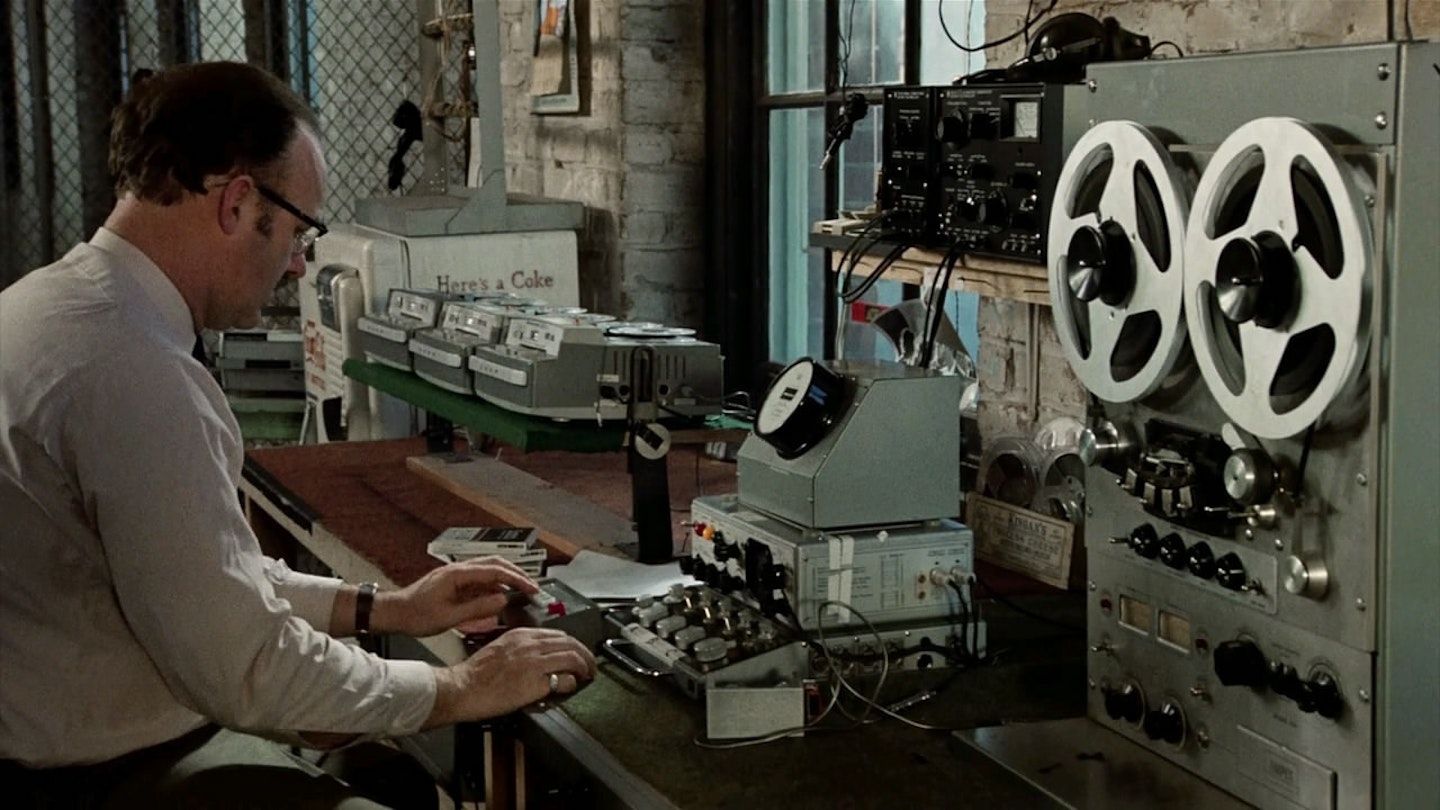

Walter Murch is the Godfather of sound design. A graduate from USC film school, his groundbreaking work with George Lucas (THX-1138, American Graffiti) and Francis Coppola (The Godfather trilogy, Apocalypse Now) has redefined the way we listen and engage with movie sound. But perhaps his greatest work was on Coppola’s 1974 thriller The Conversation. The story of surveillance expert Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), who thinks he has uncovered a murder plot involving the couple he is secretly recording, it use sound in bold and unusual ways. Before a screening organised by No Direction Home, Murch talked to Empire about the film, his iconic sound effects, his ill-fated directorial debut and his current project Coup '53, which he is editing in London.

Why are we still watching The Conversation 43 years on?

At the time people said, “They don’t make pictures like this anymore.” And it is still true. It was a very odd film when it was made. The luck of the situation was that it coincided exactly with Watergate. And it has a great main character, played by Gene Hackman, who says it’s his favourite character. The whole film is told from his point of view, so by the end you have experienced something unusual without knowing how or why.

It’s also a weird mix of things — detailed character study and murder mystery…

That was Francis’ challenge to himself while he was writing the screenplay. He said he wanted to combine [philosphical German novelist] Hermann Hesse and Hitchcock. Those are things that don’t naturally shuffle together very well. So it was a challenge for him in the writing and the shooting, and that challenge continued during the editing.

To what extent did Coppola leave you to your own devices?

Part of the equation was that he was only able to make that film by squeezing it in between The Godfather and The Godfather Part 2, which was a matter of a year maybe. When he hired me to do the editing he said, ”After shooting the film, I am going to have to leave and do pre-production on The Godfather Part 2. So you just carry on and I’ll come back every month or so and we’ll have a screening and see where we are at.” So yes, I was given a free hand. But that’s the way Francis works with everybody. He gives heads of department, and the actors, a lot of rope. Paradoxically you then feel more beholden, given the trust he has extended to you.

In the end, it’s a film about moral responsibility. Should Caul get involved in the lives of the people he is recording, if it saves their lives?

When people heard about the film, they thought it would be The Godfather meets Watergate meets The French Connection. And of course it’s nothing like that. Many people die in The Godfather and The French Connection without any moral accountability. But this film is about somebody who is tortured because he might be tangentially responsible for the deaths of four people a few years ago, and that might now be repeating itself.

You’d previously worked with Coppola and George Lucas on THX-1138. How did you approach that futuristic soundscape?

Unusually — I don’t think it has ever been repeated — I was a co-scriptwriter on the film and also did the sound design. It was being made in San Francisco for a small amount of money. It was a science-fiction film that had a very limited production-design budget, so a lot of work had to be done through the sound, which relatively speaking is very inexpensive. If you use it creatively, sound can punch way above its weight. We used ordinary locations in the Bay area, but through judicious use of production design and unusual use of sound, it succeeded in creating a world in the future.

You next worked with Lucas on American Graffiti. How did you create the creepy sound textures for the scene with Terry The Toad (Charlie Martin Smith) and Debbie (Candy Clark) in the woods?

The scene in the woods is one of two that don’t have music. It was designed in the screenplay to have no music, just to give you a relief from the constant barrage. It was shot in Northern California. They are walking by a drainage canal and there is a eucalyptus forest to right. Eucalyptus trees — which I know very well because I lived among them myself — make a series of strange sounds when the wind blows through them. I went out and tried to record that. I was partially successful. I got a lot of wind but not a lot of the creaking sound. I was listening to the wind with my headphones on back at the studio. In taking the headphones off, the creak of the ear-pieces against the headset made what I thought was exactly the right sound. So I did a whole series of recordings manipulating and practically destroying this plastic head-set, then slowed it down and edited it to give a series of spooky sounds.

You worked on all three Godfather films. Ironically, perhaps the most powerful use of sound is the silence at end of The Godfather Part 2…

That just happened spontaneously in the mix. We had sound effects prepared for that. It’s a scene of Michael sitting by the lake and there is a slow camera move in on him with a vacant expression on his face. As the camera moves in, I just started fading the sound out much too early. As it gets into him, the rest of the world fades away and you are left with this big close-up with absolutely no sound. It’s a kind of negative space, which is somewhat apt for where he finds himself as a character.

How did you come up with the iconic helicopter sounds at the start of Apocalypse Now?

None of the opening eight minutes was in the screenplay. That was something that emerged over the course of editing the film. You see these helicopters in super-slow motion, which immediately suggests a different kind of sound. So we came up with this sound that we characterised as the “Ghost Helicopter”, for want of a better name. It was just the blade of a helicopter and nothing else. In my original sketch, I called it a bat-like sound, a wamp-wamp-wamp-wamp sound.

You have only directed twice — Return To Oz and an episode of The Clone Wars. Why haven’t you directed more?

After Return To Oz, which was a critical and financial failure at the time, I tried to get a number of projects off the ground. But either because of the projects I was interested in or the bad reputation I had because of Return To Oz, nothing took off. I kept at that for three four or five years, but I had a family to support and kids going to school, and I couldn’t sustain it.

A certain generation of Empire readers feel very fondly about Return To Oz...

I think the misadventure of the film in theatres was down to a couple of things. The audacity of trying to make a sequel to The Wizard Of Oz upset a number of people and the fact that it wasn’t a musical upset more people. Then the management of Disney had changed twice by the time the film was ready for release. The new management — the Eisner/Katzenberg management — handled it not even with kid gloves, but with tongs, as they sent it out into the marketplace.

And finally, what are you currently working on?

I am editing Coup '53 in London. It’s an independently-financed longform documentary about Iran and the West circa 1953. There was a coup planned by MI6, but staged by the CIA and BP, to push democracy aside in Iran and install the Shah as a monarch/dictator to ensure that the oil would continue to flow unimpeded. That’s actually the first in a series of tenpins that have been knocked down historically and, certainly for Iranians, it’s the origin of all their problems that have bedevilled their relationship with the West over the past 64 years.

This might be glib, but it seems to be acting as an unofficial prequel to Argo?

At the beginning of Argo, there is a recap of those events. The interference of the West — let’s say the US and Great Britain — installed the Shah. The Shah was armed with the Savak, this powerful secret service which had torture rooms available to it. He created 25 years of anguish in Iran that eventually spilled over and culminated in the Islamic revolution in ’79. Arguably if we hadn’t interfered, the Islamic revolution would not have happened.

Special thanks to No Direction Home, the director’s community. For more information, head to www.nodirectionhome.com.