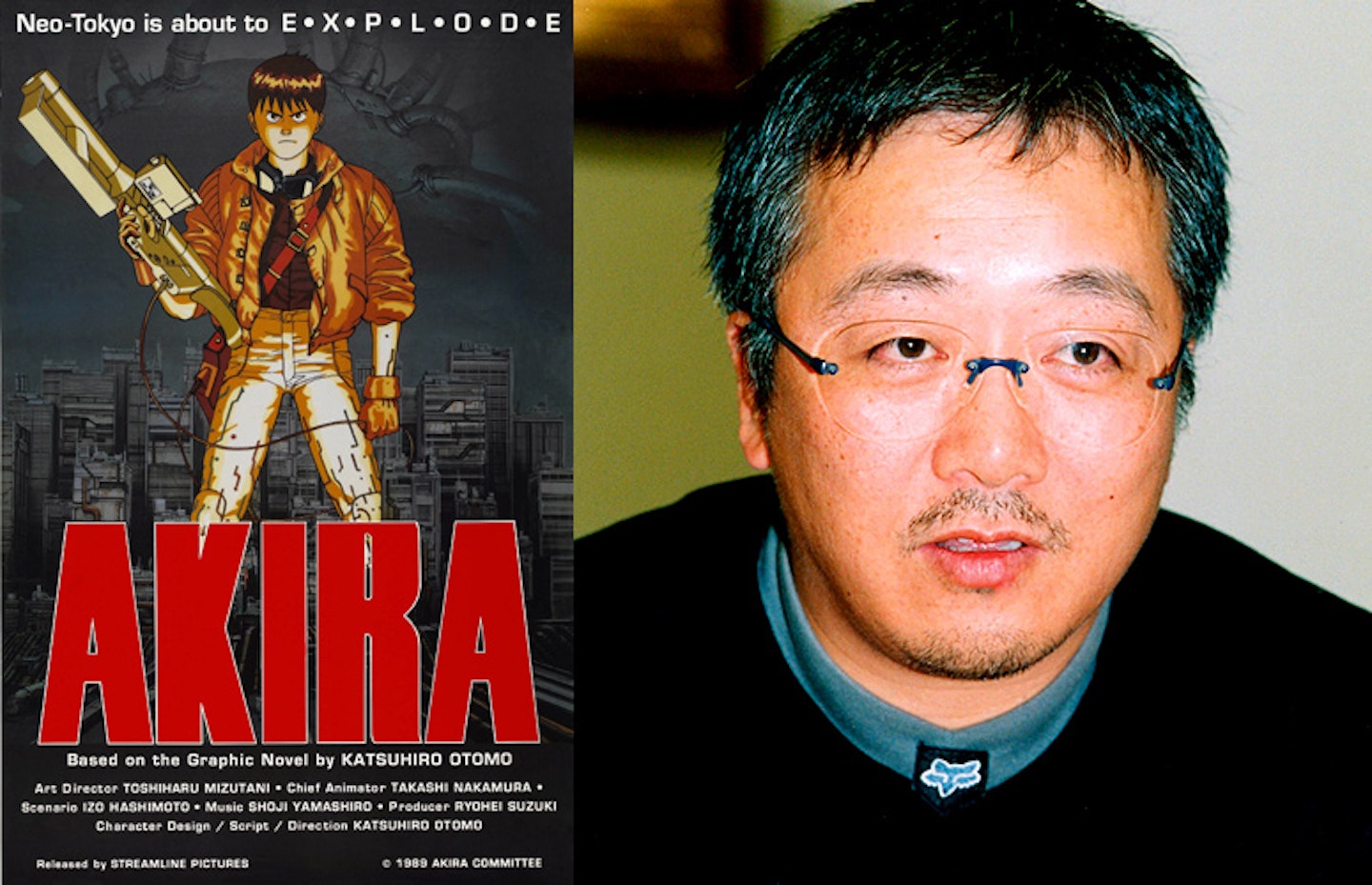

In 1988, Katsuhiro Ôtomo turned his bestselling manga into a $10 million feature-length cartoon. The result, Akira, is quite simply one of the greatest animated movies ever made. With its release in Neo-Tokyo-enhancing Blu-ray, Empire talks to Ôtomo and traces the making of the cartoon classic that helped shape the modern blockbuster...

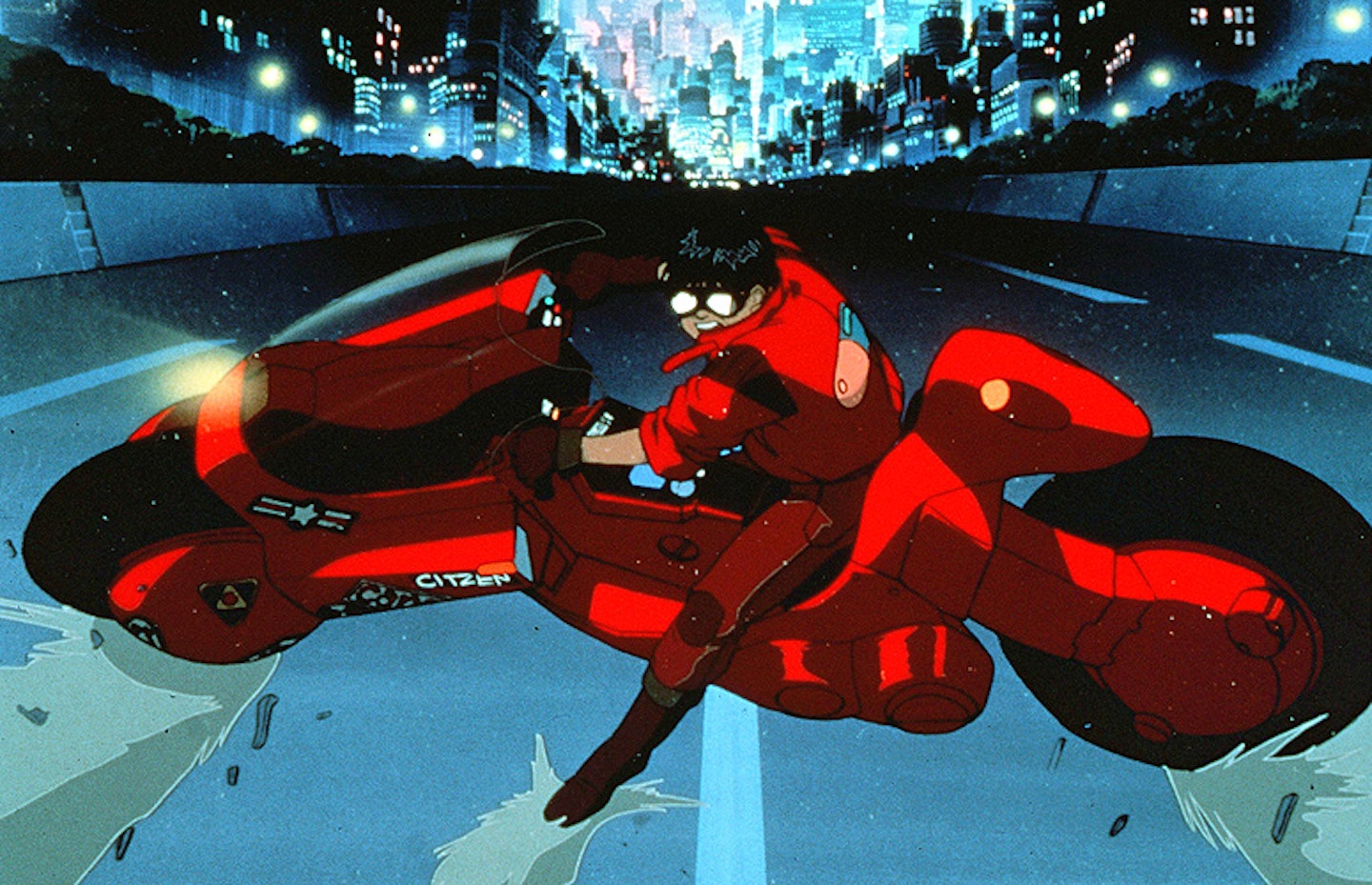

The audiences who saw the first Godzilla (1954) might have been watching a documentary; after all, the damage by the scaly Big G was no worse than that meted out by B-29s. Three decades on, the apocalypse was still a threat, but also a thrill: a way for a new generation to trample down the old world and build another. In Akira, one of the main characters, a colonel, mourns that, “Gone are the passion and joys of reconstruction.” But destruction is also joyous and passionate. When Akira’s director, Katsuhiro Ôtomo, was asked which book had the greatest impact on him, he nominated H. G. Wells’ War Of The Worlds, in which Martians obliterate 19th century London and the Home Counties. (Ôtomo would beat up Victorian London in a later anime epic, Steamboy.) Akira is full of smashing down and building up — sometimes at the same time — as creation and destruction become part of one great, organic process. Our first sight of Akira’s Neo-Tokyo is a visceral red shape suggesting a heart, lungs or guts. Teen biker gangs rule the streets on huge, phallic motorbikes that blur into neon-coloured speedlines. Armed police battle the rioting unemployed, terrorist gangs adding to the mayhem. And in a super-deluxe nursery, housing a top-secret state project, three withered children await the return of their divine brother. A boy named Akira...

The bikers (the main characters) bomb cars, smash windows and beat each other into pulpy messes, but they’re part of one organism. We see them from a God’s-eye viewpoint passing under mammoth skyscrapers, reduced to white dots, like blood cells, or zooming in aerial battles through Neo-Tokyo’s flooded bowels. At the climax, a boy swells into a fantastic bloated giant that mewls, pukes and excretes its way into oblivion. The film’s high-energy transformations are driven by cosmic forces, hokily explained but brilliantly visualised.

So It's Begun...

The director Ôtomo started his career as an artist-creator of manga comics, the format in which Akira was born, but he’d always been a film geek. A country boy, Ôtomo travelled three hours by train to see the latest films when he was still at high school. He was the right age to see Easy Rider and Bonnie And Clyde, along with assorted yakuza pictures and Japan’s “pink” (soft porn) films. His first strips, published in the 1970s after he moved to Tokyo, were mostly short stories, but they grew in scale. His 1980 serial, Domu, about a paranormal battle between a girl and an old man in an apartment block, was hailed as a masterpiece; it was the first manga to win Japan’s sci-fi “grand prix” award. Then, in December 1982, Ôtomo released the first part of Akira. It was serialised in Young magazine, a 300-page anthology manga magazine for high-school and college students.

Akira was a hit — the first collected volume was a number one bestseller. Yet Ôtomo later claimed Akira’s world could only have been fully realised in animation. “It is extremely difficult to express the depth of such a vast city,” he said. “In the comic, I used each issue to build more depth and size. But in a film, you get to combine this all into one. It’s much more convincing… I could really create the type of environment that I wanted to depict.” When the film entered production in the mid-1980s, Japan was in its booming “bubble” economy years, and companies were ready to invest in anime. When Akira’s art director asked Ôtomo (who would storyboard the film) what the film’s “world view” would be, Ôtomo drew him a dirty, grungy city sidewalk, the lived-in detail rivalling any live-action set. The art director looked at it and declared it impossible. But then, Akira had a budget of 1.1 billion yen (about $10 million) and resources to match: a 70-strong staff working round the clock, new technology that allowed for character lip-synch, and the resources to make “full” animation on 12 or 24 frames a second. (Even Studio Ghibli films use semi-limited character animation, which is why they’re less smooth than their Hollywood rivals.)

“Producing animation is very similar to making a live-action film,” Ôtomo says. “I used the techniques and forms best suited to my purposes: cinematic styles, building up speed, cutting and editing.” At the same time, many of Akira’s character names and story points hark back to a vintage comic and cartoon series, Tetsujin 28 (Gigantor in America), in which a young boy operates a remote-controlled robot. “Heck, considering Akira’s basic concept is that a secret weapon from a past war is resurrected, you could say that Akira was based on Tetsujin 28,” Ôtomo says.

But Ôtomo was also inspired by what he saw in 1970s Tokyo. “There were so many interesting people… Student demonstrations, bikers, political movements, gangsters, homeless youth... All part of the Tokyo scene that surrounded me. In Akira, I projected these elements into the future, as science-fiction.” Ôtomo further drew on the 1960s zeitgeist. Akira’s climax takes place in an Olympic sports stadium, a potent Japanese symbol of reconstruction. The 1964 Olympics were a milestone for the post-War country, as this summer’s Beijing event has been for 21st century China.

Jonathan Clements, co-author of the Anime Encyclopedia, sees deeper, more provocative, historical echoes in Akira’s flurry of subplots. Halfway through, the colonel character brings about a military coup, echoing an actual (failed) insurrection in 1936. The adults in Akira carry out cruel medical experiments on children, recalling Japanese war crimes. The clash between Japan’s old and young generations is also a hot issue in a fast-changing country. After Akira, it would play out in one of the biggest 1990s anime, Neon Genesis Evangelion, ostensibly a robot show like Tetsujin 28, but with a boy hero who’s driven by his rage and bitterness towards his commander, who’s also his dad. Akira’s lurid hyperviolence would resurface in Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale, the ultimate Japanese youth-alienation fantasy, where evil adults try killing their kids off completely.

Akira also anticipates the recent evolution of Hollywood comic-book movies. It has the manic violence of The Dark Knight (there’s even a biker gang dressed up as clowns), but the film is closer to Marvel franchises like X-Men and Spider-Man. Akira’s monstrous character Tetsuo is a youngster who finds horrific forces mutating his body. Peter Parker shoots out embarrassing strands of web-goo, but Tetsuo’s whole body engorges into a swelling, seething, liquefying ball of flesh. Akira further foreshadows some of the TV show Heroes, such as the season one set-piece where a radioactive man goes uncontrollably nuclear.

None of which is surprising, given Ôtomo’s love of American pop culture. He said of the first Akira collection that, “I wanted the page-count, the contents, the paintings, everything about it to create a deep, full, American comic-style world.” Archie Goodwin, Marvel editor-in-chief during the 1970s, noted that, “Akira seemed to fit the tastes of American audiences... Ôtomo was dealing with a science-fiction story, which they like, but he was also dealing with beings with paranormal powers, which is a popular theme in American comics and science-fiction now.”

Akira also anticipates certain Hollywood comic-book films in its overstuffed plot. The film compresses hundreds of manga pages, originally published over several years, into two dazzling but very confused hours of animation. Subplots and support characters are truncated or plain forgotten: plot points are vague, even contradictory. Perhaps it was just the difficulty of compressing such a long strip, which hadn’t even been finished when the film was made. It also seems possible, though, that Ôtomo wanted to throw in extra twists to surprise fans of the manga. For example, the “Akira” that Tetsuo unearths in the film is very different from the one he finds in the strip.

And yet, this messy plot is a big part of Akira’s fascination. More than any sci-fi film since Blade Runner, it hurls the viewer into the middle of a world that bleeds from the screen in multiple hinted backstories. The action scenes are a blend of bloody carnage and information overload. The first 15 minutes serve up (in rough order) the end of the world, a new metropolis, rioting students, biker thugs in high-speed chases, and paranormal beings fleeing from sinister men in black, the whole heady montage overlaid with TV news reports and dog-food commercials. The spectacle takes on muscular momentum, driven by the brilliant score by the group Geinoh Yamashirogumi that’s full of explosive breathing and clacking percussion. Later in the film, an empowered Tetsuo fights his way through tanks and helicopters, taking on a supergirl on a huge, metal globe as giant pipes and energy beams destroy the surrounding infrastructure. Then a military satellite comes into play and the battle goes into outer space.

A Ghost In The Machine

Akira demands to be seen on the big screen. Harry Knowles, founder of Ain’t It Cool News, remembers, “College theatres got hold of that film and just played it over and over and over. It became a midnight thing… When I was at college, Akira and Ghost In The Shell (the next big anime film import) played forever.” Akira became a true midnight movie, befitting an action film that often feels like an endless fever dream. In Britain, too, many viewers first caught Akira at one-off cinema showings around the country. One of the first to see it was Andy Frain, former marketing manager at Island Records, who checked it out as a possible commercial proposition. “It blew me away,” he said. “I’d never seen anything like it. It was like an animated Blade Runner, clearly not for children, but a well-crafted, philosophical movie that happened to be in animation.”

America had enough of a Japanese animation fanbase for Akira to be released on video. In Britain, where anime was almost unknown, Frain set about creating a new brand. “I started thinking Akira was more than a great film; it might be a phenomenon. Were there more films like this in Japan? If so, we could treat them like a record label, like Def Jam, a genre in itself. Nobody in Britain knew the names of the films, the names of the directors, anything about them other than that they were brand new (for Britain) and that if you enjoyed one, you were likely to enjoy others.”

The result was the so-called “manga” cartoon brand that was unleashed in Britain in the 1990s. (Asked if he considered using the brand name “anime”, the Japanese word for animation, Frain replied that the phrase “anime cartoons” would be like saying “film films”; “We were giving a doff of the cap to the original comic source.”) A few years later, Frain’s new company, Manga Entertainment, would co-produce another sci-fi Japanese animation, Ghost In The Shell, which would be one of the main inspirations for The Matrix.

In the years after Akira, Manga Entertainment caught flak for its emphasis on sex and violence, which fans said misrepresented the medium. But “anime” was equally stereotyped as violent animation in America, at least until Pokémon and Spirited Away arrived a decade later. The apocalyptic vision of Akira seared its way into the global consciousness, even in parts of the world torn by war. In 1993, a Japanese critic was walking through bombed-out Sarajevo when he was amazed to see a mural from Akira on a crumbling wall. In the panel, one of Ôtomo’s scowling teen bikers glared out at a world gone to hell.

The caption: “So it’s begun!”