There’s a little moment in The Truman Show which I think about a lot. Truman and his college pals are at a ‘50s-style dance in their tuxes, twisting to a twangy, yee-haw version of T Rex’s ‘20th Century Boy’ which sounds like it was recorded at Sun Records. It is, as a guy who’s very much not Marc Bolan sings, just like rock ‘n’ roll.

But it only clicked the second time I watched the film that it was a snapshot of the weirdness which bubbles underneath the surface of The Truman Show. Jim Carrey’s Truman couldn’t possibly be exposed to actual rock ‘n’ roll in case it fired up a spirit of rebellion and mistrust of authority. The shadowy forces behind his life-as-entertainment couldn’t possibly risk their asset becoming a fan of the Beatles and deciding to turn off his mind, relax and float downstream, much less learning about the Ramones and wondering why they were so keen on sniffing glue. So his exposure to pop culture starts and ends in a bubblegum paradise, before the Summer Of Love, and the Altamont Free Concert, and glam’s sequinned freak-outs.

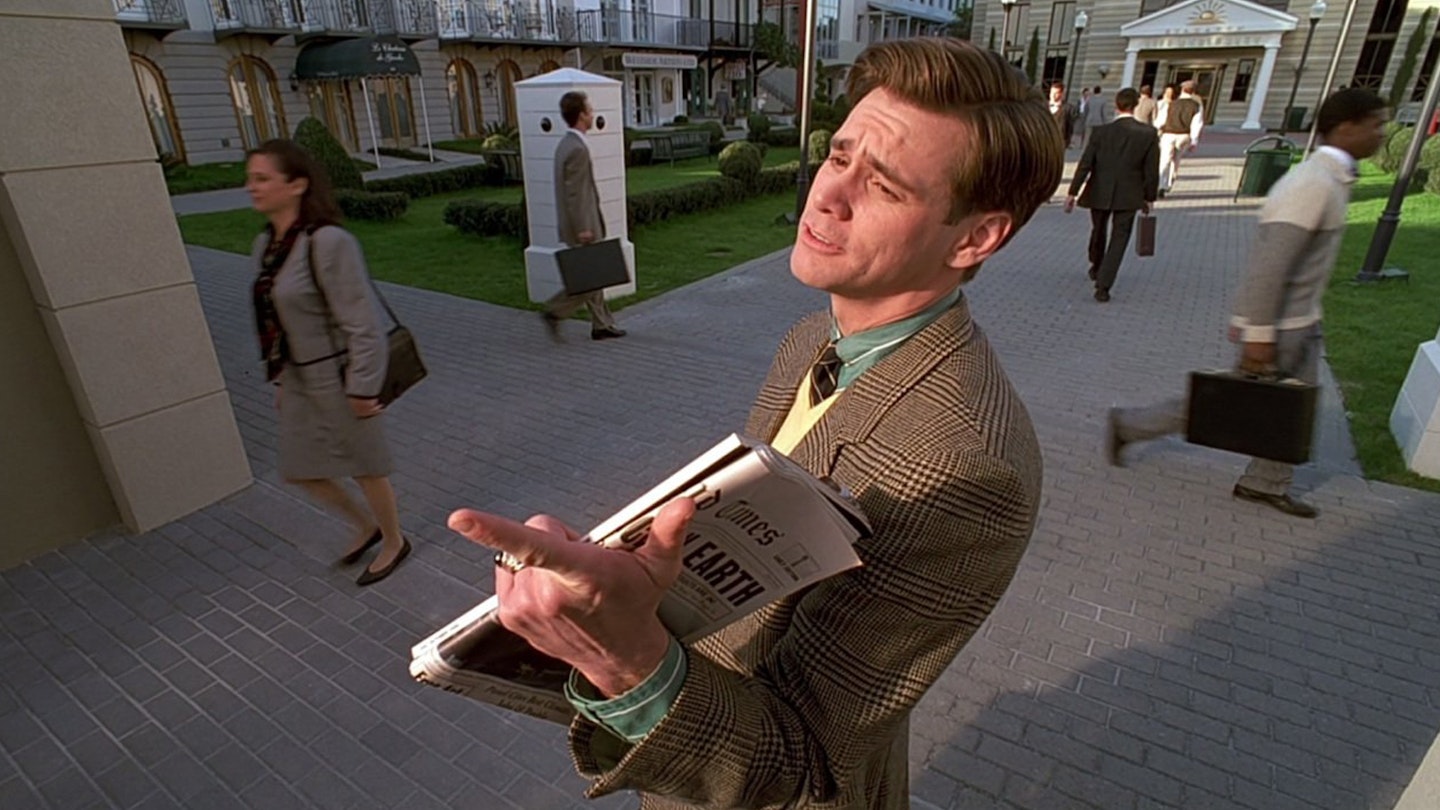

It’s one detail in a movie which is so full of details that it still has layers to peel back now, 25 years after its release. Truman Burbank is trapped on the perfectly-manicured prison of Seahaven Island, but on that island there are thousands of little alleyways like that for audiences to wander down, questions that present themselves the further you stroll. Does his car radio only play classical music to keep him pacified while also helping the production company behind ‘The Truman Show’ sidestep royalty payments? During a phone-in interview with the in-universe director of 'The Truman Show', Ed Harris’ Christof, someone from The Hague tries to ask a question – is that a hint that Christof is on trial for crimes against humanity? Is Truman’s surname, Burbank, taken from the part of Hollywood where his mega-studio home is built? What’s his real name?

The Truman Show is a movie that really wants you to think about these things. From its very beginnings, Truman's world was complete and lived-in. Director Peter Weir put together a bible exploring the world of ‘The Truman Show’ and fictional filmmaker Christof – an Oscar-winning documentarian who’d focused on the homeless, and had intended to follow a baby for one year only, in order to sell baby products off the back of it. Soon, his project grew and grew, and eventually became a whole miniature world.

The idea of a never-off-camera reality show was incredibly prescient – Big Brother only arrived two years later – but it’s not just a finger-wagging lesson from the past about how TV makes you go stupid. (Look at how much joy and togetherness Truman’s story gives his audience – this might be the most pro-TV movie there is.) It’s kind of about everything: God, free will, reality itself. All the big ones are there on Seahaven. The island is a nightmare to rival Brazil in its mundane cruelty. Truman’s seen things you people wouldn’t believe – though only because you people wouldn’t believe that tiny, lumpy version of Mount Rushmore was the real thing.

We’re in on it too. There are frames within frames here: The Truman Show depicts the making of a TV show, and the sets and soundstages where it’s shot, and the screens of the millions around the world who’ve been following Truman’s every move since he was an embryo. And all the while, we’re watching it too through a cinema – or, these years later, TV – screen, an additional layer of artifice. Christof splices Truman’s own memories and flashbacks into what the audience at home is seeing as if he can shuffle Truman’s very thoughts. That, though, is the one thing Christof can’t control. “You never had a camera in my head,” as Truman tells him.

The Truman Show's power comes from the way it paints shadows with bright colours.

The story was originally something more obviously dark. Writer Andrew Niccol’s first drafts ended by following Truman out through that bright blue sky and into the real world, where he walked into his own celebrity for the first time. “He went into his own souvenir store,” Niccol told the BFI in 2018. “There were cardboard cut-outs of himself. It got even more warped in a strange way. He even jumped on a studio tour tram with the guy driving it giving the facts of his life that he didn’t know.”

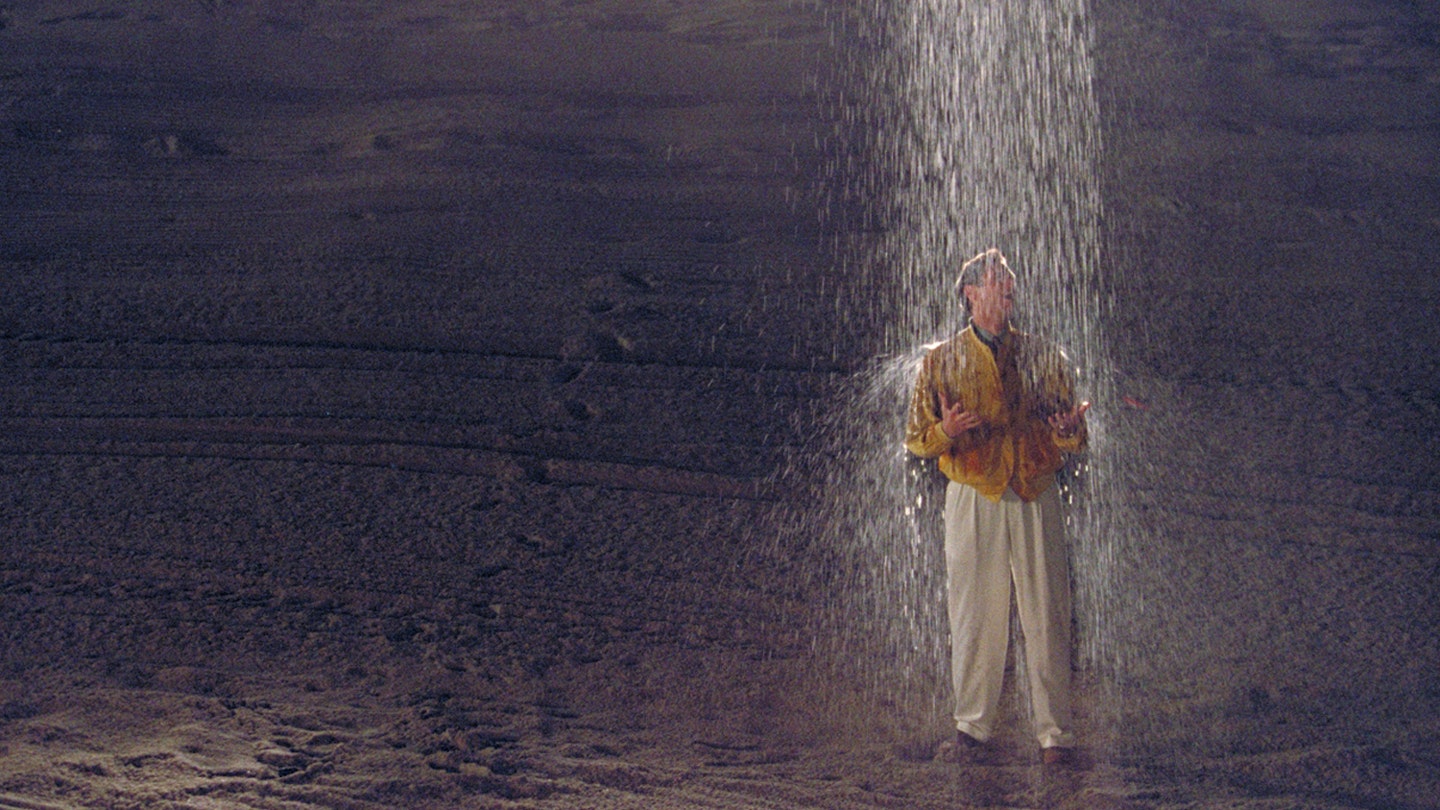

But The Truman Show’s power doesn’t come from its darkness, but from the way it paints shadows with bright colours. Seahaven is safe and controlled, and against that eeriness Weir creates some amazing, chilling images. There’s Truman sitting under a tiny raincloud which chases him across the beach. Later, the entire town stands mannequin-still at their first positions as the sun unexpectedly rises halfway through a manhunt for Truman, suddenly looking like a model doom-town awaiting its fate on a nuclear testing range. And at the finale, those stairs cut into a painted sky which lead Truman to the exit door. It feels like something from a Magritte painting, surreal and poignant but full of foreboding too. After meeting his maker – Christof – Truman walks up those stairs and into the endless blackness. He's being reborn. But what will his next life be?

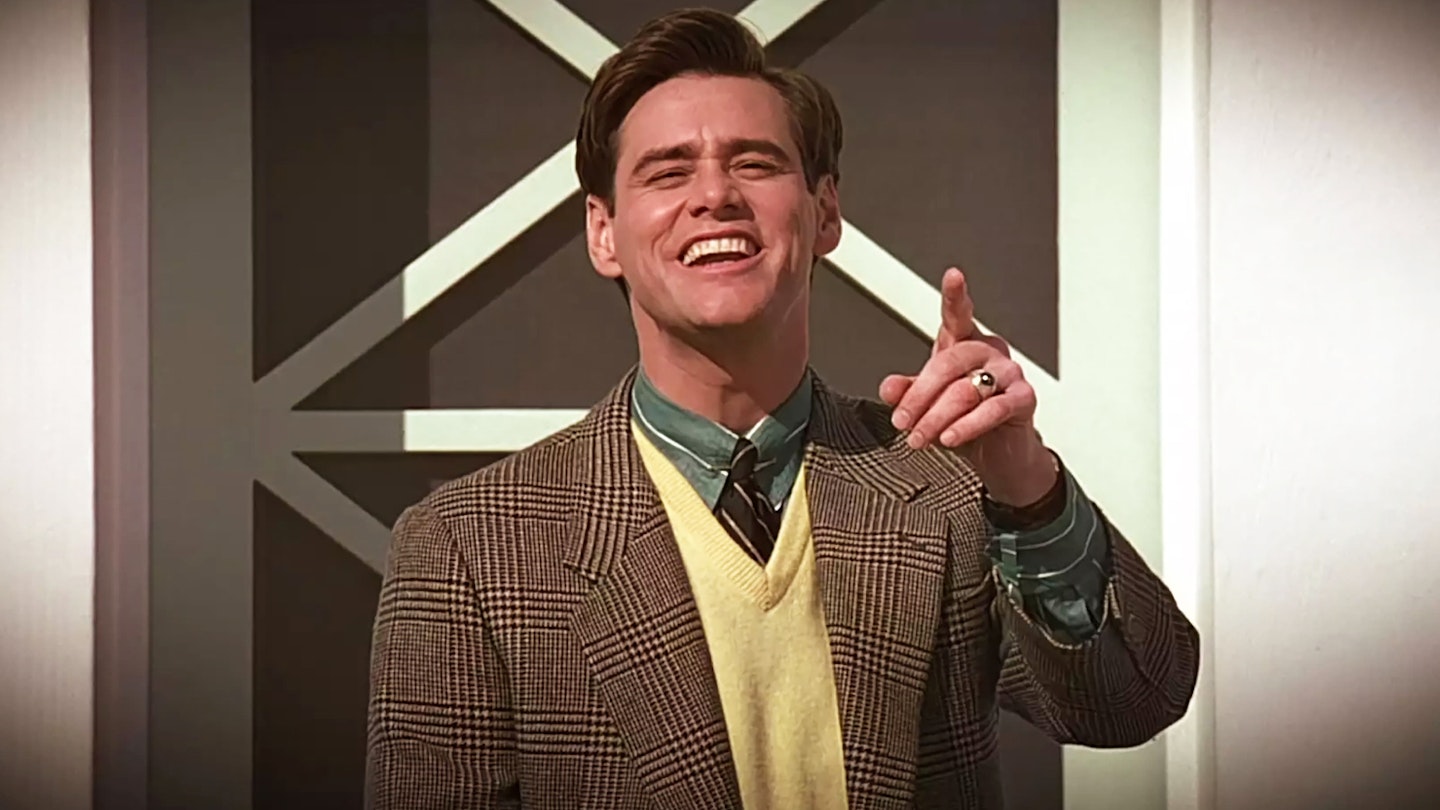

None of it would work nearly as well without Jim Carrey. Weir had already worked wonders with one comedian-turned-proper-actor-actually Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society, and gets a performance out of Carrey which is still pretty astonishing: sunny and kooky, with an undertow of desperation that would, to be fair, make for a properly compelling 24/7 TV show. If ‘The Truman Show’ were on our screens, I’d be clinging to my Truman cushion like those two old ladies. Laura Linney, too, is brilliant as both Truman’s smiling, simpering not-quite-wife Meryl, and the clearly slightly frustrated actor Hannah playing her. She’s trapped on Seahaven too, but she knows something of the world outside, something in her eyes always screaming. No wonder she was scripted to be leaving Truman before his escape attempt. The poor woman needs a break.

But I think underneath the philosophising, The Truman Show might be most affecting as a coming-of-age movie. Truman is knocking on 30 years old (check the front page of The Island Times, which published its first edition about 29 and a half years ago) but in Seahaven he’s a child with not one but two absent fathers – one fell of a boat when he was a boy, the other controls him without ever speaking to him. We see a couple of times that the production staff think of him like a kid too: a producer strokes Truman’s face on the office mega-screen as he sleeps; Christof does the same on his small screen. Walking up those stairs to freedom, Truman eventually leaves his extended adolescence behind and accepts the responsibility of finding meaning for himself.

And that’s where that little T Rex moment comes in. Hollywood was pretty hot for movies about the end of the American century as the ‘90s wound up: Saving Private Ryan, Forrest Gump, Office Space and The Matrix are all wildly different, but they all either looked back at modern America’s founding wartime legends, or pondered the ennui of what it had all come to. The Truman Show presents picket-fenced Americana as the prison. Truman leaves Seahaven behind, and with it a version of the world which had simple rules which made sense. The future of this 20th century boy in the complicated world outside might be uncertain, but at least it’s his.