On release, David Fincher’s The Social Network proved to be an electrifying dramatisation of very recent history – a film that captured a moment in the immediate aftermath of its occurrence, while making clear parallels to the very earliest storytelling traditions in classical tragedies. Over the decade since its arrival – which has brought us Cambridge Analytica, ‘Catfishing’, election scandals, and an entire generation raised on social media – the somewhat-fictionalised Facebook origin story has continued to grow in stature, cementing itself as a landmark 21st Century movie, gaining greater thematic and cultural resonance. All that, and it still thrills thanks to Fincher’s crisp filmmaker, Aaron Sorkin’s whip-smart dialogue, and incredible performances from Jesse Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield, and a scene-stealing Rooney Mara.

As the film turns 10 (don’t forget to send it a birthday message on Facebook!), take a look back at Empire’s original The Social Network feature – going on set for some of its most notable sequences, and speaking to Fincher, Eisenberg, and Garfield during its creation.

———

You cannot ‘friend’ David Fincher. Nor write on his wall, appear in his news feed or ‘like’ his photos. You could poke him, but not virtually. And physically it isn't advisable. In April 2009 the director told Empire, "I don't do Facebook." Seven months later he was making a movie about it.

Except The Social Network isn't really about Facebook, any more than Raging Bull is about boxing. It's about being young, talented and confused; about ambition, invention and betrayal; about gaining the world and maybe losing your soul.

What it is not about, technically, is Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook's co-founder, CEO and president. And the world's youngest-ever billionaire. Jesse Eisenberg refers to his role as “the character of Zuckerberg". Fincher says it's him "as interpreted" by Aaron Sorkin, the screenwriter who admits, "I don't know the real Mark at all." The West Wing creator was brought in to adapt Ben Mezrich's book, The Accidental Billionaires, when it was simply a publishing proposal. Scripter and author wrote concurrently, so while some elements are shared, the correlation is far from precise. Each put their own spin on the story of how Zuckerberg and his closest friend created an online phenomenon – and then spectacularly fell out. In terms of the lead's journey (as projected here, at least), imagine if Michael Corleone had read Wired.

The movie's timing is ironic, given the recent furore surrounding Facebook's attitude to personal privacy. "Mark came out with a comment a few months ago, kind of minimising the idea of privacy," says Sorkin. "I just remember reading it and thinking, 'I don't think you're going to feel that way when the movie comes out.'"

Yet both Zuckerberg and audiences could be surprised by how The Social Network presents its (anti)hero. "If you gave the character" – again, the character – "a clubbed foot and a hunchback you would find him very similar to Richard The Third," says Sorkin. But reading his script, watching it shot and speaking with Fincher suggests a picture that will be, if not sympathetic, then at least a little more empathetic to its central savant than that description suggests. Facebook may have refused to cooperate with the production, but this isn't a movie that's going to demonise either the organisation or its ruler. "A lot of people have differing ideas about Mark Zuckerberg," says Fincher. "But it's an amazing feat to scale something from a college dorm room to 350 million people. The design of it, the coding, is pretty beyond reproach. In that respect, Facebook is an amazing accomplishment."

———

Fincher may not be on Facebook, but he admires its purpose – how it brings people together, how it is “truly about interconnectivity” – as much as the technology. The Social Network is not, though, a multi-million cine-ode to either finding old friends or the joys of Javascript. "There are very few sequences of people actually typing things into a computer! " says Fincher – on a night shoot where we're watching Eisenberg typing things into a computer. Admittedly, it's rather more dramatic than that, as his laptop is snatched away and smashed by a very angry Andrew Garfield.

The young American-British actor is soon to be known to the world as Spider-Man, but for now he's Eduardo Saverin, Zuckerberg's best mate at Harvard, suddenly sensing he's been stitched up. We're in a freshly built building in Pasadena. Originally intended as the new Children's Museum Of Los Angeles – until the organisation filed for bankruptcy – it’s now doubling as the swanky start-up space of what became a $100 billion business. Under strip-lighting, amid desks and cool Cali-kid extras, Garfield has spent 90 minutes in an emotional maelstrom.

Snatching and smashing. Snatching and smashing. Snatching and smashing.

At 12.45am on a Friday in December 2009 – day 34 of the 70-day shoot, take ten of this set-up – Fincher shouts across, "Andrew, disintegrate it! The computer: disintegrate it!" It is a bastard-hard scene: bringing rage and hurt again and again and again. Garfield, in dapper dark suit and perfect US accent, is excellent, but drained. After stumbling over the same word one too many times, he bellows an expletive. Eventually, 25 Apples will be obliterated.

At 5.05am, the various set-ups are exhausted and Garfield is too, when Fincher offers blessed words – "Cut it! Movin' on' – and shakes his hand. Garfield calls out to the crew, "Sorry if I was an asshole!" He wasn't. He was human. That's what Fincher employed him for. "We actually met him about playing Zuckerberg. He has a great kind of warmth, though, and I thought, 'Ah, we wouldn't use any of that!'" says the director, "But we need it for Eduardo: he's sort of the emotional story, of the betrayal." Garfield looks wrung out, but he appreciates Fincher's process ("He has impeccable taste. And he'll only use the things that work. He's brutal – in a very, very positive way").

Sorkin-ese is not for the faint of heart, 'cause you have to drill it and drill it and drill it. – David Fincher

He leaves to change into his own, casual clothes, before returning to crouch behind the camera as it hovers close to Eisenberg. Just before the camera rolls, he leans toward the Zombieland star and hisses, "You're a fucking dick and you betrayed your best fucking friend. Live with that." It's shocking to hear. It certainly helps with the take. And it is evidence both of Garfield's professional generosity and Fincher's nous – for the abuse was at the director's instruction, to help Eisenberg get in the right headspace for the scene.

Eisenberg is superb casting. The alternative names flung around the web were Shia LaBeouf and Michael Cera but, fine actors though they can be, Zuckerberg should not seem either cocky or kooky. He needs the peculiar brand of gauche confidence Eisenberg delivered in The Squid And The Whale. Fincher loved him in that, saw his Social Network audition – shot in New York, posted online – and through, “Holy shit! That's done.”

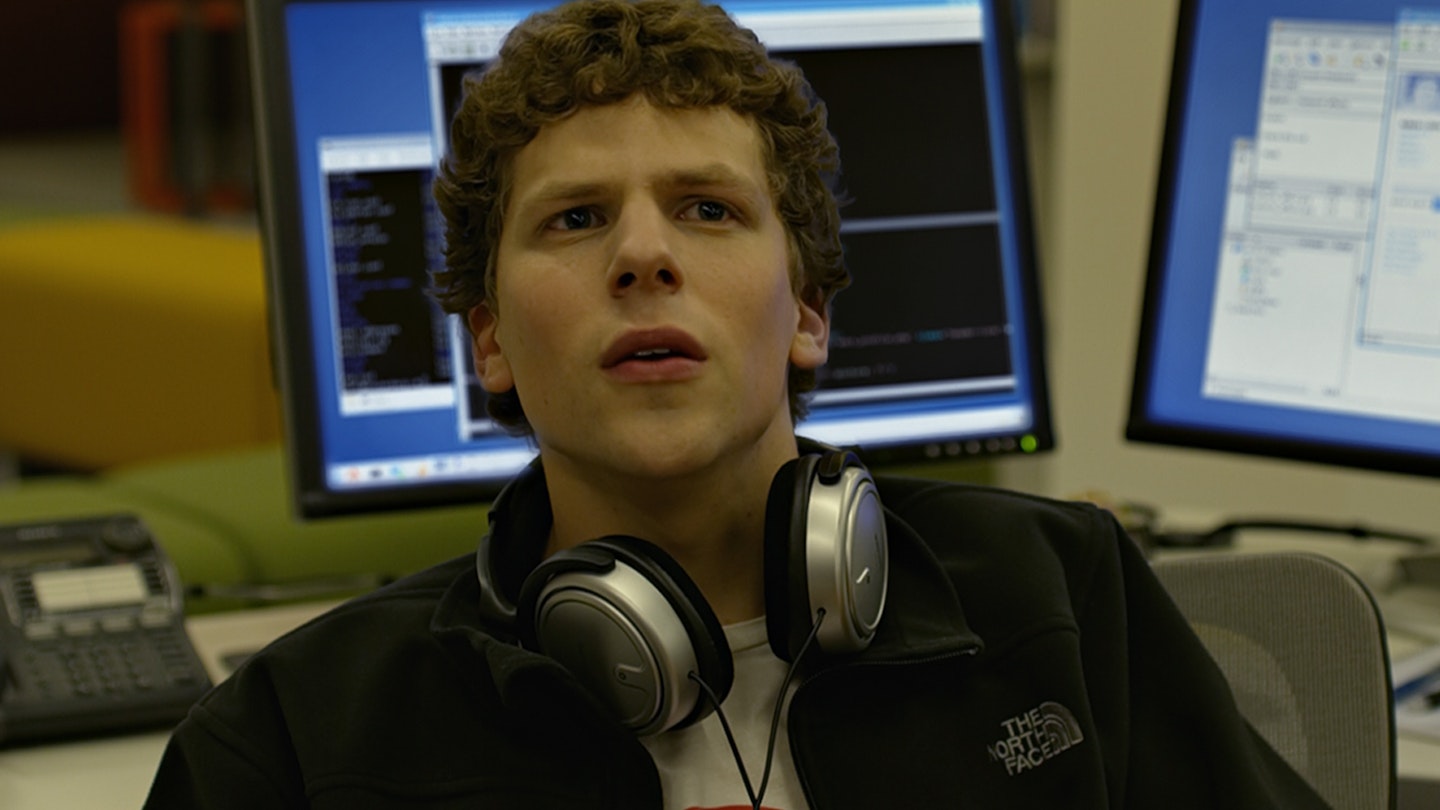

The next night, at the same desk, wearing grey socks with Adidas flip-flops, grey trousers and a North Face fleece, Eisenberg is certainly rocking the e-geek look. It's fascinating to watch his various reactions during Fincher's trademark, legion takes, though easier on the monitor than it is in the flesh – this is a performance about understatement, about the eyes, after all. "The real kind of drama comes out of the feeling that my character sees the site as the primary goal, rather than personal relationships," says Eisenberg. "He gives primary importance to the website and everything else becomes less important, and that's kind of the greatness but also the tragedy of a real visionary." Eisenberg also isn't blind to the irony of the fact that a man who "has difficulty relating interpersonally creates the greatest social networking device in the history of man".

To one side, leaning against a desk, looking – in character – a little too cool for school, is Justin Timberlake. He plays Sean Parker, a man who helped expand Facebook, having co-founded seminal music file-sharing site Napster. As the script has it, he is effectively the computer-programming world's equivalent of, it figures, a pop star.

Fincher saw the platinum-selling singer and fledgling actor in Alpha Dog and on Saturday Night Live and looked to tap his innate ability as a producer, as someone who can perceive and unite talent: something he thought Parker needed. "And I think in the end the thing that became undeniable was I needed somebody who could be Jesse Eisenberg's vision of the guy who has it all."

But if Parker, in the Hollywood incarnation, is a little sly and celebrity-minded, Timberlake in contrast appears humble, taking it seriously. No airs about him, no sense of a superstar flirting with a new hobby. He stays late, after his on-screen scene, to read off-camera lines to Eisenberg. His other half, Jessica Biel, stops by for a while, but there's no entourage. As he says later, "There's one 'alpha' on set and it's David!" He laughs. "When David was happy at the end of the day, I think we were happy."

———

Fincher does seem happy. Perhaps it’s a relief to be back on set after an arduous, post-shoot slog doing effects work, and then an eternal press tour, for The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button. He is still his occasionally barbed, often funny, always frank self ("You can't write down any of this snotty shit I'm saying!" he comments, of his between-takes snarks), but he actually appears to be enjoying himself – something he doesn't usually admit to on set.

Whereas on Button and Fight Club he developed the projects (and on Zodiac he undertook extensive research into the real-life murders), here he was just sent a script, by No Country For Old Men producer Scott Rudin, that he really liked. He did some work on it with Sorkin, but it didn't require years of graft. In budget and days, the production is roughly the equivalent of Seven. It's still demanding – there is no such thing as a simple movie – but perhaps more immediate than his recent shoots; more fun. He even directs one rehearsal while arsing about on a Segway.

"Everybody has been really great. We've only had a couple of people who didn't want to 'play'," he says, drily, referring to how actors cope with his working methods. Certainly it's a challenge for the cast to repeatedly nail the diffuse, specific, witty dialogue for which Sorkin is renowned. "It's exhausting, it's hard, you know?" says Fincher. "Sorkin-ese is not for the faint of heart, 'cause you have to drill it and drill it and drill it. You don’t frame words – you just deliver the paragraph. It's an interesting thing to see 20 year-old faces spouting this stuff. But the big trick of it is to make sure it doesn't end up being somebody aping, you know, [famous 1920s wit] Dorothy Parker."

I've had friends in my life who were part of things I did early on in my career. Sometimes they end bitterly and badly. – David Fincher

Fincher once referred to directing as "collecting moments". Now he refines that description to "collecting behaviour". Because so much of filmmaking is about the script, then about the editing, he wants to really explore while he's actually on set. "I try to spend as much time shooting as I can," he says. "The whole idea about only doing three or four takes... It's like, 'No, what about this? What if this happened, or what if they say it that way?' And, you know, sometimes people are game, sometimes people are like, 'Shit! I don't remember my name!'" ("In between takes I mostly just sing for the crew," jokes Timberlake.)

Clearly, Fincher is a bloke who understands ambition and pressure. After spending most of his twenties as an in-demand music-videos and commercials director, he was entrusted with what was, at the time, the most expensive directorial debut ever: Alien 3. Perhaps that early calamity toughened him forever. Or his upbringing ensured stability. Either way, he has been fortunate enough to remain on an even keel come triumph (Fight Club: the movie) or disaster (Fight Club: the grosses). Maybe he warmed to the script not because of its hit-making topicality, or its wit, but because of its reflection of the reality of being driven.

"I think there was a tangle of relationships that were relatable," he says. "I've had friends in my life who were part of things I did early on in my career and sometimes those relationships fall by the wayside. Sometimes they end bitterly and badly and sometimes there's just an agreed parting of the ways. You know, I've heard enough bad things about myself to know that it's a fucking hard thing to be [in Zuckerberg's position]. I can imagine being 21 and having invented something everybody wants and not wanting to give it up and let it be changed..."

He comes neither to bury Zuckerberg nor praise him. It's just a story about a man with an idea, an idea that would change the world, but not himself. "I related to his passion," he says. "What he wanted to make and how he wanted to make it. And how he wanted to make it to be a certain way."

The final set-up of the night is an insert shot: boxes of business cards being placed on a table. There are 25 takes.

Originally published in Empire Magazine in October 2010.