This article was first published in Empire Magazine Issue #156 (June 2002).

In the '70s, Harrison Ford spent a lot of time in London. First there was Star Wars, then there was Force 10 From Navarone, then The Empire Strikes Back… He was becoming homesick, and when Ridley Scott first offered him the lead in Blade Runner Ford declined because the shoot, as it was planned at that time, would have brought him, yet again, to London. It's worth mentioning this because, unusually for a Hollywood star, Ford has a firm grasp of the English sense of humour. He has a reputation for being terse and combative in interviews, but, really, this is a man who simply doesn't suffer fools gladly. He's more like a headmaster, affecting a professional detachment while actually daring you to challenge him on an intellectual level. As he told one especially knock-kneed interviewer, "I'm not arguing with you - I just need some definition."

In real life, as on screen, Ford communicates with the minimum of expression, by arching an eyebrow, breaking into a grin or speaking carefully with the emphasis on certain words. The results are impressive, and his time in London must surely have stoked his innate capacity for dry wit to the extent that he now speaks almost fluent irony. And Ford knows a thing or two about irony. Despite being one of the biggest movie stars in Hollywood, he was actually rejected by the studio system in the '60s, as it floundered to keep up with the flourishing independent sector. He was told that he didn't have star quality, and one producer reminded him that even when Tony Curtis was a bit-part actor playing a waiter, he still looked like a movie star. "Shouldn't he have looked like a waiter?" asked Ford.

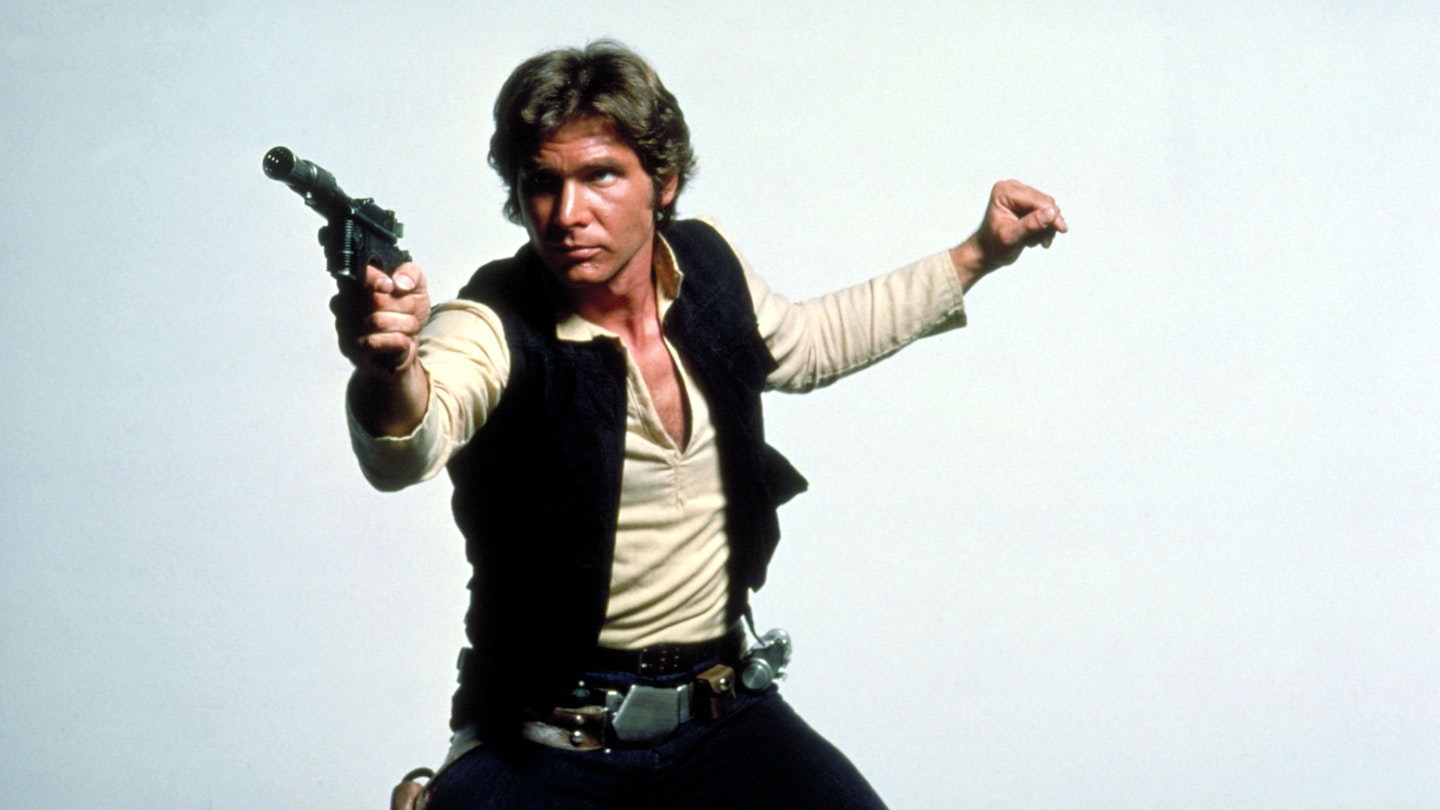

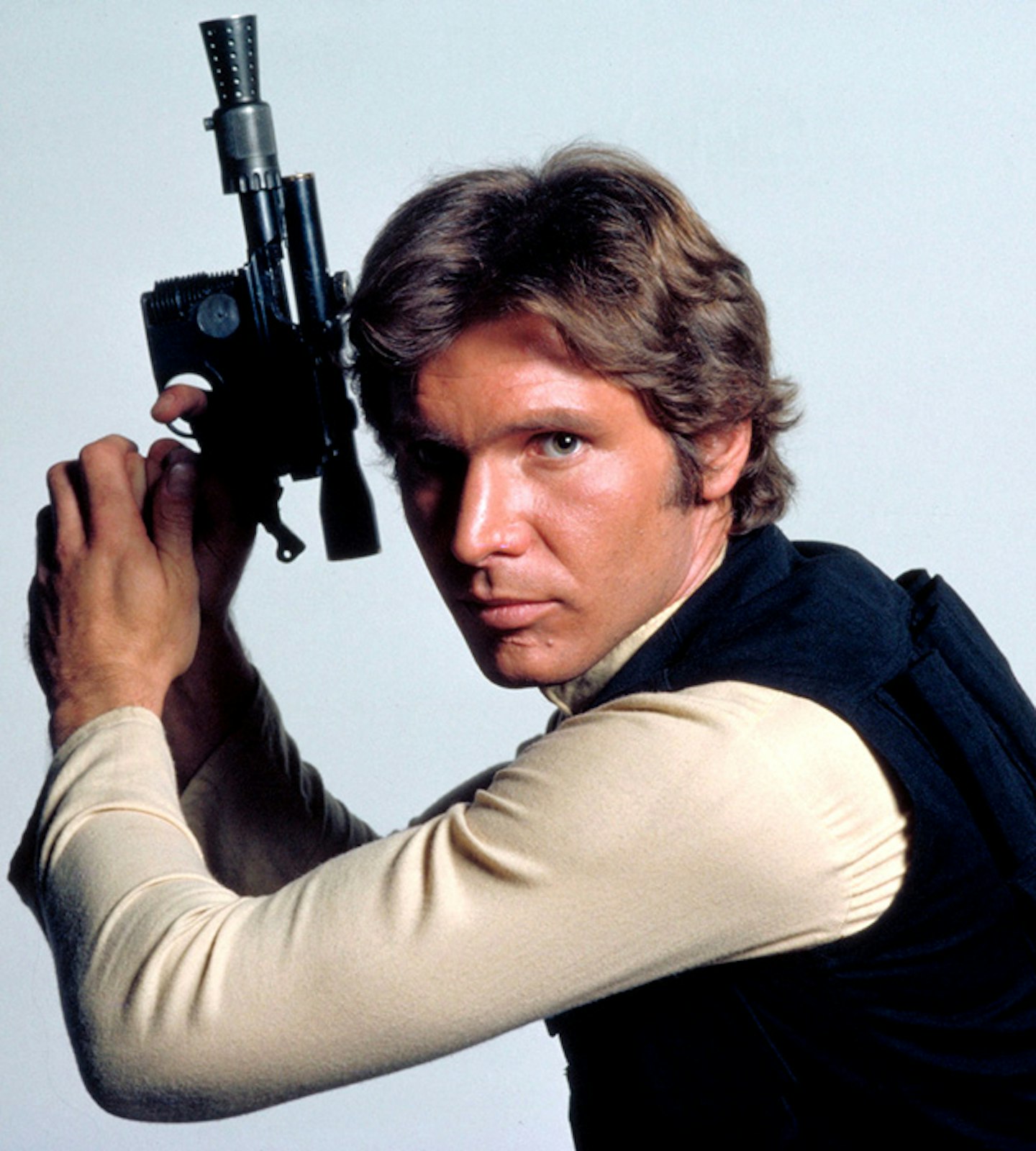

His attitude made him some high-level enemies, but Ford didn't much care for their friendship anyway and opted out of the business altogether for a while, acting as a carpenter to showbusiness stars like Latin musician Sergio Mendes, for whom he built a home studio. And it was while Ford was banging away with his hammer on a repair job, legend has it, that he was reintroduced to George Lucas, then scouting for cheap talent for his 1976 sci-fi production, Star Wars, a minor genre film that 20th Century Fox greenlit through gritted teeth. Ford was paid $2,000 a week in wages and expenses - and that's all. He admits that the amount didn't exactly allow him to live in luxury but, ever the pragmatist, he's quick to point out that the film was a risk for Lucas and that he had a tight budget. "I didn't feel particularly taken advantage of at that point," says Ford.

It would be easy to pinpoint this as the start of Ford's enduring reign as America's box office king, but if that were the case, then Mark Hamill would be up there with him too. Ford's star didn't actually rise until the first Indiana Jones movie in 1981, which put him centre-stage and established the hallmarks of a classic Ford performance. Although firmly based in the early Saturday matinee serials of the '40s and '50s, Jones was a new kind of hero, an action man whose deadly wit and gruff charm catered to all ages and both sexes. Ford himself put his finger on it when he quipped, "I'm a complete coward and a powder-puff when it comes to sport, but I can act fearless."

I'm a complete coward, but I can _act_ fearless.

From this starting point, Ford has navigated a deceptively treacherous course through the last 20 years of filmmaking. He has endured where even the musclebound likes of Stallone and Schwarzenegger have flagged, keeping a close eye on what will and will not work for him. He has been criticised for not taking risks, but Ford knows that if that risk fails, his career goes with it. "You do have to preserve your commercial viability," he once told The Hollywood Reporter, and although this may sound cynical, it actually makes perfect sense. Film is an expensive medium, and Ford, unlike many of his peers, likes to protect his producers' investment. It's also a collaborative medium, and anyone who has ever worked on a set with Ford will tell you how thoughtful, helpful and open he is to the whole team process.

Is there any tradition of acting in your family? What inspired you to start?

My father was in advertising in Chicago. He'd been a radio actor at one point in his career, and I have a grandfather who was a vaudevillian. I was studying English and Philosophy at college and I got thrown out for failing all my courses in my senior year. I was getting married that summer (to first wife Mary Marquardt), and I didn't know what to do, so I decided to be an actor. I had no idea how to go about it, but I knew that, to be an actor, you had to go either to New York or Los Angeles, so that part was easy. I got married and we drove to California. I was very lucky. Within six months I was under contract.

After signing with Columbia, what was your experience with the studio system?

I did a year and a half and got kicked out on my ass for being too difficult. I was very unhappy with the process they were engaged in, which was to recreate stars the way it had been done in the '50s. They sent me to get my hair pompadoured, like Elvis Presley - all that shit - for $150 a week. So I decided to become a carpenter, as an alternative to taking roles I didn't want to take. I was trying to make the transition from episodic television to features, because I'd been playing the same stock part time after time. I played the same guy on ('60s TV show) The FBI three times. I realised I was going to wear out my face doing episodic TV.

But you almost went too far the other way.

Right. As a matter of fact, that was a bit of a problem for me at the beginning of my career - the problem of identification. In The Conversation I played a character who was gay, so nobody recognised me from American Graffiti. When I did Apocalypse Now, after Star Wars, I played an intelligence officer of the American army. George Lucas saw the footage I had done and didn't recognise me until halfway through the scene.

When did you realise your career was really on track?

American Graffiti was the first movie where the director let me have any input. It was the first time anyone ever listened to me. George thought my character should have a crew cut, but I wasn't happy with that idea. I'd always had pretty long hair back then - in college, particularly - so I told George my character should wear a cowboy hat. George thought about it and he remembered a bunch of guys from Modesto, California, who cruised around, like my character, and wore cowboy hats, so it turned out that it actually fit the movie.

I was one of the few people who thought Star Wars was going to work, and I hadn't even seen any special effects.

It's safe to say you weren't exactly an overnight success.

That's true. I was 35 when I first hit with Star Wars. I had some degree of maturity and some degree of experience, yet physically I still looked young. That had been an impediment early on in my career, but then it turned out to be an advantage.

How do you feel about that film now?

The basic feeling is that it was a long time ago and far, far away.

Did you think it would be a success while you were making it?

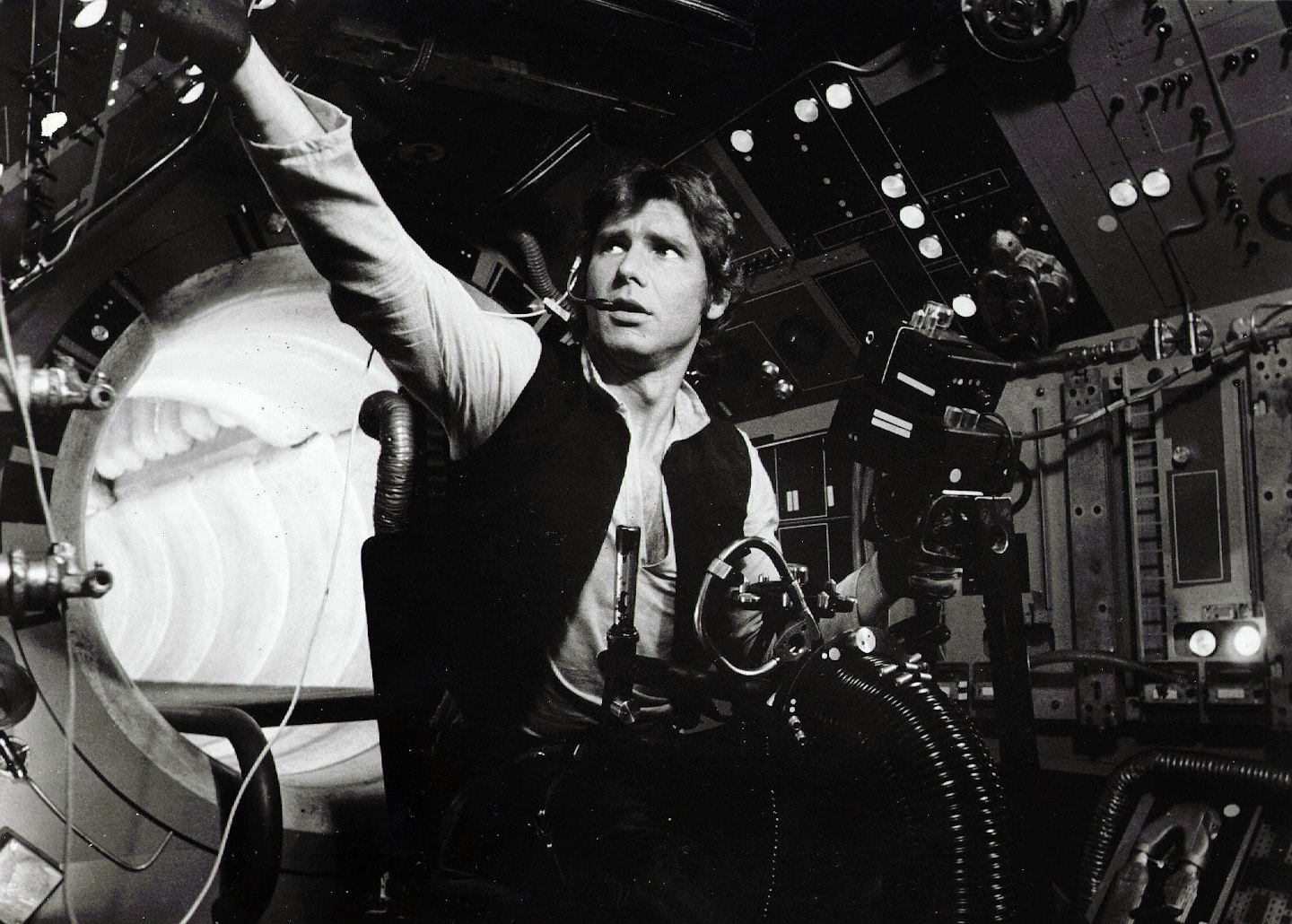

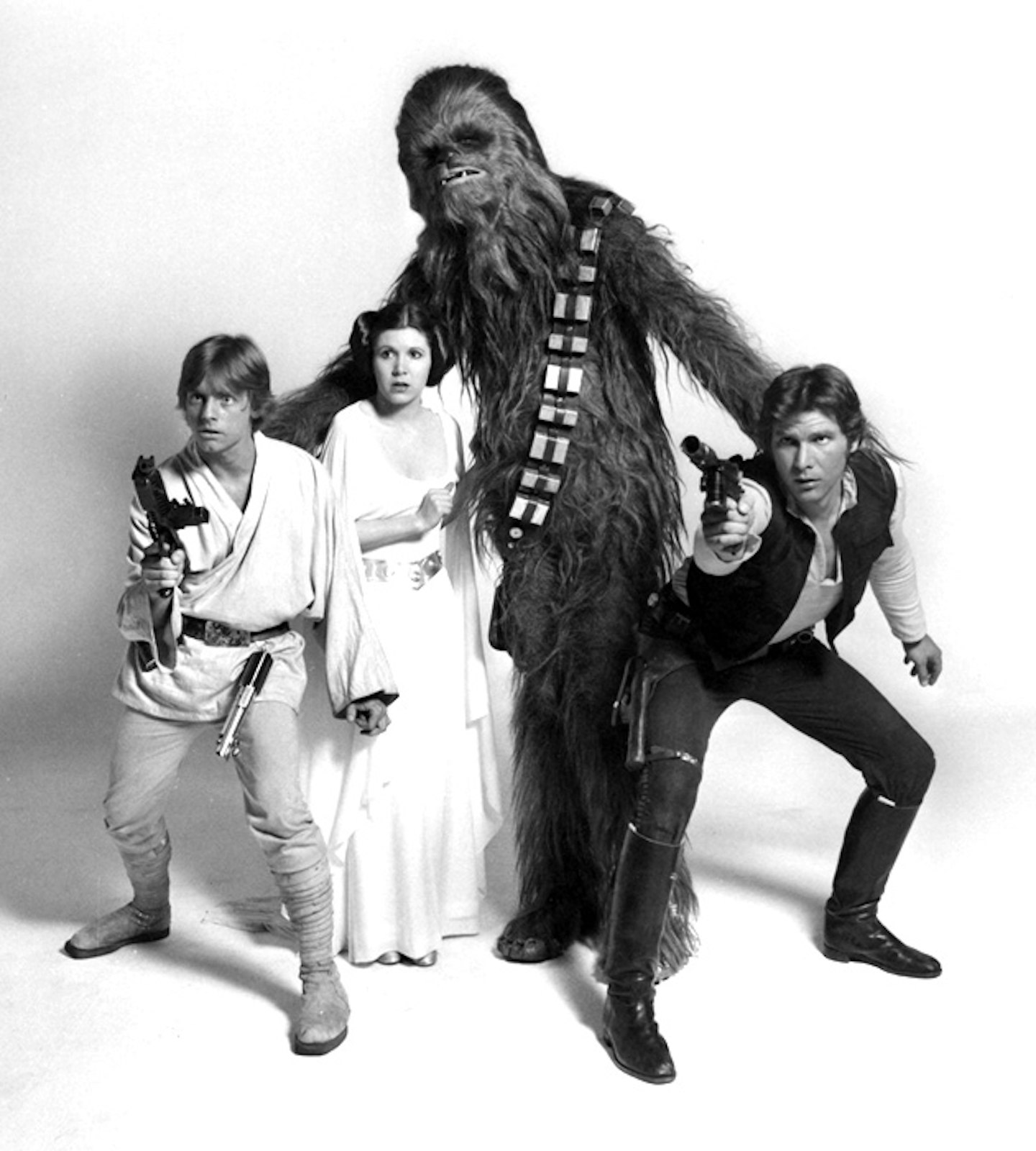

I was one of the few people who thought it was going to work, and I hadn't even seen any special effects. I just thought George had tapped into something primordial, some myth that I recognised the power of. The wise old warrior played by Alec Guinness, the callow prince played by Mark Hamill, the princess played by Carrie Fisher - and I knew that I was the rapscallion of the universe. And I thought it was funny. I always thought Star Wars and Indiana Jones were basically comedies. The humour came out of their relationships; it came out of the fact that we were basically types.

Were you ever wary of the number of special effects?

I've never been bothered by proximity to special effects and I've never felt disadvantaged by them. They're all part of a movie, and when the movie's under control I don't feel upstaged by them.

Is it true that you argued for Han Solo to be killed off in Return Of The Jedi?

I thought it was a good idea, to give the film some depth. I thought Han was dispensable: he had no momma, no poppa, no story. It would have been a good thing. George didn't agree.

Like the time you said to him about the script, 'you can't say that shit - you can only type it'?

Yes, and I was wrong. It worked.

How do you feel about Episode I?

Ohhh, that's not fair. It's a very different type of movie to the films we made, which depended on the relationships between three or four characters. George has moved on, and I understand and appreciate the efforts involved.

You're more closely identified with Indiana Jones. How did that come about?

George first approached me with the Raiders idea without a script. He very simply called up and said, "We've been kicking this idea around that you should play the part in Steven's movie." I should add that I wasn't their first choice. They'd wanted Tom Selleck, but he couldn't get out of his TV commitments for Magnum P.I., so I got the part by default.

How did you feel when you finally got hold of the script?

I thought it was wonderful. The only question I had in my mind about it was that, because both The Empire Strikes Back and Raiders were written by Lawrence Kasdan, there was some similarity in the characters. Steven agreed that we had to make a definition between the two, and not give Indiana Jones the kind of snappy, hip dialogue which belonged to Han Solo.

Who came up with Indy's look?

George. It's a strange thing, but George had some concept drawings made maybe two years before there was any thought of me doing the part. They were by an artist named James Steranko, and if you look at them alongside stills from the film, it's very striking, the similarity between the two. George insisted on the leather jacket and the wide-brimmed felt hat, even though we were in Tunisia in 120-degree heat. I kept saying, "Jesus, is there any reason for this suffering?"

Were there any other problems on that set?

Well, the main one was dysentery. That'll do it every time! That does spoil a nation for you, to see it from a toilet seat. It was just a very tough location, with all that physical stuff.

After playing Indiana Jones and Han Solo, do you feel burdened by the hero image?

It concerns me a little, though not for my sake. All it means to me is that I have a responsibility not to get caught doing anything terrible and thereby jeopardise my credentials. Not that I do terrible things, like running over dogs or anything like that. It just makes you think twice before you say or do things in public.

The final version of Blade Runner was something that I was completely unhappy with. The movie obviously has a very strong following, but it could have been more than a cult picture.

During the Star Wars trilogy, you took time out to make Blade Runner, one of the darkest films of your career. It's a widely-respected film, but you had issues with it. Why?

I was desperately unhappy with it. I was compelled by contract to record five or six different versions of the narration, each of which was found wanting on a storytelling basis. The final version was something that I was completely unhappy with. The movie obviously has a very strong following, but it could have been more than a cult picture.

It failed at the box office. Why was that?

I think audiences were turned off because they didn't have any emotional context for the whole film, including my character.

Do you ever worry that the range of characters you play isn't wide enough?

Yup. And I bumped on the edge with Sabrina, Regarding Henry and Mosquito Coast. But when a character is sufficiently different to the others the audience has seen me play, they get worried by it. They say, "The man's acting. He's acting now."

But surely that's your job?

The basic skill of an actor is, in fact, empathy, and that's maybe not a skill, it's a disposition. I am an assistant storyteller. I enjoy feeling useful to a team effort. It's my way of finding a use for myself, a utility in this world. So what I'm ambitious for is to not get caught 'acting'. I want to really feel the role and not let people see the process, or to let them stand back and admire it, because I think that does finally get in the way.

It sounds like you approach filmmaking as a craft, like carpentry...

There's a real simple analogy. You have to perceive it from the ground up. You have to lay a firm foundation, then every step becomes part of a logical process.

And you combined the two, literally, in Witness.

(Deadpan) You could say we took advantage of my previous experience.

Do you still keep your hand in with the woodwork and DIY stuff?

I haven't done any carpentry in over 20 years. It's one of those pieces of myth that persist well beyond their useful, appropriate life, because it seems like such a nice idea to have this blue-collar worker become a fairy tale prince. I have a workshop in Wyoming and I'm still interested in it, but I've lost a lot of the tool skills that gave me pleasure.

You like to get involved in every stage of the filming process, right from script stage. Does that cause problems?

For some directors, I'm the actor from hell.

When you made the Jack Ryan movies, you were instrumental in realigning Tom Clancy's creation, weren't you?

Clancy's Jack Ryan was less conflicted about what he does and how he does it. I didn't find that as interesting.

You tend to play good guys, however reluctant or understated, like Richard Kimble in The Fugitive. What kept you away from villains?

I prefer to be part of a positive statement. I'm not interested in the psyche of a serial killer. What I'm interested in is creating a situation in which people get some emotional exercise, which makes them feel like human beings and makes them understand that they are part of the human community with all its responsibilities. A bad guy in a movie has a lot of latitude for acting. He can walk up the wall, crawl across the ceiling, go piss in the corner and everybody will say, "Fantastic!" But somebody's going to have to catch that sucker. Somebody's going to have to play the guy who gets him in the end. And that's a better part.

The good guy roles reached the ultimate height in Air Force One, where you played the President of the United States. Were you being tongue-in-cheek there?

No, I wouldn't say that. I was given the script by the producers before a director was attached to it. It was not in its final form, but it obviously had the armature and plan for spectacular entertainment. Part of it was the genius of the concept of the President in that situation, but it was also the soul and nature of the President, his relationship with his wife and family, and the moral dilemma that he creates for himself.

I don't feel any lack of noble purpose if I do a film that's commercial.

So it's not an ironic comment on your movie stardom?

I don't take trouble at all to conform a screenplay to my iconography. I don't say, "We can't do that - the audience wouldn't accept it." I try to take the limitations of what is required to play a leading character and then screw with them.

Which you also did in What Lies Beneath. Although he's technically the bad guy, your character is still very human - more flawed than evil. After resisting villains for so long, why did you take the risk?

There comes a point when you've exhausted your opportunities playing good guys. I've been around long enough, I think I'm entitled to explore a bit. But what I saw there was an opportunity to play a character different from what the audience's expectation was. A chance to take their crude experience of me - of my iconography, if you will - and turn it on its ear at an appropriate juncture in the film to be useful to the process of telling the story.

Spielberg recently announced that a fourth Indiana Jones was definitely in the pipeline. You'll be 60 this year, and older by the time it finally goes into production. Won't this pose something of a problem?

Why? There is no barrier to Indiana Jones growing older. It's not an age-based character. (Pause) We can't bang him up as much as we used to, maybe. (Laughs) But I guess I can pretend to have the capacity as well as I pretended before.

At $25 million a film, you've more than established yourself as bankable star. Do you ever feel the urge to make an art movie?

I try to preserve a certain amount of time away from the movies, so I don't allow time to do those smaller parts that might give me an opportunity to do more seemingly 'artful' things. Although, having said that, I don't feel any lack of noble purpose if I do a film that's commercial.

You spend the rest of your time out of Hollywood altogether. Why did you choose Wyoming?

It sort of fit this picture I had in my head that I'd carried around for a long time. A picture of what the American paradise would look like. Woods and streams and stuff like that. Clear, mountain air... And I saw it.

Do you think it's important to have that kind of escape?

I think people only have so much interest in anybody, and if you barrage them in between the times you have something to offer them you become a personality rather than an actor - much more short-lived. I only work once a year. And that's enough.

This article was first published in Empire Magazine Issue #156 (June 2002).

Visit Empire's celebration of the Skywalker Saga for even more Star Wars content.