A frustration with his father's home movie style quickly developed into a passion for experimental filmmaking. A showman was born—and a resourceful one at that.

In 1989, Steven Spielberg directed two feature films — Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade and Always — in the same calendar year. Four years later, he pulled off the same trick again to even more astonishing ends with Jurassic Park and Schindler's List. The critical consensus as to why Spielberg could work so quickly and effectively pointed to his experiences with George Lucas on Raiders Of The Lost Ark or just the burning passion that infused Schindler. But longtime producer and friend Kathleen Kennedy has other ideas.

"He's remarkable in his ability in knowing how things cut together and to be able to previsualise what he intends. I think it comes from the fact that he started making movies at 12."

Spielberg's fascination with filmmaking began when, appalled by the shaky camerawork and skew-whiff framing of his father, the youngster took over family home movie duties. Quickly this transcended mere reportage. Spielberg would soon be organising and orchestrating the events, getting the family to do "just one more take" of putting the tent up or additional pick- ups on picnics. Asked to capture the family driving away on the start of their vacation, Spielberg gave them a close-up of the spinning hubcap pulling out to reveal the whole car — "My first glimpse of the Spielbergian touch and a hint of things to come," observed his mother. Indeed, it was the start of a childhood filmmaking career that has set a template for all wannabe directors since — step forward Dawson Leery — and one that Spielberg has been careful to give proper credence to over the years.

"I've been really serious about filmmaking as a career since I was 12 years-old. I don't excuse those early years as a hobby. I really did start then."

Aa an acned auteur, Spielberg made around 15 films, in so doing traversing practically every genre: westerns (The Last Gun), war flicks (Escape To Nowhere, Fighter Squadron), science fiction (Firelight) disaster films (The Last Train Wreck), film noir (er, Film Noir), horror (Scary Hollow), thrillers (Encounters) comedies (Steve Spielberg Home Movies, The Great Race) and political satire (Rocking Chair). Perhaps revealing a subsequently squashed avant garde side, he also made films about the esoteric nature of dreams. A "tone poem" about the toilet flushing and what happens when rain hits dirt — the Indiana Jones trilogy they ain't. The result of such a prodigious output is that Spielberg got a thorough grounding in every aspect of filmmaking: writing, storyboarding, shooting, editing, sound and publicity — a TV film crew even visited the set of WWII flick Escape To Nowhere. Unlike many filmmakers who come to movies immersed in film history and famous shots, Spielberg developed his own unique eye while still absorbing cinema which may well account for his striking, fresh visual sense.

Following his takeover bid as the family documentarian, Spielberg's first fictional use of the camera borrowed heavily from the first film he ever saw aged five, Cecil B De Mille's circus drama The Greatest Show On Earth (1952). Riffing on De Mille's spectacular train crash, Spielberg recorded his toy trains smashing into each other, mounting up the tension by intercutting the speeding engines with the faces of plastic figurines looking on in "horror". His sophomore effort, a western entitled The Last Gun, was a nine minute western made for an Eagle Scout Photography merit badge. Filmed at Arizona Steakhouse, The Pinnacle Patio, because it had a red stagecoach parked outside, Spielberg created the death of a cowboy by throwing a dummy packed with pillows over a cliff and smearing the rocks with tomato ketchup. The "oeuvre" was gathering momentum.

It seems from the get-go Spielberg's sense of cinematic ingenuity and showmanship were already intact. Filming Escape To Nowhere, with a cast of only 20 schoolmates, Spielberg doubled the number of soldiers by employing a relay system where kids passed helmets onto each after they had run through the shot. Some times things didn't go as planned: the Escape shoot was interrupted by the police who were investigating complaints that the Nazis were on the march with rifles. The mix up is astonishing considering Spielberg had attempted to dye white T-shirts grey in order to look like German uniforms but the process went pearshaped meaning, for the only time in history, the Nazis were on the offensive sporting "sky blue".

As much as Spielberg's childhood filmmaking exploits were about exercising an imagination running on overtime, they were also about fitting in. An outsider as a youngster, Spielberg used his moviemaking not only make friends but also to win over enemies: not only did shooting high school American Football matches inveigle the geekoid Spielberg into the jock crowd, but casting a notorious bully as a squadron leader in Escape To Nowhere saw Spielberg pacify a longtime tormentor. By the time he had reached 16, Spielberg had amassed a repertory of filmmaking mates to rival Altman and Allen.

To fund his mini-masterpieces, Spielberg drew on three sources of finance: his dad, whitewashing citrus trees against bug infestation at 75 cents a tree, and, aged 14, playing movie exhibitor by screening 16mm films in the family home in Phoenix. Programming popular children's fare of the time — Davy Crocket, King Of The Wild Frontier, Francis The Talking Mule — Spielberg ran off flyers and posters to market the screenings, enlisted his sisters to sell confectionery (popcorn, candy, Kool Aid, Popsicles) and, post every screening, grilled the audience about their reactions to the film — a precursor of what Hollywood now calls "Focus Groups".

At the same time Spielberg was lapping up the best of cinema at the Kiva Theatre on Main Srrect in Scotsdale. The thrills and, indeed, spills of the Indy trilogy and Jurassic Park were formed in a fast food diet of Z-grade westerns, Tarzan flicks, Our Gang, cartoons, bad monster movies and serials. The young Spielberg also lapped up more substantive pictures such as Huston's Moby Dick, Ford's The Searchers (which he parodied in an untitled six minute film) and Hitchcock's Psycho where Spielberg spent ages boring neighbourhood pals about "Hitchcock's deployment of the power of suggestion". The Kiva Theatre was also where Spielberg discovered David Lean, a cinematic touchstone that has remained throughout his career.

The convergence of Spielberg's Super 8 adventures and total immersion in movies came with Firelight. An ambitious two hour 15 minute science fiction epic — aliens kidnap surbanites to create a human zoo on their home planet — the film was born out of Spielberg's love of science fiction and a cub scout trip missed by Spielberg where the troop saw a blood red light in the sky. To make amends, he decided to create his own UFO extravaganzr.

"I remember knocking out a script by staying up for 24 hours," recalled Spielberg. "It was only the second time I stayed up all night long. The first time was in the Boy Scouts, reading MAD magazine and vomiting with laughter. I wrote a 140 page screenplay in those 24 hours. The ideas were coming out of my brain in what you might call stream of consciousness, as fast as I could type. I took it and went to a duplicator and made five or six copies. A week later I began making Firelight."

Elements of Firelight would later be used in his 1977 Sci-fi epic Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Filmed mainly around the Spielberg home (a red light was hooked up to warn the neighbours to keep quiet during filming), it was a production plagued with problems — the original leads Carol Stromme and Andy Owen quit after two weeks — but became Spielberg's most audaciously realised project to date. Displaying superb negotiating techniques, Spielberg not only persuaded the local hospital to let him film in a room full of medical equipment but also blagged a jet from American Airlines to film a brief shot. The film was also technically a step up for Spielberg with actors post synching (frankly, stilted) dialogue and the director composing the score on a clarinet which was transposed by his mother (a concert pianist) so it could be performed in all its glory by the High School band.

For the film's premiere on March 24, 1964, Spielberg pulled out all the stops, hiring the local cinema, placing giant arc lights outside, even arriving with his cast by limo. The film turned a profit of $100 on the night — Spielberg's biggest hit to date — but artistically, Spielberg believed it left a lot to be desired. "It is," he said later, "one of the five worst movies ever made."

Spielberg's university years are among the least documented in the director's increasingly public life. Despite his Super 8 back catalogue, his grades were not good enough to take him to an established film school so he enrolled at California State University, partially as a way to avoid the impending Vietnam draft. Nominally he was there to study English but what he really majored in was movies: "I did nothing except watching movies and making movies."

With his Academic experiences becoming increasingly frustrating — he received a C-grade on a TV Production module — Spielberg continued to generate his own movies: a frantic farce called The Great Race in which a young student chases a girl around a college was very much in the zany silent era mode. Encounters was a more sophisticated 16mm exercise in Hitchcock twistology in which a sailor is attacked by a mysterious thug, the assailant's plan later revealed as a plot to kill his own twin brother. While other teens were protesting on the streets about Vietnam, Civil Rights and "The Man", Spielberg was to be found safely ensconced in LA arthouses.

"Anything that wasn't American impressed me," says Spielberg of his cinematic tastes at that time. "I went through a period of Bergman. I think I saw every picture Ingmar Bergman made. It was wonderful! You'd go to the theater and see all the Bergman films one week. You'd go to the same theater the next week and see... Maybe Jacques Tati. I loved him! Truffaut is probably my favourite director. I saw all the French New Wave Films at school."

Despite his veneration of serious, challenging filmmakers, no studio would take Spielberg's short films seriously. So, through money chipped in by his father and wannabe producer Chuck Burris, the director upped the ante and started work on his first 35mm short. A tale about adrenaline junkie bicycle racers, Slipstream was designed as an exercise in directorial showmanship. Shooting over several weekends during 1967, the plug was pulled when the production ran out of funds — footage appeared in Citizen Steve, a film made for Spielberg's birthday by ex-wife Amy Irving— but some lasting acquaintances were made: in the course of searching for a cameraman, Spielberg hooked up with fellow young turk Allen Daviau, who would later become the cinematographer on E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, The Color Purple and Empire Of The Sun.

For his next effort, Amblin', Spielberg got more calculated. "I wanted to shoot something that could prove to people who finance movies that I could certainly look like a professional moviemaker," Spielberg observed. ''Amblin' was a conscious effort to break into the business and become successful by proving to people I could move a camera and compose nicely and deal with lighting and performances."

Empowered by the financial clout of producer Dennis Hoffman — who stipulated that Amblin' must feature no dialogue, be lensed at his Cinefx studio and feature music by his pop protege October Country — Spielberg's yarn of a young man (Richard Levin playing a square Spielberg clone) hitchhiking across California was built on the tenets of youth culture — drugs, sex. the open road rebellion — yet suffused with a wariness of hippiedom that would have been shared by the studio execs who could grant him a job. What really counted, though, was Spielberg showing off his directorial arsenal. On his first day of filming, Spielberg started with a complicated tracking move around lovers making out by a bonfire which used up four times his daily film stock allocation. The following week long shoot saw him vomit before every day.

But the queasiness was worth it. Opening alongside Otto Preminger's Skidoo — Amblin's tagline read "He and she were thumb trippin'. They had the makin's... and the tail-end of the summer", possibly the worst tagline in poster history — the 26 minute short garnered strong reviews, showcase screenings at the Venice and Atlanta Film Festival and looked a shoo-in for a Best Short Film Oscar nod. When the latter didn't happen, it was probably less to do with Spielberg's proficiency and more to do with the film's brief endorsement of spliff smoking as " fun": one of the trade ads promoting Amblin' as an Oscar contender misguidedly featured a joint and a bag of marijuana. Still, the upside was that Spielberg got an early blooding in Oscar disappointment, something the next 30 years would see quite a bit of.

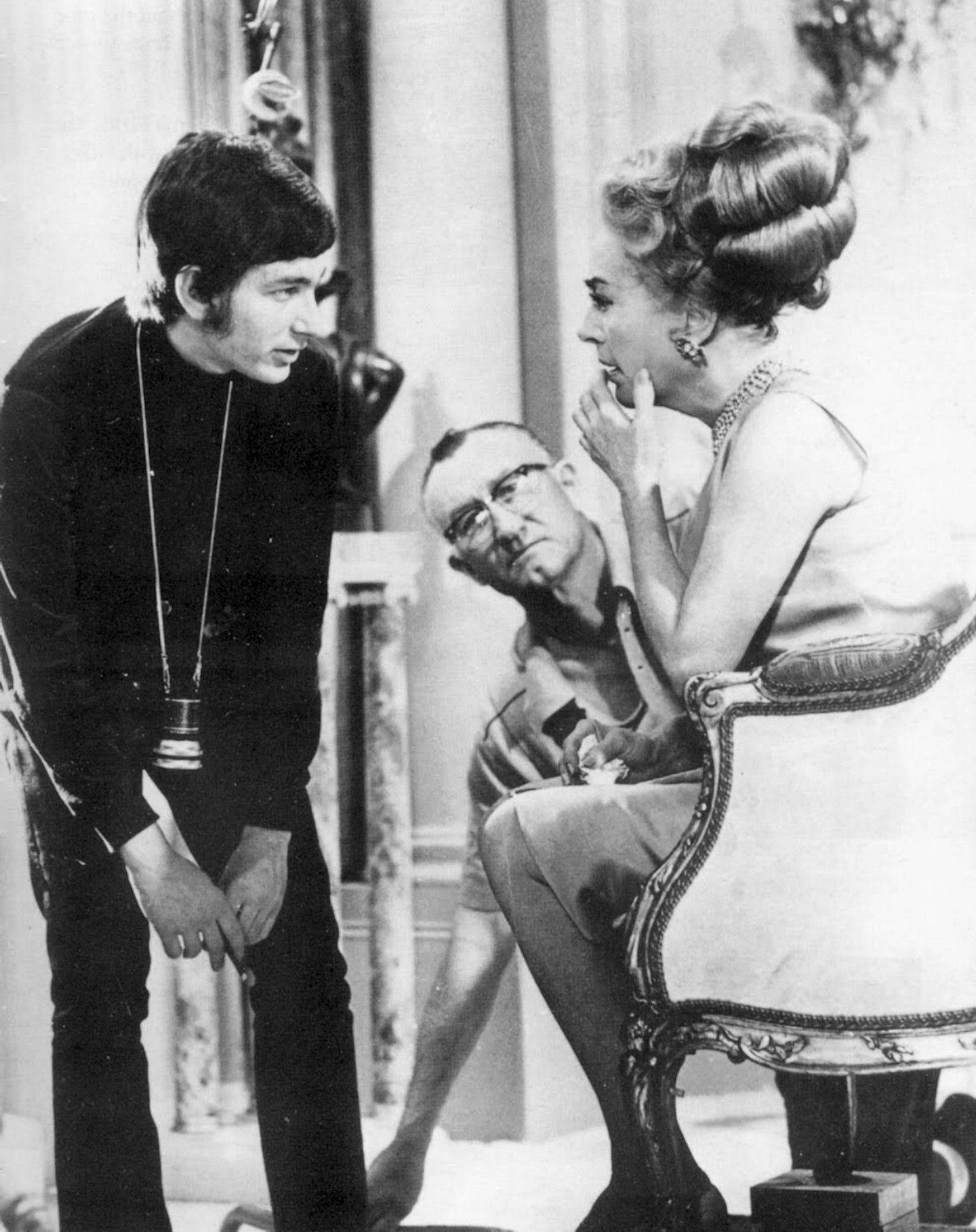

The young Spielberg has Joan Crawford's undivided attention.

PT 109 was a jingoistic WWII adventure released in 1963 about the exploits of John F. Kennedy (Cliff Robertson) as a young Navy Lieutenant in the US Navy. Directed by Leslie H. Martinson, it has no place in movie history whatsoever except that it marks the first time Steven Spielberg, aged 16 , set foot on a Hollywood soundstage. Ironically, it was Stage 16 at Warners, the very stage some 30 years later he would direct dinosaurs to superstardom in Jurassic.

Before he became a fully fledged professional filmmaker, Spielberg would spend a lot of time loitering around film sets. He had met Universal Studios Librarian Chuck Silvers while still in High School and Silvers took an immediate liking to the enthusiastic hopeful. During his Long Beach days, Silvers facilitated Spielberg to spend three days a week at Universal watching various films and TV shows in production. Observing the filming of an episode of Bob Hope Presents The Chrysler Theatre, Spielberg was noticed by John Cassavetes and asked to coach the actor in his performance — Spielberg later worked as an uncredited production assistant on Cassavetes' Faces. Furiously networking, the precocious kid "took meetings" with Charlton Heston, Cary Grant, Rock Hudson and director William Wyler but it was longtime ally Silvers who proved the ace in the hole. Having been blown away by Amblin', Silvers immediately arranged for the short to be screened for Sid Sheinberg, the then VP of Production for Universal TV. Equally knocked out by Amblin', Sheinberg called the kid into his office and offered him a seven year contract starting at $275 a week. Spielberg hesitated, replying he technically hadn't finished college yet. Do you wanna graduate college," barked Sheinberg who later resuscitated Spielberg's career a number of times during his TV years, "or do you wanna be a film director?"

There really was no contest. As Spielberg plied his way through TV hell, ideas for feature films were consistently germinating in his head. First pitched in 1969, The Sugarland Express (formerly known as Carte Blance, American Express and Sugarland) followed a young couple (Goldie Hawn, William Atherton) who kidnap a police officer in order to retrieve their baby boy from foster parents. The movie had a rocky road to production, stalling at both Universal and United Artists, finally going before the camera on January 15, 1973. After years of amateur experimentation massaged by small screen discipline this was the moment Spielberg had been waiting for and he wasn't about to squander it.

"I was thinking 'Well, let's take it easy,'" recalled producer Richard Zanuck, '"Let's get the kid acclimated to this big stuff.' But when I got there the first day he was about ready to get the first shot, and it was the most elaborate fucking thing I've ever seen in my life. I mean tricky: all-in-one shots, the camera going and stopping, getting in and out. But he had such a confidence in the way that he was handling it."

In the end Spielberg's technical dexterity may have failed to find a large audience but something else was brewing in the air. The Sugarland Express was co- scripted by USC film school graduates Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins, part of a band of young filmmakers who were set to put a rocket up the arse of the old guard. Despite emerging from the Universal establishment, Spielberg had the right credentials to join the club — flared trousers, bad hair, passion for movies and boundless precocious talent — and soon took his place among a new wave of tsunami proportions. The barricades were coming down. Revolution was just around the corner. Or so they thought.