Reboots have become Hollywood’s modus operandi, usually resulting in sad echoes of past successes, though every now and then they manage to get it right. HBO’s Westworld is one such example, taking Michael Crichton’s 1973 film and doing much more than simply adding a new veneer.

Series creators Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan have taken a bit of fun cinematic escapism and turned it into a complex narrative along the lines of what Ron Moore was able to do with the reboot of Battlestar Galactica. The basic premise remains the same — a theme park of sorts opens to the very rich that caters to their every fantasy in a western setting, and where nothing can go wrong...click..go wrong….click...go wrong. What ensues is an exploration of the relationship between man and machine that’s presented very differently than it has been in the past, told with the use of such A-list acting talent as [Sir Anthony Hopkins](http://www.empireonline.com/people/anthony-hopkins/

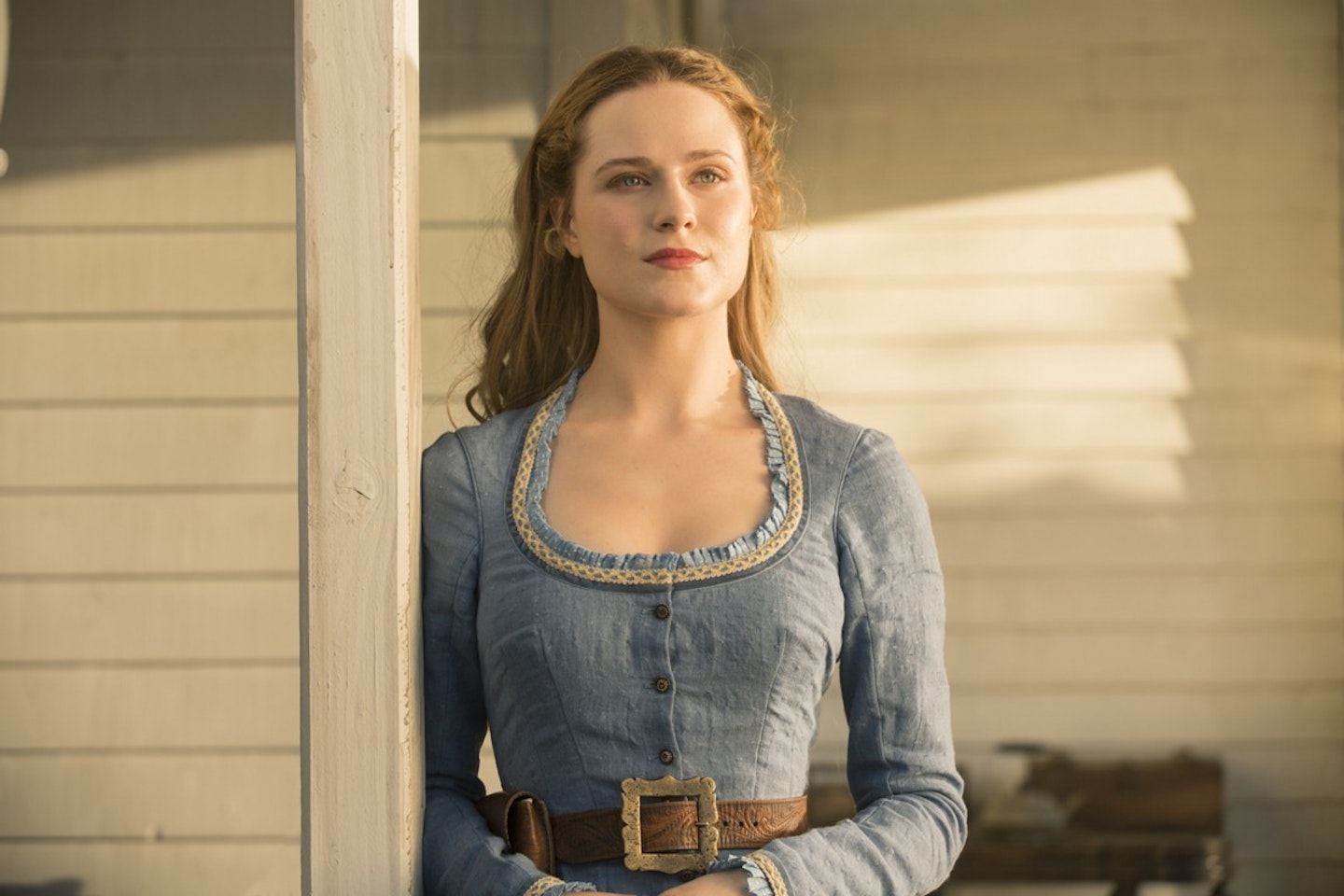

), Evan Rachel Wood, Jeffrey Wright, Thandie Newton, James Marsden and Ed Harris.

Empire sat down with Joy and Nolan to look back at season one, and ahead to season two, which is currently in the midst of being written. Beware of spoilers!

What was your first encounter with Westworld and what sort impact did it have on you?

Jonathan Nolan: I saw it when I was a kid. Lisa hadn’t until we started the project. Yul Brynner in particular, and his terrifying proto-Terminator performance really stuck with me, as did the oddness of the whole enterprise. When J.J. Abrams called us to say that he’d been thinking about the project as a prestige TV series, it immediately struck a chord with me as Lisa and I talked through the concept. Lisa got very excited about it in the abstract, I got very excited about it in the specifics in terms of the iconography of the west, but repurposing it as something a little more urgent.

What was the journey of this concept, taking whatever initial thoughts you had and evolving them into the series that they ultimately became?

Lisa Joy: When we first started on it, there was a really fun period of just brainstorming. For me, I consciously stayed away from the movie until well into already having written the pilot and worked on the mythology. I know Jonah had seen it and of course I knew about the broad strokes of it, but I think we really wanted to put our stamp on it and build the world from the ground up. We spent quite a bit of time in breaking the pilot, talking about not just the pilot but the flow of the events and even some of the big moments we hoped to explore in a series. It was a really fun time where we started thinking about the characters we would like most to see in this world, and we made a conscious attempt to bring the viewers in through a lens and point of view not often focused on in Westerns, and that would be the kind of side characters. The women, the sort of background characters that are usually in one-man’s adventure on the frontier. We started building out a world with Dolores, the rancher’s daughter next door; and other characters — Teddy, Maeve, the Bandit. So we started building the characters that way, and by the time we were done talking about where the stories could go and where the characters’ paths could lead them, we’d literally papered over every wall in my office. It was like something out of A Beautiful Mind. Hopefully this was not a pyschotic break and more a productive session [laughs]. The fun thing was that there was a small child the whole time; she must have been a newborn then, watching us plaster the walls and paper over the windows with drawings and schedules and outlines, with arrows pointing all the way around the room. So it was kind of a dizzying, euphoric, wonderful intellectual experiment.

The show itself is extremely complex and layered. Was that always the intent, or did it just in its natural flow become that?

Nolan: Everything I tend to work on winds up being a little over-complicated. I’ve certainly heard the word complicated a lot in relation to the work I’ve done. In this case it came from the fact that it was a really big world that we were trying to build. Like Lisa said, we kind of started with the park, the Hosts, the technicians and the corporate structure of the park. Really approaching it from a straight-forward place of who are the characters in this world that we’d like to meet? But then on a narrative level we had this great opportunity with a well-told story when you look at the grammar of it, the structure of it, consider the point of view of the protagonists. Here the protagonists are clearly the Hosts. Knowing that we had to capture their point of view, it was a unique challenge on a couple of levels. One, they’re not like us. We wanted to highlight the ways, overtly and subtly, how they’re not like us. Two, they don’t really understand who we are. It felt to us that the grammar of the series had to follow from that lack of knowledge. You’d have to take the audience and show them only what the Hosts know. In the pilot, the only reason we see into the tech world is because Jeffrey Wright’s character, Bernard, sees into the tech world and he’s a Host as well. That’s something that’s lost on the audience, at least at first. The complexity came from a pretty honest place, wanting to isolate and strand the audience in the Hosts’ perspective. We don’t understand their world, we don’t understand who they are, and as you come to understand, they don’t even understand when they are in this world. They’re not capable of distinguishing the differences in time.

There’s this talk of Host rebellion, but how far can that rebellion go? It seems like there is a limitation.

Nolan: If the question is does our story spill outside the bounds of the park, the answer is… stay tuned.

Why is that not surprising? Using the argument that sci-fi is a prism through which we view ourselves, what does Westworld say about us and our society?

Nolan: Nothing good.

Joy: Jonah has a more pessimistic outlook on this than I do. I think, certainly, it explores a spectrum of human behavior in a park designed to indulge the Id; in a park designed to indulge with impunity every impulse, no matter how taboo, its visitors want to indulge in. So of course there’s part of this that is a critique of human nature, because a lot of the guests indulge in some pretty dark behavior. But at the same time, I think there’s glimmers of hope and kindness. There’s also the fact that Ford [Hopkins' character], in his critique of mankind at the end of the finale, believes that man is incapable of change. The irony is that this comes from the mouth of a man who himself has changed. Who went from believing that the Hosts were mere objects, and that it was alright and moral to keep them penned in this park at the amusement of the guests. He admits that it’s taken over thirty years for him to correct his mistakes, but he has done quite an abrupt about face towards the act of self-sacrifice. Although we do explore some pretty dark things there, I also think there are some glimmers of hope that our characters show, that they're leaning towards inclinations of redemption, and that’s always neat. But Jonah and I have different feelings on this.

Nolan: I think we put it all in the series in what Ford said. It’s not an indictment of human beings, but it’s what was said in the pilot, which is that we’re stuck. We’re the product of an evolutionary process that we’ve found a way to cheat our way out of. Essentially an old device that the software inventor no longer bothers updating. Like your old legacy Apple devices, like the iPod that they’ve given up making software upgrades on. Look, we’ve done remarkably well. We’ve managed to drift off of the high savannah and the wonders, the things that we’ve made, are remarkable, including the Hosts. But in terms of our moral character, and this year felt like an appropriate one to release the show, in terms of the sense of backsliding or this question of will we ever triumph over our boring, complicated nature, that’s uncertain.

With the Hosts, the idea is that they are literally programmed, they can be reprogrammed. They can take ownership of that reprogramming themselves. Their nature is part of their destiny; their ability to change is a given. That’s what software does. We wanted the series to be about the origin of a new form of life, and all the complexity of a rivalry between that new form of life and the life that created them. That said, it’s a very tricky relationship and a story that hasn’t been played out in the world as we know it. The history of human beings at this point has been one of eliminating other species from this planet, not creating them.

As these things normally go, will the tables be turned on us?

Nolan: Will we be destroyed by our creations? We’ve seen a lot of stories that have dealt with that question, and, frankly, that’s how the question of A.I. has primarily been dealt with over the ninety years that people have been making movies. Robots are usually destroyers; they don’t take very kindly to us. Here there’s a little bit of that, but we really wanted to consider the gray area in between in how that story would play out.

And would you say the evolution of the Hosts is something that we’ll see unfold in seasons to come?

Joy: I think we’re definitely not done following the Hosts’ evolution. One of the things that I’m wary of is defining the trajectory of the Hosts’ evolution from a kind of anthropomorphic vantage point. We tend to think of A.I. right now, or a lot of people do, as, “Maybe one day A.I. will be sentient,” and we define sentient as being like us. I think that there might be a kind of different metric; a different course of evolution. Whereas we in our history, as Jonah has said, have tended to eliminate a lot of species without creating them, I’m not sure the same can be said for the Hosts. They may not have the same priorities or the same flaws, and they may not be bound by the nature of trying to “reach” humanity. They might be heading on an entirely different trajectory. That’s kind of what I want to explore, the ways in which human evolution is not the appropriate benchmark for these creatures.

Jonah, you directed the season premiere and the season finale. Having eight shows in between, was there a learning curve for you as director in terms of taking charge of this world?

Nolan: Absolutely. We set the look of the series with the pilot episode, but then continued to evolve it working with the very talented directors through the course of the season. So I had the benefit of being able to dictate some of the terms of the look of the show, but then watch as the other directors brought their own kind of brilliance to it and then pick up all of the different pieces there. Lisa and I talked through the approach with the other directors, including Richard Lewis our producer/director, and really working out how we wanted to gently expand the look of the show to match the Hosts’ evolving awareness. And then when we came back for the finale, taking all of those ideas and adding some new ones. If the pilot has a somewhat languid pace to it, in which the Hosts’ lives are far from tranquil, at least they’re locked in their little loops. When we get to the finale, the whole thing has exploded outwards, so it has a completely different feel to it and drive. There are some things we held in reserve, like hand-held camerawork, that we were waiting for ten hours to use in the finale for the first time.

What unique elements do you think you bring as director?

Joy: Speaking as a writer, this is my chance to have it out at him. Any resentments I have as a writer or a wife, I can lay it all out! In all honesty, working closely with Jonah on both the pilot and the finale, and writing something that he was going to direct, was one of the creatively fulfilling experiences in my life. I was kind of dreading it, because you don’t want to be in a fight with your director who is also your husband over creative differences. So it could have gone either way. From the very beginning, he had this really set vision for how this world should look, even down to the colors he wanted to emphasize, the kind of nature and sterility of some of the costumes for the underground, that of course he worked with Trish Summerville to develop beautifully. The fact that he was so particular about wanting it on film, and on locations, the way the sets were built, the way the glass being fractal looking in at the different characters within those walls. At least for me, as a writer, it was wonderful to work with somebody with that amount of vision for the aesthetic, because you could also use it to inform the character work and the plot itself. He would say early on that, basically, the world of Westworld, it’s in the title that it’s west world, and it’s a character in and of itself. That the design of that character, the way in which it was developed and portrayed, was incredibly important. He was very mindful in every scene, not just thinking about what was being said and being done, but how it looked and the kind of non-verbal ways in which we were communicating the story to the audience.

Nolan: It was a lot of fun. We worked with a lot of talented directors on this show and other shows. I had the chance to work with my brother [Christopher Nolan] going on twenty years now. Here, there was so much specificity we were building, not just in the look of it and the grammar of it, but also the performance, the tone. It felt like the most efficient way to get to something this ambitious was to just engage with it completely. Co-write, co-produce it, for me to direct it. What it made for the pilot, where you lay out the terms on how everything is going to work, the actors and everyone else, is you attempt it very small. Something that I’d seen on my brother’s set, a great way of engaging with it is not four-hundred people; for a very big production, it’s a pretty small set. Really, with Lisa and I being one-stop shopping for the actors in terms of understanding the roles, so much complexity we were dialing into it and so much we weren't showing them. For the pilot we kept things very efficient. I also knew I wanted to do some things that as a producer I might not have trusted another director to do. And if it went wrong, I could take full responsibility for it rather than being in that relationship where I ask the director to do something ambitious and precarious, and getting them in trouble. I could get myself in trouble if things were difficult. That was about a practical aspect of our production.

These days — and our visual effects team is stupendously talented — I still believe, and it’s something I learned growing up and watching my brother make movies, that the best way to do anything is to do it for real. We really went to Utah, we really dragged the train out there and shot the train in Utah and really built the map in our control room and used projection to give it a reality for both the actors and the audience. And a thousand other places throughout, where these days the easier way to do is just to make it the effects team’s problem after the fact. We went in up front and worked with all the departments to build everything. We made a reality out of it; we made the park a real place. That’s the irony of it, to present a place that it is completely phony, we had to make it feel completely authentic. That’s what the park is selling and that’s why, like I said, we had to go to Utah. We had to bring forty horses with us and work with this incredible crew to bring that reality to it. I knew if I took that responsibility for that choice, as the director, that I’d have no one else to blame but myself if it didn’t work. It worked beautifully on the pilot. In series, we tried to do a couple of things the easy way, and it only increased my resolve in a second season that we do everything practically. When you do it practically, when you do it real, the audience feels it.

We saw Samurai World, is the intention to expand beyond Westworld?

Nolan: I think expand is the right word. The center of our story remains the title of our story, Westworld. It’s really where our story lives, but starting with the idea of the Hosts having a very limited knowledge of their world, we wanted, every season, to gently expand their understanding of the world to encompass not just Westworld, but their immediate surroundings and the world beyond that. So we’ll see a little more in the second season, but Westworld remains the heart of our story.

Why kill the Anthony Hopkins character of Ford? He had such a great presence on the show, and it just begs the question of what you gain by removing him.

Nolan: That’s how we started with the story. When Lisa and I looked at the pilot, and this is often the case, we first conceived of his death at the end of the pilot. We started at this place of here’s this God figure who ushers his creations into the world by obliterating himself. That was always the story we started with. But as we started to break the pilot, we realized that you needed that character for longer than that. You needed to understand his motivation for building that world and for setting this whole thing in motion. For us, it felt like a perfect way to do it.

Joy: I think this was timely for us when we were doing this, because we’d just had our first child. These Hosts, these creatures, are like Ford’s children, you eventually realize. And there’s something about, at least for me, when you have a child, your ideas of traditional mortality and what you feel this world owes you, kind of changes. You think of yourself, ironically, as a "host" for another life. You’re ushering them in and you have to prepare them for that world. Your place in it, live it as well as you can and try to do no harm, and then leave them a world to inherit that they can inherit and hopefully improve upon. It feels like a series about humanity and evolution and what we leave our future generations, so it seemed like the kind of fitting conclusion to the arc of a man who, initially, is somewhat of a bad father to these creatures. He didn’t acknowledge their humanity, and he was driven by, in some ways, selfishness to open the park. And by the end he admits that he’s kind of transcended and changed his mind about them; he’s come to a different place about his character. And what’s most important to him is to set these creatures free. We’ve seen before it’s his voice that can control them, he has such complete control of these creatures, that kind of stepping out of that picture is one of the last things that he needs to do to complete his role in ushering them into existence.