Most iconic films hinge on one killer central performance that stands above all others. But Jonathan Demme’s adaptation of The Silence Of The Lambs centres on an incredible double-act – Sir Anthony Hopkins’ bone-chilling turn as calculating cannibal Hannibal Lecter, contrasted against Jodie Foster’s compelling turn as FBI rookie Clarice Starling. Both won Oscars for the film, a rare case of the Academy deigning to dignify a genre film with awards (it also won Best Picture, Director, and Adapted Screenplay for screenwriter Ted Tally). If it’s Hannibal who grabbed headlines, it’s Clarice who grounds the film, bringing heart to the horror – one of Jodie Foster’s most enduring performances.

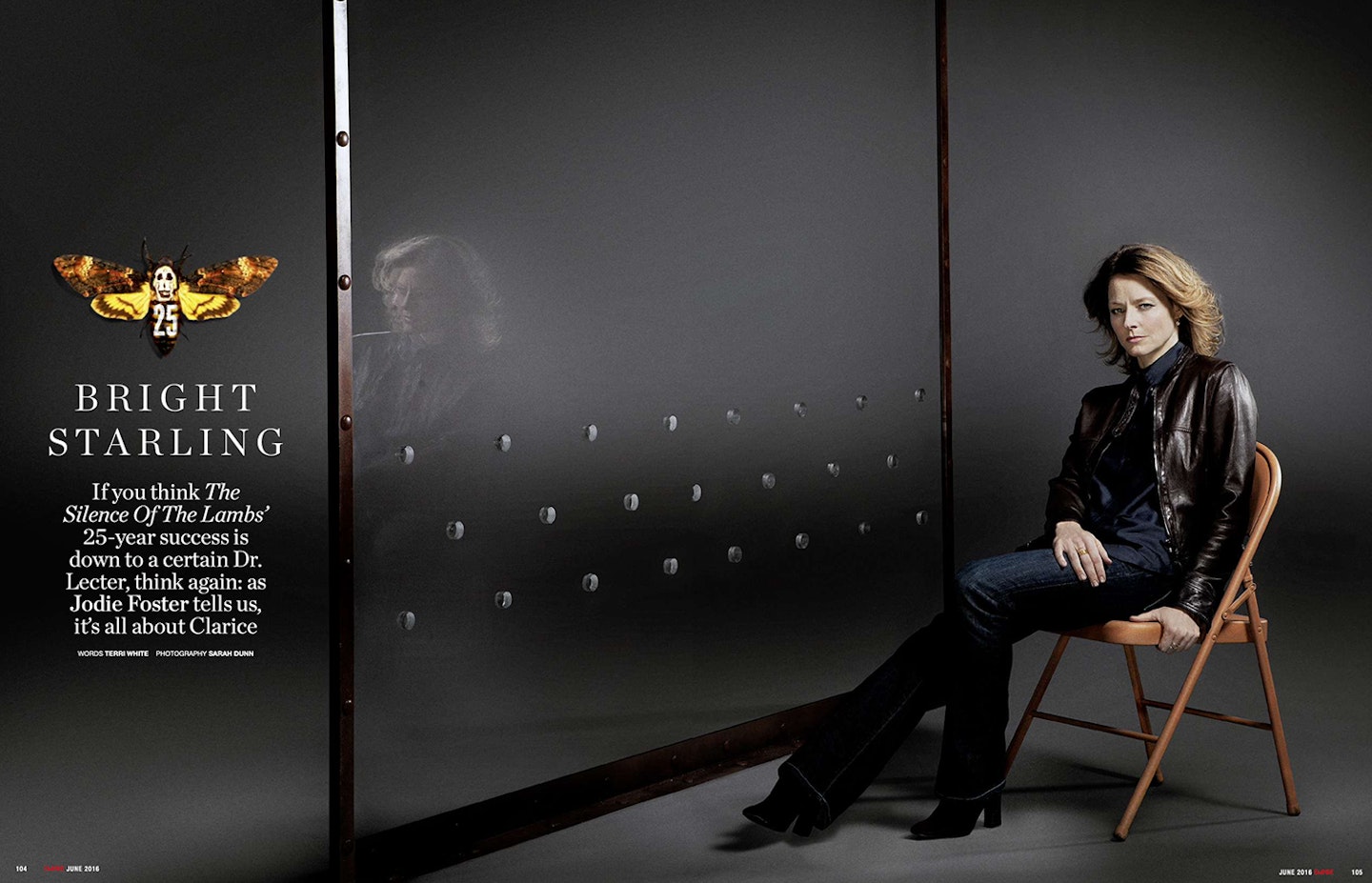

With The Silence Of The Lambs turning 30, Empire presents a 2016 interview with Foster, digging into the enduring appeal and continuing legacy of Clarice Starling – one of the greatest movie characters of all time.

———

Originally published in Empire in June 2016

Indiana Jones, James Bond, Will Kane. As you count down the top ten of the American Film Institute’s 100 Greatest Heroes, all is as you’d imagine it would be. But there, sitting quietly at number six, is a rather different character, a very different hero. Not a chest-beating, gun-toting, whip-wielding protagonist, but a softly spoken intellectual who is slight of frame.

Twenty-five years on from the release of The Silence Of The Lambs, Hannibal Lecter has become a bona fide money-spinning franchise in his own right. Books, films and TV shows have grown up and flourished around the Chianti-sipping serial killer, his “fff fff fff” now more recognisable to the ear than most classic one-liners. And while Anthony Hopkins undoubtedly gave one of the performances of his career in Lambs, the heart of the film belonged – and still belongs – to the woman at number six: Clarice Starling.

———

That character was almost something different entirely. Early proofs of Thomas Harris’ book ended up in the hands of recent Oscar-winner Jodie Foster and, separately, screenwriter Ted Tally. Even though it had bounced around Hollywood with multiple writers declaring it “unadaptable”, both immediately knew they wanted to secure the rights. “Everyone was so distracted by the grimness of the subject matter that they couldn’t see what was right in front of them,” Tally tells Empire. “They couldn’t see the wonderful character story.”

Both were beaten to it by Gene Hackman, who planned to not only write the screenplay, but also produce, direct and star in the film. When he changed his mind on all counts, Orion Pictures picked it up and Tally found himself with the gig he had wanted all along. Jonathan Demme then signed on to direct, with a very specific and rather unexpected Clarice in mind: Michelle Pfeiffer. Foster, however, wasn’t ready to give up without a fight.

“It’s somewhat of an unconscious thing when you’re attracted to something,” she remembers. “You can’t stop thinking about it. You understand how her lips would move, what she’d be wearing.”

Her preoccupation with the character wasn’t a fleeting one and Foster took the bold step of flying to New York to convince Demme that she, in fact, should play Clarice. “I said, ‘I know you have somebody else in mind and I love her and think she’s fantastic and a great actress, but I’d like to be your second choice.’”

Foster moved to pole position when, apparently put off by the darkness of the story, Pfeiffer walked away from the role. But there had been one person who’d been pulling for Foster all along, from when he first “charged through” Harris’ manuscript, right through writing the first draft.

“Intelligence,” says Tally when asked what he saw of Clarice in Jodie (and vice versa). “There are actors who are wonderfully sexy and charming and funny, and they’re not as smart as the character they’re playing. I knew that Jodie was very smart. And I knew that she could project both the vulnerability and the toughness. The things she had been through in her own life would make her sympathetic to the character and make her a champion of women being victimised.”

Winning over Demme may have been tougher, but it wasn’t just circumstance that secured her casting. Foster took, from the book, the belief that this was not only a whole new female protagonist but also a whole new narrative, particularly for this genre. She spoke to him about myth and, specifically, the mythology that sees a young prince being despatched to slay the dragon but who returns when his people need saving.

“When he comes back, he’s figured it out,” she says. “He meets himself along the way and works out his character flaws. He’s changed and heals his people but he’s no longer one of them. That’s such a great traditional myth, but it’s just not one that’s reserved for women. It has always been a man’s coming of age.”

Foster’s take on Clarice elevated not just the character but also the film as a whole. This isn’t simply a ‘cop hunts a serial killer while more women suffer’ slasher story. This is the story of a young woman trying to save other young women and becoming a hero in the process.

'Hannibal is damaged. And he is monstrous and he’s abusive. That character cannot be your main character.' – Jodie Foster

For this shift in the narrative, it was imperative the story be told almost exclusively from Clarice’s point of view, which is where Demme’s signature styles of shooting – both point of view and intense down-the-lens close-ups – became crucial. But not before Tally got to work on the screenplay, presenting it, bar Lecter’s escape and Catherine Martin’s abduction, entirely from Clarice’s perspective. This was a significant shift from the book.

“This was the most important decision I had to make in the adaptation,” Tally says. “Everything sprang from that. The book had multiple points of view and went inside Lecter’s head, (FBI agent-in-charge Jack) Crawford’s head, Jame Gumb’s head. I thought, ‘it’s her story and I want the audience to, if possible, not know more than she knows. To find out things as she discovers them herself.’ She’s their representative, she’s taking them on this journey with her.”

In that sense, Foster and Starling were the audience. She was the guiding morality, the face of normality and decency in direct contrast with so much darkness and brutality, and particularly in contrast with Lecter. This, to Foster, is the key to Clarice’s position at the centre of the film.

“Hannibal is damaged. And he is monstrous and he’s abusive. He’s lashing out and to him that’s delicious — he feeds upon that hurt, because that’s the way he knows how to connect with power. That character cannot be your main character. You need to understand him or come to him through someone whose feet are grounded and is grappling with human problems.”

That relationship with Lecter however, is not merely one of good versus evil, of right versus wrong. She sees him as not simply a monster but recognises, and to some extent respects, his intelligence as well. Crucially, he is the only man in the film to treat Clarice as an equal, to not patronise, condescend or make judgements upon her based on gender. The audience immediately understand the position she occupies in her world when, getting into the elevator at Quantico in one of the establishing early scenes, a circle of men tower over her as she stands firmly in the centre.

Much of the dynamic and tension with Lecter was based on the real relationship between Foster and Anthony Hopkins, who didn’t have a chance to get to know one another before shooting began, so – apart from a table read in Orion’s New York headquarters – their first interaction was shooting either side of the glass. “We weren’t really comfortable with each other,” shares Foster. “Somewhere towards the end, I was having a tuna fish sandwich and he was sitting across from me. It was sort of like the first time that we had talked. I put my arms around him and he put his arms around me and he said, ‘I was scared of you,’ and I said, ‘I was scared of you!’”

Though both gave Oscar-winning performances, Tally is certain of whose movie it ultimately was: “When people kept wanting to talk about Hannibal, I said, ‘He’s the sizzle, but she’s the steak’. She’s what it’s all about. He’s a supporting character, in effect.”

———

Though undoubtedly the central protagonist, Clarice isn’t merely a hero without complication. She is vulnerable, intelligent and strong, but also fiercely and unashamedly ambitious, a rare quality in a female character that audiences are meant to root for. During her very first visit to Lecter, Clarice is quick to use her femininity to manipulate Dr. Frederick Chilton (Anthony Heald) into allowing her to see Lecter alone, responding coyly with, “I would have missed the pleasure of your company, sir,” when he questions why she didn’t make her request earlier, when they were in his office.

Similarly, it’s been suggested that Clarice is simply bait for Lecter and spends the movie being manipulated by him, but Foster sees this as very much a conscious decision on her part. “This is a character that’s restrained and reserved and calculated,” she says. “She’s wilfully being used by him — she’s so ambitious that she’s willing to let it happen.”

This ambition is ultimately what leads Clarice to Buffalo Bill: not using physical strength and brute force but by reading the killer through the eyes of his victims, through empathy. Foster and Tally see this as being due in large part to Clarice’s own history (“Well, Clarice – have the lambs stopped screaming?”), but crucially, though traumatic, hers is not filled with the conventional forms of trauma most female characters were handed by writers.

“Her past is not about being raped or having her father abuse her or any number of tropes that have always been female motivations on film,” asserts Foster. “You keep waiting for that terrible awful memory – you know, ‘that’s why Clarice is so singular because she actually is a victim’. When, in fact, it’s something simple, that everyone can relate to. It’s that love for her father. It’s delicate, and their relationship was delicate, and the importance and significance of it is delicate.”

Coming o the back of her role as rape victim Sarah Tobias in The Accused, Foster was determined to play an entirely different type of character and, more importantly, an entirely different type of woman. Many people around her thought this was the wrong direction after picking up a gold statue. They were surprised she wasn’t, as she puts it, plumping for a more “flashy, flamboyant character”. For Foster, though, she craved this shift away from victimhood.

“There really was a pattern where I just kept playing women who were victims,” she says. “There was something about this shift to a woman that could identify with victims but was destined to be the person who saves them because she knows them so well. In a weird way it mirrored how I saw myself and what I wanted to do with my work.”

———

Foster’s gamble (if it could ever really be considered such a thing) paid off and Clarice was something genuinely revolutionary in film at the time – the late ‘80s, the start of the ‘90s – and Foster, Tally and Demme all knew they’d created something and someone that had never been seen on screen before. Which made it all the more surprising when Foster didn’t reprise the role for the sequel.

She cites the sheer amount of time it took Harris to write the next book as the reason, something she says surprised them all (Hannibal wasn’t published until 1999). “I think we all thought we’d be joining together again,” she laments. “We didn’t realise at the time that that would be it.”

Yet there is surely solace in the knowledge that the impact of this character, as portrayed in The Silence Of The Lambs, has in no way lessened and is still felt through other films, and through female characters as a whole. Foster tells Empire a story about taking her kids – now old enough – to see The Silence Of The Lambs at a movie theatre in Los Angeles and her joy that they wanted to talk about it afterwards. It had stood the test of time. Clarice had stood the test of time. She still resonated.

Suddenly number six feels like it doesn’t do her justice.