As a filmmaker, Terence Vance Gilliam’s career has been, if nothing else, eventful. He’s grappled with studios more publicly than almost anyone else, seen disaster strike nearly every film he works on, and has constantly pursued his appropriately quixotic task of dragging Don Quixote to the big screen. With all this drama, disaster and success, it’s easy to forget he was once one sixth of Monty Python. He’ll be joining the rest of the surviving troupe onstage at London’s O2 later in 2014, but not before the release of his latest film, The Zero Theorem.

Notorious for grappling with studios over money and his creative vision, Gilliam has taken matters into his own hands when faced with implacable execs. In 1985, he placed a full-page ad in Variety after Universal bigwig Sidney Sheinberg refused to release his version of Brazil. It read simply, “Dear Sid Sheinberg, when are you going to release my film, ‘BRAZIL’? Terry Gilliam.” After some illicit screenings and a slew of awards, the film saw the light of day in the US. Since then, Gilliam has made the most of advertising in his own, unconventional way. Upset at the short shrift Tideland was given by the studio, he took to the streets in 2006, accompanied by a cup for spare change and a cardboard sign, funded by the Garofalo Pasta Company. According to Gilliam, “the only stipulations were the film had to be made in Naples and nobody gets killed in it. I did exactly what I wanted to do.”

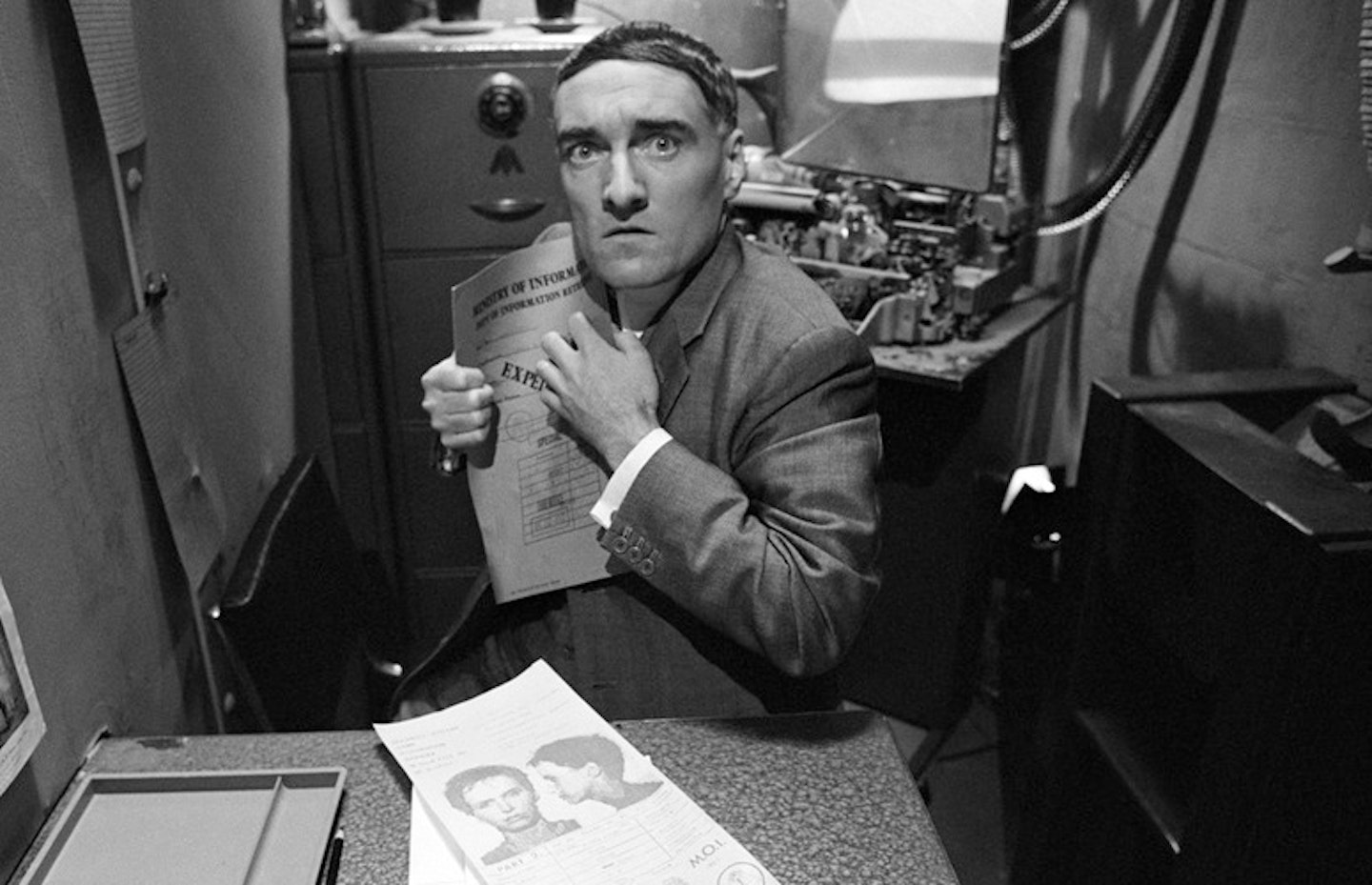

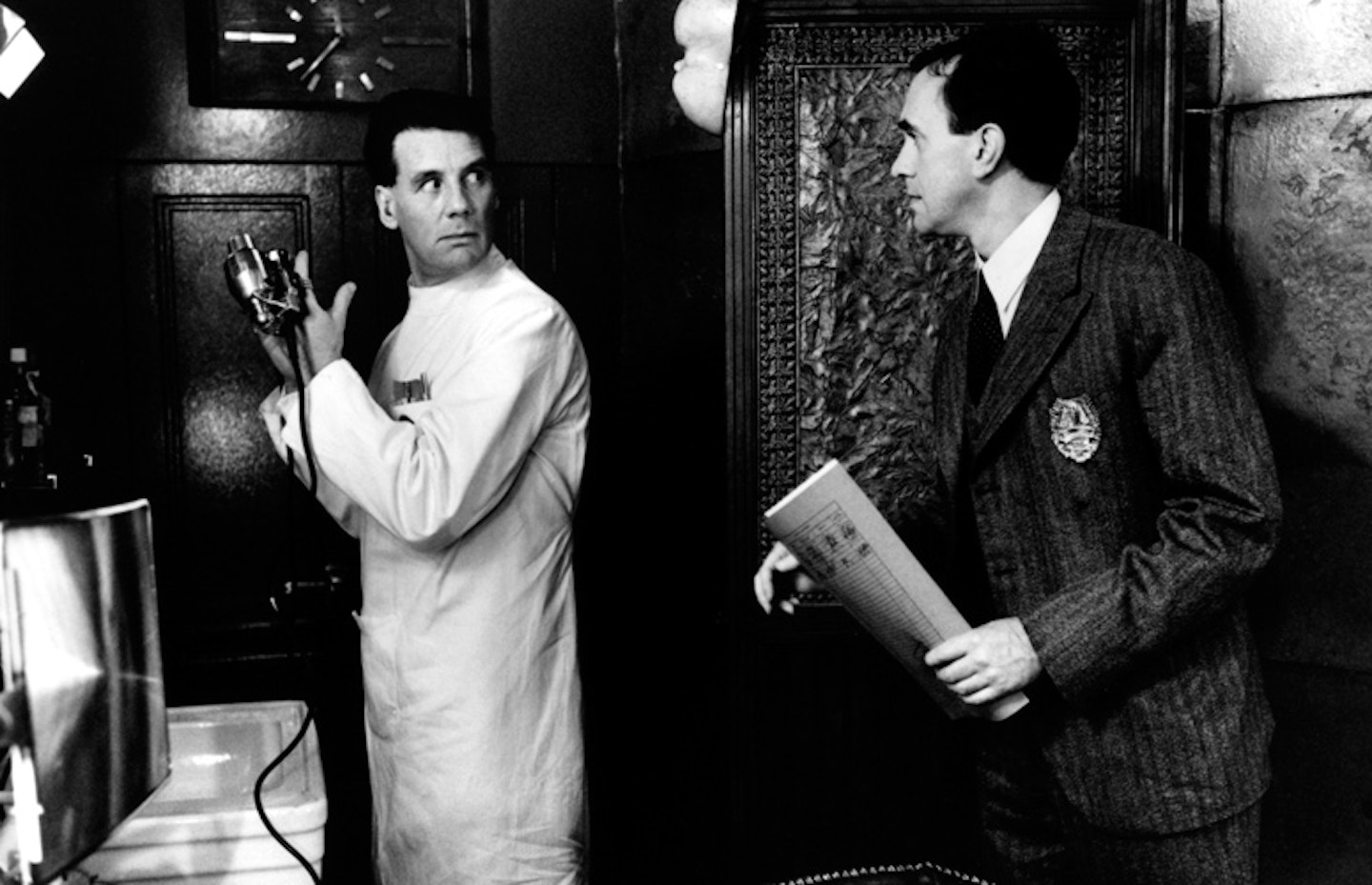

From the swashbuckling accountants of The Crimson Permanent Assurance to the implacable panel of bearded doctors in The Zero Theorem, Gilliam has always had a visceral hatred of bureaucracy. Anyone who’s seen any of his films will be familiar with the image of a bureaucrat’s face looming large in a wide-angle frame, frustrating the hero’s cause. The most significant example of the director’s antipathy, though, is Brazil; here, the entire plot revolves around a bureaucratic error which ends up with Archibald Buttle being wrongly killed. For Gilliam, this is typical: it’s not so much that he objects to bureaucracy in theory, but instead that it’s run by flawed human beings in a chaotic world. Huge, often faceless, institutions blunder around, making enormous mistakes that ruin lives. The Ministry of Information in Brazil, the police, mental health services and airport security in Twelve Monkeys, Management in The Zero Theorem – all these monoliths represent his films’ real enemy.

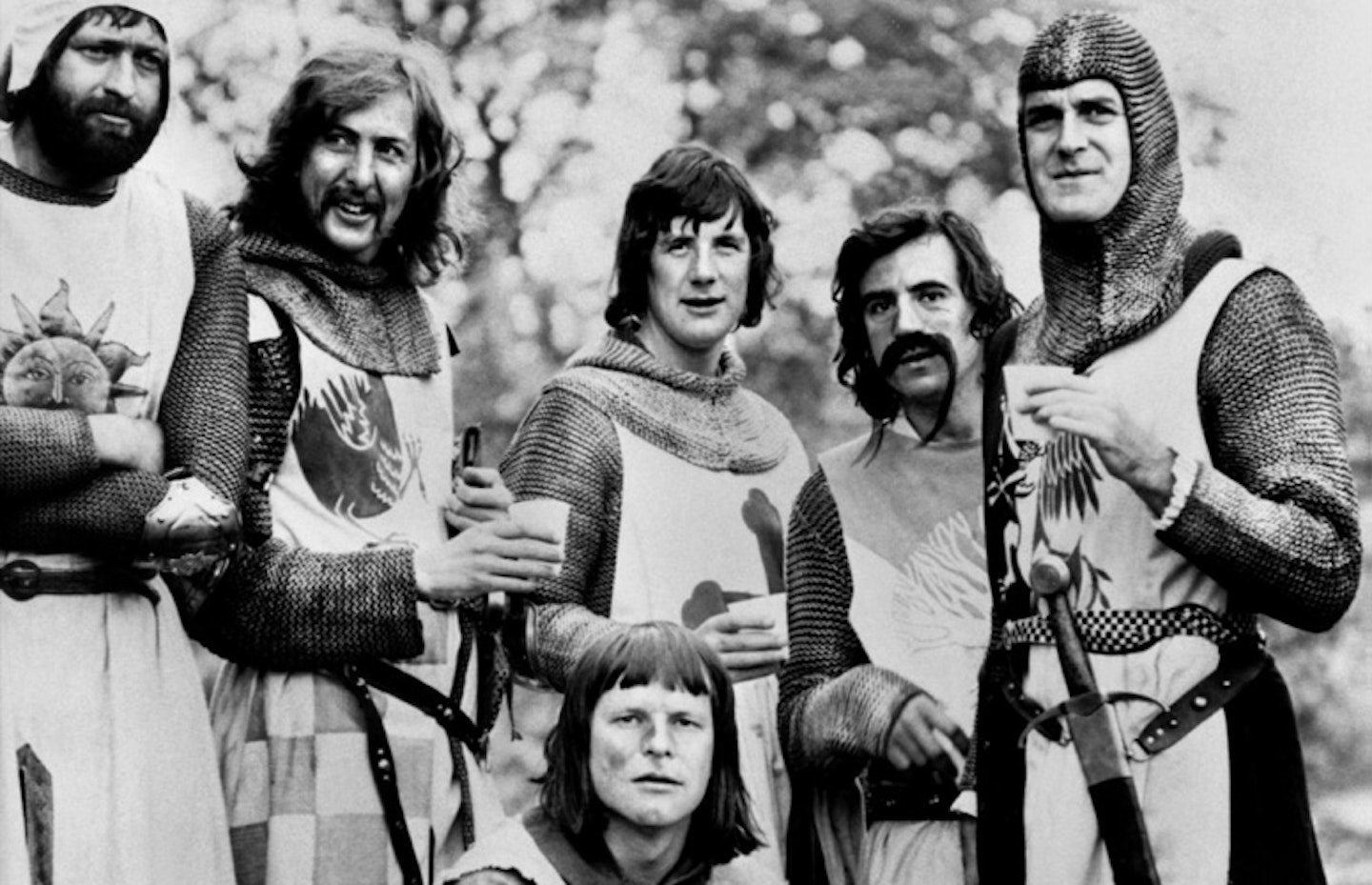

As part of the Monty Python troupe, Gilliam never went in for many starring roles. Instead, he got comfortable taking the weirder, more grotesque parts on offer: from Patsy in Monty Python And The Holy Grail onwards, he’s leant his distinctive visage to a wide variety of tiny roles. Usually these were in his own films, such as “Irritating Singer Inside Fish” in The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen, or an uncredited smoker in Brazil. In 2013, though, Gilliam revealed on Facebook that he’d been cast in “a small but vital role” in the Wachowskis' Jupiter Ascending. “Small” appears to be right: it took just one day to film. To hear the man himself talk about his cameo in John Landis's Spies Like Us, listen to our Empire Podcast special with him here.

This age-old technique of tilting the camera to one side has long been shorthand for madness or terror. It’s utilised in everything from The Third Man to Adam West’s Batman, and was perhaps most notoriously (mis)used in the John Travolta mega-flop, Battlefield Earth. Yet Gilliam is one of the technique’s greatest proponents. Particularly in his sci-fi outings, there are so many wonky cameras that you could be forgiven for thinking someone needs to buy Terry a new tripod. Since 1997, though, he’s found someone who shares his predilection for imbalance: cinematographer Nicola Pecorini (see “P”). They first collaborated on Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas, and are proudly continuing their Dutch look in The Zero Theorem, echoing the disorientated, possibly damaged mental state of Christoph Waltz’s Qohen Leth.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Gilliam tends to find an editor and stick with them. His most frequent collaborators have been Mick Audsley (Twelve Monkeys, The Imaginarium Of Doctor Parnassus, The Wholly Family, The Zero Theorem), Lesley Walker (The Fisher King, Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas, The Brothers Grimm, Tideland) and Julian Doyle (Time Bandits, Brazil and two Monty Python films). In the case of Brazil, the editing process was hijacked by the studio to manufacture a happy ending. It was only with the aid of a Variety ad (see “A”) that the film avoided scissor-happy executives. A good thing too – with his films’ unique rhythms and often uncompromising endings, Gilliam’s spirit is often found in the editing room. This is particularly true of The Zero Theorem, which had a very fast pre-production and shooting schedule; for Gilliam, “the editing was the really creative moment”.

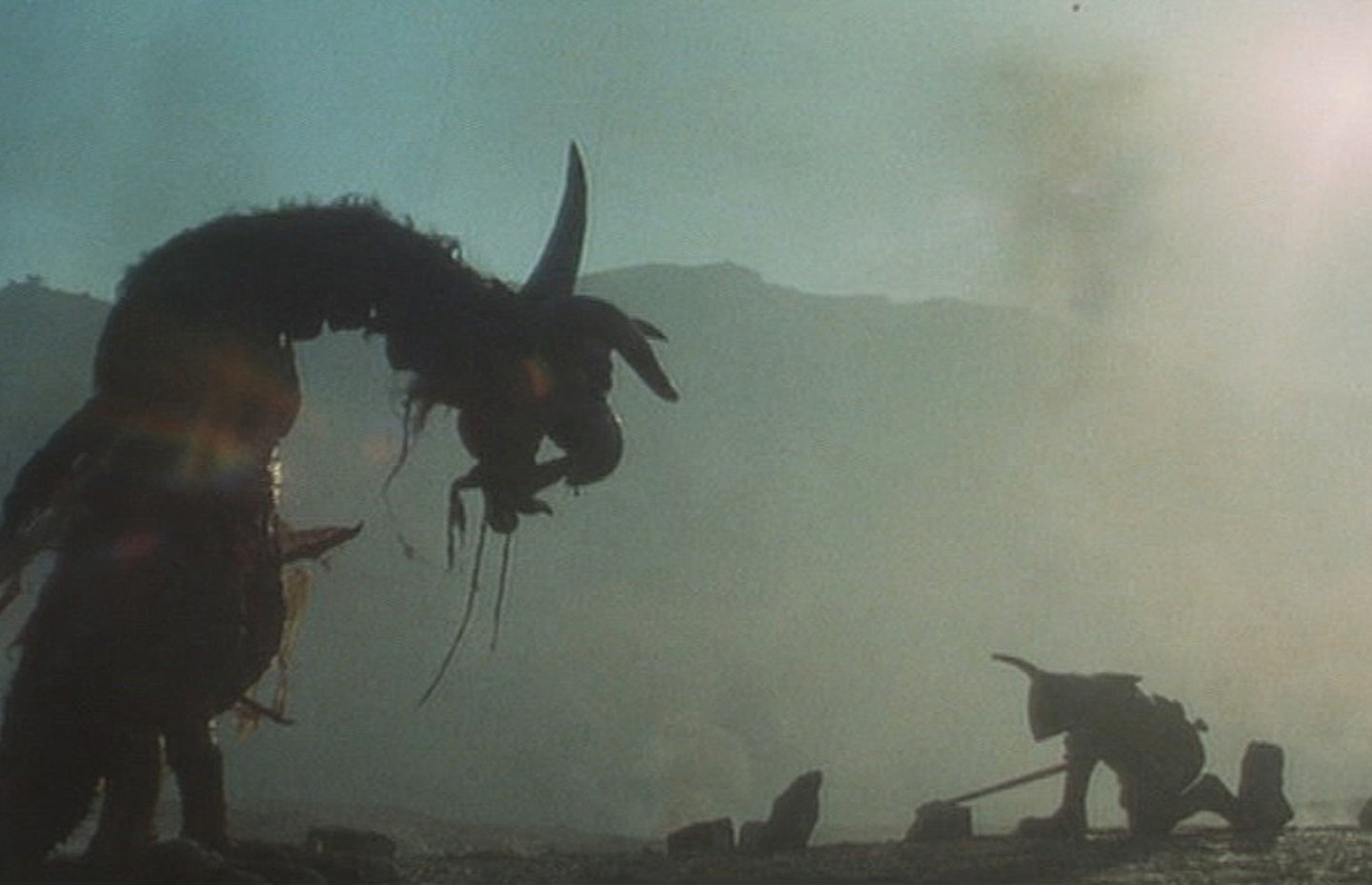

It wouldn’t be a Gilliam film without a trippy fantasy sequence. Whether it’s an angelic Jonathan Pryce battling a scary samurai, Christoph Waltz floating naked towards a black hole, or Jodelle Ferland with her creepy doll heads, the director never restrains his surreal imagination. Anyone familiar with his Python animations (and who isn’t?) will know to expect the unexpected in anything he turns his hand to. It’s not all from his own twisted mind, though: Gilliam’s first solo directing effort, Jabberwocky, was ripped from the strange pages of Lewis Carroll, while The Brothers Grimm was taken from, er... the Brothers Grimm. Still, Gilliam’s relentless ingenuity has also on occasion saved his films: when Heath Ledger died halfway through filming Parnassus, only Gilliam could envision three different actors replacing him and have it make complete sense.

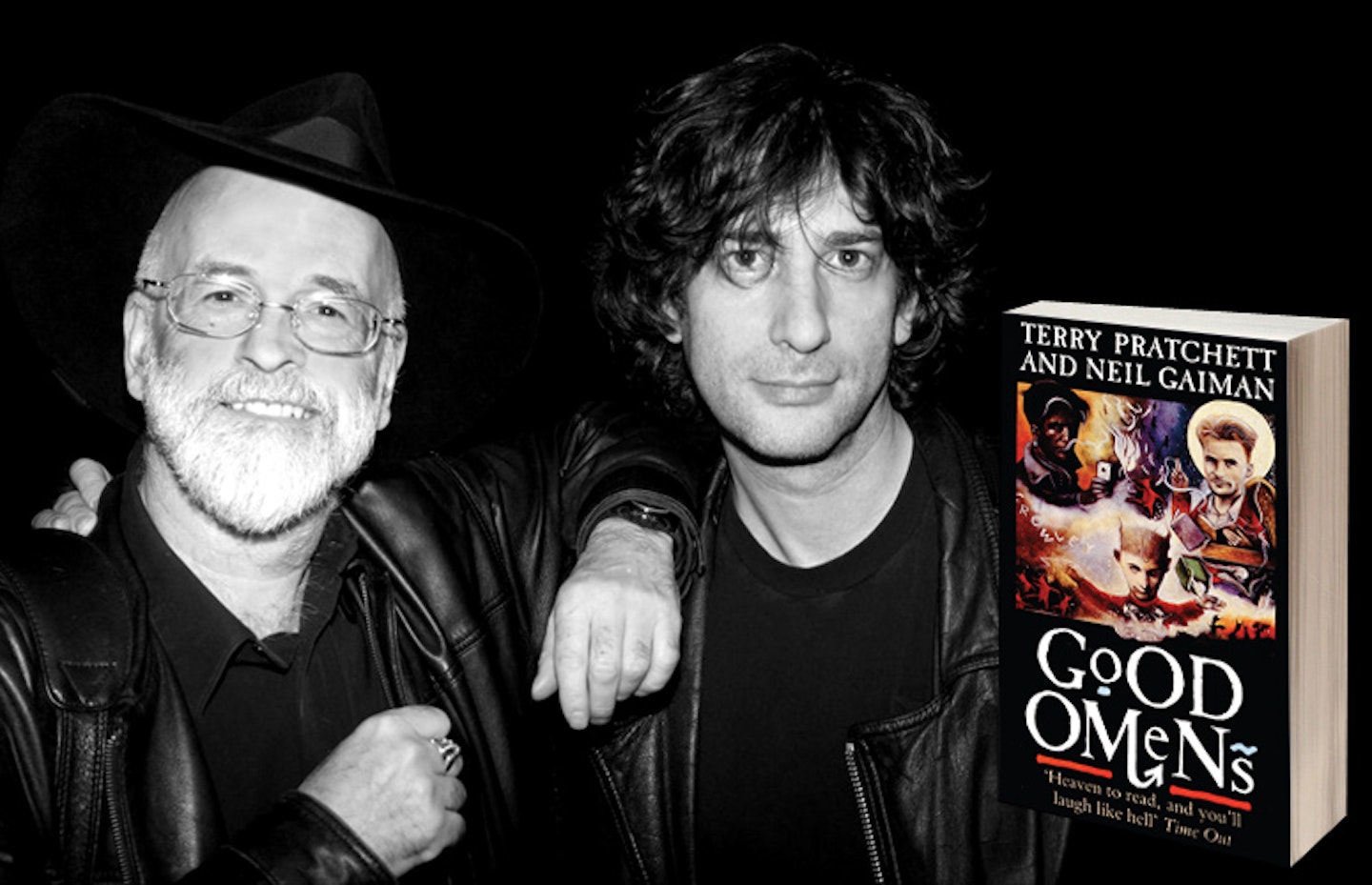

It seems like a match made in heaven: Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman’s hilarious 1990 novel married with Terry Gilliam’s anarchic, astute eye. A script was floated around, and Gilliam himself said he was excited to do it. But, as always seems to be the way, there were money issues. At various points over the last decade, the director has expressed interest in the project. In 2008, he told Empire he was still keen: “I’m the only one who can make it, ‘cos that’s what Neil and Terry have said. I’m the only one... It’s such a wonderful book. And I think our script is pretty good, too. We did quite a few changes. We weren’t as respectful as we ought to have been. But Neil’s happy with it!” There have also been rumblings from Rhianna Pratchett that we may yet see a TV version of the novel (presumably Gilliam-less). Still, we live in hope...

It’s fair to say that Terry Gilliam and Hollywood aren’t the best of friends. In the great Twelve Monkeys documentary, The Hamster Factor, he’s baffled to hear himself described by the media as a Hollywood director: “Hollywood? I’ve now become a Hollywood director. There’s no stopping these folks...”. From Brazil onwards, each film seemed to have its own little drama, as Gilliam tussled with executives over his vision. He fought Universal over Brazil’s final cut, saw Baron Munchausen’s costs explode (at the expense of the marketing budget), and battled with the suits over Tideland’s tiny US release (and a stealthily rejigged aspect ratio on the DVD). But surely his biggest, most dangerous opponent came in the form of one Harvey Weinstein (see “W”).

A Gilliam set is a dangerous place to be. After working on Munchausen, former Python Eric Idle gave some sage advice about the director’s films: “You don’t ever be in them. Go and see them by all means – but to be in them, fucking madness!” On that very film, a nine-year-old Sarah Polley (now best known for Stories We Tell) found the experience “physically grueling and unsafe”. On the notorious – and abandoned – The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, lead actor Jean Rochefort (then 70 years old) injured himself riding a horse and was flown back to Paris with a double herniated disc. And even the great man himself hasn’t escaped without battle scars. As he revealed to Wired, he broke his back on the set of Doctor Parnassus when a bus backed into him. “Vertebrae [were] cracked, muscles were ripped to shreds... I didn’t sue the company, I hate that sort of thing, so they gave me physical therapy and all that stuff, plus they gave me free transport, which was very useful to finish the film up.”

Although he’d co-directed Monty Python And The Holy Grail with Terry Jones, Jabberwocky was his first solo outing behind the camera. Gilliam was entranced by the slithy toves and frumious Bandersnatches of Lewis Carroll’s original nonsense verse, and combined this with plenty of Pythonesque humour. In fact, the Python influences are so strong that not only does it star Michael Palin (and feature a Terry Jones cameo), it was actually marketed in America and beyond as Monty Python’s Jabberwocky. Nonetheless, with its loathing of bureaucracy, grotesque practical effects, and sense of joyful chaos, it is unmistakably Gilliam’s brainchild. After all, when the Jabberwocky eventually falls to its death (spoiler!), it was in reality just the actor genuinely tripping over.

Given his apparent preoccupation with silly English kniggits, it’s fairly surprising Mr. Gilliam has never done a full-on swords and suits of armour epic. As it stands, though, we have knights in Jabberwocky, Time Bandits, Brazil, The Fisher King, and of course The Holy Grail. Oh, and let’s not forget the eponymous Spaniard in The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. As played by Jean Rochefort, Don Quixote is a faithful, fleshed out version of the famous Picasso silhouette, with his cobbled together armour and trusty horse. In fact, Cervantes’ original novel is hugely preoccupied with themes of chivalry and knighthood, so Gilliam’s obsession shouldn’t be too surprising.

In 2008, The Imaginarium Of Doctor Parnassus inadvertently became a film everyone had heard of, when Heath Ledger died midway through filming. He had been a key reason the film got financed in the first place, and his performance was in the process of becoming something truly special. As Gilliam reflected afterwards in an obituary, “He just kept getting better and better. He was fearless... he was improvising all the time and it was better than what we had written. I don’t normally encourage that kind of improvisation, but in a sense I felt Heath was writing this film.” However, Gilliam and Ledger’s partnership wasn’t new – they first met in 2001 in preparation for The Brothers Grimm, and Ledger noted that since then they had “developed a really personal close friendship and trust. And I’d really do anything. I’d cut carrots and serve the catering on a Gilliam film.” As Gilliam later recalled, “When he died, it was as if half of the world had collapsed.”

Terry Gilliam doesn’t always write his own scripts, but when he does, it’s often done hand-in-hand with one Charles McKeown. The two met on the set of Life Of Brian back in 1978 (in which McKeown was an actor), and went on to co-write Brazil, The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen and The Imaginarium Of Doctor Parnassus. However, their collaboration doesn’t end there – he’s also co-written some of Gilliam’s famous unmade films. They worked together on a Watchmen script, which McKeown described as “frustrating” (see “T”), a Time Bandits sequel (as well as two mooted TV spin-offs), and on the never-ending quest to drag Quixote to the big screen.

This is a slightly weird one, in that it’s not actually very weird. This Nike campaign featured a whole host of footballing legends, and originally appeared during the 2002 FIFA World Cup. Set to a remix of Elvis's 'A Little Less Conversation' and supposedly costing upwards of $100 million, the adverts don’t exactly scream Gilliam. They’re stylish, for sure, but there’s nary a Dutch angle or medieval knight to be seen, which makes sense when you discover that Gilliam didn't actually direct all that much of it, leaving it to the bigger football fans on set to organise the shots. Still, we do get Eric Cantona strutting around with a cane and being eccentric, which is pretty Gilliam in its own unique way.

Gilliam’s difficulties getting films financed are the stuff of legend, so he has occasionally embraced the stage instead. In 2011, though, he made the surprising decision to direct an opera. By Gilliam’s own admission, this wasn’t exactly his speciality, but the themes of Berlioz’s The Damnation Of Faust do seem particularly well suited to the director. Looking back on Brazil and his tussle with executives, he calls that “a Faustian moment. I could have done the deal, given the studio a happy ending. It’s my basic nightmare... When I watch my friends in Hollywood who have become more and more successful, I actually feel they have lost their soul.” And soulless Gilliam’s Faust was not. It garnered rave reviews at the ENO’s Coliseum, and has since moved overseas to Ghent and Antwerp.

Python, Monty might make a more obvious entry under “P”, but in his solo work of the last two decades, there are few more important collaborators for Gilliam than cinematographer Nicola Pecorini. The Italian DP has worked on every one of the director’s films since Fear And Loathing, as well as abandoned projects like Good Omens and Don Quixote. He’s seen first hand the frustration of financing and development that Gilliam always faces: “Terry’s scripts seem to be always too difficult to grasp, and to be understood and embraced by the people with the money.” He’s a fierce defender of Gilliam’s vision, and the two have a close working relationship, as Gilliam told Coming Soon: “Our game is basically that I’m Don Quixote and he’s Sancho Panza. Nicola is incredible. He’s outspoken. He says what he thinks. He is dangerous and we get on. We just get on.”

Ah, Don Quixote. Gilliam’s long-gestating script for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote has been off and on so many times it’s difficult to count. The closest it came was in 2000, when filming actually got underway with Jean Rochefort and Johnny Depp. However, thanks to military planes, flash floods, and Rochefort getting badly injured, the whole shoot was scrapped – all brilliantly captured in the documentary Lost In La Mancha. Apparently unable to take a hint, Gilliam has chased his dream again and again. Things got close in 2008, with Robert Duvall and Ewan McGregor attached, but funding had collapsed by 2010. Unbelievably, Gilliam is as determined as ever, and in January 2014, he posted new concept art of Quixote tilting at windmills, saying, “Dreams of Don Quixote have begun again. Dave Warren has started doodling. Will we get the old bastard back on his horse this year? Human sacrifices welcomed. Stay tuned.”

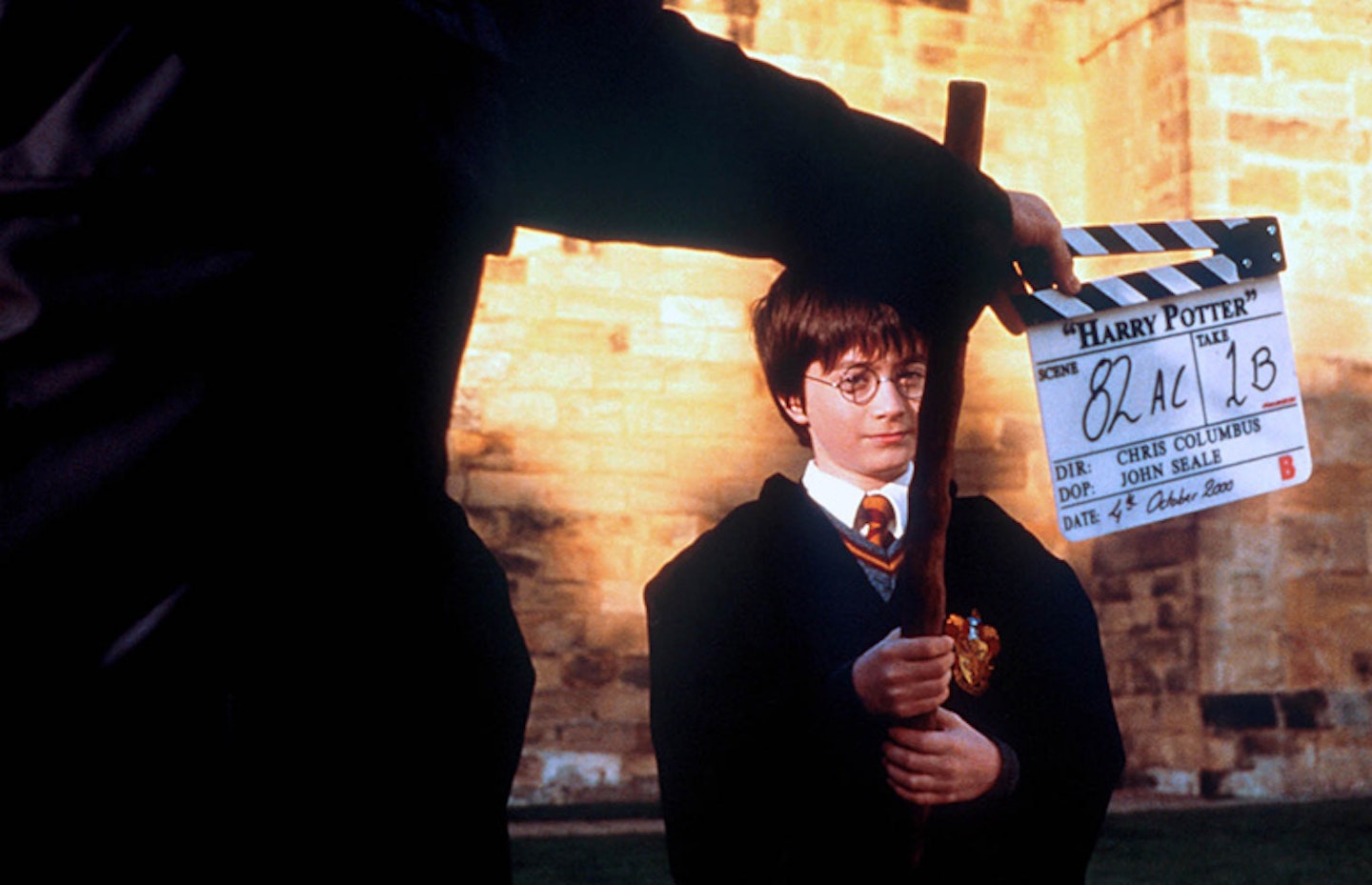

The Harry Potter author has always been a fan of Gilliam’s work, and when a film adaptation of her Hogwarts adventures was first contemplated, she suggested the former Python would be the perfect helmsman. Alas, Warner Bros. soon balked, and considered the director of Home Alone 2 and Bicentennial Man to be a better fit. Needless to say, Gilliam disagreed: “I was the perfect guy to do Harry Potter. I remember leaving the meeting, getting in my car, and driving for about two hours along Mulholland Drive just so angry. I mean, Chris Columbus’ versions are terrible. Just dull. Pedestrian.” He looked more kindly on Alfonso Cuarón’s Prisoner Of Azkaban, but nonetheless ruled out ever venturing into Hogwarts himself.

The Oscar and Tony-winning playwright, screenwriter and novelist has collaborated with Terry Gilliam and Charles McKeown, helping with the script for Brazil. He’s best known for his philosophical and hyper-literary work, including Rosencrantz And Guildenstern Are Dead, Arcadia and (most famously) Shakespeare In Love, but has also leant his hand to the third instalment of Indiana Jones and the Star Wars prequels. As Gilliam recalls, Stoppard introduced some key plot points into Brazil, as well as some unwanted neatness: “He was making certain sense out of some of the things like ‘Buttle/Tuttle,’ because those people didn’t have similar names at the beginning. So it starts coalescing and at the end of his period, I started working with Charles McKeown and started making a bit of a mess of the neatness that Tom had brought to the film, and then tried to make it a bit more murky, to get us back into the mire.”

It’s well known that Terry Gilliam got his start in television. He first worked purely as an animator on the Python precursor, Do Not Adjust Your Set, then on Monty Python proper. Before long, he was being used as an occasional actor and was promoted from animator to a fully-fledged member of the surrealist troupe. Since then, Gilliam has tended to avoid television, but he has still had the occasional brush with the box. After developing Watchmen with Charles McKeown and having it come to naught, [Gilliam later concluded TV would be the way forward](http://uk.ign.com/articles/2000/11/17/interview-with-terry-gilliam-part-3-of-4t-3-of-4): “a five-hour miniseries is what I think Watchmen should be.” There were also two mooted TV specials of Time Bandits, which never came about. Nonetheless, another of Gilliam’s films has been adapted for television – albeit without his involvement. A spin-off TV pilot of Twelve Monkeys has been produced for Syfy, which the director told ScreenDaily "doesn’t have anything to do with me and no-one has contacted me... It’s a very dumb idea. That’s what I think.”

As you might be able to tell from the accent, Gilliam wasn’t born in Britain. Originally from Minneapolis, he moved to the UK in the late 1960s and has pretty much stayed put ever since. In a fascinating conversation with novelist Salman Rushdie (worth reading in full here), Gilliam revealed how his genuine anger at America led to his departure: “I became terrified that I was going to be a full-time, bomb-throwing terrorist if I stayed, because it was the beginning of really bad times in America... I got more and more angry and I just felt, ‘I’ve got to get out of here.’ I’m a better cartoonist than I am a bomb maker. That’s why so much of the US is still standing.” In 1968, he obtained British citizenship, and in 2006 he decided to renounce his American citizenship, motivated both by a dislike of the Bush administration and by tax reasons.

In 2011, Gilliam revealed he was working on an adaptation of Paul Auster’s novel, Mr. Vertigo: “I’m actually working on a script of it at the moment. Doesn’t mean it will be a film; but I’m working on a script.” It may yet be one to add to the looming mountain of Gilliam’s unfinished projects, but there is reason to be somewhat hopeful. Auster is no stranger to the silver screen, having written several screenplays and even directed a film: The Inner Life Of Martin Frost. This particular novel, though, is more child-friendly than much of his work, and has Gilliam stamped all over it: it follows Walt the Wonder Boy reflecting on his youth, when he learnt how to levitate and was part of a travelling show run by the mysterious Master Yehudi. So, combine the flying sequences of Brazil with the travelling theatre of Doctor Parnassus, and you might be getting close...

Of all Terry Gilliam’s well-publicised spats with movie executives, his feud with the Weinstein brothers is undoubtedly the best known and most personal. In 2003, the Weinsteins took on the job of co-financing and distributing Gilliam’s The Brothers Grimm – but their involvement didn’t end there. They got stuck in, frequently overruling Gilliam and literally imposing their own vision: after six weeks, they fired Gilliam’s regular cinematographer Nicola Pecorini (see “P”) and replaced him with Newton Thomas Sigel. Production was shut down for two weeks as the Weinsteins and the director fought over this and other matters, with co-star Matt Damon admitting, “I’ve never been in a situation like that.” For the first time in his career, Gilliam had met his match: “I’m used to riding roughshod over studio executives, but the Weinsteins rode roughshod over me.” They fought again over the edit, and in the end, no-one was happy: “It’s not the film they wanted and it’s not quite the film I wanted.”

If you’re ever feeling grumpy in the Yuletide, having caught one too many re-runs of Fred Claus, Gilliam’s hilarious short animation should bring snowy joy back into your cold heart. It’s a nice reminder of his roots, and of just how inventive the man can be with nothing more than a pair of scissors and a set of greeting cards.

Unbelievably, the energetic and anarchic director is now in his eighth decade, but shows no signs of letting up. In fact, attending the premiere of The Wolf Of Wall Street, he lamented that young stars today should be more badly behaved: “That’s what they are supposed to do. Go off the rails, get into drugs, die young – that’s what you are supposed to do... There aren’t as many deaths as there used to be. Rock ‘n’ roll used to be a lot more fun, everything is a bit too timid now.” In his own youth, Gilliam led by example: “I had long hair... a foolish, foolish thing. And I drove around this little English Hillman Minx – top down – and every night I’d be hauled over by the cops. Up against the wall, and all this stuff.”

For his latest film, Gilliam goes back to his roots, with many critics hailing it as the third instalment in his unofficial dystopian trilogy, after Brazil and Twelve Monkeys. It certainly has a strong similarity to those two – Brazil in particular – with a familiar hostility towards authority. Instead of Brazil’s Ministry Of Information, though, we have private corporation Mancom (though they share an oddly similar logo...). As Gilliam told the Huffington Post, this is entirely deliberate: “Corporations are the real power these days.” Paranoid and disorientating without being alienating, this is a Gilliam-soaked universe through and through.