There has never been a shoot like it. The technological breakthroughs, the precise detail, the boundless expectation. And a director who has been absent for 20 years. Ian Nathan visits the set of a galaxy far, far away (near Leavesden, Herts.) and charts the full story of the creation of Episode I.

(This story was originally published in issue 122 of Empire Magazine.)

A green gnome with a gnarled face like Walter Matthau spliced with an ageing Mogwai is propped drunkenly on a miniature art-deco throne. The undignified pose – the midriff forward slouch of a ventriloquist’s dummy revealing tufts of salt-coloured hair tenaciously holding ground behind pointy Spock ears – is attributable to the fact that the large rods affixed to pertinent parts of his rubbery body are currently slack. These metallic puppet strings lead back to a clutter of geeky humans, uniformed in blue-jeans and sticky T-shirts and listening intently for the vocal cue to enact a precise waggle of the rod as relayed from a woman sat cross-legged on the floor some feet distant with an open script on her lap. The squat green figure is bathed in an orange light, reflecting hypnotically off the wall, but it is a severe looking black camera that is gathering most attention from the assembled throng.

Despite the fact that a lacky seems to be poking a stick up his arse, there is still something reverential about being in the presence of Yoda. There are movie sets and then there is Star Wars. And for these awestruck moments as the scene is assembled, Empire loses all professional purpose and edges closer to the centre of the movie universe. A kind of religious exaltation, replacing cynical overview. Don’t let anyone ever tell you Star Wars is just a movie.

September 1997, Leavesden Aerodrome, near Watford, Hertfordshire.

Passing from wartime aerodrome use to Rolls-Royce for the construction of aircraft engines, this set of old hangars and offices was converted into a grown-up studio when Bond returned from exile and GoldenEye failed to find room in its spiritual home of Pinewood. Almost inertly peaceful on a warm September afternoon, there is little sense of history being made or, indeed, of a major motion picture being shot, at all. That is, if you discount the sand-coloured buildings sitting anachronistically in the middle of the craggy old runway, It's a pointed marker that this is the home of Star Wars Episode I.

You leave the day the film opens. You just get on a plane. I think we've done everything in our collective imaginations to actually try and create something unique and wonderful, big and large and interesting.

Inside, Empire drifts surprisingly unharassed by the reputed vehement security that surrounds the shoot, travelling the labyrinth of offices that possess that strangely familiar musty odour of a late-70s comprehensive. The production office itself is a sprawl of paper models, diagrams of weirdo creatures and droids, costume designs scribbled over illiterately (leaving the consideration as to which one of the intense scrawls belongs to Mr. Lucas) and, alarmingly, on one crowded shelf there is a file marked "Sofia Coppola".

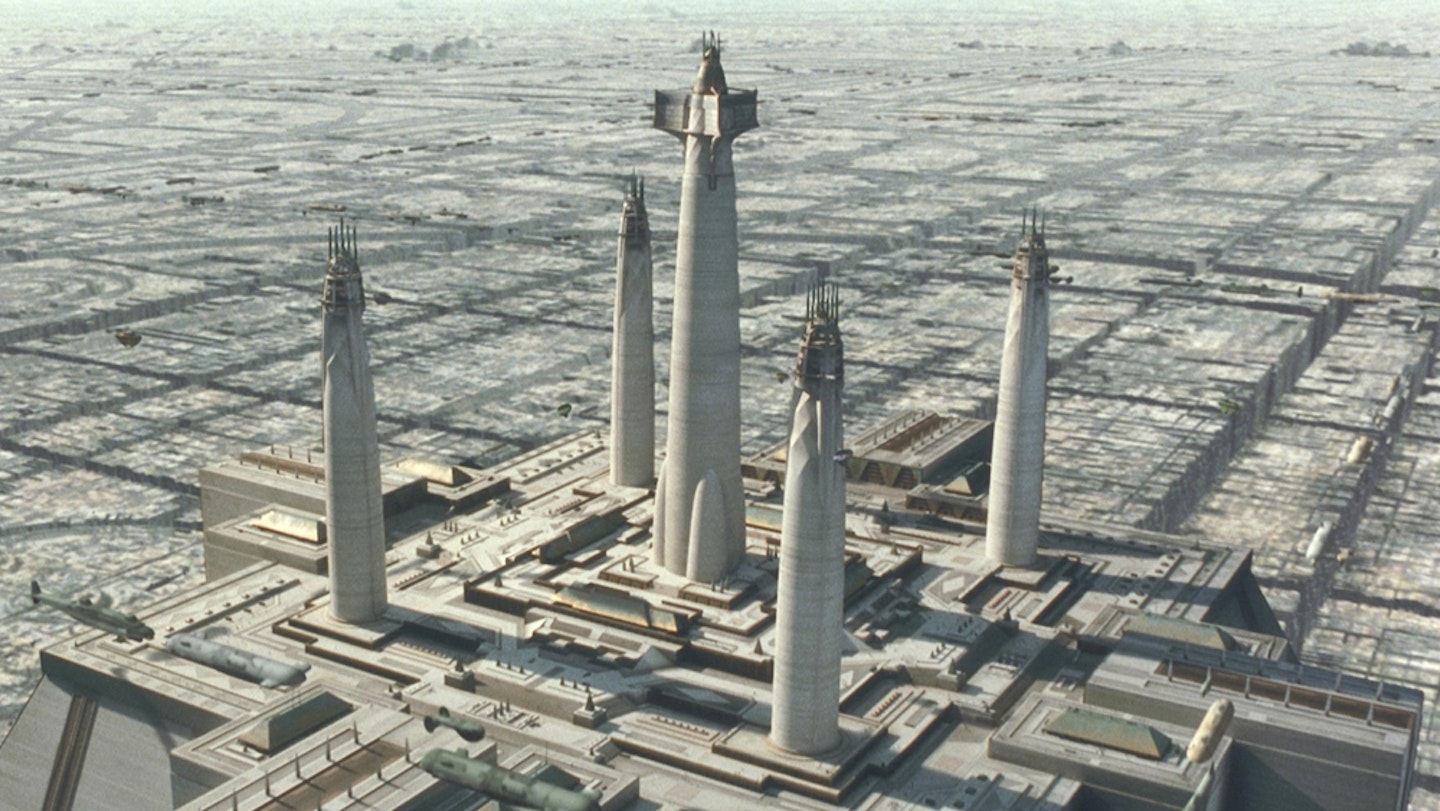

Once embarked on the official tour, led by the perky PR seemingly impervious to the import of what surrounds her, Empire is guided through workshops scented with the smell of freshly brewed tea and the sight of British workman not doing much at all (if this whole reverential thing is lost on the PR, the workers are damned Philistines). Chunks of spacecraft, indefinable robotics and large slabs of grey-painted balsa litter the place. It all seems so very workaday. In one corner stands a battered, full-size Landspeeder. In another, a tank-like craft that possesses no tracks - it later transpires this is an AAT Battle Tank, utilised by the Trade Federation, which hovers. Now, though, the PR isn't letting on, only smiling tolerantly as her journalist reverently strokes the pristine hull of a spacecraft as if some mystical healing property might be transferred. Through another doorway lies a voluminous spacecraft hanger full of curvaceous yellow star fighters - Naboo N-l Starfighters - the background a swathe of blue curtaining, the blank canvas onto which the digital art will be painted.

Empire is joined on its fabulous recce by various brass from LucasArts, Lucas' computer games division, and every time one of them asks the beaming PR the relevance of a location to the mysterious plot, Empire is quietly ushered out of earshot of the reply.

There is no second storey to any of these sets. Upper floors and backgrounds will be supplied by the ILM whizzkids, leaving volumes of background plates to fill in the gaps. A fact that left the tricky situation of the six-foot-four frame of Liam Neeson poking out of the top of some sequences.

"I'd planned to build only up to six feet," laughs producer Rick McCallum as he chats to Empire later. "Just enough to get the actors in shot against actual backgrounds. Then we cast Liam so we had to raise that minimum height. He ruined my budget!"

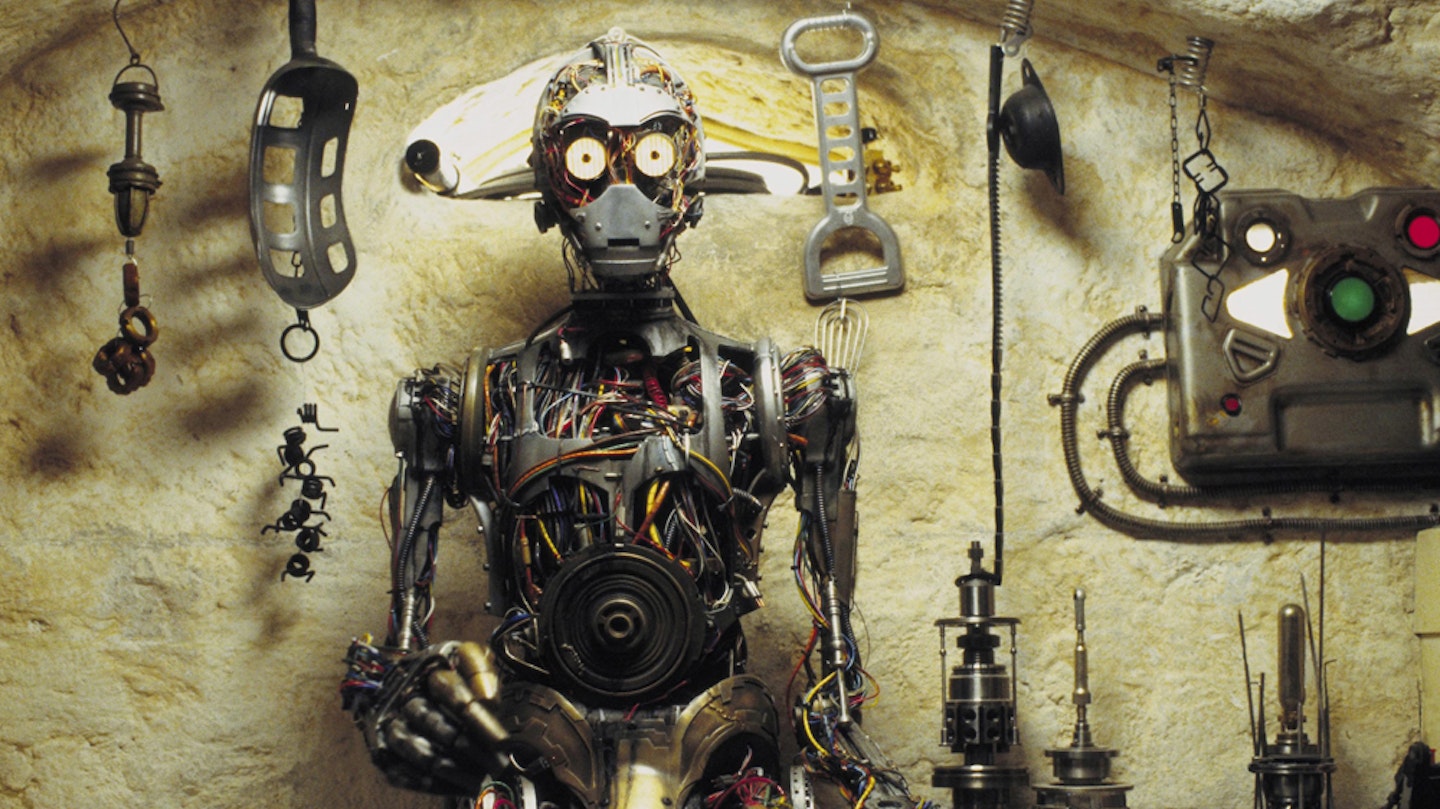

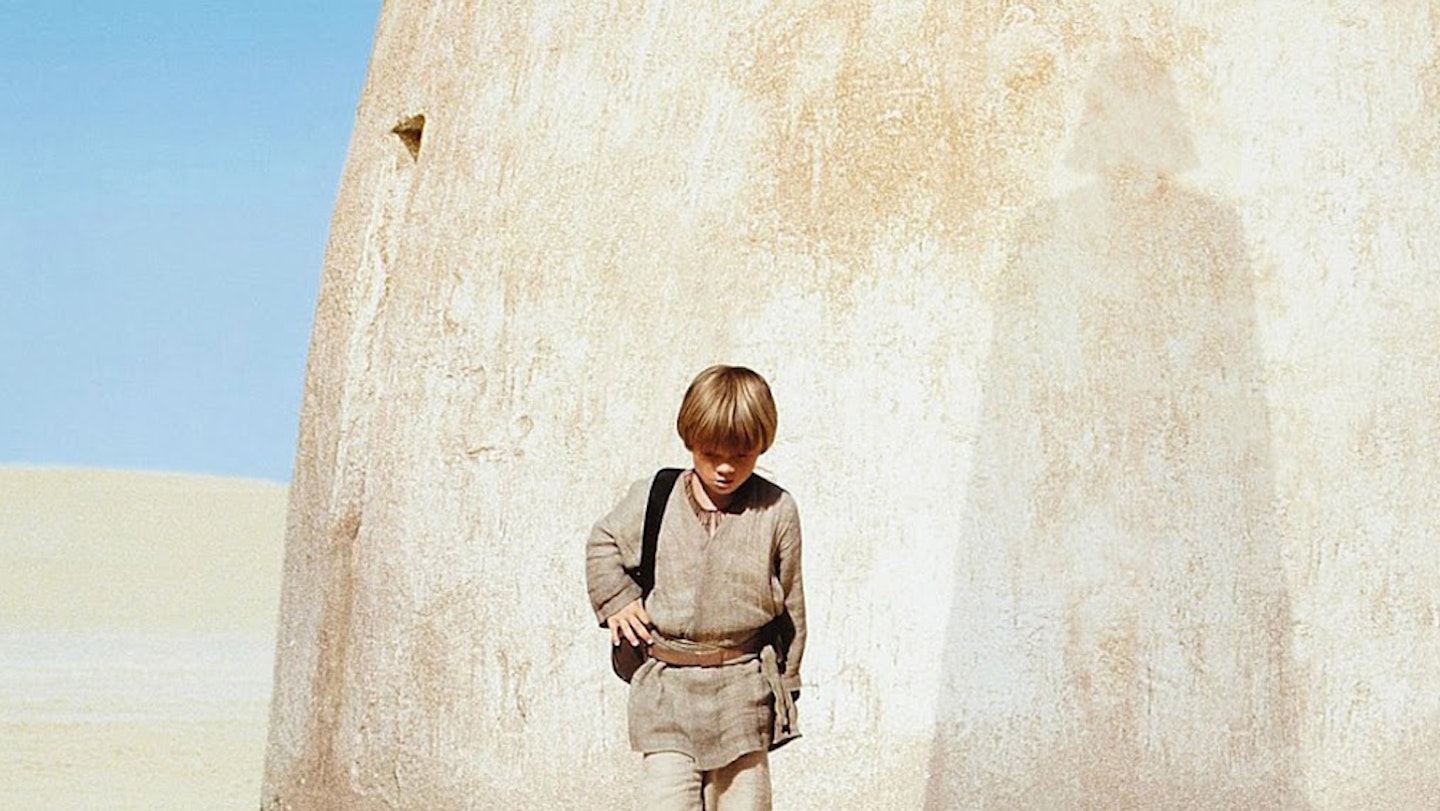

On yet another sound stage sits Anakin's home, the familiar grey mound-like affair of Mos Espa (the grotsville Tatooine slum that is home for the youngster). Upon entering the precision-built hovel, intricate design features mix with the ramshackle old otherworld that Lucas really digs (the new/old aesthetic that made the originals so inspired).

In various other rusty hangars there are vast palace stairs, spacecraft interiors and temple-like constructs - all, on close inspection, disconcertingly held up by some four-by-twos, a few nails and the goodwill of the British grips. Somehow, after incalculable Industrial Light And Magic miracles, all of it will - as you read this - have become the glorious multifarious universe of George Lucas' imagination. And then there is Yoda taking life at the command of the puppeteers.

"Do or do not. There is no try."

Star Wars is being born. Again.

Autumn 1992, ILM, Marin, California.

While Steven Spielberg assembled his masterwork Schindler's List in the cold ruins of Auschwitz by day, he left his Jurassic Park editing to the weary evenings. Some workload. Inevitably he was after someone he could trust to manage most of Jurassic's unprecedented effects editing. Enter best bud George Lucas. The man who invented ILM, the epicentre of computer film technology where those dinosaurs were currently finding their legs. And as Lucas watched a living, breathing T. Rex appear from a bag of pixels, he knew the time had come. The technology was ready to fulfil his storytelling ideals. Digital was making waves throughout the industry from the liquid metal morphing of Terminator 2 to Goldie Hawn playing her scenes minus a midriff in Death Becomes Her. It was time to go back to Star Wars.

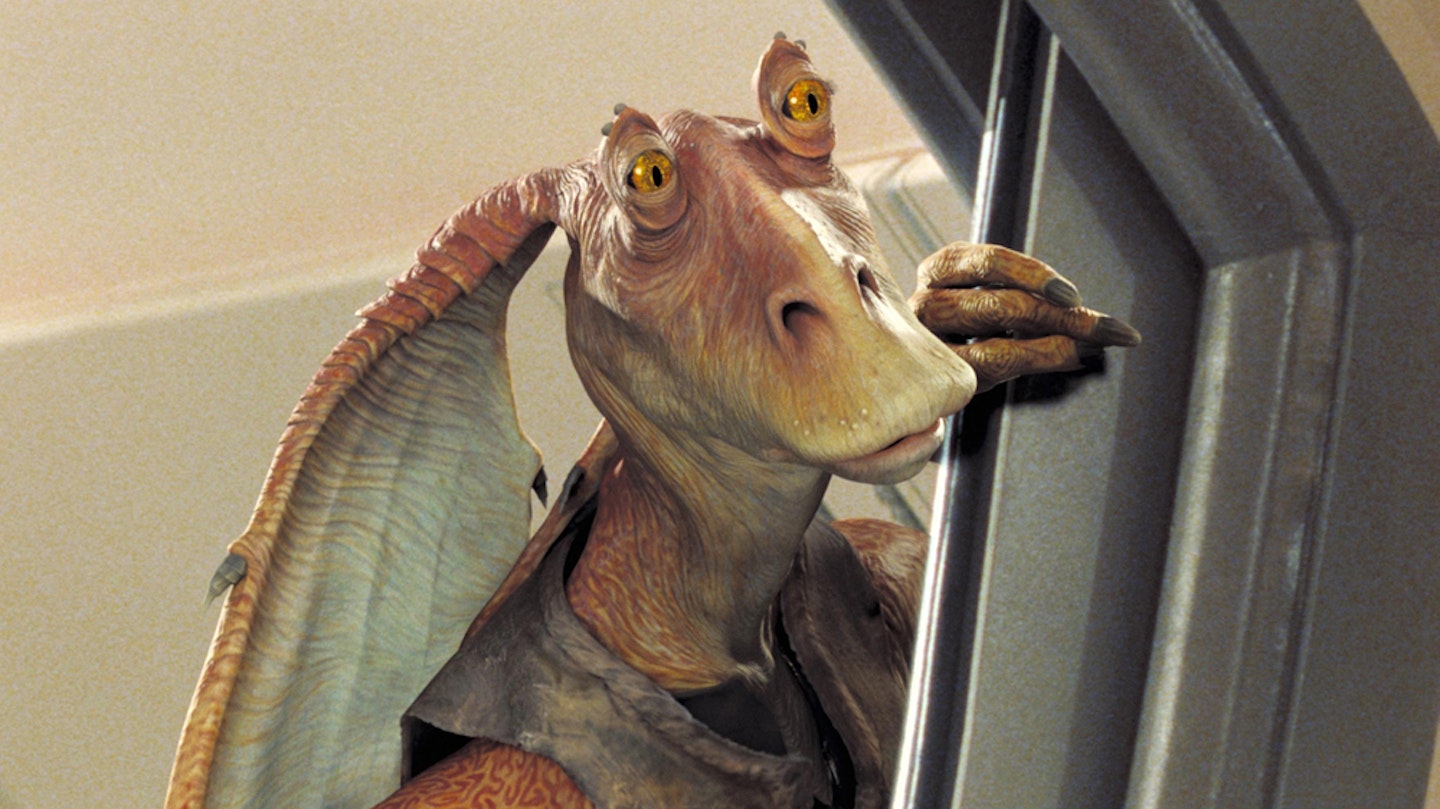

"Throughout the Star Wars films, I was struggling with such questions as, 'How do I create a Jabba The Hutt?'," said Lucas. "'How do I create a Yoda, who's only a foot-and-a-half high, and have him play a scene?' I've finally reached a point where I can move such characters freely on a set, and I can get better, more dramatic performances out of them."

First things first, though. Spruce up the original three movies, send them out to the cinemas again and see if modern audiences are as receptive as their predecessors. Testing digital technology's limitations in the process.

Producer Rick McCallum, 47, first met George Lucas while working on the Dennis Potter movie Dreamchild in 1985. Lucas had popped over to visit the set, while he was also at Elstree - proving that there are some movies that can never be revisited with Return To Oz (on which he worked in an advisory role).

"I could tell that he was amazed that there were only 18 of us making a movie," recalls McCallum. "On his set, there were about 250 and he likes things small. They're big movies but he likes to make them in a small way. It's ironic that the person who made THX and American Graffiti is now known as one of the biggest filmmakers. George's passion is for much smaller, intimate, films - in terms of the process."

A mutual producing friend, Robert Watts, introduced them again in 1990 when Lucas was setting up the Young Indiana Jones TV series. They got along and Lucas hired him for the job.

The series' success, not only in financial terms but in the way it managed to produce a television series with the production values of a movie - and progressed the use of computers to include effects, many of which were essentially invisible - set in motion McCallum's role as producer of the re-releases.

"The thing with George is, he never says, 'Hey, you wanna do Star Wars?' One day he just says, 'Oh we'd better start working on Star Wars.' So he doesn't ask you, he just assumes that you want to carry on."

January 1997, USA.

With a minimal investment of $15 million, the retinkered trio of Special Editions are re-released featuring some whizz-bang digital improvements, new scenes and a delicious pointer of the shape of things to come. Amid some typical Hollywood nay-saying, the world immediately went Star Wars bonkers again, the trilogy picking up another $475 million. Hello mama. If there was any doubt about the enduring power of this fantastical universe's pan-generational appeal, it was instantly drowned under a tidal wave of anticipation for Lucas' major return.

November 1994, Skywalker Ranch, Marin, California.

George Lucas, 50 years old, sits-down at his desk adorned with toy models of Star Wars characters. Grabbing a handful of No.2 Ticonderoga pencils he opens up his weathered ring binder (the very same one he used on American Graffiti) and begins to write.

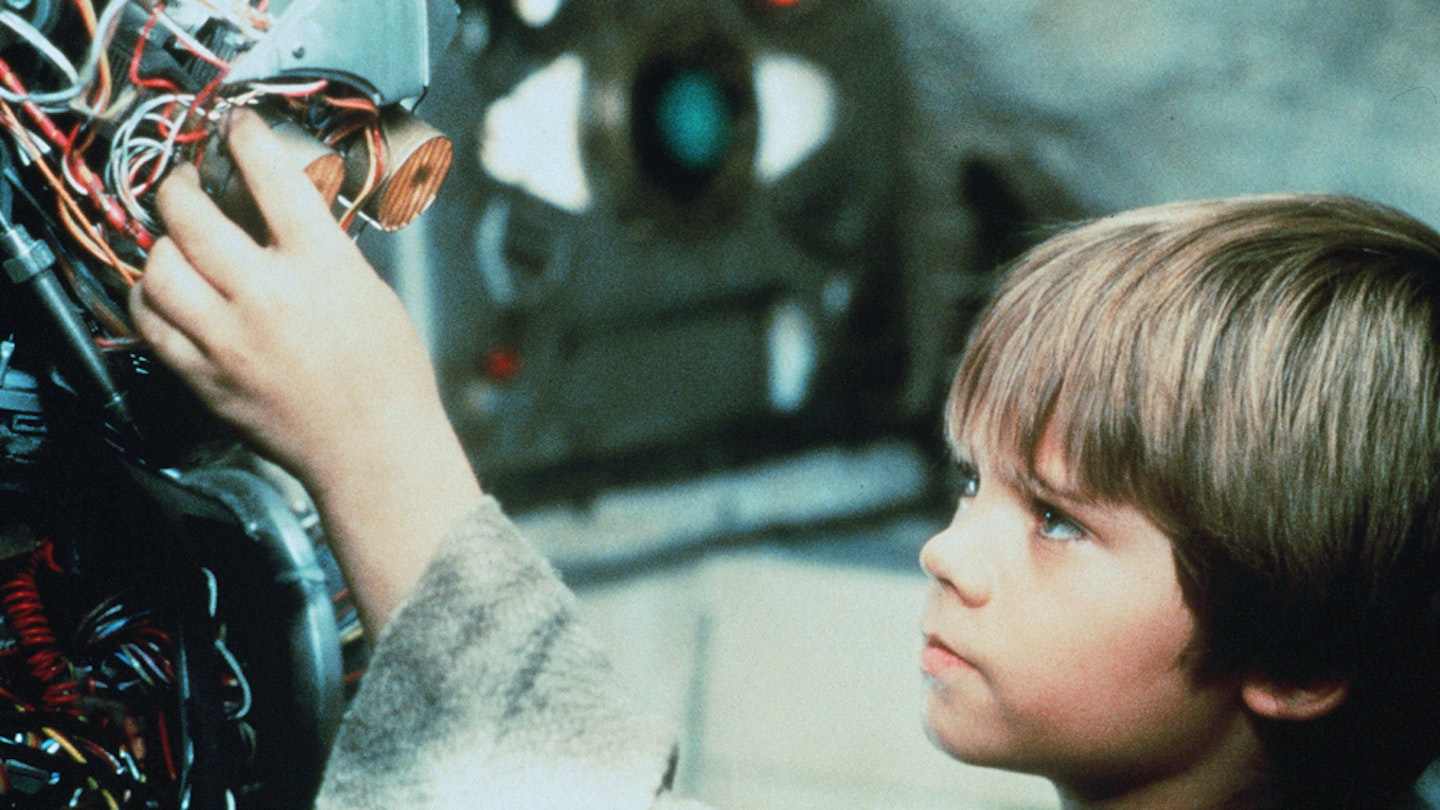

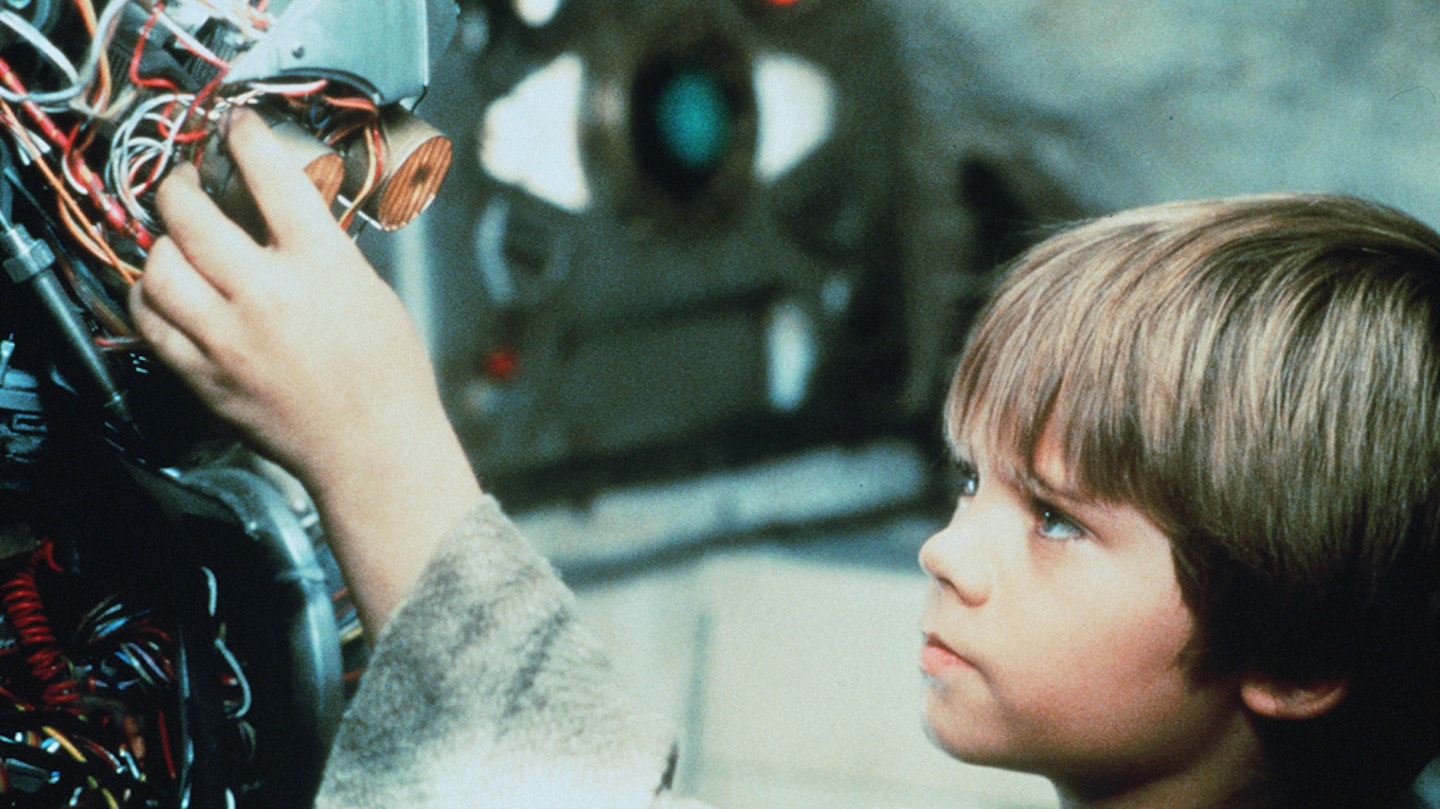

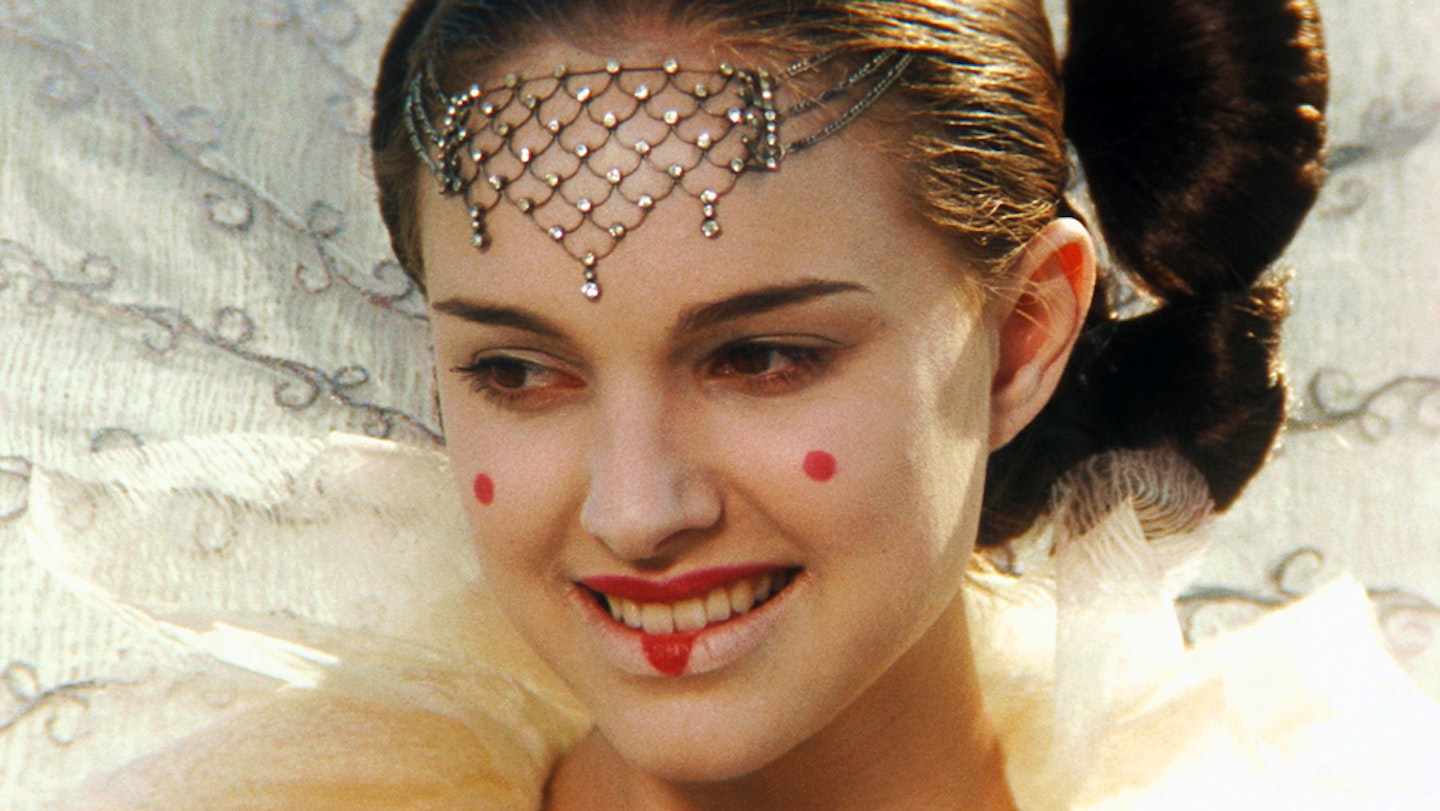

Returning to the formative story which he conjured up back in the early 70s, then sloughed down to make the middle trilogy we all know and love, he was now required to form the details of Anakin Skywalker's childhood, the early lives of Obi-Wan Kenobi and Luke and Leia's mother Queen Amidala and, as it surprisingly emerged, the comedy droids R2-D2 and C-3PO. It would be a long, arduous process. The writing part of a movie he doesn't enjoy ("To me it's like doing a term paper"). But so it began...

An even longer time ago in a galaxy far, far away.

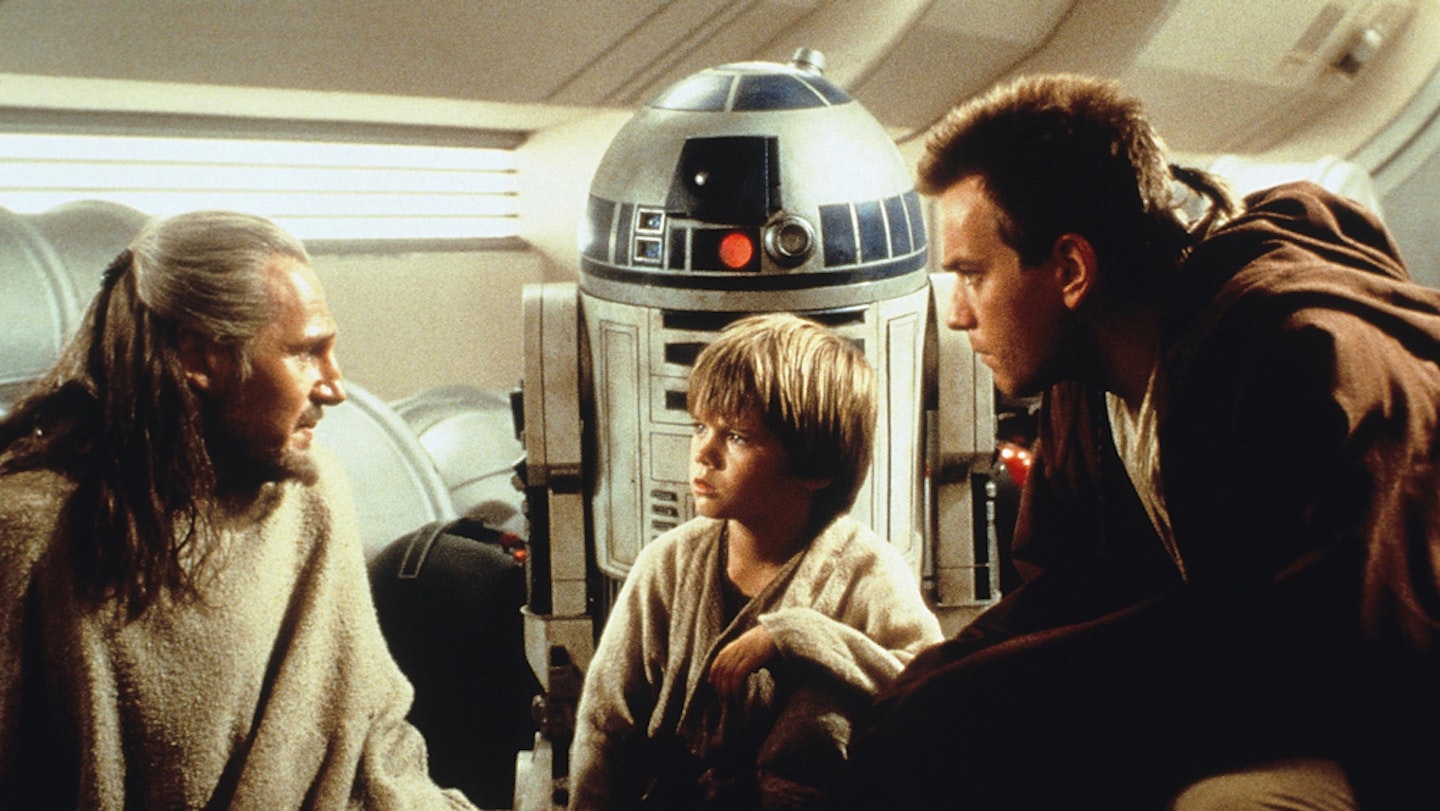

Set about 30 years before the events of A New Hope (Episode IV, keep up at the back) Lucas' prequel concerns the origins of Darth Vader, at that time, a boy named Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd). Naturally there is a whole lot more going on. For starters, a venerable Jedi Qui-Gon Jinn (eventually to be played by Liam Neeson) and his rebellious apprentice Obi-Wan (Ewan McGregor) are playing peacemakers between the titchy indie planet of Naboo - led by Queen Amidala (Natalie Portman) - and the bully-boy Trade Federation, who are about to get medieval...

They tried out around 7,000 young boys for the role of Anakin.

The cool Jedi whisk away the young queen, crash land on desert planet Tatooine, happen upon a little slave boy (Anakin) strong in the ways of The Force and set the rascal upon a historic path toward Jedi Knighthood and an eventual fall from grace. Oh, and not to forget the bad guys (Dark Lords Of The Sith) in the forms of evil master Darth Sidious and his henchman Darth Maul (Ray Park) setting about wiping out the Jedi and manipulating all available parties for their own benefit. Got it? Fine we'll continue...

July 1995. Skywalker Ranch.

While Lucas called Doug Chiang, director of concept design, to commence the process of creating the visual look of Episode I, McCallum hired Robin Gurland as casting director to flesh out their cast.

Gurland would begin a quest similar in scope to that of her fictional quarry, covering seven different countries over two years. The only remit given in terms of eligibility was whether "they were right for the role". There were immediate challenges: a young actor who harkened to a youthful Alec Guinness for Obi-Wan; a boy who would have the ability to suggest a wavering morality; a venerable Jedi, canny enough to sense the future. As Gurland came up with candidates they were ushered into informal meetings with Lucas and McCallum where they chatted about everything from politics to family, everything apart from Star Wars. At the close of Neeson's chat, when the subject had rarely ventured from family matters, Neeson turned to the director and said, "For what it's worth, I would love to be in Star Wars."

"Most of the first year of casting was primarily the kid," explains McCallum on the tortuous process that faced them. "Because we didn't know where we were going to go. Robin went everywhere, she went to France, Germany, England, and all over the States.

“We didn’t know where the kid was going to be, but we knew we were going to have to look at seven-year-olds and track them until they were nine.”

By all accounts they tried out around 7,000 young boys for the role of Anakin, before “one of those miracles happened” and Jake Lloyd (who was a veteran of two movies Unhook The Stars and Jingle All The Way) was recognised as the chosen one.

Then there was the choice of Ewan McGregor as Obi-Wan.

“We had a reference point, Alec Guinness, and Robin said, ‘Look, there’s this fantastic guy called Ewan McGregor’. I knew Ewan’s wife (Eve Mavrakis) – she used to be a production desinger on Young Indy and I loved her to death – but I could only think of him in Shallow Grave and Trainspotting. So I said, 'You know, I don't know if that's going to work, that's too class-oriented. You got to remember that unfortunately in England there is a class system'."

However, Gurland convinced McCallum to watch Emma and surprisingly (McGregor deems it his acting nadir) he in turn decided to give the actor a chance.

"Robin got all of Guinness' early films and she scanned them in and then she took Ewan and placed him right next to him and they were very similar looking: you could see there was this huge connection between them. Then we met him, George and I, and that was it."

Samuel L Jackson's brief but noted cameo as Jedi councillor Mace Windu happened simply by request. He was on a UK talkshow when the question was posed: 'What would be your fantasy if you could be in any movie?' And he replied, with all due Jackson-sized gusto, 'Gee, I'd love to be in Star Wars.'

"So we called his bluff," laughs McCallum, "and - boom! - it just happened."

August 11,1997, outside Tozeur, Tunisia.

Call it portent, call it the work of The Force, but there was something mighty weird going on on this day. Namely rain. Shitloads. Twenty-one years before in exactly the same location when shooting the early stages of Star Wars, the first rains for five years had pelted Lucas' set, throwing the fragging schedule into complete disarray, compounding the organisational nightmare of shooting a film in the barren deserts of Tunisia. Two decades on, just two days into the shoot, as the cast and crew fought its way through the will-sapping 120 degree temperatures, a storm crept into the hitherto empty skies and struck with the ferocious power of a Star Destroyer, levelling the set in one fell swoop. Ferocious winds swept all before them, crushing the Mos Espa sets, picking up the huge 3,5OOlb aircraft engines that made up the Podracers (5OOmph junk hybrid craft raced for money across the desert) and hurling them across the set ("It was like watching Twister," says McCallum). Costumes and hairpieces were destroyed - they couldn't find Neeson's 'tache for love or money - one crew tent reputedly landed in Kenya.

But such is the supreme command of a George Lucas shoot in 1997 that the production was back on its feet within days. The Tunisian army, nearby for manoeuvres (which most likely involved taking a sneaky peek at a new movie being shot), were roped in to help, the set builders were flown back at a moment's notice. Lucas was in command now, and not a day was lost from the Tunisian schedule. Studio moguls or extreme elements - now there is no power that can stand in the way of Lucas and his baby.

September 1997, Leavesden.

Rick McCallum emerges from behind a bank of files, his face adopting the confident smile of the man who is producing Star Wars Episode I. Pulling up a chair at a small meeting table, he proves an amenable unhurried talker (while secrecy still enshrouds the plot), cagey on detail but open about the whys and wherefores of the actual production.

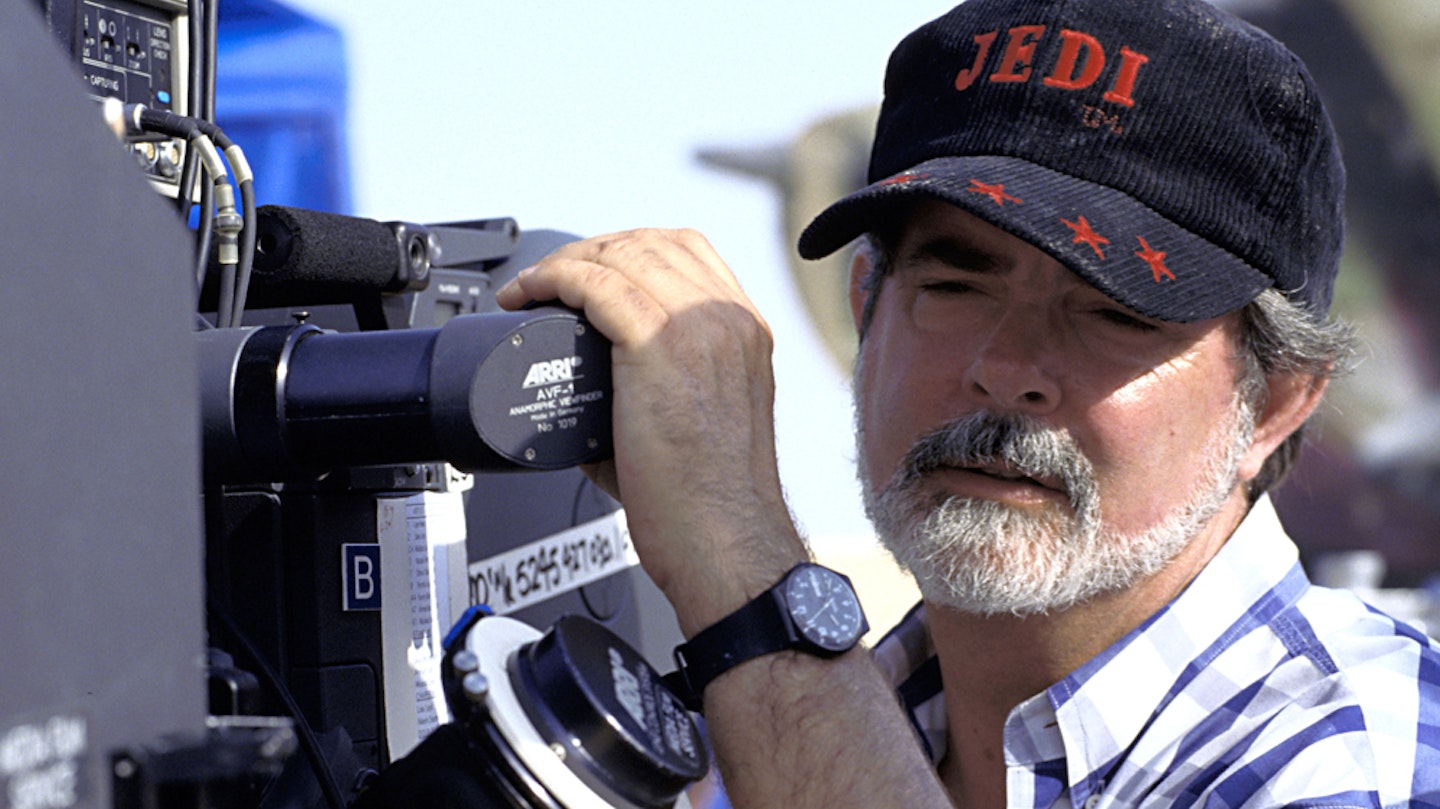

The 65-day shoot that would take in the studio facilities of Leavesden, Caserta in Italy and the desert canyons of Tozeur, had begun its formidable schedule on June 26 (the same day Spielberg began Saving Private Ryan). Despite, or perhaps because of, the vast numbers of computer effects to be mantled later on, this was to be a gruelling shoot. But not in terms of personality. Lucas runs his ship with an autocratic will that behoves the fact that no one can actually argue with the one mind that has conjured up all this mystical grist. There were up to 36 set-ups a day ("George doesn't have a trailer," notes McCallum on the fevered approach his boss takes. "Half the time he doesn't even have a chair") - most movies manage about seven.

We really started the movie on blind faith.

"We don't have the usual dramas that exist on big films," McCallum says of the difficulties the shoot has faced. "After the Young Indy experience there was nothing that we hadn't seen or done. It was a relatively easy film...The cast were wonderful, they were fantastic, the effects were very complicated. That was the most difficult aspect; trying to combine the forces of ILM and the production because we only really shot on the floor. We have two huge completely digital sequences - the Podrace and the end battle."

The technical specifications of the movie are staggering: 2,500 set-ups, 2,100 shots of which 95 per cent include some digital element. That's a lot. Virtually 2,000 of that total were effects shots (Titanic had about 550) and in all the CG element was three times greater than Jim Cameron's previous record holder. As much tradition and nostalgia that surrounds the new film, this has been a revolution in moviemaking terms.

"It wasn't like a normal film," continues McCallum, "where you shoot and then you hand over the film to ILM. We were very collaborative in the whole process. Even though it is George's company, it is a separate company. The biggest problem was that at the outset we didn't have the technology to actually achieve any of this, so we really started the movie on blind faith."

For the cast this was a totally new moviemaking experience. A world of acting with nothing but blue screens, metal batons (for lightsabers) and blokes with wobbly rubber heads who would later be replaced with the hi-tech digital equivalent.

"I don't think Ewan had ever seen a blue screen in his life," says McCallum, "and Liam certainly hadn't, nor Natalie. With Jar Jar (an entirely digital character in the movie) we would film the actor playing the voice, a really wonderful boy named Ahmed Best, and all his mannerisms. He would be there in a costume looking like Jar Jar, this head sticking out with these ears and eyes and everything else. We'd actually shoot the scene with him so the animators would have a colour and timing reference, and also so the actors would have their eye-lines."

None of the actors had any real idea what this movie would eventually be like to work on. For McGregor, at least, it proved to be an exacting process, slow and, in acting terms, tedious.

"A lot of it will be done over and over again," the superstar Scot later confessed. "And you're doing it for a very long time as well. And it's studio based so you're always in whatever environment you are in. I mean you're not in Star Wars, you're not in space, you're sitting on a spaceship with a camera stuck in your face and all these people around you. You just want to be doing the real thing."

"It's just a tool like sound or colour," is the refined opinion of George Lucas talking later in New York. "It has absolutely nothing to do with the story except you can tell the story better and much more easily than you could in the past. More and more filmmakers can realise their vision and not be stifled in using their imaginations to tell stories."

For McCallum, as producer, there was a change of dynamic in terms of his role. With no studio to be kept at bay - 20th Century Fox are only the distributor (and take only ten per cent of the grosses), Lucasfilm stumped up the entire $115 million budget themselves - the crux of his job lay in making Lucas' path as smooth as possible.

"When you work in this situation, unlike Indy or any other project that George and I have worked on, it's basically his thing. He's created the universe, he understands these characters, you have to build every single element of this film. There's no prop or wardrobe shop that you can go to. The writer part of him can be very difficult and slow, but the director part of him gets the writer to make compromises and the director part of him understands the process of making a film so well that he helps in any way to make the picture better. He's just very easy and very laid-back and very supportive to everybody. The great thing about working with George is that at the end of the day we can't blame anybody. You know, we can't go and say, 'Well, the studio forced us to and we had to make cuts to the script and we had to do this.' If it doesn't work, we're the idiots, we can't blame anybody. And that is terrifying and very liberating at the same time."

November 17, 1998, Los Angeles.

The Star Wars machine, after aeons of quiet time, began to gear up - a trailer, a poster, flits and sparks of story, began to emerge.

The first poster is certainly subtle. Anakin posed thoughtfully in the foreground, Tatooine's bleak landscape behind him to the horizon, empty apart from the curve of a dwelling. The spin is the boy's shadow. It is not his own - at least not in this time zone - it is Vader's. His destiny. His doom. Cool!

Then the trailer. Sorry, the teaser trailer. And boy, what a tease! Touching base with all those Star Wars motifs of yore but offering the forefront of film technology. And a double-frigging-lightsaber being swung about by greasepainted bad guy Maul!

It inspires the kind of frenzy normally reserved for Royal Weddings, World Cups and the opening day of the Harrods sale. Desperate folks queue for such duds as The Siege and Meet Joe Black simply to see the trailer, then get up and leave before the main movie begins. There are reports from New York of fans taking a day off work to dash from cinema to cinema to watch it over and over again.

The campaign to launch Star Wars Episode I to the public is a curious thing. Why bother at all? This has "sure thing" written into its very fabric. Fans don't just want to see it, they crave it. Clans of devotees on the 'net wrestle with the minutiae of the info they are fed by the Lucas machine in tiny globules. A religion has grown up where leaked info and pictures is valiantly assembled into some impossible morsel for the desperate. And there, by this time, are a hell of a lot of the desperate.

In the geek heartland of the internet, Episode I fever hits pandemic proportions. Sites arise like some nomadic gathering in cyber space to debate, discuss and gather information with craven delight. Half of it, frankly, bollocks.

"That's what the internet does, it's weird," says McCallum, considering both its vastness and its follies. "Somebody came up with the fact that the name of the movie was going to be The Balance Of The Force. Total bullshit. People making it up. That's why I am amused by the internet, I find it extraordinary in terms of where culture and society are going, that you can have somebody sitting at a computer at night saying, 'You know, I think George should call it The Balance Of The Force', then put it out there so the rumour will spread. That rumour was picked up in London by the Times and then all the newspapers picked it up. And no one ever called us. It was bullshit. It was as ludicrous as Charlton Heston playing Yoda."

What, pray tell, was the most ludicrous rumour put about?

"My favourite was that the movie was 40 per cent out of focus," McCallum pulls back, his arms out stretched in remonstration. "That was a really good one. The premise behind it was we shot for 18 months and we didn't look at the film. Eighteen months went by before any of us looked at the movie? Our camera company, the labs, everybody was freaked out... But, you know, it had power."

There was, though, a genuine copy of the script out there, allowing small, but correct pieces of information to be divulged.

"Luckily we have who got it," he says darkly. By April 1999, the truest of the true would start a month-long queue at LA cinemas, broadcasting their endeavours live on the 'net. It was unprecedented. It was ludicrous. It looked like real fun.

"I think a lot of it is not so much mania," says Lucas, "as it is people wanting to have a good time. We live in very cynical, mean-spirited times, a lot of people just want to enjoy themselves and this I think is a good excuse for that. Once in a while you need to have that or you're just going to break."

But there was another, unwritten, agenda. An unforeseen iceberg floating into view while Lucas and crew journeyed their own smooth but unbendable voyage of The Phantom Menace - Titanic. The telling of the ship story with a couple of pretty kids that would carve box office receipts like nothing before it. After it, the question of the Wars becoming the champ of monetary return - as it did so long ago - became a toughy. Could it better the $1.5 billion (excluding video revenue)? Could it? Those involved immediately took the ethical high ground.

We live in very cynical, mean-spirited times, a lot of people just want to enjoy themselves.

"I think it's fantastic," chirps McCallum. "I mean, it's fantastic because it really dramatises and illuminates the basic idea that, if you tap into something...It's so big now, it's not about the money, it's about the people. Over 500 million people saw that movie. That is phenomenal. The success of Titanic showed that there was an even bigger audience than anyone ever imagined."

By January 1999, buzz had grown to hype, with the hype hovering over sensationalism, signalling a passage into outright frenzy coming this way soon. Lucas, though, drizzled on our parades, shocking the adoring fandom by hinting heavily that Episodes VII, VIII and IX were not, currently, on the agenda. Although, it has to be said, there was a degree of ambiguity in his statements.

"That's not really part of the plan," he claimed, breaking millions of Wars fans hearts. "I never had a story for the sequels for the later ones. When you see it in six parts, you'll understand. It really ends in Episode VI."

And he was adamant that no one else would be handed on the galactic baton.

"It's my thing," he added, emphatically.

March 1999, the offices of 20th Century Fox, London.

McCallum is back in town for more organisation and a chance to meet up with Empire again. Sealed in a screening theatre, Empire is witness to a minor discourse that is, well, just so Hollywood. McCallum feels the need for a cigarette and lights up, whereupon a lowly jobsworth walks through the screening room, not only disturbing the flow of the interview but having the impertinence to chastise the producer of the most important film release of the last 20 years for smoking in a no smoking area. McCallum pauses, irritated, and turns to the idiot.

"So go get security," he challenges icily.

The idiot exits scene left and Empire returns to the matter in hand. Has it been tough for McCallum to be the public voice for the movie? After all, Lucas as a spokesman is hardly verbose.

"He would rather let the film speak for itself," says the producer, with nary a hint that his composure may have been ruffled. "It's not a burden. I know there's a real hunger but that's part of the fun of it."

How, though, does the producer manage the extraordinary expectations landed on this movie? McCallum sighs.

"You leave the day the film opens. You just get on a plane. I think we've done everything in our collective imaginations to actually try and create something unique and wonderful, big and large and interesting...It doesn't bug me, the expectation. I mean, I never really get fucked up about it."

May 19, cinemas across the USA.

Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace opens. The maniacal fans who have queued for tickets finally squeeze their way to their seats, settle down with popcorn and soda, and cheer profusely as that inimitable John Williams score begins and the title crawl begins: "A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away .. ."

The wait is over. And when it's over, they leave the auditorium, discussing it in avid detail, and immediately join the back of the queue to see it again. This is not a movie. This is Star Wars.

Visit Empire's celebration of the Skywalker Saga for even more Star Wars content.