

Which I’m sure you didn’t do for the next Robert Eggers film you did, The Northman, in which your character Heimir, a jester, is killed and ends up as a little, dead, mummified head.

Yeah, that’s beautiful. [Laughs]

What was your first thought when you saw that? Because it does look exactly like you and it’s an exquisite, unsettling thing.

Well, that was part of the enticement. I mean, I knew that there was going to be that little head, and... you know, it’s nice to have a good entrance and a good exit.

Yes, many of your characters have died in extraordinary ways. Would you oblige me if I list some of them?

Sure, do it.

The Northman, then: decapitated, mummified. The Lighthouse, you’re smashed in the head with an axe, but also buried alive before that. Platoon, you’re shot to bits. Wild At Heart, you shotgun your own head to bits. Shadow Of The Vampire, you sort of spontaneously-

Burn.

Pasolini, you are run over repeatedly with your own car. And lest we forget [in The Last Temptation Of Christ], crucifixion.

Yes. But did I die…? [Laughs]

I guess that’s a matter of perspective. Do you get a kick out of seeing yourself die in different ways?

I do. Because... it raises the stakes. Everyone, unless they’re asleep, has an imagination about their death. So when you’re in a little fiction, getting to play out this kind of fantasy of imagining a version of what could happen to you, even in these extreme cases, something about that experience is elevated. It’s not normal. It’s very specific and it’s personal, but it’s not you, because the circumstances are not of your life. So that’s where you’re really able to tap into that childlike imagination of playing cops and robbers. Because you have a stake, and some kind of understanding of the fear, the drama of dying. And you’ve thought about it, somehow. So then to enact it, even without any real risk or any real reality, is a beautiful exercise. I’m sure somewhere there are some rituals in various cultures where it’s done to help people prepare for their death.

Clearly you’re drawn to the unconventional. You were made to leave high school for producing a documentary segment for which you interviewed three students who were all outsiders: a drug dealer, a Satan worshiper and a nudist. So it seems you’ve always been interested in people on the fringes, and you’ve played them a lot. Do you agree?

I do. I do. Because they’re not me, and they also give us a different perspective, because if you’re functioning in society, you’re ruled by the rules of society. And some people, through circumstances or tragedy or lack of something, are forced outside of that, but the result is they have a different perspective. And those are the people that can say, “Oh, the emperor is not wearing any clothes.” It takes the people that aren’t ruled by the agreement of the majority to let us see. Because, if you have any ambition, and particularly if you’re living in a materialist, capitalist culture, it’s all about accumulation, it’s all about getting ahead in the world, it’s about comfort, it’s about keeping the wolf from the door. So when you address people that don’t have that luxury of that kind of comfort, sometimes they can really make you see the reality of things better than you can, because you’ve been coddled. So it’s a little bit of an experiment. You can say, “Well, that’s just romantic,” but something about that kind of romance and imagination about those things gets me going. Makes me see new possibilities.

"We don’t watch a performance because it’s like life. We watch a performance because something very particular and very special is happening."

You seek out directors that explore such material too. You’ve worked with Lars von Trier three times. Most notably on Antichrist, which is a major and very moving piece of work.

I think it’s a really good movie. It really kicks the hornets’ nest and talks about some things that are very difficult to speak about. If you’re not too bright, you can misidentify it, but it’s really interesting about the way it talks about logic and illogic and emotion and grief and women’s powers and men’s fear of women, and sexuality... There’s a whole stew there that I think is really well addressed.

When you took that on, and absorbed what it was exploring and how powerful it could be, how did you size that up?

It goes back to what we were talking about before. It’s all pretend. I’m putting myself in these situations where there’s enough of a taste, enough of a reality, that I can really address myself to some fundamental things about pain and grieving. And, I never know what things mean, but I know what interests me. I know what calls me. And some of the things in that [film] are very evocative and draw me into them. Also just the preparation: in the movie I’m a particular kind of therapist, and I went to Columbia University to work with the people that were doing Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, which is a therapy that Lars knew quite well. So I was learning a different way to problem-solve and a different way of thinking. That really engaged me, the whole training of the mind and controlling of your emotions.

Lars was extremely depressed when he wrote and made the film. The shoot itself was tenuous, as he was on the brink, some days, of being uncapable of being on set. What was it like to navigate that?

It was a small cast, and we were in quite a remote place, and he was quite delicate. Very committed, but very delicate. We’d have dinner, and he’d say, “Listen, I may not be there tomorrow. I will be directing by remote, from the trailer.” And he’d say that almost every day, but he was always there. So yeah, it was tenuous [laughs], but after a little while, you realised that he just needed to say that in order to go on. So that kind of tension can be nerve-racking, but if you’re engaged, it also can be beautiful, because you don’t think about yesterday, you don’t think about tomorrow, you’re very much involved in what you’re doing. That kind of concentration is what makes the difference between a good or bad performance. I’ve been doing this long enough that maybe I have some craft, some things that I can lean on, but a movie like Antichrist, you’re a little bit in freefall. But if you feel safe in freefall, and if you trust your partners in freefall, that can be very exhilarating.

At what point did he ask you to voice the fox as well? “Chaos reigns” is an iconic line…

[Laughs] He had me voice the fox, but then, knowing him, he probably voiced it himself after, and he didn’t tell me.

David Lynch’s Wild At Heart feels of a piece with what we’ve been discussing. Bobby Peru is scuzzy and sleazy, he’s quite reptilian. You’ve said the dentures were a big part of that.

Yep. Huge. Huge. They were everything. They really made the difference, because they were an obstacle. They made me feel different. They transformed me. I’m telling you, you could be Bobby Peru if I gave you those teeth. You could be a version of Bobby Peru if I gave you those teeth and put them on top of your teeth, and you can close your mouth and you [transforms his mouth and jawline and shows us how to do it]… Just do this. Yeah, relax your jaw a little bit. That puts you in a certain state of mind right there. Don’t you feel something swinging downstairs?

I didn’t expect to be doing a Bobby Peru workshop today.

[Laughs] Well, you know. Might as well. We’re here!

On the subject of things that physically help your performance, let’s discuss your Norman Osborn in the Spider-Man films – a particularly unhinged human being. In 2002’s Spider-Man, the Green Goblin costume left something to be desired, not least because it concealed your face. And then for 2021’s No Way Home it’s like they realised, “Hang on – we’ve got Willem Dafoe. We don’t need a mask.” How do you feel about that?

It was just a pleasure to return to that character. Just like the original, I like the fact that within a scene it could careen from being goofy comedy to drama to action. It has a lot of tricks up its sleeve. And it was a double role. Everybody concentrates on the Green Goblin, but that’s mostly action stuff. I like doing that, and I think I can do it gracefully. But the real meat in the first one is the guy without the mask, Norman Osborn. Those are the meaty scenes. So when people complain about the mask, it’s like, “Come on.” The role is Norman. And then in [No Way Home], we have a little bit more Norman, because part of the game is, you don’t know how much of the Green Goblin is back and how much it’s Norman. That’s the whole play.

To go back again to what you’ve always been drawn to… you’ve said that your earliest film memories were watching the Frankenstein and Dracula reels that your father brought back from work trips to Chicago.

I think that’s true.

Well, after playing Nosferatu in Shadow Of The Vampire and more recently Godwin Baxter in Poor Things, in which you arguably play a Dr Frankenstein type, you’ve sort of played both Frankenstein and Dracula now. There’s a cosmic symmetry there, regarding the seeds that get planted and how they inform who we become later on.

Have at it. I think that’s fair. That’s fair. That’s a case of kind of answering your own question, and all I can say is: Yup!

Okay.

No, I like it. Don’t get me wrong. I like it.

Yorgos Lanthimos said – no, sorry, actually you said this-

You’re confusing what Yorgos says with what I say? He’d be appalled! [Laughs]

You said that on Poor Things, you did a take and he said, “Oh, you’ve done a Willem.” And he asked you to do it again and not do that. Did you recognise what he meant?

Yes. I think he gives me more credit than I deserve about what kind of ability I have as an actor. He’s kind of allergic to a certain kind of acting. He’s allergic to acting, period. He doesn’t want you to act. So anytime he feels something kind of crafted… the point is, he says you’re leaning on something that isn’t pure enough for this character. At least, that’s my interpretation. I had to... take the hot sauce off a little. Hold the hot sauce!

On that… I read an interview with you from 1987, in which you said, “A performance is like a life that I flail angrily through until it’s over.” Do you still feel like that?

Sometimes I do. Yes. I mean, you have to make contact. It’s gotta be elevated. We don’t watch a performance because it’s like life. We watch a performance because something very particular and very special is happening. It shouldn’t remind us necessarily of our life. It shouldn’t necessarily remind us of our feelings. It should be beyond that. At its best, it should make us think, “Wow, I never thought like that,” or, “I never imagined that.” That’s when a performance turns me on. And it’s not about size or melodrama or transgression. Some of my favourite actors when I was a kid were very laid-back, non-histrionic actors like Warren Oates or Harry Dean Stanton. 1987, wow. I’m a different person now, but that sounds okay. I don’t mind being tagged by that.

This article first appeared in the February 2025 issue of Empire. Photography by Nadav Kander, shot exclusively for Empire in London.

Nosferatu is in UK cinemas from 1 January.