The article first appeared in issue 184 of Empire magazine.__Subscribe to Empire today{

THE MUCH PUBLICISED FALL OF US ENERGY GIANT ENRON sent shock through the corporate landscape. Marked by its political affiliations with the Bush administration, the huge Texas corporation had grown into America’s seventh largest company, yet revelations of concealed debts saw it nosedive into the blackness of bankruptcy. Employees lost pensions; the company lost $4.7 billion. But down the list of utilities where Enron secreted investments, the limited partnerships monickered JEDI LP and Chewco Investments LP must have made thirtysomething financial analysts smile. Perhaps the first time that Star Wars and financial disaster have co-existed in the same universe, it is proof that the Force, like Coca-Cola and Keith Lemon, really does get everywhere (the dodgy double dealings obviously a dark side thing.)

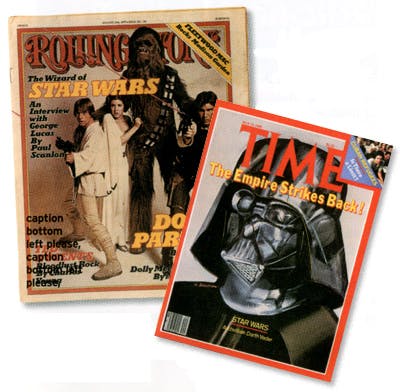

The Star Wars effect is seismic, sharing a global currency akin to The Beatles: both span generations, both stand in for a specific moment in time (mid ‘60s/late ‘70s) yet have survived the vagaries of fashion to thrive outside their heyday. Both also inspire rabid devotion – and all this in the face of really terrible hairdos. For any media-conscious person, a Star Wars reference will present itself at least once a day, every day. Turn on the TV and The Simpsons will be riffing on a “No, I am your father” gag. Log onto the Internet and count how many pop-ups and adverts are ‘inspired’ by that infamous opening crawl. Take the lift up to your accounting department and see how many geekoids have customised their workstations with Bib Fortuna pencil holders or Java the Hutt coffee mugs. Star Wars’ influence is viral, spreading out from the movie business into every aspect of cultural life.

So, if you want a sporting reference, try the fact that the Boston Red Sox use the Star Wars sobriquet ‘the Evil Empire’ to describe their arch rivals, the New York Yankees. If you want a porno reference, Sky’s Day Off sees the eponymous heroine and her latest conquest engage in combative gonzo-style rumpy pumpy: to establish superiority, the pair engage in a lightsaber battle, with dildos rather than Jedi weaponry producing the energy beams. From providing the name to a Strategic Defense Initiative, to the theme ride at Disneyland, to rap lyrics (“C.O.P has an APB out on Chewbacca” – ‘The Beast’, The Fugees), Star Wars hasn’t just surfed the zeitgeist, it has shaped, defined and – particularly this week as Lucasfilm have been bought out by Disney – swamped our cultural lives with more zeal than you could imagine. And you can imagine quite a bit.

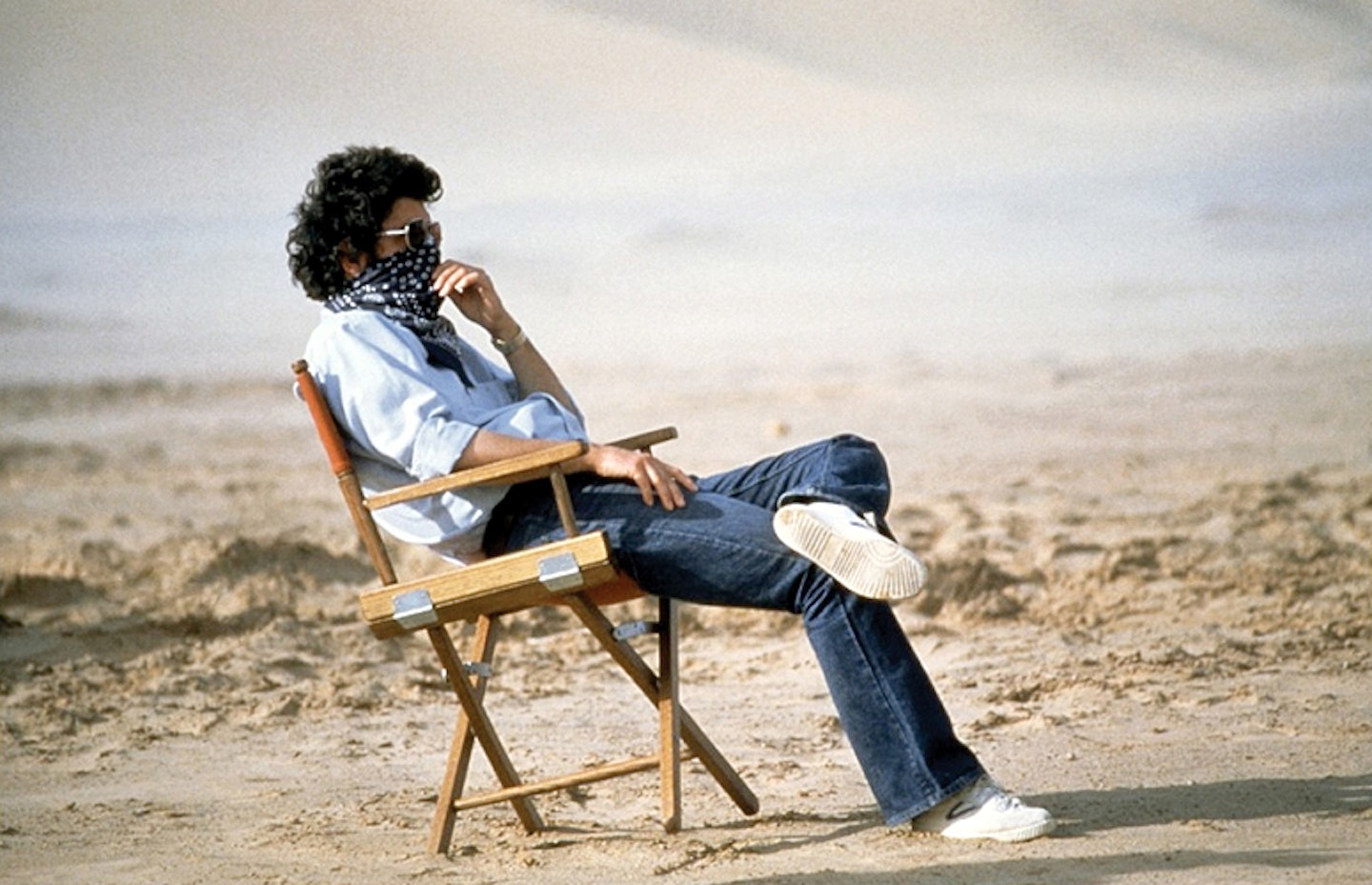

%20%20*Like%20The%20Beatles,%20Star%20Wars%20inspires%20devotion%20in%20the%20face%20of%20bad%20hairdos.*%20%20%20**ON%20MAY%2023%201977,**%20%20George%20Lucas%20was%20a%20broken%20man.%20Mixing%20the%20foreign%20language%20version%20of%20Star%20Wars%20%E2%80%93%20or%20Stjerne%20Krigen%20(Norway),%20La%20Guerre%20Des%20Etoiles%20(France),%20Tahtien%20Sota%20(Finland),%20La%20Guerra%20De%20Las%20Galaxias%20(Spain),%20Guerra%20Nas%20Estrelas%20(Brazil)%20%E2%80%93%20had%20seen%20the%20two-week%20unbroken%20run%20of%2018-hour%20days%20finally%20take%20its%20toll.%20Emerging%20from%20the%20LA%20dubbing%20theatre,%20Lucas%20craved%20a%20burger%20and%20a%20break.%20The%20short%20drive%20to%20Hollywood%20Hamlet,%20a%20dinky%20little%20joint%20opposite%20the%20world-famous%20Grauman%E2%80%99s%20Chinese%20Theatre,%20was%20slowed%20first%20by%20intense%20traffic%20and%20then,%20more%20alarmingly,%20by%20hordes%20of%20people%20teeming%20the%20streets.%20Rounding%20the%20corner,%20Lucas%20saw%20%E2%80%98STAR%20WARS%E2%80%99%20in%20giant%20capitals%20above%20the%20marquee%20and%20a%20massive%20crowd%20baying%20for%20banthas.%20It%20had%20slipped%20his%20mind%20that%20his%20labour%20of%20love%20went%20public%20today%20%E2%80%93%20the%20blocks%20were%20truly%20busted.While%20Lucas%20immediately%20took%20off%20for%20a%20prearranged%20holiday%20in%20Hawaii%20with%20buddy%20Steven%20Spielberg%20%E2%80%93%20apparently%20they%20talked%20archaeology%20%E2%80%93%20the%20way%20movies%20were%20made%20and%20marketed%20was%20transformed%20irrevocably.%20From%20merchandising%20(Star%20Wars%20changed%20the%20size%20of%20action%20figures%20from%20the%20standard%2012%20inches%20to%203%20%C2%BC%20inches%20because%20the%20old%20size%20meant%20any%20toy%20spaceships%20would%20have%20had%20to%20have%20been%20about%20five%20feet%20long)%20to%20state-of-the-art%20soundsystems,%20from%20summer%20release%20scheduling%20patterns%20(May%20suddenly%20became%20the%20optimum%20month%20to%20release%20a%20crowdpleaser?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

But, as has been outlined ad nauseam by the likes of Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Lucas’ magnum opus was to have a more insidious effect on the way Hollywood operated. The argument goes like this. The unprecedented success of Star Wars (and two years earlier, Jaws) created a hothouse atmosphere in Hollywood which meant blockbusters became the dominant form of life. Smaller films by the likes of Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese and William Friedkin that had once occupied the middle ground were now crowded out, with innovative form and edgy content usurped by empty spectacle and moral certainties. Not to put too fine a point on it, Star Wars had killed The Last Golden Age of Hollywood and Lucas was seen at the crime scene with a smoking gun.

The counter-myth (to use a Oliver Stone-ism) shakes down like this. It is undeniable that Star Wars’ success put the whizz-bang thrill machine front and centre – its rapid pace and zappy graphics also influencing the emerging MTV channel and computer games, more entertainments that critics like to pronounce as the death knell of cinema. But just as ageing racer John Milner in Lucas’ American Graffiti lamented that “rock’n’roll has been going downhill ever since Buddy Holly died,” so the ‘Star Wars murdered movies’ conspiracy theorists, perhaps blindsided by the saga’s impact, haven’t really studied the evidence. For starters, as the unadulterated genius of Badlands, McCabe & Mrs Miller and Mean Streets were being lapped up by the cognoscenti, the masses were enjoying Earthquake, The Towering Inferno and The Spy Who Loved Me, blockbusters every bit as programmatic as Star Wars but with none of the charm. ‘70s Hollywood was changing anyway, the period of creative freedom facilitated by the end of the studio system coming to an end as behemoth conglomerates took control of Tinseltown at the close of the decade. The days of wine and ambiguous freeze-frame endings were probably numbered, Star Wars or no Star Wars.

It doesn’t take into account either the sweep of directorial seppuku that took place post-1977. Altman’s Quintet is the most indulgent kind of science fiction, while Friedkin’s Wages Of Fear remake Sorcerer smacks of directorial ego run rampant. Terrence Malick packed it in after 1978, and Peter Bogdanovich, Brian De Palma and Bob Rafelson all hit a vein of uneven form, a slew of misfires contributing to their own downfall. Nor does it register the fact that the success of Star Wars allowed certain smaller films to live. It is doubtful that, without Lucas’ box office alchemy, Fox could have patronised Altman’s career in the late ‘70s.

If Lucas’ experiments with digital cinema has resulted in the death of film in a literal sense, no film or filmmaker has done more to sharpen cinema’s bleeding edge. He famously yanked special effects out of the static camera, models-on-strings dark ages and into the Industrial Light – motion control and bluescreen technology creating a massively broadened FX palette and a new sense of what was possible. EditDroid was the forerunner of Avid, the digital editing system that revolutionalised the way the films are cut. THX sound systems paved the way for a new definition of aural sex, inventing, to a large extent, the concept of home cinema.

While the number of filmmakers who were inspired by the moment that the Star Destroyer flew over the camera is legion – James Cameron, Peter Jackson, Ridley Scott, Bryan Singer, Roland Emmerich and JJ Abrams among them – Lucas’ own payback is often misrepresented. Sure, there was Howard The Duck and Radioland Murders, but there was also his (uncredited) patronage of Body Heat and the Francis Ford Coppola co-production Tucker, as well as his financial support of Akira Kurosawa (Kagemusha), Godfrey Reggio (Powaqqatsi) and Paul Schrader (Mishima) – the last two exactly the kind of American movies Lucas was supposed to have killed off. And we haven’t even got to the man with the hat.

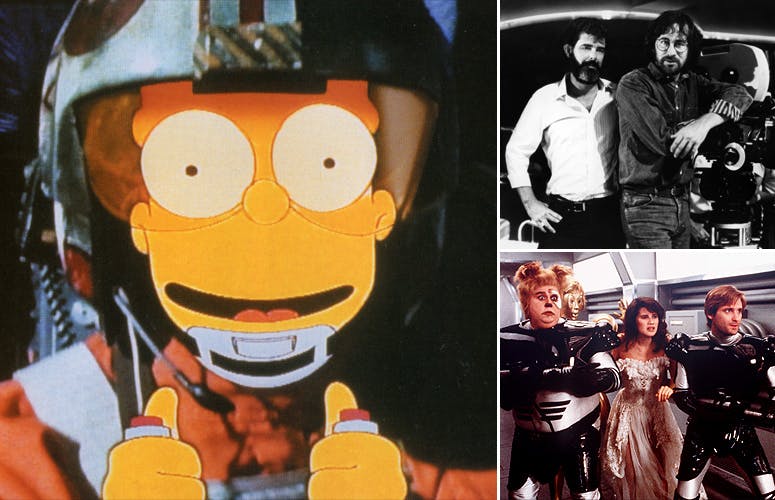

%20*Bart%20of%20target:%20The%20Simpsons%20is%20stuffed%20with%20Star%20Wars%20references%20(left).%20George%20Lucas%20and%20Steven%20Spielberg%20changed%20the%20way%20movies%20are%20made%20forever%20(top%20right).%20Aboard%20Dark%20Helmet's%20Prison%20Zone%20in%20Mel%20Brooks'%201987%20Star%20Wars%20spoof%20Spaceballs%20(bottom%20right?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

FOR ALL THE TALK OF IT HERALDING THE DEATH OF MOVIES, Star Wars itself was once facing extinction. Post-Jedi, with no future Episodes on the horizon and the TV spin-offs (the infamous Holiday Special, the Ewok TV movies, the cartoons) failing to convince that the franchise could work as a small-screen proposition, the series was on its last legs. Then came the toy revolution. An entire generation who had grown up with cardboard Death Stars and blue-edged trading cards had now entered the workforce. They had disposable income with which to create the warm glow of their childhood by furnishing their bachelor pads with Star Wars replicas, even if those had undergone a makeover – in 1995 the rebranded Power Of The Force line imagined Luke, Han et al. with buff bodies and toned muscles that wouldn’t look out of place in a San Francisco gym.

After Star Wars, Lucas financed exactly the kind of small films he was supposed to have killed off.

After Star Wars, Lucas financed exactly the kind of small films he was supposed to have killed off.

Even more important than the action figures were the books. In 1991-93, against all the literary odds, a trilogy of Star Wars spin-off novels by Timothy Zahn – Heir To The Empire, Dark Force Rising, The Last Command – topped the New York Times bestsellers list. The books kickstarted a plethora of ‘Expanded Universe’ fiction, which has sated the fanbase in the gaps between movies. While it might fill a hole, Martin Amis won’t be losing any sleep. To wit, “Collaborating with Prince Xizor was about as safe as being trapped in a cave with a hungry Krayt dragon” [Shadows Of The Empire by Steve Perry] – a sentence which pulls off the mindbending literary trick of using a simile where the reader has no idea what it’s referring to.As the momentum for the franchise hit fever pitch with the prequels announcement and the release of the ’97 Special Editions, Star Wars became more than just a blip on the cultural radar. Filmmakers, sitcom writers and comic book artists alike began lacing their work with nods into a nexus of nostalgia and ‘70s hipness (PTA in Boogie Nights), others (Kevin Smith, Simon Pegg) simply because they love it. The ability to catch these references and share them with others is a vital trait of Generation X-wing, becoming an identity and badge of honour for those who get the joke. The residue of all this is that, whether it’s a Darth Vader Tunes commercial, or the multitude of fan films (such as Troops and George Lucas In Love), we’ll take our Star Wars fix any way we can get it.

Even more important than the action figures were the books. In 1991-93, against all the literary odds, a trilogy of Star Wars spin-off novels by Timothy Zahn – Heir To The Empire, Dark Force Rising, The Last Command – topped the New York Times bestsellers list. The books kickstarted a plethora of ‘Expanded Universe’ fiction, which has sated the fanbase in the gaps between movies. While it might fill a hole, Martin Amis won’t be losing any sleep. To wit, “Collaborating with Prince Xizor was about as safe as being trapped in a cave with a hungry Krayt dragon” [Shadows Of The Empire by Steve Perry] – a sentence which pulls off the mindbending literary trick of using a simile where the reader has no idea what it’s referring to.As the momentum for the franchise hit fever pitch with the prequels announcement and the release of the ’97 Special Editions, Star Wars became more than just a blip on the cultural radar. Filmmakers, sitcom writers and comic book artists alike began lacing their work with nods into a nexus of nostalgia and ‘70s hipness (PTA in Boogie Nights), others (Kevin Smith, Simon Pegg) simply because they love it. The ability to catch these references and share them with others is a vital trait of Generation X-wing, becoming an identity and badge of honour for those who get the joke. The residue of all this is that, whether it’s a Darth Vader Tunes commercial, or the multitude of fan films (such as Troops and George Lucas In Love), we’ll take our Star Wars fix any way we can get it.

That the franchise can be served up in so many different forms is a true testament to the age in which it was made. Growing up in a postmodern, post-ironic, Postman Pat era, the Star Wars generation is marked by its ability to embrace high culture and low culture, the cheesy and the heartfelt, in equal proportion. Within moments, Return Of The Jedi veers from old-time serial clunkiness – look out for the camp-as-Christmas Imperial officer who hisses: “You rebel scum!” – to the genuinely moving – Luke battling Darth and his own demons on the Death Star. Star Wars kids are happy to embrace both ends of the spectrum, and it’s this sensibility that allows Star Wars to be stretched the length and breadth of culture without diluting the original.

This all-embracing approach also means it is very difficult to shake your fanbase — witness the passionate reaction this week to the announcement of Episode VII. Just as it filled Luke’s head as smithereens of Death Star fluttered in space, Obi-Wan’s maxim’ “The Force will be with you…always”, reverbs around our own universe. And if Star Wars has taught us anything, it is that you ignore the disembodied voice of a slain septuagenarian hermit at your peril.