There are few film directors out there more iconic than Steven Spielberg – the man behind Jaws, Raiders Of The Lost Ark, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, and- well, we could go on and on. But now he’s also the filmmaker behind a brand new adaptation of West Side Story, bringing the legendary Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim musical based on Romeo & Juliet back to the big screen, this time with Rachel Zegler and Ansel Elgort as star-crossed lovers Maria and Tony, divided by gang tensions and racism in ‘50s New York.

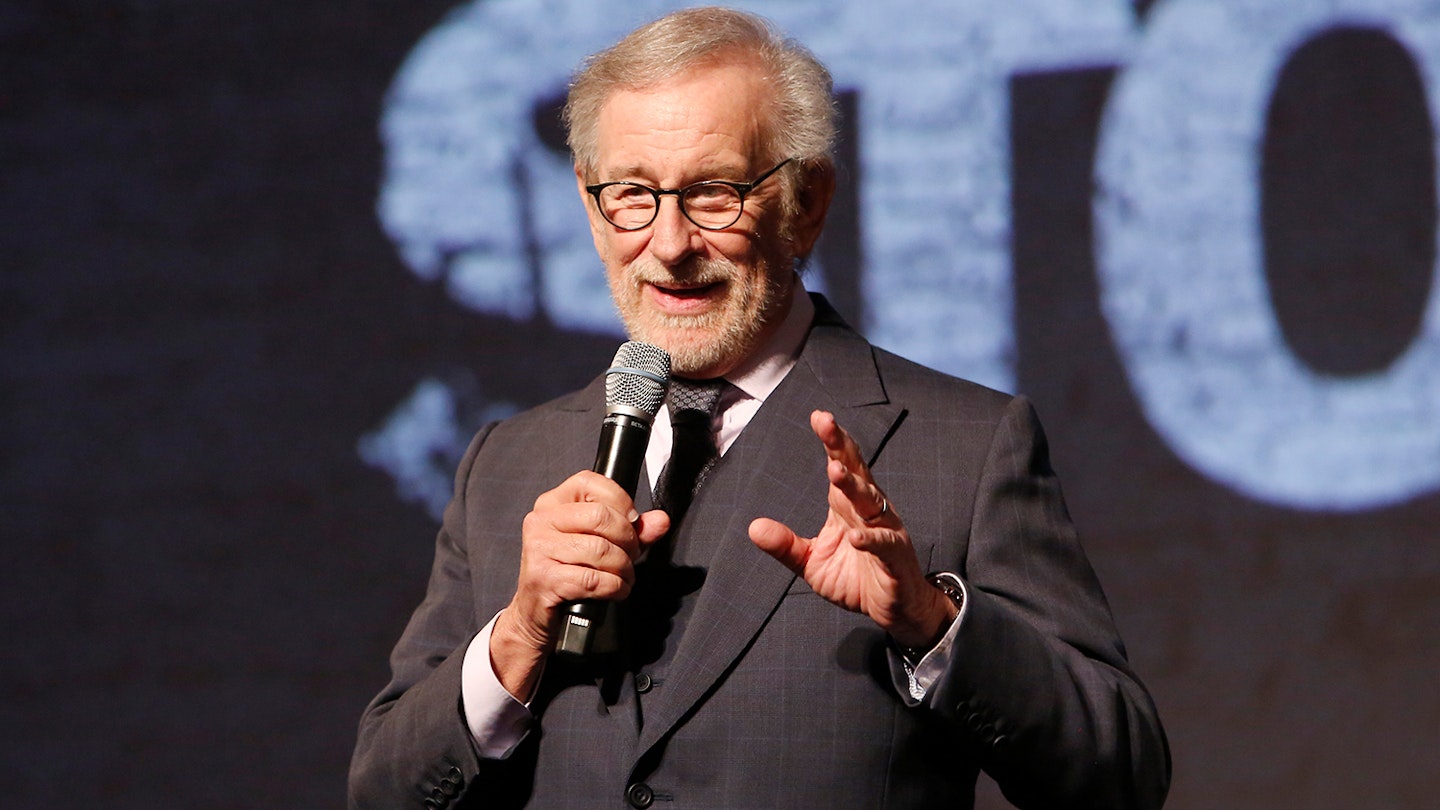

On the Empire Podcast – available to listen to now on your app of choice – we sat down with Spielberg himself, talking his long-time love of West Side Story, the gift of the late great Stephen Sondheim’s astonishing lyricism, the musical sequences that scared him the most, and the art of making movie-musical numbers that really sing. Hear the full interview on the podcast now, and read it below.

EMPIRE: There’s been a long wait in your career to finally direct a musical. Why was the wait so long for you?

STEVEN SPIELBERG: You know, I've asked that question to myself many, many times, because it was always West Side Story I wanted to do. Since I was 10 and listened to the original Broadway cast album, right up ’til I saw the ’61 movie – the brilliant, inimitable classic by Robert Wise and Jerry Robbins – and right through the stage productions I've seen over the years, it's just been my favourite musical, and the music has been in my life, all my life. And it's been in the life of my children too, because when dad likes something, he wants to share it with the kids – and I got the kids humming it and memorising some of the words and play-acting some of the roles with my video camera going on weekends. And so it was just a matter of time.

But that actual tipping point between just infatuation and then commitment to a reimagining, it didn't happen overnight. It just was the kind of thing that happened by very quietly asking questions – for instance, if I went to the estates, what would they say to me if I asked them, could I make another movie out of this? If I went to Tony Kushner and asked him, ‘Would you agree to adapt a screenplay from the original Broadway musical – not from the ’61 movie, but from the original source material? Would you do that?’ I started making little quiet enquiries. And I started to get a little bit of interest back from Tony who was interested theoretically, and actually from Stephen Sondheim who thought it would be interesting.

That's what gave me at least the temerity to ask for a meeting with all four estates. I went to New York and I met with Rick Pappas, Stephen’s lawyer and friend and representative – Stephen was not there for the meeting, he chose not to be – and I met with the other three estate owners, the trustees from the Jerry Robbins estate, Jonathan Lomma, and David Saint from the estate of Arthur Laurents, who wrote the book. And certainly Nina and Jamie and Alexander Bernstein, Lenny's actual kids. We all sat in a room for hours and met, and I simply had to sell my ideas to them and I had to give them good reasons why it was time to bring this back out to a generation, sadly, that hasn't really heard West Side Story. And that was the generation I wanted to reach with this, because I think West Side Story has clearly stood the test of time, it's been around for 64 years, and it's going to be around hopefully forever.

It’s stood the test of time, and it also speaks very much to our times now – that must been something that was on your mind.

It was, very much so, because – in a more contained, microcosmic way – what happens on stage and the original production, the destruction of the Jets, is what has been played out today with the division that we are all super aware of in this country and around the world.

I always wanted to block the actors the same way Justin Peck blocked the dancers. I never wanted to make us forget that we're in a musical.

Absolutely. So you have been, as you said, playing around with a video camera previs-ing shots for years, essentially. How many of those shots that you planned at home made it into the finished film?

Well, probably none of the shots I did with my little video camera at home got into the film, sadly. Or not really sadly – I think I got on a learning curve once I committed to telling the story and mounting the production. I realised that you can love musicals as I have all my life – I've seen every Arthur Freed-produced musical that MGM ever made, and things way before that during the Gold Diggers era of the ‘30s, post the depression – but you can't be an audience and presume you can direct a musical. And so I went through a period of learning how to do this.

One of the ways I did it was, thankfully, we had four and a half months of dance rehearsal, staging these numbers with Justin Peck, the choreographer, his wife and associate Patricia Delgado, and Craig [Salstein], who worked with both of them. While he was teaching the steps, we were talking about how the choreography was another way of telling the story. It wasn't just, we stop the movie to dance and sing and then we resume the narrative. But the narrative is the dancing, the narrative is the Stephen Sondheim lyrics and the Leonard Bernstein score, it’s the book, it's everything combined. It's all these disciplines combined to simply advance the story. And so I was able to actually take another video camera and film over and over again, in a rehearsal hall, each of these numbers until I felt confident I could pull this thing off.

Wow. What was the sequence that kept you awake at night, if indeed there was one?

Well, it's called the ‘Quintet’. Stephen Sondheim always corrected me when I called it the Quintet – he said, ’It's not a quintet, it’s a quartet, stop calling a quintet!’ But that's how it's been known for 64 years, and Steve said, ’64 years ago I objected to them calling it that! Where's the fifth voice?’

But that was what kept me up at night. That is an operatic sequence – less dance and much more action, which I'm accustomed to, but being accustomed to action, it surprised me that I was having so much difficulty mounting this musically, because it had to be mounted to the note. In other words, it's more about tempi, not film editing. It's all about the mathematics and the science of a musical. It's not just art, it's also a lot of math and science, and I'm not used to being constrained and being told, ‘You can't go past that bar of music, you can't go past that measure, you just can't do that.’ And I accepted that, and that was fine. But that basically made me work in a different framework – I had to bring a whole different skillset to directing music as opposed to directing, you know, the rangers landing on Omaha Beach.

In terms of camera movement, in terms of the actors blocking, everything?

In terms of the blocking of the actors, because I always wanted to block the actors the same way Justin Peck blocked the dancers. I never wanted that sequence to make us forget that we're in a musical. Even though they’re singing, I wanted even the blocking to feel like it was dance, even though it wasn't being expressed that way in that particular scene. So that was what kept me up at the beginning. But look, every sequence kept me up at night. There's not one musical sequence in this movie that didn't have me pacing my bedroom at three o'clock in the morning. I probably averaged – and I'm exaggerating, my wife will bear me out – about five hours of sleep a night for four and a half months filming this in New York and New Jersey. Which is okay, except when the film wrapped I was sleeping 10-, 11-hour nights to catch up.

So how was post-production, then – was it a virtual breeze compared to shoot?

Yeah it was, because I shoot most of my movies for the cutting room. Meaning I don't just arbitrarily set up a shot that I don't have a place for in the substructure or the superstructure – there's always a place for the shot. And a musical really sharpens that discipline even more. So pretty much everything fell into place, because every single shot had a place in the broad musical narrative. And so nothing really could be taken out of sequence and put somewhere else. In a regular movie, I can steal a shot and put it somewhere else and the audience doesn't know, but in a musical you can't do that.

Sondheim's lyrics were a gift to the ages of anybody who loves storytelling through music – whether it's opera or musicals, it's a gift.

You’re renowned for amazing opening shots, and this movie is no exception. Can you talk about where that comes from? Is there a moment of inspiration, does it derive from conversations you have with Tony or with Janusz Kaminski, or with other collaborators?

Well, the shot itself basically came from just my process of storyboarding. And the opening of the script describes San Juan Hill being razed by the wrecking ball in order to make way for the Lincoln Centre For The Performing Arts. In the script, Tony describes a shell of the main building already constructed. I didn't want to do that, but instead I wanted a big billboard to show what it's going to look like – an artist's rendition of the Lincoln Centre when it's all complete. And I wanted the camera to be able to crawl up the sign.

And so I did that shot first where it crawled up the sign, and as we get to the top of the sign we look at four blocks of amazingly-constructed ruins of a part of San Juan Hill that Adam Stockhausen, our production designer, had built in Paterson, New Jersey in a huge parking lot. And then beyond that, you can see right up to the Hudson River and that's all digital, but everything in the foreground and middle ground is actually built – that's real. That was what I had planned on doing, and I shot a lot of that already. I always wanted to have the camera come down to the grey ground and you see stones moving and suddenly the ground explodes open and it's basically one of those basement trap doors, disused because it's got tonnes of debris on it, and then we see Action – the first Jet that comes out of the hole.

But when I later shot the end of the movie, I found a shot that basically puts a fire escape in the foreground. I don't want to give anything away, but it does involve a fire escape and the camera slowly cranes up through an entire fire escape for the very last shot. Shooting that, it suddenly gave me the idea that we needed a bookend. So I asked Adam Stockhausen, could he get a bunch of old rusty fire escapes, and let's make a debris field of fire escapes taken off the buildings before they were demolished in San Juan Hill. So the opening shot then was augmented, and I added the shot of the camera going over all the demolished fire escapes lying on the ground until we get to the sign, and then we're able to reveal what's happening.

It was tremendous. It also brought to mind Saving Private Ryan, in a strange way. I don't know whether that was something that was that was on your mind.

That's good. It didn't occur to me. But it starts in stillness, and Saving Private Ryan also starts in stillness.

One of the interesting things about West Side Story is its cultural impact – it’s become both a cultural touchstone, but also something that has been very heavily parodied. And what I thought was really interesting is how quickly you reclaim the Jets clicking their fingers from parody.

I didn't care about the parody at all. I didn't feel that West Side Story could exist as West Side Story without the clicking of the fingers, without the snaps. I thought the snaps is as important to West Side Story as Gene Kelly is to An American In Paris, and I just would not have been able to – in all good conscience – not have the snaps because I wanted to be different or original. There's a lot of conformity to the original stage play, which is what inspired us more than anything else. When I was doing my storyboards, I only used the original Broadway cast album with Carol Lawrence singing, [rather] than any of the other subsequent treatments, including the movie score. But that was very important, the snaps.

Also, you have to understand that the characters are so different than the original stage play. The Jets really hate the Sharks. But the Sharks don't hate the Jets. The Sharks are putting up with the Jets. They're tolerating the Jets. A personal thing happens between Bernardo and Tony involving Bernardo’s sister at the dance in the gym. But during all that, and after all that, and before all that, you've got these migrants from Puerto Rico who are chasing the American dream, and they've all got jobs, they're all working people. Anita’s got a job, Bernardo’s got a job. He’s a boxer, but they all work. Chino works. He's got a trajectory to success in his life.

But the Jets are like fourth-generation white immigrants, pretty much from dysfunctional families, many of them homeless, and many of them who are sticking together because that's the only family they got. And they are actively aggressive toward the Sharks, actively. This whole thing starts because the Jets do something to their national symbol, which is very important to the Puerto Ricans. And so, you know, when we hear the song in the ‘Quartet’ – I'm not going to say ‘Quintet’ in honour of Steve – when you hear, ‘Well, they began it / Well, they began it.’ Well, it's obvious who began this. And that was a real change that we wanted to emphasise in our version of West Side Story.

You mentioned Stephen Sondheim, who recently passed away. His lyrics are so dense and so complicated – did that present a particular challenge to you?

No, not a challenge at all. The lyrics were a gift to the ages of anybody who loves storytelling through music – whether it's opera or musicals, it's a gift. Now, Steve always wanted to compose, not just write the words, and so both West Side Story and Gypsy were jobs he took. What he really wanted to do was Company and Into The Woods and Sunday In The Park With George and A Little Night Music. But he was convinced by his mentor, Oscar Hammerstein – some mentor, by the way – to take the job he was about to turn down. When Arthur Laurents introduced him to Leonard Bernstein, he needed the night to think about it and was all ready to say no until Hammerstein said, ‘Look, who you’re going to be working with – Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents, you're working with with Jerome Robbins! Are you crazy? You must say yes to this!’ So I've never felt that Stephen felt that West Side Story was his favourite work. It’s when he started becoming a nonlinear experimental composer, artist, where he really started to change the culture of theatre.

The Columbo episode ‘Murder By The Book’ played such a big part in your early career. I'm a huge Colombo fan, and just wanted to ask about your experience on that – your experience of working with Peter Falk and almost crafting that character.

He was great. He got a big kick out of me because I was so young. I directed the first show of the series – I didn't do the pilot, that was done a year before – but I did the first show of the series for NBC, and I just remember he got a big kick out of me, because I was really young and I looked younger than my actual age. He really took me under his wing and he was great to work with, and because he was trained by John Cassavetes and he was expecting surprises, I was a surprise to him. And he went with it, because Cassavetes did nothing but throw him surprises on all the work they did together. I also knew John very well. Where Oscar Hammerstein was the mentor to Stephen Sondheim, John Cassavetes was my mentor. I worked on a couple of his productions as a production assistant, and he really checked in with me and kept in touch with me right until the time he passed. And Peter knew that John liked me. And because John like me, Peter, I think, liked me, and we got along great.

Amazing. I would love to ask you more about being John Cassavetes’ production assistant, I’m sure there's some interesting stories there.

Yeah, I got yelled at a lot by almost everybody, but that's okay!

West Side Story is out now in UK cinemas. The Empire Podcast arrives weekly on Fridays. Read more here__.