He doesn't do interviews, or photographs, or premieres. Stars are queuing up to work with him, but there's a fair chance he'll cut their performance out and just focus on some newcomer instead. And his films are slow and spiritual and almost entirely devoid of wisecracks, explosions (The Thin Red Line notwithstanding) and comedy sidekicks. Yet Terrence Malick remains one of the most interesting directors in Hollywood, adored by actors and critics and quite a lot of the general public. With his new film, The Tree Of Life, out this week, we thought we'd take a look back at his films to date.

Terrence Malick’s first feature film, Badlands, was loosely based on the 1957 Charles Starkweather case. In that notorious spree, 19 year-old Starkweather killed 11 people over an eight day period, taking his girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate, who was 15 at the time, along with him. Starkweather was executed for his crime; Fugate served 18 years before receiving parole. Malick wrote this script himself, taking the loose facts of the case – 25 year-old greaser Kit (Martin Sheen) and his significantly younger girlfriend Holly (Sissy Spacek) travel through the US killing anyone who gets in their way – but turning it into something unexpected and strangely dreamy.

While he was writing the film, Malick also put together a slide show of images to give investors an idea of the tone he was going for, as well as videotapes of actors. But his influences were not generally cinematic – he was, he told Sight And Sound in 1975, concerned with stories about innocents out of their depths, and referenced Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer, The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew among his inspirations. Hence Spacek’s odd voiceover, where she seems more interested in tastes and sights than in the murders that happen along the way.

Malick said at the time that he tried to keep the 1950s trappings to a minimum, and maintain a timeless, almost fairytale atmosphere to Kit and Holly’s adventures – although inevitably he did meticulous research to ensure that the details were right for the time period. Shot for $300,000 in Colorado, Warners bought the rights to the finished film for $1m, a show of faith soon rewarded when the film garnered rave reviews. Already, what would become hallmarks of Malick’s style are visible: sweeping shots of the natural world, voiceover narration, a philosophical bent to an ostensible action story. Years later, Sissy Spacey said of the film, “"After working with Terry Malick, I was like, 'The artist rules. Nothing else matters.' My career would have been very different if I hadn't had that experience."

Malick himself has avoided photos for most of his career, but he can be seen here with Martin Sheen, with whom he became friends some time after finishing Badlands. Said Sheen to Empire recently, “I really got to know Terry after filming, and after Apocalypse. We ran into each other in Paris in 1981. We met on the street and I spent all my free time with him, and he became a real inspiration. There was nobody really in the business I was fond of, but his theology and his spirituality spoke to me. It was an opportunity to explore the possibility of a spiritual life, and he grounded me in that. He gave me The Brothers Karamazov and that turned me in a new direction. It made it clear that spirituality wasn’t separate from this work.”

Making Badlands’ meandering plot seem like the product of a particularly fizzy Tony Scott pitch meeting, Malick’s lovely, elliptical Western is a visual feast that ebbs and flows like stems of corn in the breeze. Sure, there’s a manhunt with actual guns and horses for fans of that kind of thing, but that’s about as propulsive as the narrative gets. The camera’s interest is on the interactions of three characters locked together in a destructive love triangle, as well as their fragile connection with the surrounding landscape. The story’s stooge is a rarely-better Sam Shepard, a dignified frontiersman duped into a bogus marriage by Brooke Adams’ migrant labourer, as Richard Gere’s tanned n’er-do-well, a schemer to the core, pulls strings that he can never entirely control.

There’s a fourth character even more impassive than Shepard’s ailing farmer. The Gothic mansion that looms above the spacious wheat fields is a reminder of the Edward Hopper’s influence on Malick’s Americana. Hopper’s 1925 painting, House By The Railroad, also a touchpoint for Hitchcock’s Bates Motel, inspired the building’s design. It’s here that the tragedy slowly unfolds. The endless railway line deposits poor workers from Chicago into the Texan Panhandle of 1916 in search of paid labour, and in Abby (Adams) and Bill’s (Gere) case, a farmer’s fortune. Arguably the greatest performance of all, though, belongs to 15 year-old Linda Manz as Abby’s whipsmart, part-soulful, part-feral sister, the observer over the unfolding sorrow and provider of the film’s mostly ad-libbed voiceover.

Days Of Heaven’s photography is the Oscar-winning handiwork of virtuoso cinematographer Néstor Almendros. Despite his failing eyesight, he was hand-picked by the director who’d admired his work with Francois Traffaut. Like his director, Almendros favoured natural light over big shiny studio bulbs. "My job was to simplify the photography,” said the Spaniard, “to purify it of all the artificial effects of the recent past." The pair transformed the Midwest (actually Canada) into a panoramic wonderland of gently swaying wheat ears, sunsets to bathe in, blazing infernos and a Biblical locust plague that’s a thing of near-beauty. This was mimicked by chucking peanut shells out of circling helicopters.

Plain sailing, then? Not really. The crew grumbled over the lack of lighting and Malick’s insistence on shooting solely in the fleeting ‘magic hour’ pre-dusk ensured that the shoot dragged on and on. Almendros, due on another Trauffaut project, had to be replaced by One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest DoP Haskell Wexler who was behind the camera for 19 filming days to Almendros’ 35. It was Almedros, though, who walked off with the Oscar, much to the Hollywood veteran’s frustration. Almendros also got to be bestest pals with Malick, who, weary from the experience and chary of being thrust into the Hollywood limelight, visited his cinematographer in Paris and wouldn’t resurface in Hollywood for another 20 years.

When Malick started work on The Thin Red Line, he'd been away from Hollywood for well over a decade. By the time it came out, it had been 20 years since his last film. Producer Robert Geisler explained the tortuous development of this adaptation of James Jones’ novel. “It didn’t happen quickly. I first spoke to him back in 1989, there were years of talking and discussions about actors, until at last he couldn’t refrain any longer. It’s in his blood. It was inevitable, I guess, that he would come back. He said we had to be careful and take our time but I thought he meant two or three years. I didn’t know that he meant ten. But it was just a question of bringing him to saturation point.” What eventually emerged was a Best Picture Oscar nominee and Malick's most high-profile film yet. Of course, that's relative: it still ended up largely overshadowed by Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan in the same year.

Based on Jones' novel (he also wrote From Here To Eternity), Malick's story focuses, loosely, on the men of Charlie Company as they attempt to take a Japanese-occupied hill on the Pacific island of Guadalcanal. So far, so linear, but what the director does is to turn what might have been a Boy's Own story into a more philosophical affair, driven more by voiceovers and the pauses between battle as the conflict itself. Significant characters include Sean Penn’s bitter Sergeant Welsh, Elias Koteas’ noble Captain Staros, Jim Caviezel’s near-angelic Private Witt and Ben Chaplin’s lovelorn Private Bell. However the real star of the film is the environment of the island, as Malick’s camera keeps returning again and again for more lingering shots of birds and plant life. Rambo, it’s fair to say, this ain’t.

Says producer Geisler, “It was very romantic, to be directed by Malick in a war story by James Jones down in the South Seas. It’s a dream. Actors were lining up around the block to meet with Terry. He’s like Halley’s Comet. You just don’t know when he’s going to do this again.” We'd argue that: Halley's Comet definitely turns up every 75 years or so. Malick's nowhere near so regular. Still, he ended up with what has a claim to be the starriest cast ever, including Travolta, Clooney, Nolte, Harrelson, Cusack and Penn – even though they all saw their roles chopped to bits in favour of lesser-known (at the time) names like Caviezel, Chaplin and Koteas. Adrien Brody, talking to The Independent shortly after the film came out, was upset to have seen his role slashed. "I gave everything to it, and then to not receive everything ... in terms of witnessing my own work. It was extremely unpleasant because I'd already begun the press for a film that I wasn't really in. Terry obviously changed the entire concept of the film. I had never experienced anything like that." But it could have been worse. Seriously, blink and you *will *miss George Clooney.

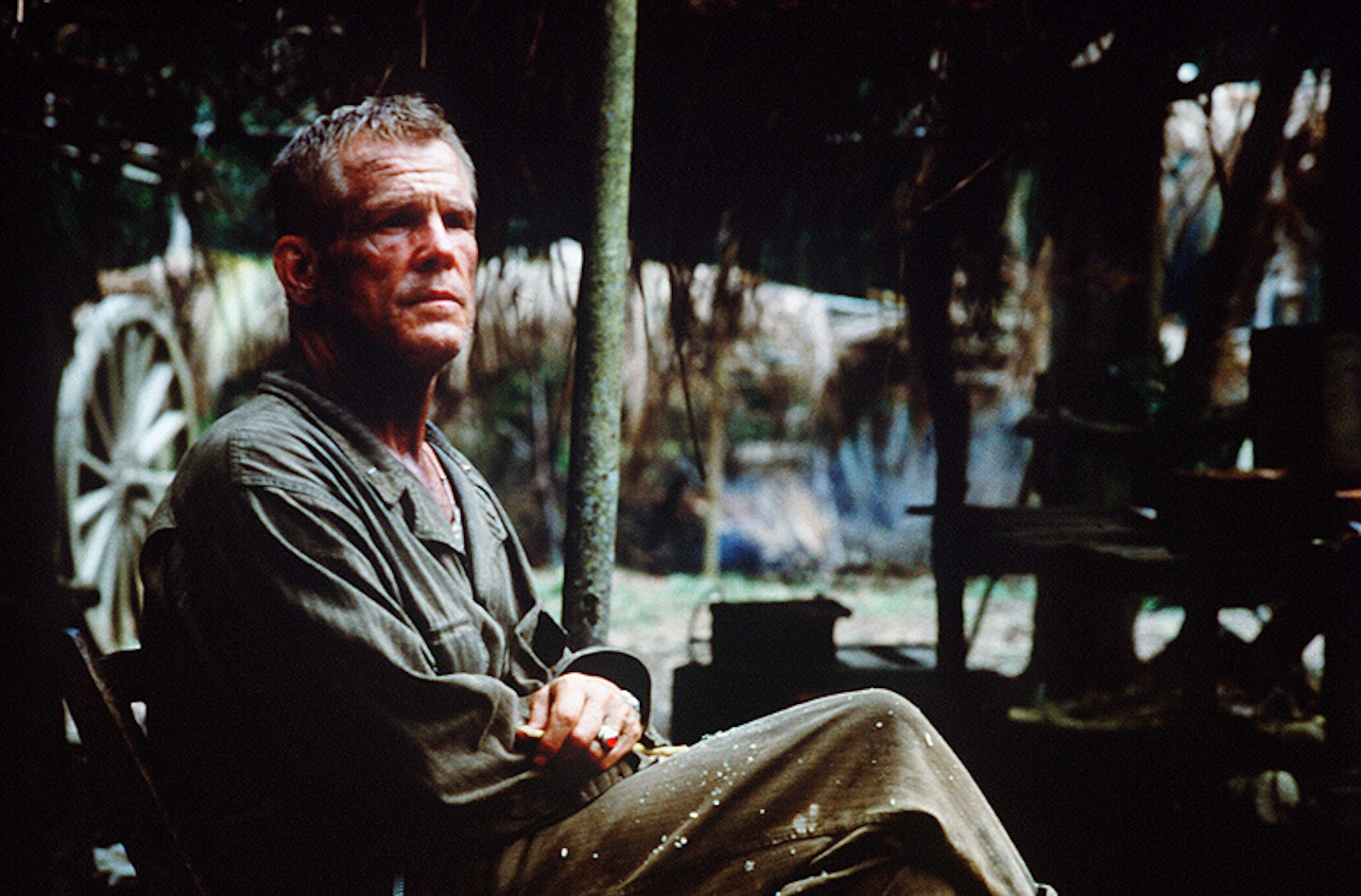

In 2003, Nick Nolte talked to Time Out about working with Malick. “'Terrence Malick is oblique. He would start shooting the scene, but watch the sky. And about six, when the sky was just right, he'd say "That's enough of this scene, let's revisit the scene we shot the other day. Nothing will match, but that's fine." He was finishing the scenes in golden light. He couldn't tell the studio he was only going to shoot in golden light, they would have freaked, so he would hold these scenes off. All those elements were thrown out, and the only new element was this light that's what it was about.” We know what you're thinking and yes, Malick does have something in common with Michael Bay: that affection for the magic hour.

Malick had long been pre-occupied with the loss of innocence and man’s interaction with the natural world, so it seems, in retrospect, an obvious choice for him to look at the arrival of Europeans in the “New World”. The script was one he’d been musing over since the 1970s, but it was only in 2005 that his epic was finally released after another planned Che Guevara film fell apart. Telling the history of the founding of Jamestown and the role played in that settlement by Powhatan tribeswoman Pocahontas (as she was popularly known, although she’s never named as such in the film), the film mixes the legend with significant nods to historical accuracy, getting Pocahontas’ age closer to her actual age, and going to some lengths to reconstruct the language of a now-vanished tribe.

Following his critical success but commercial lack-of-same with The Thin Red Line, Malick worked with a slightly smaller cast and budget this time around, but still shot expansively in search of moments rather than specific scenes. Colin Farrell played John Smith, the first white man to make contact with Pocahontas (as we’re calling her in the absence of an onscreen name), with Christian Bale as John Rolfe, who eventually married her. Along with Christopher Plummer’s colonial boss, they supported Q’Orianka Kilcher, the young unknown who took the lead. As on all Malick’s films, he changed dialogue and script as needed and sometimes went as the mood took him. Recounted Christian Bale “I would also just stay on the set the whole time. Terry liked that. Sometimes he would just be sitting there, and you didn't have the regular actor chairs. Everything would be over the period and so you might just be hanging out on a period chair and suddenly realize that they'd been filming you for the last ten minutes and you didn't even realize it. It was very nice working in that way.”

While the Disney cartoon about the same subject in the 1990s featured quite a lot of singing and overlooked the whole unhappy ending thing, Malick’s film went for a more historical approach – and if that meant fewer cheery chipmunks and wise old trees, so be it. So the film shot near the area where Jamestown was originally built, using archaeological evidence to reconstruct both settler’s cabins and Native American huts. Language experts taught the Native American cast the vanished Powhatan tongue, a form of “Virginian Algonquin” that would have been spoken by Pocahontas’ people. One central fact that’s not supported by history remains, however, and that’s the idea of a love affair between Pocahontas and John Smith. But then taking that out would be the work of a true spoilsport.

The film presented a heck of a job for 14 year-old lead Q’Orianka Kilcher. Asked about her biggest challenge, she said, “I would say learning a perfect British accent. And then I learned the entire script in a perfect British accent. Then, strip that away for the first 60 pages and learn Algonquin, and I actually made myself learn Algonquin because that’s her native language so I really would know what I was saying. And then strip half of the Algonquin away and then do different stages of Algonquin mixed with English. So that was definitely very challenging. Then in some of Pocahontas’ lowest points in her life where she goes a little crazy. Unfortunately you’re not allowed to see too much of those times because, the length of the film that’s 2 hours and 15 minutes, I think. But that was very emotionally challenging.”

“He never loved the movies”, wildchild producer Don Simpson once said of Malick, “He was more the philosopher”. Sure enough, there are more ideas packed into Tree Of Life than several thousand pedal-to-the-metal blockbusters. It’s a typically dreamlike opus by the great man. Look closely and you’ll find all the big questions asked. Is there a God? Can we hope to achieve grace in our lives? What binds a family together? And what do dinosaur fish really look like? It’s Malick’s most autobiographical movie to date (apart, we suppose, from the dino-fishies), an ode to his childhood in the shady suburbs of Texas.

The movie was shot on location in Waco, 100 miles south of Malick's hometown Austin, and in Smithville, which is located between the two. The latter was the location of the titular oak tree. It’s a spiritual totem that’s symbolises the interconnectivity of life for everyone from the Vikings to the Mayans - a recurring Malickian motif that he’s previously juxtaposed with the depravations of combat (The Thin Red Line) and colonialism (The New World). In this Palme d’Or winner, it’s grief and memory that link to the essence of existence itself, a journey that’s filtered through the prism of Sean Penn’s melancholic architect. Which, when you think about it, is basically the same plot as Transformers 3.

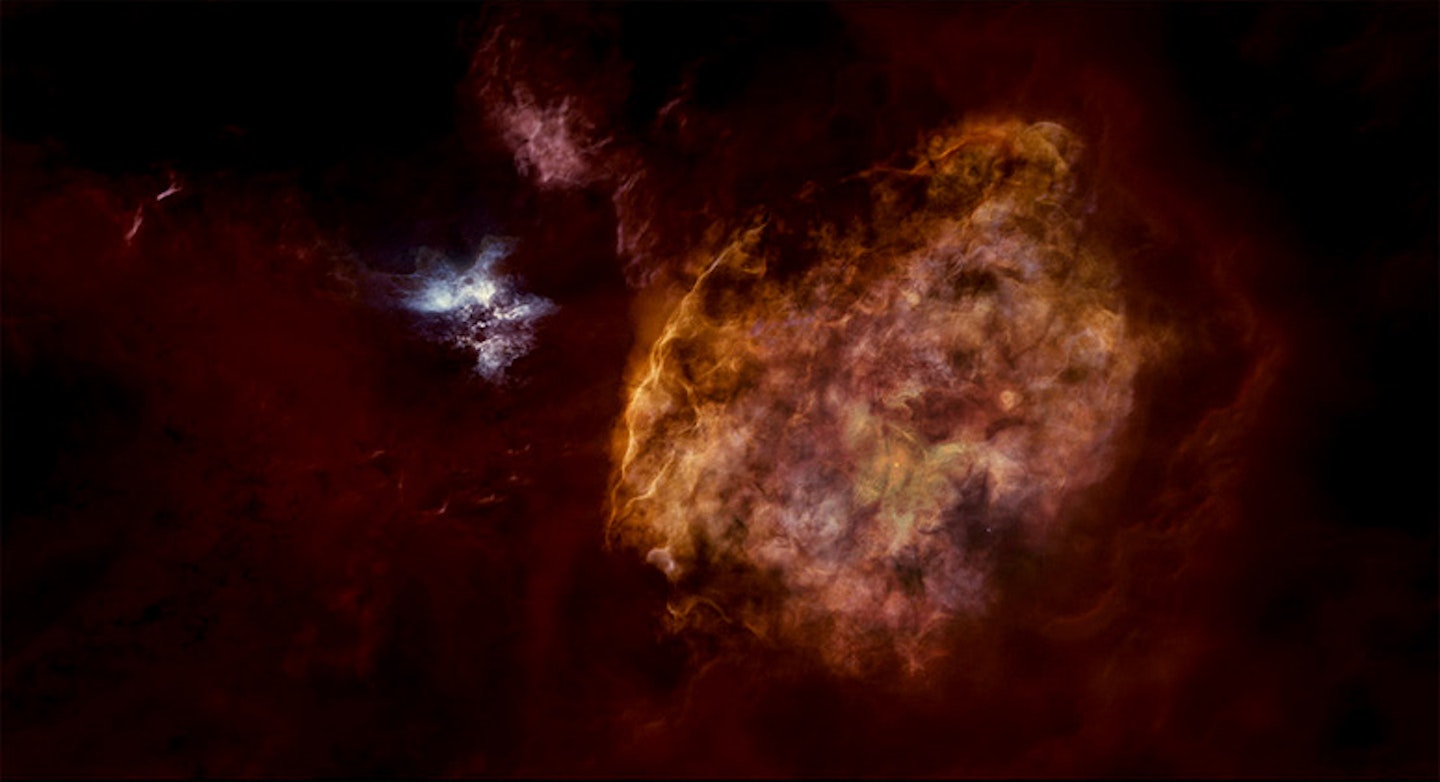

Malick is hardly synonymous with his show-stopping effects, but what with dinosaurs being thin on the ground in Hollywood and the Big Bang to recreate in all its symphonic splendour, he turned to effects genius Douglas Trumbull. The pair steered clear of CGI as much as possible, preferring what Malick called “the old methods of 2001” - a reference to Trumbull’s work on Kubrick’s sci-fi classic. “We worked with chemicals, paint, fluorescent dyes, smoke, liquids, CO2, flares, spin dishes, fluid dynamics, lighting and high speed photography to see how effective they might be,” says Trumbull. “It was a free-wheeling opportunity to explore, something that I have found extraordinarily hard to get in the movie business.”

The three-act structure may go the way of the dinosaurs in The Tree Of Life, but the kaleidoscopic visuals are as dazzling anything we’ve seen this side of Avatar. Malick, who unlike many auteurs has worked with different cinematographers from movie to movie, is building a rich creative partnership with Mexican DP Emmanuel Lubezki. “Photography is not used to illustrate dialogue or a performance,” Lubezki told the LA Times, “We’re using it to capture emotion so that the movie is very experiential. It’s meant to trigger tons of memories, like a scent a perfume.” Malick and Lubezki are working on the director’s so-far untitled next project, so prepare your eyeballs for more rapture.