When Dennis Muren, Gene Warren Jr, Stan Winston and Robert Skotak bounded onto the stage to receive the Best Visual Effects Oscar for Terminator 2, it came as no surprise that Muren, the Visual Effects Supervisor at ILM, was grinning just a little bit wider than the other three. Using a combined three-and-a-half minutes of footage, his team had dropped a tactical nuke on the business of special effects, rewriting the rulebook with the film’s malleable antagonist. Forget Helen of Troy, the T-1000’s was the face that launched a thousand ships, a million aliens and a park full of dinosaurs – and that was only the beginning.

Muren’s shape-shifting wizardry triggered a surge in imitators, everything from Star Trek to Michael Jackson hitching their cart to ILM’s morphing bandwagon. But if T2’s Swiss-army-foe had become the posterbot for CGI, it owed its very existence to a dripping tentacle in 1989’s The Abyss. The ‘pseudopod’ sequence in Cameron’s previous film had taken nine months, lasted 75 seconds and proved that technology was almost catching up with the filmmaker’s fevered imagination. It was, as Fox’s Tom Sherak once bemoaned, as if the entire waterlogged debacle had been just a test reel just for Terminator 2.

Not content with pinning the success of an entire production on experimental, largely unproven technology, though, Cameron also had to wrestle the rights away from a difficult production company (Hemdale) and an ex-wife (Gale Anne Hurd), convincing Carolco to dole out $5 million apiece. With a budget of around $100 million, Terminator 2 seems almost modest next to today’s cash-snorting productions. Indeed, Cameron himself would rack up more than that with True Lies, double it with Titanic and spunk half that on carob bars while making Avatar. But back in 1991, with a price tag 15 times that of The Terminator, T2 was the most expensive movie ever made.

For all its kinetic pace, Terminator 2 is a film which pulls at the heart just as it squeezes it.

If the CGI traced its ancestry to Cameron’s Abyss then the story he and co-writer William Wisher came up with was all Aliens. Like his sequel to Ridley Scott’s film, T2 is an evolution as well as a continuation; in this case a chase movie writ large, with higher stakes, a graver threat and the simplest of desires (stay alive) replaced by one far grander (save the world). At its heart was a single stroke of genius: the Terminator, the cyborg that didn’t know pity or remorse, that absolutely would not stop until you were dead, would become the hero.

Arnold-as-saviour was the movie’s secret weapon: an efficient, unstoppable killing machine… with a heart. But while the Tin Man is discovering how to love, Dorothy is busy field-stripping an M16. Like Ripley’s transition from victim to vindicator, Linda Hamilton’s Sarah Connor storms into T2 a Camel-chugging, steely-eyed soldier with sculpted musculature almost as impressive as Schwarzenegger’s. As the machine is playing mummy, it’s she, drained of compassion in black fatigues and dark glasses, who inhabits the role of mechanical killer.

Thirteen year-old Edward Furlong (pulled straight out of a Pasadena youth club) gives a raw, unhoned performance as the young John Connor, lending humanity’s saviour a realism (complete with punchable, obnoxious streak) Cameron had failed to find among the ranks of child actors he’d tested. The true discovery, though, was in thirty-two year-old Robert Patrick, then living in his car and with only a goon in _Die Harder_to distinguish his CV. Millions of dollars and countless hours (one 15 second effects shot took ten days to process on an early nineties render farm) would have been for nothing without a suitably menacing T-1000. Cameron’s “Porsche” to the T-800’s “Panzer tank”, Patrick cuts a lean, athletic figure; all coiled power and deadly agility. Nowhere is the difference between the two models more pronounced than when Patrick sprints after the heroes’ escaping car, bounding towards the fleeing vehicle like some kind of amped-up, homicidal cheetah. All prowling, shark-like aspect — with dead eyes to match — Patrick’s performance is every bit as chilling as Schwarzenegger’s original, making up in atavistic menace what he gives away in bodyweight. When the two first clash and its Schwarzenegger crashing head-first through a plate-glass window, we have no trouble believing it’s the big guy who’s seriously overmatched.

Viewed now from a world in which CG-heavy action sequels dominate the box office, Terminator 2 still manages to stand head and metal shoulders above them all. Cameron’s forceful direction and flab-free writing give this two-and-a-half-hour runtime the feel of a movie half that length. The pell mell chase through the canalways (complete with twirling Winchester 1887) would make a satisfying climax to any other movie, here’s it’s just the appetiser. A masterfully tense prison break and subsequent flight flashes past in moments and, one bleeding Joe Morton later, we’re into the Cyberdyne assault. A gleeful Schwarzenegger rains holy hell down on most of the LAPD with the minigun from Predator before breaking out a grenade launcher and ultimately leaving the entire building in flaming fragments. It’s a pyrogasm of budget well-spent and even this is merely setup for the grand finale. Those final thirty minutes, with their freeway chase, tanker crash and steel mill showdown are as fast and furious as any third act before or since – the fruits of a single, heroic sprint of screenwriting from Cameron.

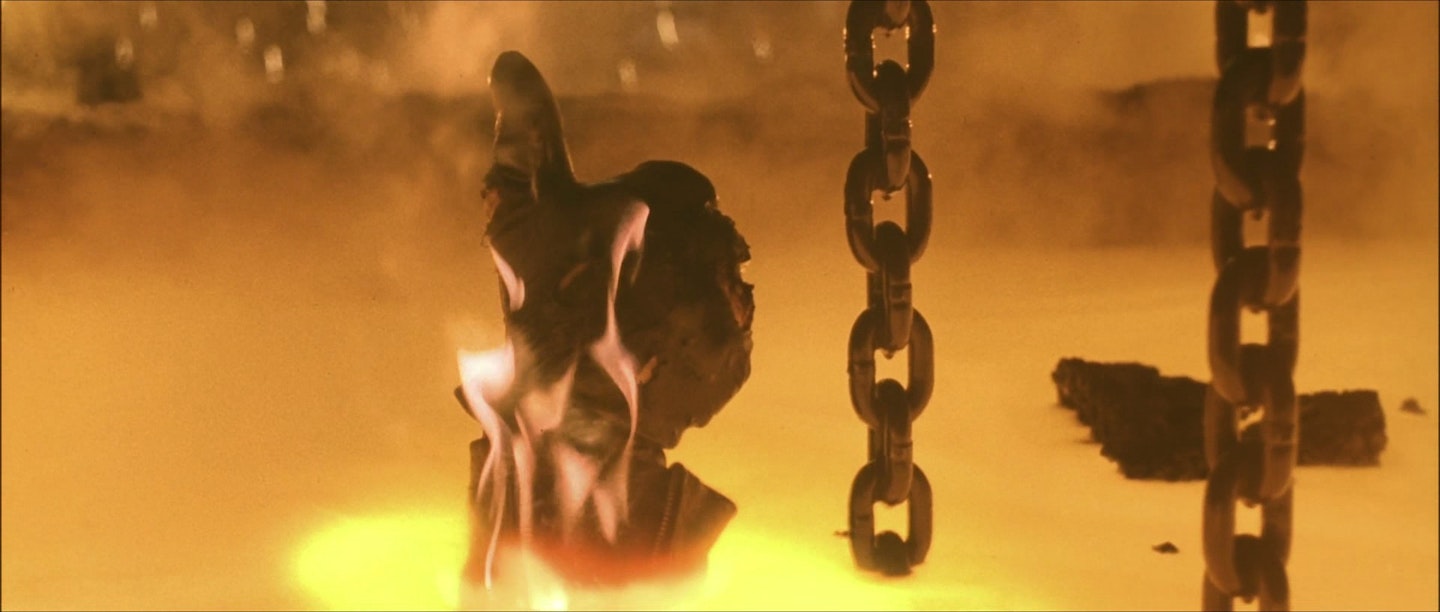

But for all its kinetic pace and full-auto thrills, Terminator 2 is a film which pulls at the heart just as it squeezes it. Like its star, this is a machine wrapped in human skin and in its final moments delivers on the promise Cameron made to Schwarzenegger as production began: “The ending is going to be like Shane,” he had said. “We’re going to get the audience to cry for you – the biggest, coldest, motherfucker, machine bad-guy in history.” As a solemn Sarah Connor lowers the Terminator into molten steel and Brad Fiedel’s haunting synth cries the eulogy, we’re left as tear-streaked as the boy he leaves behind, just about holding it together until that final upraised thumb.