*This article was first published in Empire Magazine issue #297 (March 2014). Subscribe to Empire today{

PROLOGUE

WES ANDERSON

When you’ve seen all eight of Wes Anderson’s movies, they can’t help but colour your perceptions. The director enters a beautifully furnished room in a Georgian private members’ club wearing a grey herringbone suit, striped shirt, tie and brown leather shoes. In an ideal world there would be a turntable in the corner playing a Kinks single but never mind, he still looks like a Wes Anderson character stepping onto a Wes Anderson set. Like his movies, Anderson is a fusion of contradictory elements. He combines courtly manners with a nebbishy East Coast intensity, neither of which suggest his Texan upbringing. He is 44 but so youthful-looking that Cate Blanchett compared him to Dorian Gray. He’s a pale, skinny aesthete who’s capable, when necessary, of Hawksian derring-do. He is modest about his successes and candid about his mistakes, yet animated by the kind of conviction that persuades studios and movie stars to take risks on improbable endeavours.

Anderson is arguably the most distinctive American director of the last 20 years (legions of imitations and YouTube parodies attest to that), which is a mixed blessing. His detractors see him as a fussy hipster control freak who creates airless dioramas full of implausible figurines. But what kind of control freak crafts screenplays in collaboration with strong-willed writers such as Owen Wilson, Noah Baumbach and Roman Coppola? Or, when he tries animation, forsakes the neatness of CGI for the handmade imperfections of stop-motion? Or is so fun to work with that he’s built an ever-expanding family of regular performers, the newest arrival being Ralph Fiennes, star of The Grand Budapest Hotel?

"I DON'T THINK I'D BE SUITED TO A WIZARD TYPE OF MOVIE...

Anderson resists overarching theories about his work. He insists that his real concern is story and character; all the recurring tropes that get critics and film-school students excited are secondary. “I probably wouldn’t even notice if I rewatched them but if someone tells me I say, ‘Oh yes, you’re right!’ When you watch a movie and you get some kind of meaning that’s not on the surface, I feel like it’s just as well if they didn’t do it on purpose. It’s subconscious. That’s why I don’t like to think thematically. That’s the last thing I want to do.”

For someone who accepts that he’s a specialist taste, Anderson has navigated Hollywood with enviable panache. He always retains final cut. He always gets funding, even if it’s never as much as he’d like. He’s never been compromised by a high-stakes franchise although, he reluctantly reveals, he was once approached about “a wizard type of movie”. “I have a feeling my name doesn’t come up that much in those types of conversations and I don’t think I’d be suited to it.”

Because Anderson does exactly what he wants, even his flops have integrity and the ability to grow on you. “I remember a friend said, ‘It’s going to be ten years before people appreciate [The Life Aquatic],’” he says. “And she was kind of right. They did a screening of it in New York recently and it was a great night. Like The Royal Tenenbaums. We opened it at the New York Film Festival and it was fine, but we screened it again ten years later and I was like, where were these people ten years ago? It was the exact same room but a completely different experience. So I wouldn’t mind only seeing my movies ten years after they come out.”

PART 1

BOTTLE ROCKET

1994/1996

Anderson was 23 when he started filming his debut movie with his University Of Texas classmate Owen Wilson in 1992. It first surfaced as a 13-minute black-and-white short before James L. Brooks agreed to produce a full-length feature. “I think I was the most confident starting a movie when I did that one because I didn’t really understand,” Anderson reflects. “I had a pretty good idea of what I thought I was supposed to be doing.”

Anderson and Wilson spent a year reworking the screenplay under Brooks’ guidance. “We’d written an epic comedy, like 250 pages, when it should be 100 pages at the most,” says Anderson, laughing at his naivety. After calamitous test screenings, he tightened it even further. “When we first screened the movie it really didn’t work and it needed a lot of attention and tinkering to make it a functional movie. I wasn’t really tuned in to the possibility that it wasn’t going to work. From that point on I was.”

A few Andersonisms are already evident in this loping heist caper: the evocative use of montage and slow motion, the formation of an ad hoc family around a quixotic enterprise, and, in James Caan’s Mr. Henry, the dynamic father figure who turns out to be needy, unreliable and in need of some fathering himself. “I have no idea who that character was based on,” says Anderson. “I think it might have been some combination of people from books and movies. Since then I’ve gotten to know a number of different people, movie directors especially, who are [like] that, so maybe that’s a kind of figure I didn’t know then but I’m drawn to in later life.”

Bottle Rocket didn’t take off, but it made Anderson some influential fans, including Martin Scorsese. A year later, Brooks assured him: “We made cult.”

PART 2

RUSHMORE

1998

From the red theatre curtains that divide the movie into chapters to the final dance sequence, set to the Faces’ rueful Ooh La La, Rushmore announced that Anderson had found his voice — one defined by bold contrasts. Rushmore is rooted in Anderson’s own life (it was shot in his old high school in Houston) yet audacious in its use of artifice. It moves like a comedy yet it’s fuelled by grief and depression. It’s never one thing or the other, but it’s close to perfect.

Anderson and Owen Wilson had written a rough treatment for what they called “the school movie” before starting Bottle Rocket but it only crystallised after a meeting with New Line’s Mike De Luca. “Some of the ideas for the movie came out of making something up to tell Mike in that room,” says Anderson. “Then [New Line] didn’t want to do it but Joe Roth at Touchstone did.”

Among other things, Rushmore was a miracle of casting. As thorny overachiever Max Fischer, newcomer Jason Schwartzman cradled a soft centre of pain inside a shell of abrasive precocity. “Jason doesn’t carry the tension that he did when he was playing the character but he was 16, 17 and he was himself already,” says Anderson. “I’d met so many people that age for this part and when you meet someone who’s a grown-up already and he’s smart and funny in his own way, that’s kind of a surprise.”

Bill Murray’s career-rebooting turn as sardonic, melancholy industrialist Herman Blume made him independent cinema’s go-to guy for midlife affluenza in the likes of Sofia Coppola’s Lost In Translation and Jim Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers. “We thought we didn’t have a chance to get Bill,” says Anderson. “We were told we’d never hear anything. But somehow he read the script and he was in and it was a very simple, quick thing. Probably the easiest casting process I’ve had.” Working for scale (Anderson estimates it was just $9,000), Murray was a reassuring presence. “He wants to have some fun on set. He’s good at keeping the morale up, separate from his job as an actor. He’s sort of a cheerleader at the same time. We couldn’t have asked for a better movie star to turn up on day one.” Murray obviously enjoyed himself: he’s appeared in every one of Anderson’s movies since.

PART 3

THE ROYAL TENENBAUMS

2001

Anderson’s stories tend to evolve from the convergence of several different ideas. In the case of his hit movie about a dysfunctional clan, the crucial threads were Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons, Frank Capra’s You Can’t Take It With You, Kaufman and Ferber’s 1920s play The Royal Family and J. D. Salinger’s stories about the Glass family. It takes place in no particular decade and a city that feels more like a New Yorker cartoon than the real thing. “I was trying to make a version of New York but I was specifically trying not to say the words “New York”, for whatever little theory I had,” he says.

The high-powered ensemble cast, including Ben Stiller and Gwyneth Paltrow, was only possible if everybody worked for scale. Without that, says Anderson, “Cancel the movie. It’s never going to happen. Nobody’s going to fund it.” The tight budget meant that getting Gene Hackman to play volatile patriarch Royal Tenenbaum was as hard as getting Murray had been easy.

“He was the only guy I wanted for it and it was particularly written for him,” says Anderson. It took huge persistence even to secure an early meeting with Hackman, which yielded little. “It wasn’t like a great rapport immediately. He said, ‘I don’t like it when someone writes what I think I am.’ And I said, ‘Well, this has nothing to do with you, you’re just the guy we want to play it.’ He was not entirely happy about that.” When the script was finished, Hackman’s agent was keen but the actor said no and refused to meet again. “He wouldn’t talk to me,” says Anderson. “I kept writing letters. I had my brother draw a picture. I wrote him a go-for-broke letter and maybe that helped. Sort of at the last minute he said yes. He’s a challenging person to direct. He doesn’t like to be directed. But he was great and I could feel it very quickly.”

Anderson’s ambition is sky-high here, as he juggles comedy, tragedy and a dozen key characters with a sure hand and enormous empathy. The visual quotations from personal heroes including Welles and Truffaut have a more pragmatic purpose than delighting observant movie buffs. “Usually it’s making something better by stealing something,” he says. “In a way, everything is coming from somewhere, depending on how far back you want to trace it. It’s just where you want to take from along the way.”

PART 4

THE LIFE AQUATIC WITH STEVE ZISSOU

2004

With Murray back once again to play morose Jacques Cousteau surrogate Steve Zissou, this erratic maritime tale of middle-aged frustration cost twice as much as Tenenbaums but performed half as well. Slammed as self-parodic by many previously supportive critics, it was Anderson’s first big disappointment and he has some thoughts as to why.

“If I could visit myself back then and advise myself I’d probably say make it 90 minutes instead of two hours,” he sighs. “I think I’d have made it easier to get into because there’s so many beginnings to this movie. The other thing I would do is I wouldn’t spend the money we spent. It was released as a big movie but there’s no concession to making it a big movie. It does have scale but it’s more like a humungous art movie. Beyond that” — he shrugs helplessly — “it sort of is what it is and people get into it or not.”

PART 5

THE DARJEELING LIMITED & HOTEL CHEVALIER

2007

To write about three bereaved brothers travelling through India by train — the film’s shoot took cast and crew from Jodhpur to Jaisalmer and through the Thar desert — Anderson explored what you might call Method screenwriting. With collaborators Jason Schwartzman and Roman Coppola, who co-scripted, he lived the film in advance, acting out scenes in promising locations. “We went on this voyage of our own, discovering and gathering all sorts of things that made their way into it.”

The deft 13-minute prologue Hotel Chevalier (starring Schwartzman and Natalie Portman) ended up getting more love than the main feature, but Anderson wasn’t always sure what to do with it. “I had reached the point where I thought it was better not to put the short right in front of the movie. This will sound absurd, but I thought it’d be better if people watched the short a day before the movie.” He smiles. “I don’t know how we would have arranged that. Then the studio didn’t want to include it but we screened it to journalists and they wrote enough about it that the studio changed their minds.”

PART 6

FANTASTIC MR. FOX

2009

When George Clooney, who voices Mr. Fox, read the script for Anderson’s first animated feature he said, “I don’t know who you think this movie is for but let’s just do it.” Anderson laughs as he tells the story. “I kind of felt the same way. I didn’t know.” He had secured the rights from Roald Dahl’s estate a decade earlier and his adaptation (co-written with Noah Baumbach) expands the book’s subversive streak. It’s a strange kind of children’s movie that includes smoking, swearing and a marriage in peril, not to mention moments of oblique poetry and niche comedy.

The original dialogue was recorded by the core cast in a Connecticut farmhouse, but substantial rewrites (unusual for Anderson) meant tearing across the US and Europe to grab an hour or two with his scattered actors. The models, which were either destroyed or distributed between cast, crew and studio after the shoot, took a year to build.

By animation’s big-bucks standards, Fantastic Mr. Fox was only a modest hit, but its idiosyncratic charm brought audiences and critics back on side, earning him his first Oscar nomination since The Royal Tenenbaums. “I’ve seen enough peculiar things happen in movies,” he says. “If you have something you really want to do, just do it and see what happens because it’s just as likely to go one way as the other. That’s what we did with this. We just did what we wanted.”

PART 7

MOONRISE KINGDOM

2012

It’s hard to imagine Anderson pulling off Moonrise Kingdom’s slapstick energy and crowdpleasing verve without having first made Fantastic Mr. Fox. In fact, he used some of the same techniques. “I knew how fast we were working and we were making a bigger movie than we had the budget for. I thought, ‘I’ll make fewer mistakes if I plan this way.’ Each time I make a movie I take something from the last one and continue it.”

Exploring the impact of the elopement of two 12-year-olds on a small community in 1965, it’s a powerful blend of whimsy and danger. Sam and Suzy’s relationship was inspired by Anderson’s own youthful crush, and the way they cling to their books and records as if they’re driftwood in a stormy sea was also drawn from the director’s childhood. “I thought these two kids ought to have these talismans. When I was about that age I had objects which were crucial to me. I had this bag of Pilot Fineliner pens and a Zulu necklace from the New Orleans Mardi Gras and I carried them everywhere.”

Rigorous preparation and canny use of analogue special effects made Moonrise Kingdom, his second-biggest hit, feel like a bigger production than it was. “I wouldn’t have minded having five more million dollars but I would have had to wait,” he says. “So my choice was, ‘Let’s just do it, I don’t want to wait.’”

PART 8

THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL

2014

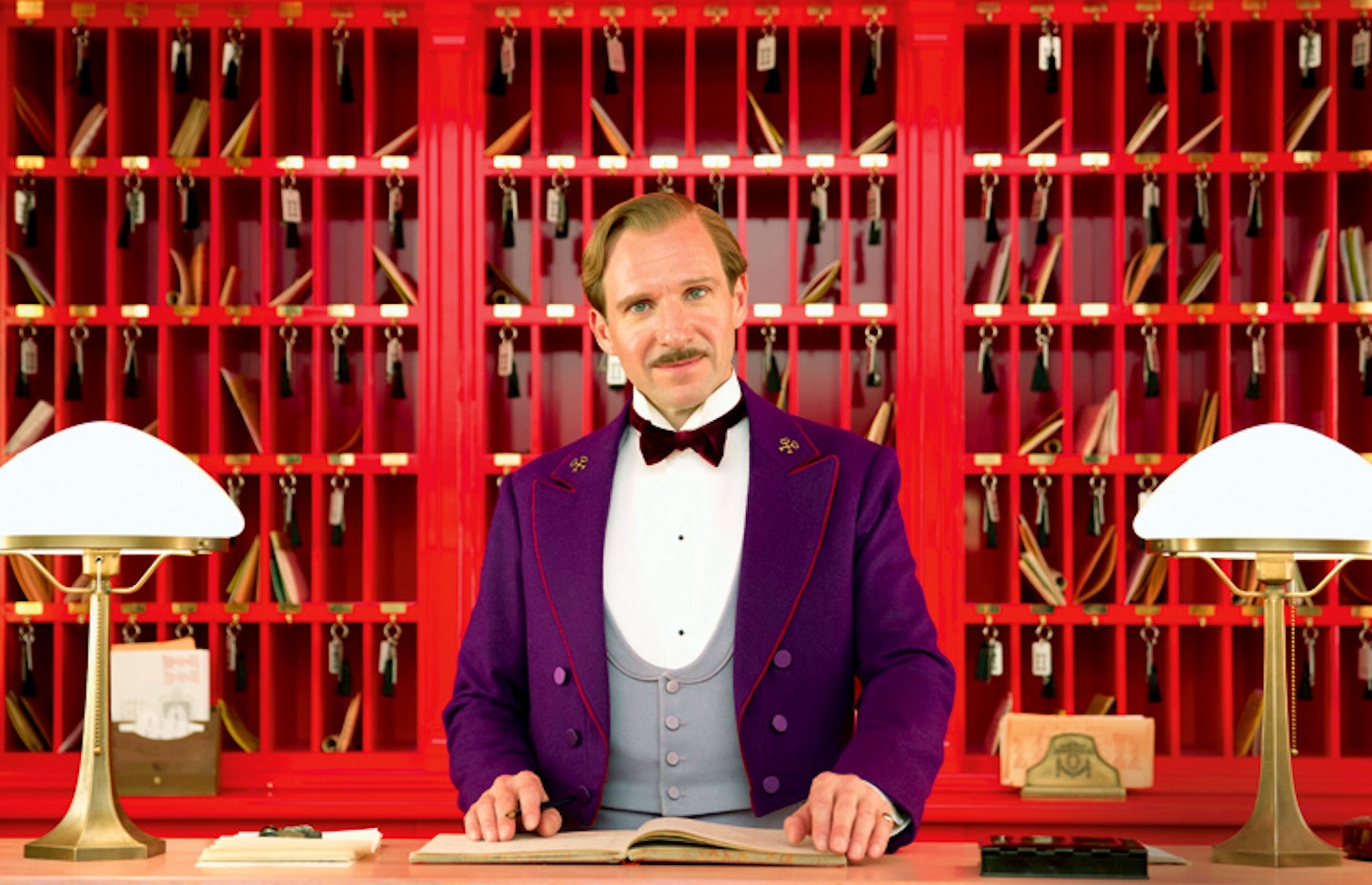

Anderson’s eighth movie revolves around Ralph Fiennes’ bravura comic performance as hotel concierge Gustave H: vain, imperious and manipulative yet loyal and generous. “He’s an unusual character,” the director says. “We haven’t seen this guy before.” The essence of the role originated in a story Anderson wrote with his friend Hugo Guinness, a British illustrator. “It was the way he talks. We had this story about a friend who dies and leaves him a painting and his family doesn’t want him to have it. It was written in a notebook and it was set in the present I think, in France and England. Just a section. That was all we had.”

Then Anderson realised he could make Gustave a concierge and relocate him to the between-the-wars milieu of Austrian writer Stefan Zweig: the Russian-doll narrative, he cheerfully admits, was “completely stolen from Zweig”. He travelled around east Germany and the Czech Republic, interviewing concierges and piecing together the country of Zubrovna, an imaginary Hollywood backlot version of 1930s Europe, from models and details of real locations.

A breakneck caper framed by war, tyranny and random tragedy, it takes Anderson’s love of tonal extremes to new lengths but, as ever, he insists that some of its structural elegance was subconscious. “One thing I only saw when we got into the editing room was all these scenes with Jude Law and Murray Abraham (set 35 years later) are very quiet and slow and the rest of the movie is super-fast. I never contemplated that. Some of this stuff you’re doing without even processing it.”

He doesn’t yet know what his next movie will be. He’s waiting, as ever, for separate notions to meet and breed a story he can’t resist. “Whatever I have, I’m usually not sure where it’s going,” he says. “One thing I often have is several things that need to be pushed together. I have a few scribbled pages of things and I don’t know what they have to do with each other. I did have one idea but they’re very strange things to be mixing together so I’m really not sure if this is going to add up to something or whether I’m thinking of a few different stories that might take some years to sort out.” He shrugs and laughs, like he’s sure it will work out soon enough. Somehow, in Wes Anderson’s pocket universe, it always does.

brightcove.createExperiences();This article was first published in Empire Magazine issue #297 (March 2014). Subscribe to Empire today{