This week sees the debut of Empire’s stunning Hobbit issue, and to get you in the mood to head back to Middle-Earth we’re reprinting some classic Empire features on Peter Jackson’s first Tolkien trilogy. Today, here is Ian Nathan’s piece on The Two Towers, originally published in issue 163.

DAY ONE: picture, if you will, a scene of such refinement and tranquillity it was surely dreamed up under the porcelain gaze of Merchant and Ivory. As a prelude to luncheon, a string quartet gently evokes a touch of Bach in a minor key, tablecloths are being straightened and napkins folded, and from an adjoining room spills the aroma of food preparation. Order is everywhere, a hushed expectation of the meal to come. At a corner table, three Orcs are deep in conversation, their gnarled heads leaning close together; the ugliest of the trio (this is a thin distinction), whose nose seems to have been riveted several times, sucks idly from a carton of apple juice.

We may need to adjust the picture. The room is, to say the least, ramshackle; walls of crumbling brick decorated with ‘Elf’ vandalism reach inconclusively to the corrugated roof. Outside the rain is pouring like the end of the world. Then, as if some far-off bell has sounded, the room is suddenly engulfed with all manner of beings. More Orcs join their brethren, a small fellow with pointy ears and clown-sized feet wrapped in bin-liners has already got a plateful, and, as if it is the most normal thing in the world (which round here it is), Gandalf the White, Saruman the (formerly) Wise and King Théoden of Rohan saunter across to a table, waving casually to crew members.

Welcome to Catering, Middle-earth, Miramar Studios, Wellington, New Zealand. A place where anything goes, especially the chilli if you’re not quick to the queue. “Do you recommend it?” Saruman enquires of Empire, looking suspiciously at the dish of the day, obviously mistaking your intrepid journalist for one of the catering staff. “Hmmm, better not,” he decides, patting his stomach. “Have to be on set this afternoon.” Despite the sudden tumult (and the Orcs have become quite unruly), the quartet — a weekly civility introduced by producer Barrie Osborne to salve weary brows — plays on regardless.

It’s June 2002, and supplementary shooting — the process of ironing out the final wrinkles in the second film — is almost complete, leaving only the toil of post-production to continue apace until the December debut of The Two Towers. It was a hell of a kick-off, but it means nothing if this movie fails to match Fellowship’s giddy heights. So no-one is lapping up the successes of the recent past — the Oscars, the box office, or the critical acclaim. Every drop of sweat is devoted to getting the new film right.

“It was shot at the same time as Fellowship,” says Peter Jackson later — the sheer workload tending to keep him manacled to the sound stages. “Obviously it has the same sensibilities working for it — the same writers, director, cast, DP; everything is a continuation. But it has a much different tone from Fellowship, and that’s ultimately a healthy thing. In The Two Towers, the story centres more on the world of men, which gives it a more realistic, historical feel — a little in the direction of Braveheart.”

There’s also the arrival of CGI curios Gollum and Treebeard, and the cataclysmic hellfire of the Battle Of Helm’s Deep in a narrative splintered across storylines. This is the dark one, people mutter. While out in the real world, anticipation is boiling into a frenzy. The confidence, though, is palpable. The unit publicist guiding us around takes on the breathy, enthused tone of a Disneyland host: nothing is off-limits; the paranoid secrecy of a Hollywood set doesn’t translate into Kiwi. They’ve got nothing but pride in their accomplishments, and they just want to share it. Time to explore.

%20*Clockwise%20from%20left.%20Gandalf%20The%20White%20(Ian%20McKellen)%20prepares%20for%20filming.%20Bernard%20Hill%20as%20King%20Theoden.%20Merry%20(Dominic%20Monaghan)%20and%20Pippin%20(Billy%20Boyd?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

You can reach the Golden Hall of Edoras via the ruins of Osgiliath and the Dead Marshes. This may not exactly adhere to the copious maps that Tolkien personally provided for his books, but the publicist is keen to show off some of the backlot’s exterior sets, and there’s the opportunity for a toilet break. The journey goes via a 30-foot rock escarpment made of industrial polystyrene. “They pride themselves on their rock,” she boasts. A bit like Deep Purple.

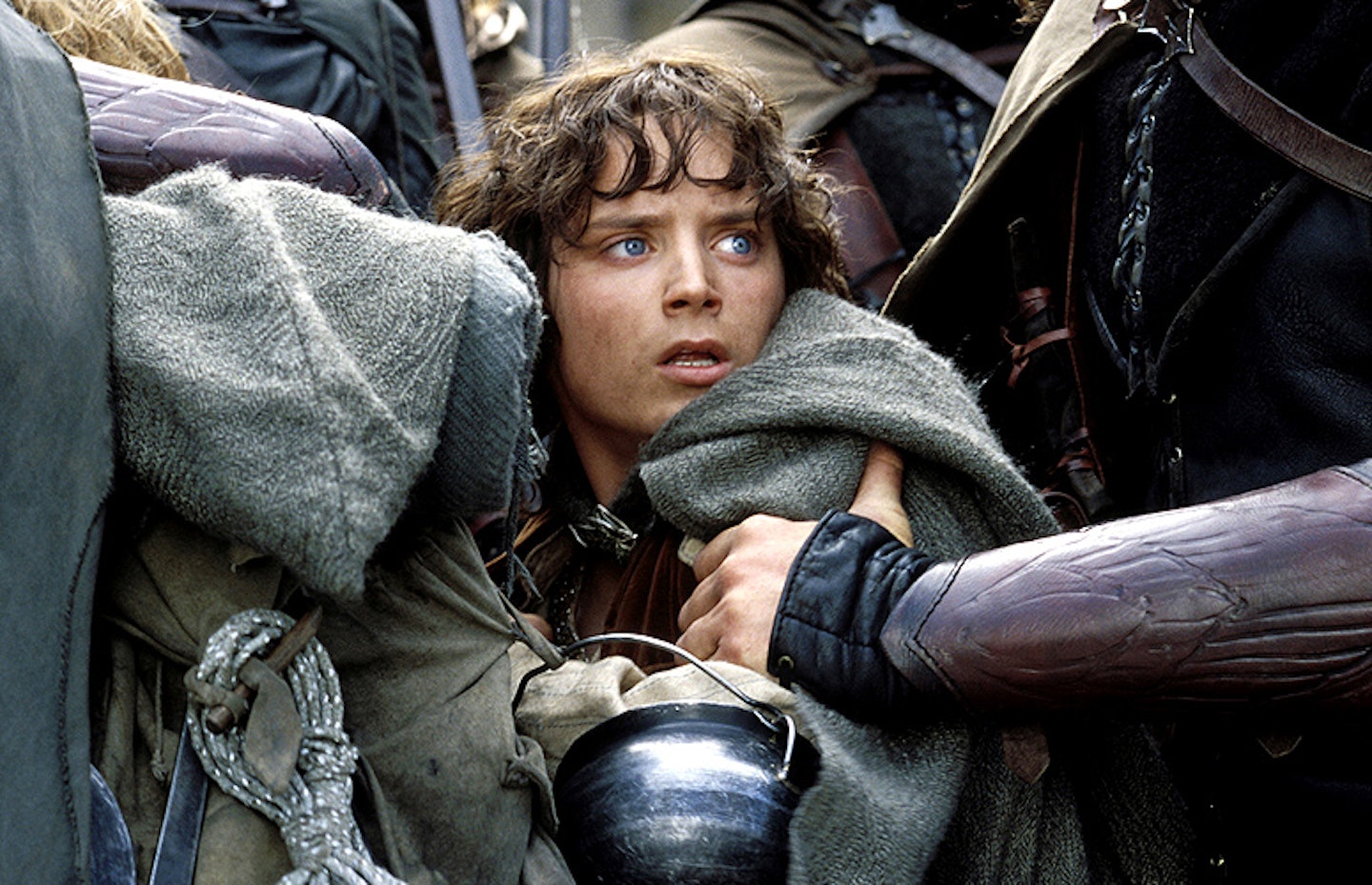

Tolkien warns that you stare into the Dead Marshes at your peril — the long-deceased spirits of slain soldiers are likely to stare right back at you. Yet, in the interests of journalistic integrity, Empire takes a peak into the small, purpose-built marshland complete with clumps of real sedge and moss. The water, bubbling out of a nearby pipe, is freezing, and the only sinister apparition to be found in its depths is an empty Coke can. Is this product placement? Sean Astin, Elijah Wood and Andy ‘Gollum’ Serkis were busily squabbling here only a week ago. Make your own deduction.

The fabulous, Nordic-flavoured carvings of the Golden Hall, royal palace of Rohan, lie on Sound Stage A, which is also currently occupied by an outcrop of Fangorn Forest (being dismantled) and some kind of torture chamber belonging to Christopher Lee. The economy of space is a marvel; the studio may seem cluttered, a kind of Middle-earthian junkyard ringed by the stalks of lighting rigs, but one glance into the monitor and there is Théoden’s massive throne room, carved straight out of the pages of Tolkien’s vast antiquity. The place is alive with activity, and dressed in scarlet leather, a cloak billowing behind him, Bernard Hill’s noble Théoden wafts past.

Word has it that Gandalf is ready. Ushered quickly from the gold-leaf splendour of the echoing hall, we reassemble in Catering. Here, Sir Ian McKellen, back in a warm sweater and jeans, is sitting at a table with the comfortable air of a man entirely at home. “It’s a very nice atmosphere,” he says happily. “It’s almost like making a home movie. It just happens to be a home movie that the whole world likes!” Hold on a second, isn’t he meant to be dead? The last time we saw Gandalf he was plummeting into the pits of Khazad-dûm, trailing a rather narked Balrog. The prognosis wasn’t good. We’ve wept rivers of tears for the Wizard... and he’s alive?

“He’s sent back to finish the job that he did not complete,” returns McKellen — as if a mere Balrog could put a crimp in Gandalf’s staff. “He is reborn, literally. He is now Gandalf the White, more energetic; he’s a commander, a samurai. He’s got a job to do and he’s not going to

be distracted this time.”

Indeed, Gandalf will now be resplendent in white robes, his hair and beard the colour of snow, and as McKellen puts it: “much more manicured”. Acting as a military tactician, he will lead the charge against first Saruman’s hordes and then the might of Sauron; the idea being to distract his enemies from the Ringbearer’s quest. “Unlike some action heroes,” he chuckles, tickled by the notion of being classified in the same bracket as Vin Diesel, “we do see Gandalf off duty. He’s still very humane.”

%20%20*%22The%20Ring%20comes%20from%20each%20of%20us.%20It%20resides%20in%20each%20of%20us%20as%20the%20potential%20for%20making%20selfish%20choices,%20as%20the%20potential%20for%20attempting%20to%20control%20the%20worlds%20of%20others.%22*%20*Viggo%20Mortensen*%20%20

“It’s a very complex story. The Ring is not evil in itself, any more than Mordor or Sauron themselves are. On the surface, the plan is to drop the Ring into Mount Doom, if possible. I believe the Ring is not one thing. The Ring comes from each of us. It resides in each of us as the potential for making selfish choices, as the potential for attempting to control the worlds of others. Aragorn and Gandalf are trying to find a way to get this job done, they have to find a way to unite people, to reject the impulse that is the Ring.” It’s not the classical reading of the book, but he’s willing to admit there’s still plenty of action for the rugged hero in part two. “He’s much more of a soldier in this one, he is finally coming to terms with his destiny to be king.”

Talking of which, in what seems to have become a game of celebrity tag, Bernard Hill appears over Aragorn’s shoulder and pulls a mock yawn. The guys have become good friends. “Hey, it’s his majesty,” sneers Mortensen good-naturedly as he gets up to go. Isn’t it always the same? You don’t see a king for ages then two arrive at once.

“Théoden and his kingdom are in serious decline when we see him at the start of film two,” begins the 57 year-old Hill, who has also returned to his civvies. “His story is to do with the coming out of that, a rebirth, if you like.”

With his mind polluted by Saruman’s lies, Théoden is drawn back to reality by Gandalf, finally facing up to the fact he has to go to war. “It is an interesting dynamic, the idea that the world of man would be destroyed. You’re talking about genocide. Théoden has to shake off the evil and become as pure as he can again. It’s almost like he grows up. He comes from a birth, goes through the middle years and becomes old and wise by the end.”

Hill was well-versed in swordplay from his Shakespearean days. It’s the horses he wasn’t keen on, tricky given Théoden heads up an equine-orientated nation. Week upon week in the saddle were required to instil the requisite skill. That and a co-operative pony between his legs. “Mine was called Depend,” he laughs, “for ‘dependable’. And nothing would rattle him. Viggo’s bloody nag kept hitting reverse gear and murdering the shot.”

For Friday afternoon tea there’s a raffle. And despite most of the cast and crew having worked on the films for nearly three years, the notion of winning a Lord Of The Rings action card game or set of die-cast, three-inch Hobbit figures, still fills them with delight. There is much whooping and hollering going on — the string quartet has finally given up the ghost. Our publicist, clutching a box full of names, stops by Bernard Hill to pick one and read it. With that an Orc fists the air in triumph and runs forward to collect his commemorative cap. Bet this didn’t happen on Titanic.

DAY TWO: scampering through the drizzle, we are guided to the interior of Orthanc where we are granted time to have a poke around. On closer inspection, Saruman’s Gothic clutter starts to yield its secrets. Bottles of mysterious gloop contain the actual remnants of fossilized amphibians. “Everything has to be authentic,” the publicist explains. “There was a parchment written in Elvish which said something like, ‘Gary was here!’ Peter wasn’t having it. There are people out there who know Elvish.” That said, upon opening one of the dented books, weathered to fit the scene, it turns out to be an anthology of the New Zealand Gazette. Saruman must get it on subscription.

“Sit on the throne,” the publicist implores, and Empire perches on the ornate seat and ponders for a second the oddity of the place. This may be simply a movie set made of fibreglass and wood, but it blurs around the edges where Middle-earth squeezes in. No-one calls it a set — they call it Orthanc. Mind you, the ’60s-style, brown armchair, lodged behind a bank of flickering monitors, isn’t very Tolkien. Even if it has been emblazoned with the White Tree of Gondor. And has Peter Jackson sitting in it. “Oh, the props guys did this for me,” he says, pointing out the heraldic symbol for Minas Tirith. “We got the chair for Harry Knowles when he visited.”

Jackson, on set, is in clover. The crew buzz around him as if responding to telepathic instructions. They’ve been at this so long, they can almost read his mind. “We’ve got to get one more shot before lunch,” he explains, clutching a ragged piece of paper. “It is helpful to have a line for an earlier scene shot years ago. The population of Edoras is fleeing to Helm’s Deep, and I wrote a line to explain this with Wormtongue informing Saruman it is a good time to attack.” On the paper is a line of dialogue hastily scribbled in Biro. “I’m in make-it-up mode,” he laughs.

With the sweep of a black cape, his face as ashen as nausea and distinctly short on eyebrows, in steps Brad Dourif, a.k.a. Gríma Wormtongue, despicable right-hand man to Saruman. The poison in the heart of Rohan. His voice a whisper of evil, eloquent but starved of oxygen. Dourif, rumour has it, likes to stay in character. Spotting Empire, an oily smile turns his lips: “So, you’ve come to see me fail?”

Not at all, but when Dourif, equipped with new jotted line, begins the scene direct to camera, he jerks and judders, frequently missing words as Jackson calmly asks him for another take. Then, like a key slotting into place, you can feel the line click and the insidious menace of Wormtongue swells onto the monitor.

“It’s very easy, in a way, to be the bad guy,” admits the 52 year-old actor, famed for his array of slimeballs, dirt-diggers and out-and-out loonies. “You are in control. Things don’t happen to you — you do them to other people. If it wasn’t for the devil there would be no story.”

Dourif has worked hard with the screenwriters on fleshing out Wormtongue’s tortured backstory. Despite his obvious wickedness, including unhealthy designs on Miranda Otto’s Éowyn, he is a tragic figure who has spent his entire life ugly and despised. “He was a human who has turned evil,” he insists. “He has totally come under the sway of Saruman and finally, of course, Sauron.” Given his sharp, duplicitous mind, Wormtongue has worked his way up to become advisor to Théoden. However, Wormtongue’s double life is in for a rude awakening when Gandalf and the gang ride into Rohan.

Wormtongue’s real boss, meanwhile, Christopher Lee, is keeping a dignified pose, despite the fact various people are fiddling with his skirts. They’re trying to mike him up while he continues to make his point. “It has been very satisfying coming back,” he says, his prosthetic nose wobbling at eye-level. Saruman, let’s not forget, has the right arse in the second movie. His plan to grab the Ring has been foiled, so he decides to launch an army to wipe out mankind. Lee, in contrast, is feeling content. “It’s easy to feel confident,” he asserts as one of the chief clairvoyants of the triumphant debut, “but I don’t have fears as to whether it’s going do less business or whether it’s not going to do as well. I think the anticipation is probably greater this time around. This movie is going to be better.”

DAY THREE: a short drive away, in another nondescript corner of Miramar, lies the Weta Workshop, the soul of The Lord Of The Rings operation. Here is where dreams and nightmares are created, the contents of which could float on eBay and probably recoup the entire budget of the film. A Willy Wonka factory of props and models, the detail of which is mind-blowing. Empire grasps the shards of Narsil forged from sprung steel in the in-house smelting works, the sword that severed the Ring from Sauron’s pinkies. The publicist passes over Boromir’s hefty blade: “Careful, you could have someone’s eye out with that,” she quips. Actually, you’re more likely to have someone’s head off.

There is a room devoted to every different Middle-earth locale: The Shire, Rohan, Gondor, Mordor… Hung up on a coat rack is this season’s Orc couture in a variety of fittings. In all, 48,000 different items have been made over five departments: armour, weaponry, special make-up, miniatures and maquettes (the sculptures of creatures used as scanning guides for the computers). “We’ve been doing this for five years,” chirps a Weta expert on cue, “and we’re still going strong.” The industry and skill on show is staggering. Peter Jackson gives them copious notes, the artists conjure Tolkien’s dreams onto paper and Weta turns them into three-dimensional reality. The net result, meanwhile, sits in a glass cabinet near the entrance, getting a quick buff from a cleaning lady.

“Coming home with the Oscar finally solidified for everyone that we could stand up and be proud,” asserts Richard Taylor, the mastermind in charge of Weta, whose vocal pitch is permanently on clarion call. “It had been recognised that we weren’t the poor cousins down in New Zealand.”

Taylor’s 12-inch statuette for Best Visual Effects was carried home in a Tesco bag. When he landed at Wellington airport, the innately modest genius who has worked with Jackson since the humble beginnings of Meet The Feebles and Braindead, was startled to find the ground staff had laid out a red carpet and the entire arrival hall, along with all his co-workers, was cheering dementedly. “I had managed to buy 100 miniature Oscars,” he recalls, “and I had them in two big rubbish sacks. So I was able to hand out Oscars to everyone. It was a real scramble, then everyone drove out of the airport with them mounted on their roof-racks and bonnets. It was crazy.”

In the corner of a warehouse area, its back to the room like a scolded schoolboy, is what seems to be a large, vaguely humanoid tree. There is just enough room to squeeze in front and find the beard made out of vines; this leads you to a pair of eyes the shade of honey, with brows as thick as a forearm. This is Treebeard, the exotic companion for Merry and Pippin, who will prove a godsend to the good guys. As an Ent, he is also one of the potentially silliest additions to The Two Towers’ creature culture. “You have to find a way of creating something that isn’t immediately risible,” says John Rhys-Davies, who will add the Ent’s voice to his performance

as Gimli. “When you think about a walking tree, laughter is the response. You have to avoid that.”

Yet, as Jackson is at pains to point out, “He’s not a walking, talking tree, but rather a shepherd of the trees. The trees have the ability to move and kill, but they have to be kept under control in the forests of Fangorn. The forests have shepherds who are supposed to look after them. That’s what Treebeard is. His skin is like bark and moss, so he looks a bit like a tree.”

Born out of Tolkien’s predilection for the woodlands around Oxford — and designed to echo his ecological concerns — Treebeard will mainly be a CGI creation; this animatronic version is used for the close-ups with Hobbit actors Billy Boyd and Dominic Monaghan. He is also the oldest creature alive, and has proved one slippery customer to nail. “We plunged in and just experimented,” sighs Rhys-Davies, whose natural Welsh basso is as rich as malt whisky. “You cannot do exactly as it is in the book because of his slowness — you can’t afford that on film. I’ve had nightmares about this; it was both frightening and very satisfying to find the Treebeard voice. I can’t tell you that it actually works, all I can tell you is that Peter doesn’t let go of things unless he is happy. I have only heard one finished line and it seemed to me pretty damn good.” His voice subtly takes on a deeper, mellower ring. Is that a hint of ancient bark

and the soft rustle of leaves? The actor grins. “I do know we created a moment in the Treebeard sequence that isn’t actually in the book,” he adds enticingly. “It will be one of the most astounding moments in the film. It should make your hair stand on end.”

In a smaller room, thick with the scent of rubber and sawdust, the maquettes are sculpted. A large display case in the corner contains a detailed model of King Kong wrestling with a dinosaur. “That was made when Peter considered the movie,” the publicist says of the project that was put into turnaround by Universal. “I’m not sure he’s going to do it anymore.”

A row of life-sized heads, each subtly different but quite revolting, adorn a bench. “Oh, that’s the change into Gollum,” says our guide, explaining that we will witness a time-lapsed transformation from the Hobbit Sméagol to Gollum the emaciated ghoul, cowed by the corruption of the Ring over 500 years. “I personally think one of the scariest things in The Two Towers is the Frodo/Sam/Gollum relationship,” says Jackson of the monster who becomes a key player in film two. “We took a lead from Tolkien, but have gone a bit further into the area of the psychological thriller.”

There are two things you need to know about Gollum. Firstly, he’s a headcase: the former custodian of the Ring, addicted to its power and tormented by its absence. Secondly, he’s played by British actor Andy Serkis, although Serkis won’t, strictly speaking, be on screen.

“We are doing a CG character but having a human actor put his stamp on it,” continues Jackson, fully cognisant of the dangers of ‘going Jar Jar’. This is different, he asserts: Serkis is acting the entire role in a motion capture studio, his every movement logged on a computer, and with the aid of 45 animators turned into the character. It’s a process that has been evolving throughout the shoot.

“When I arrived there were vague notions of doing this thing called motion capture,” says Serkis, admitting he may have landed the part when they realised he bore a striking resemblance to their concept art of the creature. “The whole ethos of the way Peter works is making it more truthful and not just a special effects movie. We pursued ways of making Gollum as fully integrated as possible.”

We’ve moved to the motion capture stage. In truth, another Miramar warehouse smelling like a school gym. Serkis is in a skin-tight Lycra get-up, doing exaggerated Matrix poses to make the crew laugh. Dotted across his catsuit like overgrown sequins are data reflectors ‘capturing’ his movements. “He is an extraordinary character,” considers the 38 year-old star of 24 Hour Party People. “He is the audience’s key into what the Ring does to you. He is a Ring junkie. He was a Hobbit, and I like to think he could have gone another way. Something very human.” Specifically, his frail psyche has fractured into two halves: the docile, subservient ‘Sméagol’, and the treacherous mental carapace of ‘Gollum’, who might yet betray Frodo in the desperate hope he can regain possession of the Ring, his precioussss!

Serkis can’t resist giving a taster of the voice, his normal baritone strangled into an agonised wail, partly based on the sound his cats make when tormented by a fur-ball. “It comes from where I think his pain is trapped. For him it was his throat. It’s not always easy — I had to do

a scene the other day eating a 12-inch worm while doing the voice… It was jelly, not a real worm.” He takes on an announcer’s prim tones: “No worms were harmed in the making of this film!”

%20

DAY FOUR: we’re in Lilliput, as in the miniatures studio. Everywhere you look are impossibly detailed models of the various towers, cityscapes, fortresses and palaces from the three films. Empire strokes the precision-built exterior of Barad-dûr at 1/66th scale and wonders how big the Airfix box would be. Smoked with dry ice and bathed in artificial sunlight, these bedroom-sized citadels take on the gigantic dimensions we witnessed in Fellowship. That’s how Jackson wants it — none of this digital gloss, but real film in real cameras making their dynamic swoops for real. With a purpose-built, motion-controlled camera rig, today they have been skimming over the remnants of Osgiliath and circling the tower of Zirak-zigil, where Gandalf finally clobbers the Balrog.Alex Funke, a jovial maestro of the technique, is trying to explain the process of melding shots of a four-foot Minas Morgul into a human-sized set-up. Spotting the envious expression on Empire’s mug, he emphasises he won’t be selling Minas Tirith after the films are finished (no matter how well it might set off Empire’s living room), and that we really should come and look at Helm’s Deep, because in The Two Towers this one is going to bring the house down. Let’s put this simply: Helm’s Deep is a stone fortress where the population of Rohan have run for cover and which the massed ranks of Saruman’s Uruk-hai army are endeavouring to smash to smithereens. Viggo Mortensen, Orlando Bloom, John Rhys-Davies and Bernard Hill spent months of night-shoots enacting its furious battle as hundreds of extras dressed as Orcs and soldiers gruffly laid into one another washed by the rain machine. It will have the gigantic heave of a David Lean spectacular, backed up by the digital creation of teeming Orcs spilling over the various models.

DAY FOUR: we’re in Lilliput, as in the miniatures studio. Everywhere you look are impossibly detailed models of the various towers, cityscapes, fortresses and palaces from the three films. Empire strokes the precision-built exterior of Barad-dûr at 1/66th scale and wonders how big the Airfix box would be. Smoked with dry ice and bathed in artificial sunlight, these bedroom-sized citadels take on the gigantic dimensions we witnessed in Fellowship. That’s how Jackson wants it — none of this digital gloss, but real film in real cameras making their dynamic swoops for real. With a purpose-built, motion-controlled camera rig, today they have been skimming over the remnants of Osgiliath and circling the tower of Zirak-zigil, where Gandalf finally clobbers the Balrog.Alex Funke, a jovial maestro of the technique, is trying to explain the process of melding shots of a four-foot Minas Morgul into a human-sized set-up. Spotting the envious expression on Empire’s mug, he emphasises he won’t be selling Minas Tirith after the films are finished (no matter how well it might set off Empire’s living room), and that we really should come and look at Helm’s Deep, because in The Two Towers this one is going to bring the house down. Let’s put this simply: Helm’s Deep is a stone fortress where the population of Rohan have run for cover and which the massed ranks of Saruman’s Uruk-hai army are endeavouring to smash to smithereens. Viggo Mortensen, Orlando Bloom, John Rhys-Davies and Bernard Hill spent months of night-shoots enacting its furious battle as hundreds of extras dressed as Orcs and soldiers gruffly laid into one another washed by the rain machine. It will have the gigantic heave of a David Lean spectacular, backed up by the digital creation of teeming Orcs spilling over the various models.

“It takes place mostly at night,” boasts Jackson, who was fed the growing miracle of the scene’s effects on laptops while busy mustering the troops. “It was so complex we filmed for about four months of nights. Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli have ended up there with about 300 soldiers, so it becomes them against 10,000.”

“Helm’s Deep was an incredible challenge,” adds Richard Taylor of what is already being mooted as the new movie’s coup de cinéma. “It was achieved using a number of different scales.”

There was the full-sized fortress built in a disused quarry outside of Wellington, a quarter scale miniature that filled a rugby field and a 30-foot scale miniature that occupies the sound stage here. Using a combination of these castles and some crafty compositing techniques, each version will be assailed by thousands of Orcs in front of our dazzled eyes. “It takes three cents of ink and 14 seconds to read the line: ‘The soldier glanced across the plain and in front of them were tens of thousands,’” Taylor says soberly. “To bring that to the screen is a five-year endeavour encompassing 1,000 people and millions and millions of dollars.” He pauses and looks Empire straight in the eye. “Helm’s Deep will go down as one of the greatest epic triumphs of cinema history. It is a scene simply beyond comprehension.”

NEW YORK: on a blazing hot day in late September, thankfully within the air-conditioned confines of a polished hotel suite, Bernard Hill is pretending to be Peter Jackson, Brad Dourif is pretending to be Christopher Lee, and John Rhys-Davies is pretending to be a French female television host, Machiavelli’s Prince and a whale. All are very good.

A host of Two Towers talent has gathered to further talk up the upcoming movie, and to a man/woman/Hobbit/Ent, they are getting into the swing of things. But, let’s start with Elijah Wood, who is still trying to get his head around Gollum. He may have spent six months acting with him, but he hadn’t seen him until this morning. There has been a 15-minute preview of The Two Towers shown, including a five-minute scene of the finished Gollum wrestling with Sam and begging for mercy from Frodo: a sweaty, twitchy, fully-formed creature, oozing out of the screen. He ain’t pretty, but set aside concerns — he really works.

“Wow, it was amazing,” says Wood with a shake of the head. “I’d seen assembly stuff when I did the looping and they hadn’t touched it up. It was really rough and Gollum was a wire stickman.” For Wood’s alter ego Frodo, Gollum is where it’s at. In fact, their relationship becomes the hub of the entire trilogy, each manipulating the other: Frodo using Gollum to get to Mordor, Gollum helping Frodo in order to get close to the Ring.

Wood nods in agreement. “He pities him initially — he sees that underneath that wretched guise is a Hobbit that succumbed to the power of the Ring,” he explains. “Frodo sees that there’s still humanity in this wretched creature, but he also sees what he (Frodo) could become, which is much more interesting. If he holds on to the Ring for this length of time, he could become Gollum. And that’s really frightening. So part of his mission in the second film is to prove that Gollum can come back from that evil place and extract the humanity out of him, because he knows that if he can get that out of Gollum, then he too can be saved.”

You may have already surmised that events for Frodo take a major turn for the grim from now on. He will spend the new movie with only Sam and Gollum for company, and their path will be beset by betrayal and disaster as Frodo sinks under the Ring’s corruptive power and they close in on the perpetual gloom of Mordor.

“If you are doing scenes every day that are filled with despair, anguish, fatigue, cold, anxiety and obsession, all these extremes, it’s an atmosphere you become, oddly enough, comfortable with,” he says, ever the pro. “You don’t actually take that home with you… Although the fatigue I totally took home with me. I have never been so exhausted in my life.”

He pauses for a wistful, ‘you had to be there to understand’ kind of shrug, then perks up again: “It’s weird, I had no concept of what everybody else’s journeys were at that time, I could only see my journey, and so when I see this movie there is so much that I literally have no knowledge of.”

Meanwhile, Bernard Hill is discussing how Peter Jackson was always open to ideas presented by his cast. Eventually. “Yeah, right, sounds great,” he mimics in a soft, peevish, Kiwi accent that is a dead ringer for his boss not being overjoyed at being distracted by Hill’s ‘new idea’. Clearly, the nobility of his role was rubbing off: for a pre-battle team talk, he had the notion of passing along the massed ranks of his cavalry, touching each of their spears with his sword in a sign of fealty.

“It made it into the script and Pete did it,” he says proudly. “But he did it the wrong way round, the silly fucker, because I’m left-handed and he made me do it with my right hand. But it’s a very exciting moment. Pete was great like that, he was so open to stuff.” Hill’s eyes glaze over for a brief moment of reverie, his mind transported back to the tumbling plains of New Zealand; he returns to the Big Apple with a happy grin. “This is going to be a better film,” he asserts as if it has just occurred to him. “You’re very quickly brought into human frailties, human failure, human emotions like loss, grief, jealousy, all those things that people identify with. And there is still the fantasy section — grand Wizards and all that kind of stuff — but even more dynamic.”

An hour later, Brad Dourif is striding about the room, his nose to the ceiling and shaking his fist at the wall. He is explaining what it was like to work with Christopher Lee, for which you need to play the towering British thesp. There are just so many stories. Don’t get him started, he implies, already off and running. “Of course, he knew Tolkien, you know,” he intones in his tidiest, mock-posh English accent; it’s not far off the great man. “He really knew the names of everything. To be honest, he knows everything and everybody on the planet. I mean, you almost don’t believe him, until you hear it is true.”

He plants himself down in his seat again, pulls what can only be described as a Brad Dourif kind of face — the eyeballs are an inch further forward than the rest — and reflects, “You know what was weird about this film? Everybody was signing shit. Now, because of eBay, all this shit really has value. In this respect, it was the most unique thing I have ever done, the amount of shit I signed.”

John Rhys-Davies doesn’t even need a question to get going. Ever the raconteur, he’s up and running on a fresh anecdote before he reaches his seat. “Do you know that French television host, Sophie?” he asks from somewhere left of leftfield. Empire shakes a baffled head. “She is a gift sent down from heaven! Magnificent! You must meet her.”

It transpires that Rhys-Davies hasn’t seen the exquisite Sophie since Cannes last year. She made a lasting impression. “She was interviewing myself, Sean Bean and Viggo Mortensen, about the first film,” he continues in a dubious French falsetto. “’Ah, it was very exciting and spectacular, but what is there is very for the woman to enjoy?’ And she looked at me and then she looked at Viggo and then she *looked *at Sean. ‘So tell me, Sean? How would you seduce me as a woman?’ I love her! I love that girl! Sean, who is a sweet, lovely, gentle soul, was dumbfounded. We were like, ‘Go on, Sean! Go on! How would you seduce the lovely Sophie?’ Well, if you can’t take the piss out of your fellow actors, what can you do?”

Welcome back to the bizarre, wonderful, alternative universe of John Rhys-Davies’ head. And today he is on top form, although Treebeard is still a worry. “How does a tree speak? It’s such a risk, this one,” he wails. “It’s almost Machiavelli, isn’t it? ‘The minds of men are timorous, they are voluble, they are dissemblers, anxious to avoid danger and covetous of game…” Er, quite.

“And then sometimes you’ve got to risk a bit of artistic failure. If I fall flat on my face in this, then it’s my fault.” He holds out his hands, as if waiting for the cuffs. “You know, we even tried to add whale-like communication to his voice.” The Welsh actor sucks in a lungful of air before emitting an astonishing bellow: “Woooooammmmmmmerrrrrrr!!! (approximation only) That kind of underpins the voice. I trust that P.J. has found the answer — I still haven’t heard the finished thing.”

Not one to stay downcast for long, he puffs out his chest like a peacock and resumes his role as chief disseminator of hyperbole for The Lord Of The Rings trilogy. “This film is far more exciting, it is breathtaking. I would say it is almost of a different order than part one. This is the real meat of the story. We haven’t seen a film on this scale in my lifetime.”

%20*Clockwise%20from%20left.%20Legolas%20fights%20for%20his%20life%20(Orlando%20Bloom).%20Gimli%20in%20the%20heart%20of%20the%20battle%20(John%20Rhys-Davies).%20Eomer%20(Karl%20Urban)%20confronts%20Wormtongue%20(Brad%20Dourif?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

**DAY FIVE: **whatever the Hollywood gossips may prattle about over water-coolers and lukewarm lattes, what is evident here, back in luscious New Zealand, is not an issue of making a better film than Fellowship. That was never the point. The driving force for Jackson and his hungry troops is to make the best film possible, to make The Two Towers the best Two Towers possible. One that J.R.R. will look kindly upon from his Middle-earth in the sky. And the key to their realm of ingenuity, craft and extraordinary vision dubbed “Wellywood” is a simple New Zealand tenet: “Never say we can’t do that.” Whatever the obstacle, Jackson and co. have found a way. Trees will walk and talk, CG characters will have substance and texture and not float around absurdly like they’ve been shaken out of Toy Story, and the mood will get darker, more disturbing and far more exciting.

The feeling pervades the whole of the country, the determination that these three films, each different but part of a whole, will be their cinematic legacy to the world. It is not just about the landscape, it is something innate in the people — they could not have been accomplished anywhere else.

Nowhere is this more apparent than at Roger’s Tattooart. Located on the boho parade of Cuba Street in downtown Wellington, on the wall of this grungy parlour is a picture of Elijah Wood mugging away, having just got his Elvish tattoo. As is well known, the entire Fellowship got one (bar Rhys-Davies, who sent his stunt double). They were then followed by Peter Jackson, executive producer Mark Ordesky and Bernard Hill.

According to Roger, who has his own set of facial rivets, Tolkien tattoos are all the rage. Here, and all over the world, The Lord Of The Rings has made a lasting impression. Roger is even thinking of expanding his repertoire for The Two Towers, too. He smiles, stretching the shrapnel. “After all,” he says, “no one ever asks for a Star Wars tattoo.”