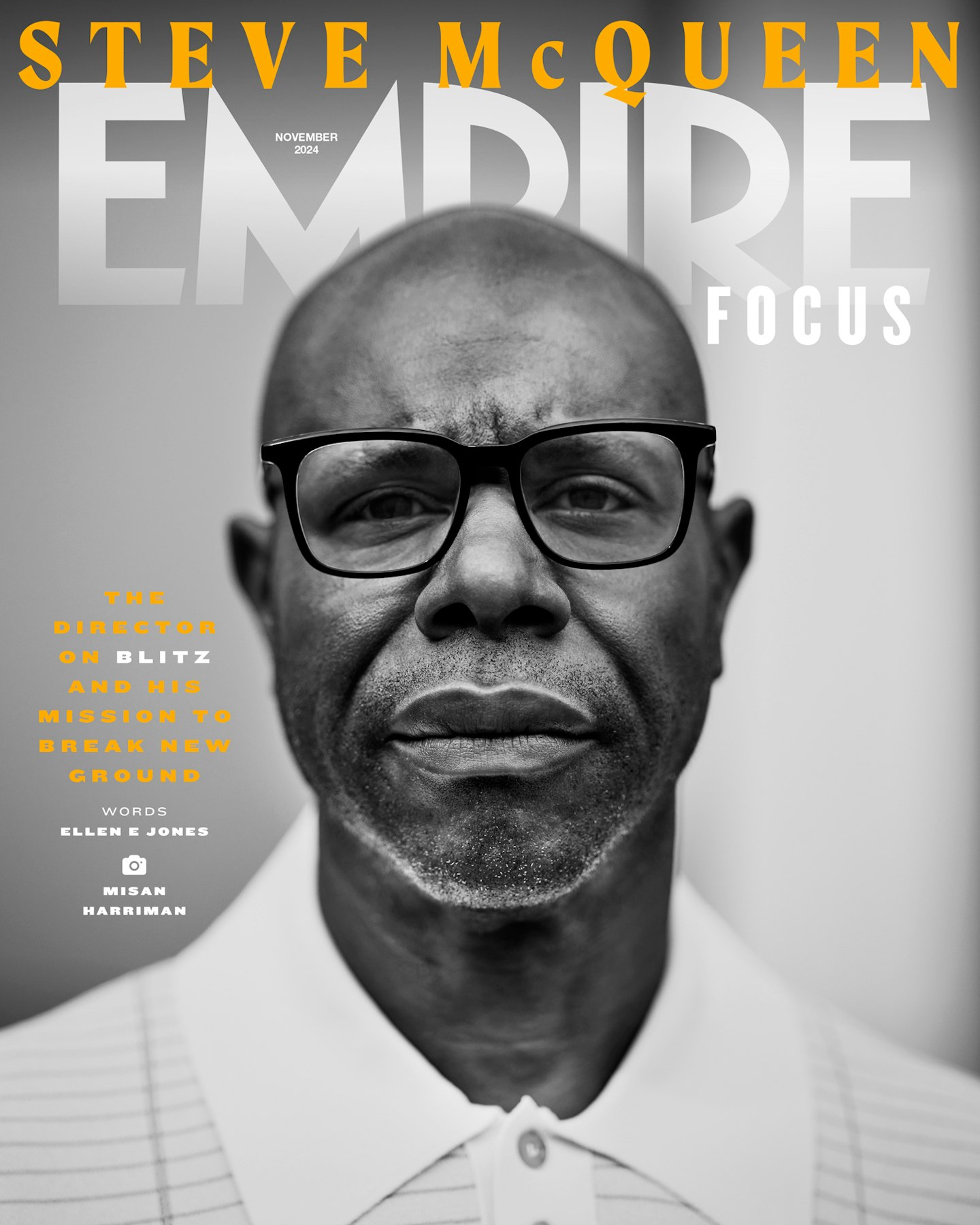

With his new World War II drama Blitz, uncompromising filmmaker Steve McQueen is once more tackling weighty, vital material. He tells us about his ongoing mission to break new ground…

Here’s what you need to know about Steve McQueen, as a man and as a filmmaker: he will not waste your time. Not with false modesty, nor with empty boasting. Not by suffering fools or flattering royalty. This is sometimes mistaken for brusqueness. It isn’t. It’s a guarantee that when a single shot of a priest conversing with a prisoner lasts 17 minutes and 11 seconds (as in 2008 feature debut Hunger), or when his 2023 Holocaust documentary Occupied City takes four hours and 26 minutes (not including interval), every moment is necessary and accounted for.

It’s this disciplined focus on what McQueen emphatically calls “the work... The W-O-R-K” which has enabled the 54-year-old to frequently pull off seemingly impossible feats over the course of a still relatively young filmmaking career. There are the oft-cited accolades — the Turner Prize, the Oscar, the Golden Globe, the BAFTAs and the knighthood — but also a host of, when you really think about it, more impressive achievements. This is the man who disproved decades of received industry ‘wisdom’ on box-office viability with 2013’s 12 Years A Slave; who magnificently crowned a year of #BlackLivesMatter uprising in 2020 with Black British opus Small Axe; who, in the aftermath of tragedy, secured a grieving community’s permission to shoot the remains of Grenfell Tower from a helicopter. And who else would think to adapt a sophisticated Hollywood neo-noir from a 1980s ITV drama (as he did with Widows)?

McQueen’s latest, Blitz, is another compendium of cinematic wonders, both spectacular and subtle; a scrupulously historical epic about that much-claimed and contested period between September 1940 and May 1941, when Britain endured sustained bombing from Hitler’s Luftwaffe. But this is not the Blitz of Faragist myth-making or stiff-upper-lip wartime propaganda. Rather, it’s seen through the eyes of young George (Elliott Heffernan), a mixed-race, east-London evacuee, and his spirited single mum Rita (Saoirse Ronan), who along their way encounter a Dickensian gallery of friends and foes played by Paul Weller, Kathy Burke, Stephen Graham, Harris Dickinson, Hayley Squires, Linton Kwesi Johnson and more.

For viewers, Blitz offers the hyperreal sensation of living through the past, only in our present. And it arrives when the nation is once again searching for a renewed sense of identity. Because, as ever with Sir Steve, the timing is perfection.

How did Blitz begin?

When did I start thinking about this? Goodness gracious! Well, London is a strange kind of place, with all this evidence of the past, but it’s not spoken about. I remember growing up in the ’80s, and there were so many things going on in these derelict buildings, but you never thought about why they were there, about the Blitz. You just thought, “Okay, this is where you can have an alternative space, have a gallery.” I just wanted to investigate that, really. And then, while doing research for Small Axe, I found this picture of this Black child, this little boy, whose overcoat was too big for him and his suitcase was too big, and I thought, “Who’s that guy? What’s his story?” Then things unfolded from there.

What kind of historical research did you do?

Oh, I researched like crazy, wanting to know everything about that period, and lot of the true stories from our research are in the picture. For example, Ife (the Nigerian air-raid warden, played by singer-songwriter Benjamin Clementine), that’s a true story. Ita Ekpenyon used to patrol the Marylebone area, and that speech he gave in the shelter, with these parallels to now, the [August ’24] riots, of white English people trying to divide? That really happened. I didn’t have a crystal ball when I was writing, but I think that’s the nature of art. The craziness of what Britishness, Englishness is; that’s being put into question again now, as it was back then. There are so many parallels that one could talk about as far as this picture is concerned. It’s also about war, and let’s not forget what’s going on elsewhere in the world, in Ukraine and in Palestine.

As well as stars and screen stalwarts, the Blitz cast includes first-time actors and musicians. What was your approach to casting?

Elliott Heffernan had never acted before. We auditioned a lot of people, and when we saw him, there was just something about him. He wasn’t cute, at all; he was real. You couldn’t read him that well, but also he reflected you, in a way. He’s like a Buster Keaton; there’s presence in his absence. Saoirse, she’s one of the best actresses of her generation, of course, but also her generosity with Elliott, [from] her having also been a child actress. With Paul Weller, I just thought he’s got such a great face, and you don’t write those songs and perform those songs without being able to sort-of act. He needed some convincing, but he’s a wonderful grandfather, and also the chemistry between Paul and Elliott and Saoirse was so beautiful. I didn’t make that. That’s just how they were together.

Blitz’s colour-scheme seems a lot more vivid than the typical World War II period drama...

Absolutely. Rita likes fashion, she likes her clothes and she was keeping her sexuality, her femininity; that was her resistance. She wasn’t going to change, or dampen down for anyone. And fuck Hitler and the Luft- what is it?... Lufthansa? Fuck them.

Luftwaffe. Not the Lufthansa airline. They’re alright, as far as we know.

Yeah, Luftwaffe, fuck them, because, you know, one has to keep one’s humanity. So with [costume designer] Jacqueline Durran and [production designer] Adam Stockhausen, it was basically looking at the archive. There was an amazing American woman in London at the time, Lee Miller, who shot a lot of stuff on Super 8 and that was so beautiful to see. Never forget — when the war started, it was a beautiful summer’s day in September. So it is what it is; one is not making it up. It’s just interesting that people usually dull it down. It’s like, on the set of 12 Years A Slave, I remember saying to someone, “Y’know, sometimes the most horrible things happen in the most beautiful places.” But, I’m not gonna get my cinematographer to skew the angle or focus or whatever bullshit. Nah. It is what it is. War is perverse.

"It’s not about history; I’m interested in stories. That’s why I’m a filmmaker."

Were you also thinking of any British 1940s wartime films as visual reference points?

No, because I want to start from scratch, [otherwise] it becomes cliché. And I’m always interested in finding out what the thing is for myself. I mean, when I saw that photograph of that Black child, have I ever seen that person before, ever in my life? In a picture? Or in a movie? No. So let’s start from scratch. I don’t trust anything anyone tells me, I’m going to find out for myself. That child exists. [But we were told] we didn’t exist. On these munitions lines [in the movies], Black women didn’t exist. But they did exist.

You’re married to a historian and you often make films about historical subjects. Is a filmmaker a kind of historian?

No, it’s not about history; I’m interested in stories. That’s why I’m a filmmaker. I want bums on seats. I want people to engage. I want people to be thrilled, to be joyous, to be tearful, to be scared out of their wits. But at the same time, I want to hold their hand and take them on the journey... But also this is unfinished business, so it’s not like it’s history. It’s unfinished history! People have not dealt with the trauma of the Second World War. They’ve put these sort of memorial plaques up, but underneath, it’s cracked. I mean, certain people are recognised, certain people are not. I didn’t want to look at Churchill. I didn’t want to look at Roosevelt. I wanted to look at this kid George. I wanted to look at Rita. I want to look at Ife. I want to look at Mickey Davies [played by Leigh Gill in the film], the small chap who ran the shelter in Stepney. He was a real person, an optician and one of the pioneers of the NHS. How the hell did we not know who Mickey Davies is? There should be a fucking statue of him somewhere!

Is it true that you discussed the idea for this film with Princess Anne? How did that conversation go?

Yes. I was getting my knighthood and I told her I was making a film about the Blitz. She goes, “Eaughhh” (He approximates an aristocratic vowel sound, expressive of mild surprise). Y’know... she was engaged! She was engaged and engaging.

Are your feelings about receiving that knighthood complicated by your awareness of the history of the British Empire?

I said, “Hmmmm...” but [ultimately] I thought, “Y’know what? This is my country, and if they want to give me one of the highest accolades, I’ll ’ave it, thank you very much!” And I’ll use it for what I use it for — for making the work — because that’s the only thing it’s good for, and that’s about it. End of story.

Is there any connection between your time as Britain’s official war artist and this film?

Yes. That’s the thing that pushed it to the fore. In 2006 I was embedded with the troops in Iraq, [I was] in an Apache helicopter going up to the oil fields and so forth. I was around these troops who were from, you know, Glasgow, Swansea, Plymouth, Newcastle, Surrey, and it was just wonderful to be around this group of guys with all different regional accents, just talking about stuff. There was a sense of national camaraderie. It’s like being in the English football team, I imagine; that sense of togetherness. And it’s unfortunate that one of the few times I’ve ever had that feeling was in the context of a war. I think that carried through in understanding the Blitz better, and the whole idea of being bound together because of the situation you find yourselves in.

Is it true you weren’t able to complete the work that you wanted to at that time?

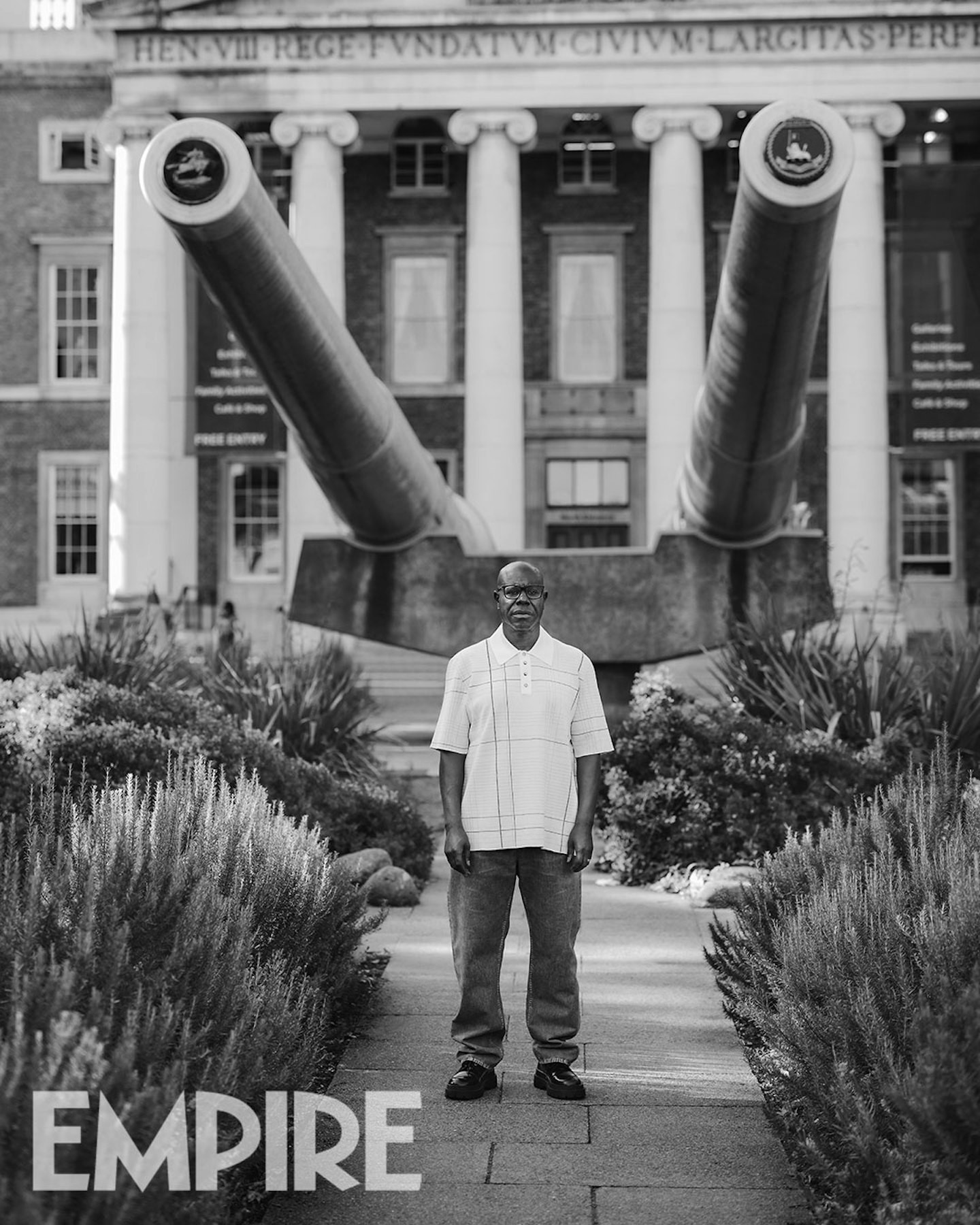

What I wanted to do was make stamps of the individual soldiers who had died; actual stamps that you could put it on envelope and mail. The idea was that they would go within the bloodstream of the country so that people’s entry into this war was not through the media, but through the everyday, and these individuals who apparently fought for you — for Queen and Country — were personalised. You’d receive them not as a number, but as an individual on your doormat. At that time, the only people who could appear on the stamp as a portrait were members of the Royal Family, or dead. I thought, “Who else is more deserving person than a dead soldier?” But the Ministry of Defence weren’t into it. We put something together to present to the Royal Mail and they were not helpful. So I wrote to the next-of-kin for permission and 95% agreed. I made this work called ‘Queen and Country’, which consisted of a facsimile of these stamps in a vitrine and it’s on permanent display at the Imperial War Museum right now. One day, maybe [the real stamps] will happen…

So do you see Blitz as a continuation of that official war-artist commission?

Not really, but I think I witnessed, experienced, war in a way which the majority of people will never do. I didn’t gain an understanding of war through the media, but through being on the ground. What was interesting for me, as a civilian, is what it means for individuals. I think that maybe goes back into Blitz, the people who have to suffer in the midst of all this stuff — just as they are now. It is the perversity of that situation, really. You can see that Rita’s making bombs, and she’s scurrying away from them to the shelter. Also, munitions factories gave these women liberation, through that sort of union of other women. Again, the unfortunate situation of war can actually create other things. I think my movie — not to sound corny — it’s about love. That’s the only thing worth living for, and it’s only thing worth dying for. Nothing else. That’s what I wanted to illuminate.

There’s a lot of thrilling spectacle in Blitz, as well as the intimate human story. What was the most challenging to shoot?

Well, the flooding of the Underground station, that was an Adam Stockhausen achievement, because we couldn’t, of course, flood a real London Underground station, so we had to build it all. They wanted to cut the budget, and I said, “No, we’re not doing that.” I had to find money, move things around. And it was absolutely thrilling to shoot. I mean, the things that were so-called ‘difficult’ weren’t difficult, because, listen: we’re British, meaning, we make do. I’m smiling, just because it was so wonderful [on set], seeing everyone see themselves in an epic picture — a British epic. The only time you have a British epic is when it’s colonial folks on A Passage To India or getting Out Of Africa, all that bullshit. So this was a joy. What was the challenge? There weren’t any. It was just, “Let’s get on with it!”

"I’ve always wanted the weight. Give me the weight. Give me the burden."

In your career you’ve frequently pulled off the apparently impossible. Has there ever been a project that’s defeated you?

No. (Looks baffled by the question) You don’t give up. Sometimes I’ve been in situations and thought to myself, “What the fuck am I doing? Why am I doing this? What am I doing?” But you just push on through and come to the other side. Of course, there’s a lot of difficulties, a lot of conversations and complications, but I want the burden, you know? I want the weight. I’ve always wanted the weight. Give me the weight. Give me the burden.

You like heavy subjects, don’t you?

Well, it’s not that I like heavy subjects. No, don’t get me wrong. I’m not a masochist. It’s just that it’s the right thing to do. It’s about the work at the end of the day. The W-O-R-K. Is it going to be any good? It’s focused on the work, not the suffering. I’m not interested in if it’s difficult of not. I couldn’t care less. What is the work that you are doing? That’s it. It could be a love story. It could be a comedy, but is it any good?

Small Axe was such a milestone, both in how it asserted that Black history is British history and in how it showcased Black British talent. Do you keep an eye on what’s going on in Black British film and TV since?

Yes, I do. But the fact of the matter is, where are they? I mean, it’s so disheartening. It just hurts me so much, when I think of those people, those actresses and actors in Small Axe — particularly Black actresses — where are they? Amarah-Jae St. Aubyn from ‘Lovers Rock’? Where is she? She should be a movie star. But I’m determined to help who I can help, and get things going. Because, also, these stories are amazing! There are great films waiting to happen — exciting, vibrant, dynamic.

You’ve previously utilised a child’s-eye view in scenes from Hunger and Small Axe’s final film ‘Education’. Do you find memories of what it feels like to be a child easy to access?

Yes, because I’m still processing it! (Laughs) Thinking about, “Who am I? Why were my parents like that?” Also, to be a pre-pubescent child is very interesting, because there’s a certain innocence, and a certain lack of ambiguity. When you get older, you start compromising and you can be compromised. When you’re a kid, there’s good, there’s bad and that’s it. When you grow up — as a Black child, particularly — you have a sense of justice from a very early stage because you’re confronted with so much injustice, y’know? And I like that [opportunity] to refocus our adult eyes through this child’s eyes. Because sometimes we forget who we are, where we came from and what we can represent.

What was it like for you growing up with the same name as the other Steve McQueen?

Well, my name came from Steven in [US soap] Peyton Place. My mum was a big fan. And then, when I was born, the nurses were all, “Oh, how’s Steve doing?” My mum was like, “It’s Steven, not Steve.” But Bullitt came out in ’68 (January 1970 in the UK) and I was born in ’69. I remember going to see The Magnificent Seven with my father, because Westerns in the West Indian community were huge. We’re talking mid-1970s, at the Hammersmith Odeon. I remember the carpeted walls, touching them — and hearing that theme tune and then you see your name come up on screen... That was amazing. People ask me if I ever thought of changing my name, but... I don’t get into this fame business, to be honest. That’s when you get stupid.

How have you changed as a director since your debut, Hunger, in 2008? Have you grown in confidence?

Hmmm... I think I was pretty confident when I did Hunger. You know what it is: it’s about knowing what you don’t want rather than what you want. When you know what you don’t want, your field of reference is much smaller, so therefore you get on with it. More things are possible, because there’s no time-wasting. I don’t do coverage. People say I shoot quick. I didn’t know I was quick, because I’ve never been on a film set other than my own. And I’ve learned collaboration is the key: to work with people who you love, and they love you. There’s this beautiful thing where you’re getting people high and you see magic happen and you can’t wait to go back in the next day. And also, the fact of the matter is, when people are themselves, it’s much more of a laugh.

Blitz comes to UK cinemas from 1 November, and streams on Apple TV+ from 22 November.

Originally published in the November 2024 issue of Empire. Photography by Misan Harriman.