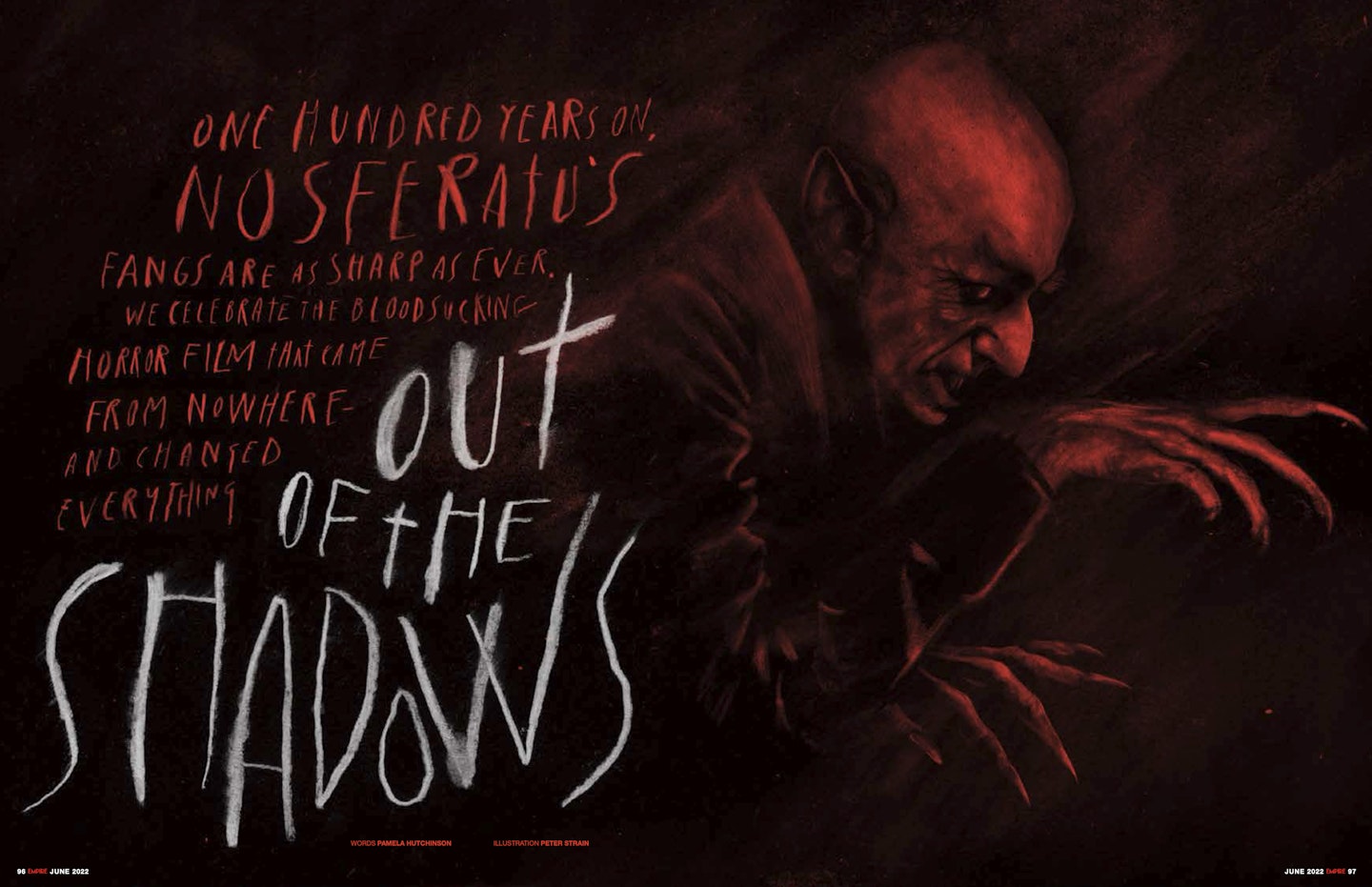

Over one hundred years on, Nosferatu’s fangs are as sharp as ever. Empire celebrates the bloodsucking horror film that came from nowhere – and changed everything.

“Wanted: 30 – 50 rats.”

This advert, placed in a local German newspaper in the summer of 1921, heralded the production of a film that continues to haunt our screens, and our imaginations. F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony Of Horror was the first and is arguably still the best vampire movie. Its influence is so vast, it is almost impossible to measure. It is as timely now as when it was made, in the wake of another devastating pandemic.

“It’s kind of the invention of the modern horror movie,” Robert Eggers tells Empire — the director of The Northman and The Lighthouse had long cherished a plan for his own Nosferatu remake. “The thing that really makes it so memorable and important for everyone is Max Schreck,” he says of the original. “His performance, and the make-up, which he did himself, is the blood of Nosferatu. It is completely magical.”

Schreck was the enigmatic lead actor with the amazing prosthetics who played the vampire, Count Orlok. Little is known about the man, whose short career was primarily spent on stage; the biggest myth swirling around Nosferatu is that Schreck was a vampire himself. How else to explain his creepy appearance and unsettling name? Schreck is German for “terror”.

The plot of Nosferatu may be familiar, given it began life as an uncredited, bootleg adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula. In fact, Stoker’s widow Florence would later sue the filmmakers and demand that the film be destroyed. Nosferatu had been judged “too horrible” for distribution in Britain, but Florence ensured that the one copy that had been shown privately here was burned before anyone else could see it. For years, then, the movie, like its unearthly villain, was considered undead, existing only because a few rare copies escaped the axe. Yet by the 1960s there were enough prints in circulation for it to become an early cult film, and today it is widely available in a restoration that is as close as possible to the original. Even the original score, which was lost for years, has been found and re-recorded.

“When I first watched Nosferatu, it was a black-and-white VHS,” says Eggers of discovering the film. “We didn’t have the Blu-ray, the version that the Murnau estate has now restored in all its glory. But in some ways, that VHS version had even more atmosphere, because the print it was made from was such poor quality that you couldn’t see the seams in Max Schreck’s make-up. His eyes looked cat-like, and there was a kind of sfumato [a hazy blur] over the whole image. As a kid... I’d never seen anything like it.” There is still nothing quite like it.

***

Robert Eggers is not wrong about Orlok: his grisly face and terrifying silhouette, as his shadow inches towards his victims, are unforgettable. He moves strangely, gliding across a ship’s deck or rising uncannily from his bedtime coffin without a lurch, as if pivoting impossibly on his heels. When he pauses in a narrow doorway, the gothic arch frames him as tightly as that coffin. But he wasn’t all Schreck’s invention.

Orlok’s true creator was Albin Grau, Nosferatu’s producer and art director. He had fought during World War I, and while on the Serbian front heard a story of how the spectre of a local farmer stalked a nearby village. When his coffin was cracked open, the body was intact, but his teeth had grown excessively long, protruding right out of his mouth. To save the man’s soul, villagers plunged a wooden stake through his heart while saying prayers.

The image of this Serbian vampire preoccupied Grau, and in a 1921 essay he would describe the war, and the fear that it spread through Europe, as a “monstrous event that is unleashed across the earth like a cosmic vampire to drink the blood of millions and millions of men”. When Grau started work on Nosferatu he drew a picture of a vampire with extended front teeth and beams of light shooting from his eyes; a hunched creature which looked more like a winged armadillo than a man.

“Orlok is the Patient Zero of vampires" – Anna Bogutskaya

Grau had a long-standing interest in the occult, but the myth of the vampire also represented a country battle-scarred and economically weakened by losing the war, in mourning for its fallen soldiers, and reeling from the 1918-1920 flu pandemic. Many people in Germany, including Grau, turned to the supernatural for answers. You can see that influence in many of the great German films of the period, such as The Cabinet Of Dr Caligari (1920), with its sleepwalking murderer, Der Golem (1920), which was inspired by a Jewish folk legend, and of course Nosferatu.

Grau’s chosen director, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, also had an interest in the occult, and had also fought in the war. He saw heavy action as a fighter pilot, surviving eight serious crashes, and his close friend, the writer Hans Ehrenbaum- Degele (also believed to be his lover), died in action in 1915. Demobbed in 1919, Murnau moved into the film industry and worked intensely, directing nine features in three years, before Grau approached him for Nosferatu.

Filming began in July 1921, with a budget so tight they could afford only a single camera. The German scenes were shot mostly in the port city of Wismar, and the Transylvanian sequences were filmed in northern Slovakia; Orlok’s home, Orava Castle, is open to the public should you care to visit. Murnau’s direction departs from the theatrical Expressionist style of the time to tease the terror out of its mostly rural locations, creating frames that mimic classic German Romantic art.

“People think of Nosferatu as a German Expressionist film,” says Eggers, “but they were trying to do a more photo-realistic version of Biedermeier Germany and the Romantic tradition. You can see that the costumes, the props and the set-dressing endeavoured to be very period-correct for 1838.”

For the supernatural aspects, Murnau deployed simple effects such as fast motion (undercranking the camera) and negative film to conjure the uncanny — camera tricks that triumph because of their simplicity. Light is everything in this movie and Nosferatu’s greatest gift to vampire lore is the ubiquitous trope of demise by sunlight. “The death of Dracula in the book is actually quite boring,” says Dr Cristina Massaccesi, associate professor at University College London, and author of the book Nosferatu: A Symphony Of Horror. “He’s stabbed and it’s just like a normal villain being dispatched. But the film has this incredible supernatural element to the vampire being killed by sunlight, because he really is a creature of the night.”

That is not the film’s only deviation from Dracula. Grau’s screenwriter Henrik Galeen changed the names (Dracula becomes Orlok), and altered the setting, from late Victorian Whitby to 1838 (the year of a plague outbreak in Bremen) and the fictional city of Wisborg. There, a man named Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim), working for a sinister estate agent called Knock (Alexander Granach), is sent to Transylvania to meet Orlok, who wants to buy a house in Wisborg. Hutter wakes up in Orlok’s castle the next morning with puncture wounds in his neck. And then, Nosferatu really comes into its own.

***

The screenplay reads like a spooky poem: “Yet in the sand... something moves violently... something is alive... jumps out... horrible animals... rats!!” Those rats emerge from coffins transported by Orlok from Transylvania to Wisborg, coffins that are, according to one of the film’s captions, “filled with accursed earth from the field of Black Death.” These rats spread disease just as Orlok, “the bird of death”, kills his victims — by biting. Although Orlok cannot create new vampires, a miasma of death surrounds him that’s as contagious as a pandemic. The crew on Orlok’s ship die off one by one. By the time Orlok disembarks from a ghost ship, carrying his own coffin as he wanders the deserted streets, the city of Wisborg is fully stricken by plague and panic. Crosses are chalked on doors, and townsfolk chase the deranged Knock, clearly under Orlok’s thrall, out of town.

“Orlok is the Patient Zero of vampires,” says Anna Bogutskaya, writer, broadcaster and host of the Final Girls horror podcast. “He is a source of a plague that is unstoppable.” Orlok is a beast who cannot pass for human. He has long, pointed ears covered in tufts of hair; sharp, blade-like teeth that force his mouth permanently open; and a hunched back. His long, talon-like nails grow longer and more gnarled over the course of the film — just like the Serbian vampire in his coffin.

“What I really enjoyed about Nosferatu was the loneliness of the character” – Claes Bang

Bogutskaya compares Orlok to a cockroach scuttling into the bedroom of Hutter’s wife, Ellen (Greta Schröder); Grau said the inspiration for Orlok’s appearance came from watching a spider feed on its prey. For Professor Stacey Abbott of the University of Roehampton, and the author of the book Celluloid Vampires, Orlok’s grim appearance is another important part of the film’s influence. “We keep coming back to those moments where the vampire is really monstrous, and it kind of spills out of them,” she says. “There’s a great line in Buffy The Vampire Slayer where they refer to the Master, who I would say is in a direct line from Orlok. They say he has moved beyond the need to look human, and he is just pure vampire.”

Orlok represents the elusive terror of diseased breath. He can pass through walls, and lives in the dark. The danger is airborne. “It feels incredibly relevant,” says Abbott. “The film came out in the wake of the Spanish flu epidemic, so it has these very overt connections to pestilence and disease and plague.” The word “nosferatu” itself appeared in Bram Stoker’s novel. It is thought to be an old Romanian or Slavic word for “vampire” or “undead”, but its root may well be the Greek “nosphorus”, meaning “plague-carrier”. There are connections to plagues in ancient vampire folklore — the undead carry disease when they rise from their graves.

The most famous and influential shots in the film are of Orlok’s warped shadow gliding up the staircase towards Ellen’s bedroom and falling across her body in bed. You can’t resist the power of this darkness, a danger you might have accidentally invited into your home — like a vampire or a disease.

And so this ghoulish film has spread a widening influence across cinema. Orlok isn’t just a figure of horror, but also of terrible sadness. He is shown framed in the window of his new Wisborg home gazing listlessly across the street to Ellen’s house. His eyes are doleful, and he has to turn away because the pain of longing is unbearable.

“What I really enjoyed about Nosferatu was the loneliness of the character,” says Claes Bang, who played the title character in the BBC’s 2020 take on Dracula. “You’ve been alive for 200 years now, you haven’t spoken to anybody in 50, it’s a Tuesday afternoon in November, it’s about to get dark and you’re just about to get out of your coffin — but why bother? There’s no-one there, and there’s no-one to feed on... I’m making a bit of a joke out of it, but living forever and having nothing to do and no-one to share it with must be so weird. That loneliness and weirdness came out really well in Nosferatu.”

Perhaps this is why the film has aged so well: our hearts still break a little at this image of a monster driven mad by immortality.

***

Werner Herzog certainly channelled the world-weary sorrow of eternal life when he remade the film as Nosferatu The Vampyre in 1979, with Klaus Kinski as the isolated Count. Herzog’s Dracula (the name was changed back again) is a more sympathetic figure, and his production was more ambitious — for one scene in the film he insisted on releasing not 30 or 50 rats, but 11,000.

One of the most interesting riffs on Nosferatu is E. Elias Merhige’s 2000 film Shadow Of The Vampire, which runs with the idea that Max Schreck really was a bloodsucker. Willem Dafoe stars as an ageing, embittered Schreck, coaxed into performing for the camera. It’s a chilling film, which channels the eerie experience of watching Nosferatu into a gruesome creation myth. And it was made with reverence.

“To play Max Schreck, I had this beautiful model of him in Nosferatu,” Dafoe tells Empire of his preparation. “I watched it a lot. It’s animalistic, and planted a seed for a whole vampire mythology. Visually, it’s very striking and plays on your imagination. Murnau was an incredible filmmaker. That was my guide, my place to start. The truth is, you can never really copy.”

The legacy continues to spread. “We’re still seeing Nosferatu in every single vampire movie that’s been made since 1999,” says Bogutskaya. It’s hard to think of a vampire who isn’t destroyed by rays of sunlight, or whose shadow doesn’t fall across his victim before he bites. Eggers compares the cross-editing in the climax of Nosferatu to that in the films of Francis Ford Coppola — especially, of course, his lurid Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

“There is a bit of Nosferatu in a lot of vampire films,” agrees Massaccesi. And in television too: there are traces of Orlok in the Stephen King adaptation Salem’s Lot, while American Horror Story: Hotel explores the idea that Schreck infected Murnau with vampirism. He then, the show posits, bit Rudolph Valentino when he came to Hollywood, the plague carrying to Tinseltown just as the influence of Nosferatu spread to American cinema.

Having embodied the mysterious figure at the heart of the film, Dafoe nails the reasons why Nosferatu endures. “So much of that has to do with the thing about the undead, and desire, sexuality, sleep... There are so many things floating around in there. Essential themes about the stories we tell. And the historical context makes it romantic and mysterious and plays on our imagination.”

A century after it was first released, Nosferatu continues to evoke our deepest fears, as proven by how often we catch glimpses of it in our favourite horror movies. It represents an infection in the very blood of cinema, one that cannot be contained. Not until the lights come up in the cinema, the rats scurry away and the vampire is banished once more — but never for good.

This feature first appeared in the July 2022 issue of Empire.