Less than four months away from the release of Spider-Man: Homecoming, Empire takes a look back at the Spidey adventures that might have been (and, in most cases, thankfully weren't).

A single glistening strand of a spider’s web bisects the BLACK FRAME. As CLASSICAL MUSIC caresses our ears, we see the strand criss-crossing others in a perfect orb web. A spider – black with an intricate pattern – drops INTO FRAME. It gracefully gathers and weaves the strands together….

Those words began the screenplay for the first Spider-Man movie, but not Sam Raimi’s 2002 film with Tobey Maguire in the lead role. In fact, the actor was all of ten-years-old when screenwriters Ted Newsom and John Brancato first presented this particular script to [Stan Lee](http://www.empireonline.com/people/stan-lee/

). And it would be seventeen years from then before the character reached cinemas.

In the early 1980s, Lee was growing increasingly anxious that Marvel’s numerous properties were not being exploited on film or television in the way that DC’s had (hard to believe such days existed). Marvel, he felt, needed something special, and he believed he had found it in Newsom and Brancato.

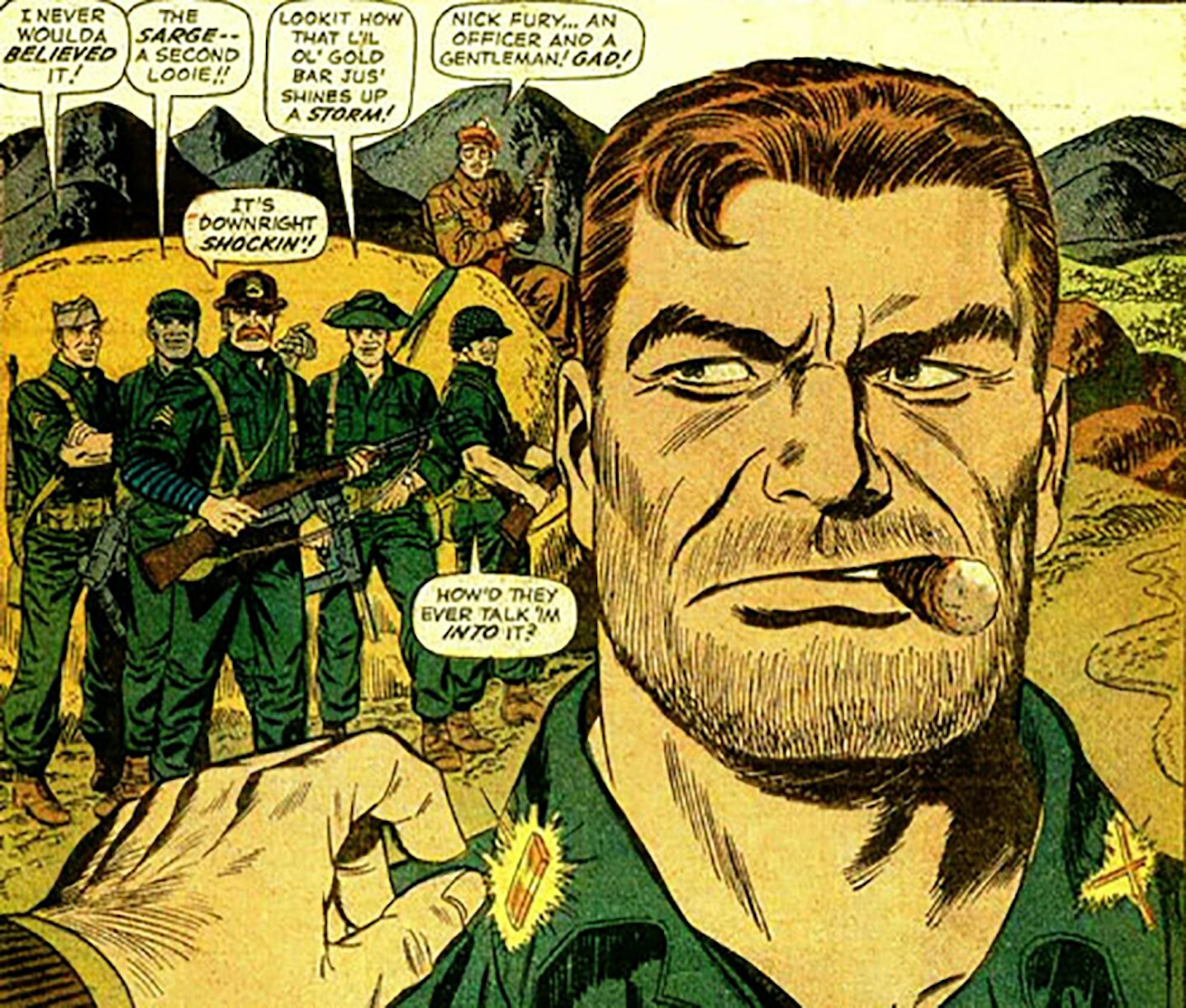

The duo were a pair of writers that were determined to break into Hollywood and felt they had found a possible inroad through a developing friendship with Lee. Intrigued, Lee hired them to pen a screenplay adaptation of the old Marvel World War II title, Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos. The plan was that Lee, armed with the screenplay and comics, would make the studio rounds to see if he could drum up some interest in the property.

Ted Newsom (Writer): "We did the Sgt. Fury script, which Stan loved. Then he asked us what we’d like to do next and we immediately said, 'Spider-Man.' He said we couldn’t do it, because Cannon Films had the rights to the project."

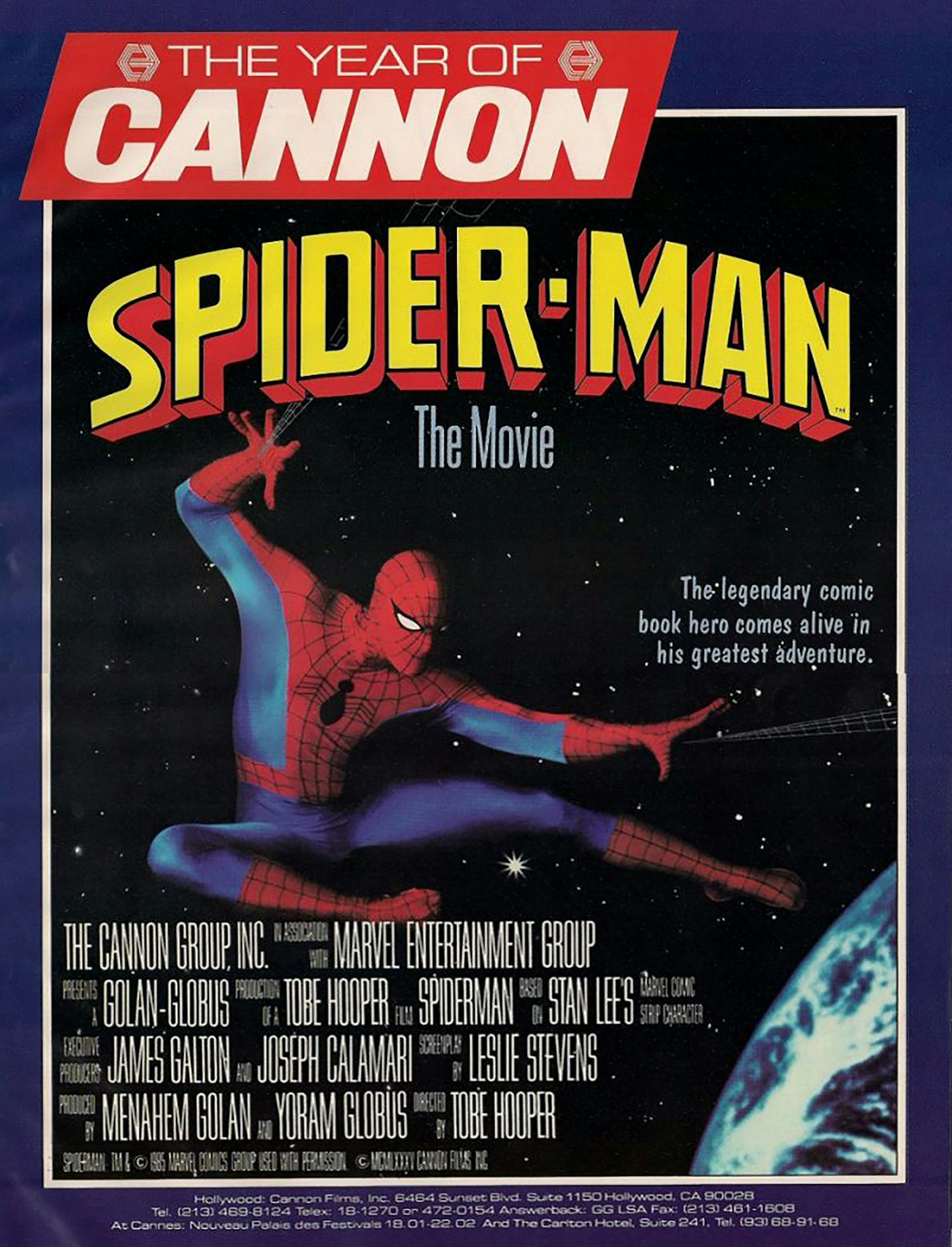

Cannon’s beginnings can be traced back to 1979. Israeli cousins Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, who had achieved great success in their homeland, were able to take control of Cannon when it was a minor independent that had specialized in exploitation films. Under the guidance of Golan/Globus, Cannon would come up with titles they planned on producing, attach as many big names as they could in terms of actors, writers and directors, and sell the projects to different international territories, thus guaranteeing a profit before a foot of film had actually been shot. If you were able to find a copy of Variety or The Hollywood Reporter from the period, you would probably be stunned by the sheer quantity of ads Cannon took out to announce their projects, most of which never saw the light of a cinema projector. And those that actually were filmed, often ended up colossal box office failures.

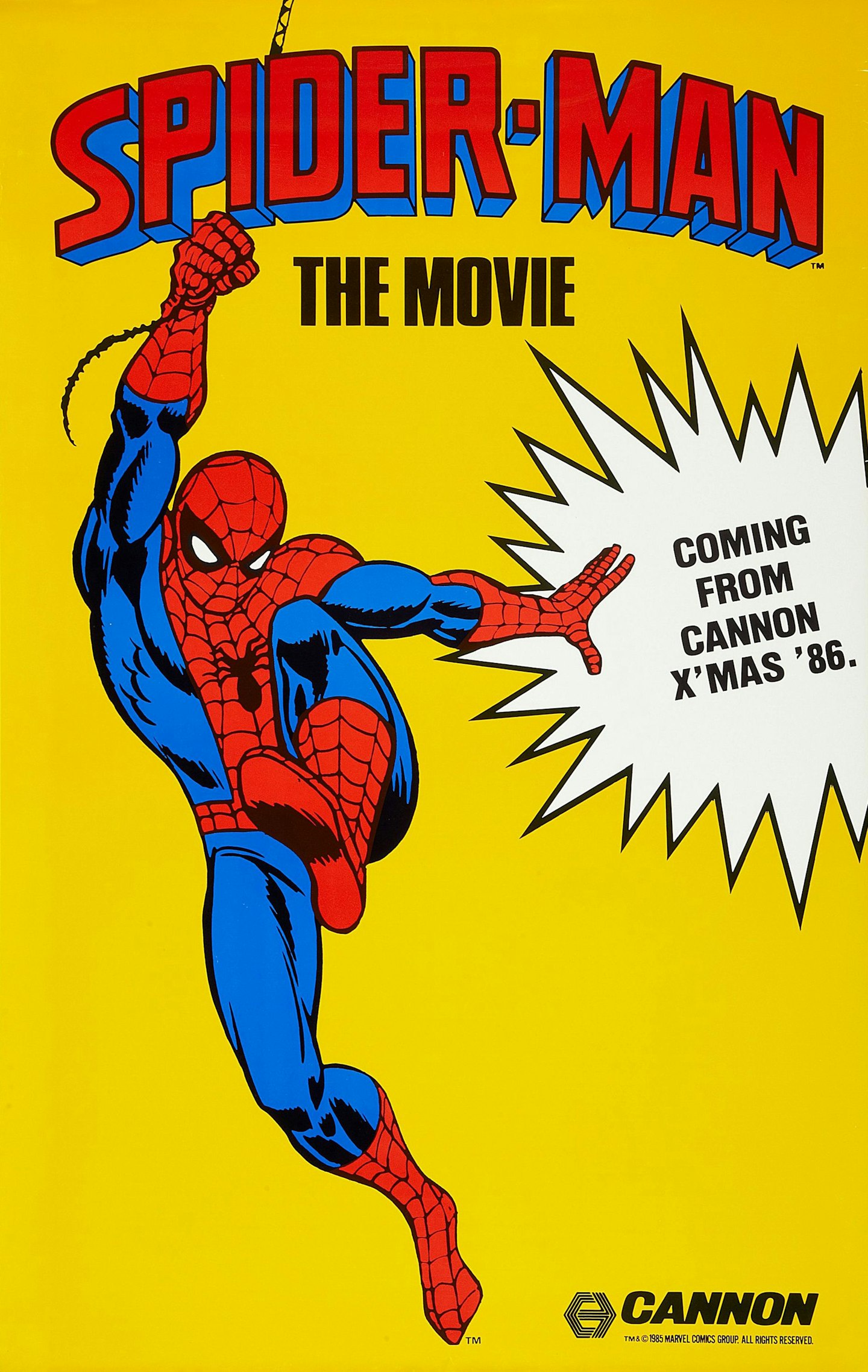

John Brancato (Writer): "There were a number of cheese-ball cheapo production companies that, during the eighties, decided that they would turn themselves into studios. Instead of making B-list pictures, they tried to make the serious money A-list pictures. Cannon was one of them and one after the other they failed. New Line, New World, Vestron — they were all the same. But Cannon was a pretty magnificent flame-out. They didn’t have the best tastes and got involved in financing a lot of lame projects. They built themselves a nice fancy office and I remember going to the opening of the building and there were Spider-Man promo posters everywhere. Within six months, though, everything had fallen apart. It was the meteoric rise and fall of Cannon."

One big-budget flop followed another, beginning with Tobe Hooper’s remake of Invaders From Mars, Masters of the Universe, based on the He-Man toy line; and Superman IV: The Quest for Peace, whose thirty-five million dollar budget was cut in half on the eve of production, resulting in the worst entry in the series and the end of Christopher Reeve’s turn as the Man of Steel. Fiscally exhausted, it was only a matter of time before Cannon’s collapse would be complete. But in 1985, Golan and Globus felt that the superhero genre still hadn’t been fully exploited, so Golan negotiated with Marvel Comics to option the feature film rights to the Spider-Man character. In the end, Cannon paid Marvel two hundred and twenty five thousand dollars plus a percentage of gross revenue for a five-year option.

Satisfied with the deal, Golan, who never truly understood comics in general or Spider-Man in particular, hired Outer Limits creator Leslie Stevens to write a film treatment. The result was a story in which Peter Parker works as a photographer for the Zyrex Corporation. The owner of the company, identified only as Dr. Zyrex, performs an experiment on the unsuspecting Parker by bathing him in radioactive waves. The result is not the acquisition of spider-like powers, but, instead, a transformation into an eight-legged human-tarantula hybrid. For the rest of the story, Parker had to battle one mutant after another. That’s where Newsom and Brancato stepped in.

Brancato: "Once Cannon hired us, Stan suggested we write the script from his outline — which was about two pages long and more or less dealt with Spider-Man’s origin."

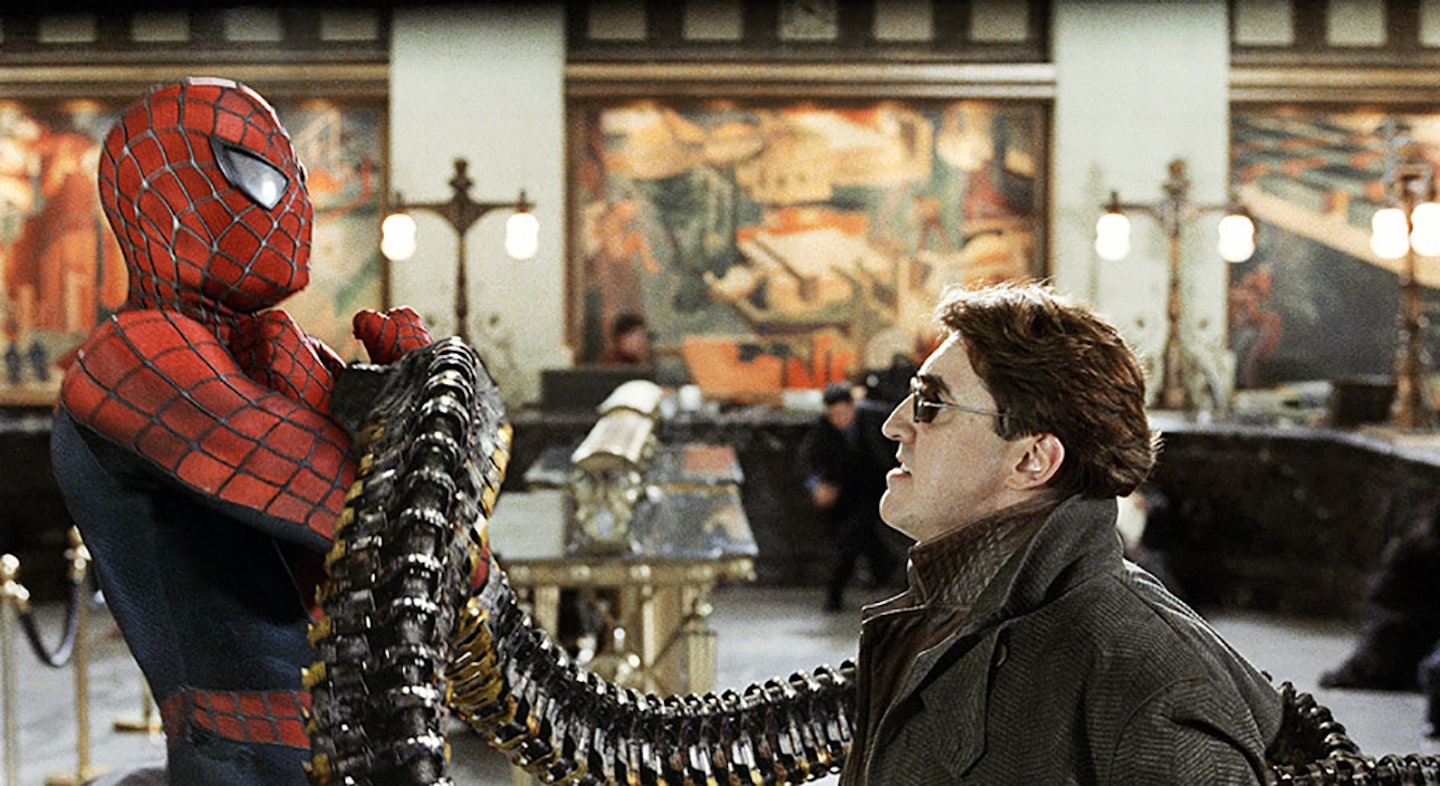

From the outset, the duo pitched a story that differed from the comics in that it intertwined the origins of both Spider-Man and Doctor Octopus. In their scenario, Doc Ock’s experiments results in his being physically altered and joined with his mechanical waldos, and Peter being bitten by an irradiated spider and transformed into Spider-Man. The rest of the origin plays out pretty much the way it did in the comics, though an attempt was made to keep a sense of realism to the characters in terms of their motivations and reactions to things. Admittedly, though, things get a little fanciful at the end when Doc Ock’s experiments involving anti-gravity results in the science building at Empire State University floating high above the ground as hero and villain battle it out.

Newsom: "We took the approach that we couldn’t presuppose anyone knew anything about these characters. So what you had to do was a creation story, and if you were going to have a super villain, you had to create him, too. It can’t just come out of nowhere. So Stan had a treatment from which we worked our story. We made alterations and changes. Cannon approved that treatment and we started scripting from there."

Brancato: "The problem with any superhero comic, obviously, is to try and find the right tone. Spider-Man, unlike Superman, always had a tongue-in-cheek, self-conscious approach to itself. It was difficult to capture that and make it play as a satisfying action film. In a lot of ways, Spider-Man was a parody of Superman and all the other books of the time. Peter Parker, being a self-conscious, socially unsuccessful, somewhat nerdy character, is very different from a square-jawed hero. Clark Kent has some similar attributes, but Spider-Man had a much more self-conscious humor about the whole situation. The villains were pretty self-conscious and goofy. If you read those stories, they have a very different tone from the DC Comics at the time. Marvel really did put itself up as being for the slightly brainier audience out there. From the very beginning, the Spider-Man comic is laughing at itself. A lot of it is asides to the audience and everything done with a wink, which is the style Stan mastered.

"It’s one of the reasons Spider-Man was so lovable. But it was also a tough tone to capture. That was always the challenge of it. Superman: The Movie was so mythic and grandiose in the way it was presented, and Spider-Man could never be that. It was always the younger brother to that storyline. It didn’t take itself as seriously."

Ted Newsom: "The one thing that John and I didn’t agree with Stan on was his take on villains and superheroes in general. I say this with due deference, because I owe a great deal of whatever we got going to Stan. But in his story, Doctor Octopus has this horrible accident and he has these waldos placed invasively into his body. As a result, he goes crazy and decides to become the greatest master criminal in the world. Well, people don’t do that. That’s not the way real people react. If you’re in an accident and you lose a leg, you don’t decide to become the greatest pirate the seven seas have ever known. That is not a rational, logical or even understandable emotional leap from where you were."

Lee remained steadfast in his feeling that Doc Ock should have his accident and come out of it with a lust for world conquest.

Newsom: "Nothing’s wrong with that if you’re doing a comic book. One of the blessed things about Marvel and Stan’s work in particular, is that there was an element of sophistication about it that hadn’t been present in comic books before that. And a depth. So we tried to stay with that. Look, is James Mason the villain of North by Northwest? He’s the antagonist, but if you sat down and asked him, he would not say he’s doing bad things. His goals are absolutely pure as far as he is concerned. Most anybody, if you ask them, unless they’re sociopaths, will tell you that their goals are pure. You have to have somebody like that as a villain if it’s supposed to be anything else but white hat/black hat. We tried to keep the character human, despite the fact that he’s an odd mutation."

Brancato: "All of the Marvel villains, especially in Spider-Man, were sort of shaded and you sympathized with them in the same way that the heroes were less perfect. It gave warts to the whole world of superheroes, which was so much of the appeal of it. Spider-Man from the beginning had elements of this sort of Batman-like origin. He is self-serving and his uncle gets killed by the same villain he let go, because he didn’t give a shit. There is definitely a darker strain all the way through on Spider-Man. We tried to get that across, and the idea of Doc Ock being kind of a scary monster."

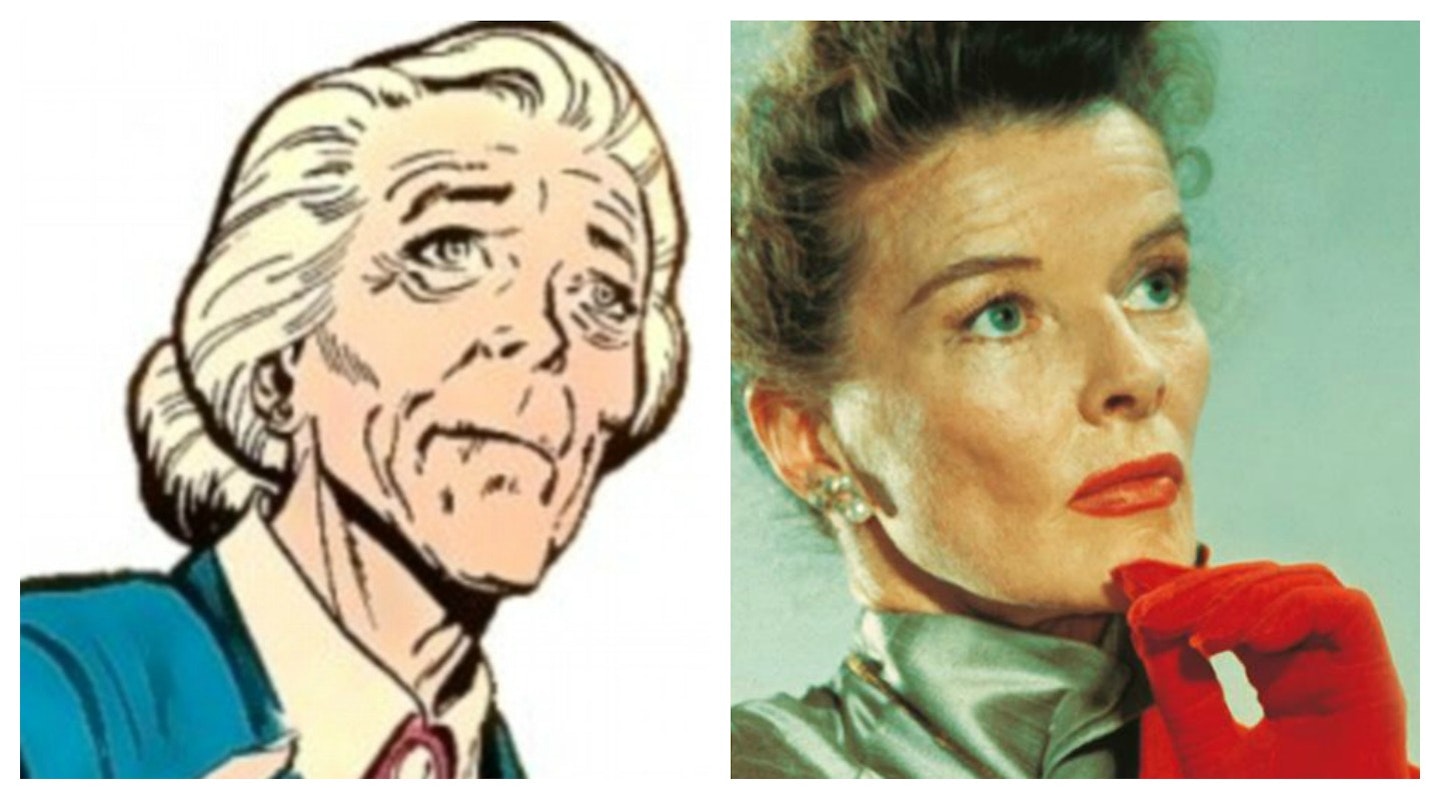

Newsom: "One conscious change we made was to alter the character of Aunt May, changing her from someone who is a pain in the ass that looks like she’s about one hundred and fifty years old to a woman more in line with Katherine Hepburn. We made her very hip. Think Katherine Hepburn and you suddenly had a much more fun dynamic, because Peter Parker is not the hippest guy in the world."

Next to join the project was director Joe Zito. A New York native, he'd proven himself an innovative director by taking relatively low-budget films and providing them with a sense of scope despite limited resources. His success with Paramount’s Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter (1984) caught the attention of Golan, who brought him on board to direct the Chuck Norris action film Missing in Action, first in a wave of “return to Vietnam” adventures along the lines of Uncommon Valor and Rambo: First Blood Part II. Quickly becoming Cannon’s most profitable film ever, Zito next helmed 1985’s Invasion USA, another Norris adventure in which the cinematic hero battles terrorists who bring their war to American soil. Enjoying near-equal success to MIA, that film secured Zito with his choice of Cannon projects, and he immediately focused his sights on Spider-Man.

Joe Zito (Director): "I had been doing comic book type movies and I liked those strange, dark worlds. There was no Batman movie yet, remember, and I had this vision of having this dark world with Spider-Man being the burst of color at the center of it. We had wonderful designs for the film. It was going to be a very stylish movie and my conversations with Cannon was that I had really made my films with them with very little input — situations where they pretty much just funded the projects — and I didn’t want to be interfered with. I told them that Spider-Man in particular had to be done completely differently from the way things had been done before. We would be bringing in a British crew — a very high-end British crew — and I was supposed to shoot in England, but by the time we got our production far enough along, Sidney Furie was going to do Superman IV on the stages in England, so we moved to Rome."

Zito points out that the excitement of the project was that he would be dealing with a character who is conflicted and had to deal with real dilemmas.

Zito: "He had to save the world, but on the other hand, he couldn’t get laid. He was struggling through school. It was fun and real and it was a way to take something that was such solid comic material and have it touch the world. It wasn’t like Superman, who had no moral dilemma. He was completely conflicted. I loved it and I was not a Spider-Man buff as a kid. I was in a good place at Cannon at that point. I felt that if I asked the company for something, they’d let me have it."

Including his own writer. Although Zito initially began working with Newsom and Brancato, it was obvious that that the three didn’t quite see things eye to eye.

Brancato: "He didn’t really seem like a powerful creative force in the process."

Rumors are that the writers, for whatever reason, pretty much ignored Zito’s efforts to inject his vision into the script and, as a result, were replaced by Barney Cohen. The fit was a good one, considering that Cohen had written Zito’s Friday the 13th Part IV: The Final Chapter, and would go on to create the vampire TV series Forever Knight and adapting Sabrina the Teenage Witch.

Barney Cohen (Writer): "When I was asked by Joe Zito to rewrite the script, they flew me out to Los Angeles from New York, where I stayed for three months. During that period, I read dozens of Spider-Man comic books to familiarize myself with the character. Then we had a meeting with Menahem Golan and I realized that he hadn’t familiarized himself enough with the character to understand him the way Stan Lee did. One of the problems with the Newsom and Brancato script, which I made worse in Golan’s eyes, was the character’s duality. What I mean by duality is that he would rescue somebody, and then garbage would fall on his head. Then he couldn’t get a date and things like that. Menahem went nuts when he saw my first draft, because he thought I was doing exactly the opposite of that. He really saw Spider-Man as a young Superman in a different outfit. I don’t know if Menahem would know Superman as a socialist realist hero, which he was. He just did not get the duality and it was very difficult to explain to him why Spidey is self-deprecating, why garbage falls on his head, why he swings on a web and lands on the wrong thing. He just didn’t get it. That wouldn’t happen to Superman. Finally, Zito, who did get it, convinced him and we ended up with a pretty good script."

Dated April 1, 1986, Cohen’s script, to a large degree, followed the structure of the Newsom/Brancato draft, although there were several additions. Most notable among them was that Doc Ock had suddenly developed an underling — Weiner — who performed burglaries for the good doctor in an effort to drum up some extra cash. During one such burglary, Weiner killed Peter’s Uncle Ben, thus tightening even more the origins of and connections between Doc Ock and Spider-Man.

Twenty days later, Golan himself handed in his own pass on the material, resulting in a script credited to him, Cohen, Newsom and Brancato. This version of the story was fairly similar to the April 1st draft, though Golan added some odd topical references (i.e. the Hillside Strangler) and dialogue.

Newsom: "Here’s a for instance. There’s a sequence where Peter Parker is first realizing that something is wrong. He’s gotten bitten by the spider and he’s surging with radioactive Spidey power. He walks onto the street, a truck barrels at him and he leaps, finding himself four stories up. Then he climbs to the top of the building and tries to figure out what the hell’s going on. Now that’s comic book stuff; that is precisely what happens in the Spider-Man origin, which is why we used it. It’s perfect the way it is. But Menahem added other things that were way out of character for Peter Parker, i.e. Spider-Man, to do, because Menahem didn’t grow up with the thing. He didn’t understand who this character was. This guy was more Charles Bronson than Peter Parker. You have specific things that Peter Parker would say, do or think, likewise Spider-Man, because you’re talking about the same guy. He wouldn’t just beat up on a guy because he looked sideways at a girl. That’s not what Spider-Man would do. But Menahem didn’t see that, because he didn’t grow up on this shit. What John and I tried to do is keep the essence of Peter Parker there and keep what we thought was fun about the character."

Cohen: At that point, stars and funders would come by this particular office we were working out of, because Spider-Man was the twenty million dollar movie. This was a major motion picture. We were like a stop on the tour, we were credibility. The interesting thing is that most of these people would come by because they were interested in Spider-Man and they all knew the character better than I did. To be honest, though, the whole experience was just a lot of fun. But then, Menahem told Joe that he had to lower the budget.”

Zito: "About one and a half million dollars had been put into the film’s development at that point. Then Cannon started getting into financial difficulty and they started limiting the amount of money. As an edict from the bank they had to limit their budgets to five million dollars per picture. We didn’t have to spend five. Originally the studio thought it would cost thirty million dollars. I think we actually budgeted it in the upper teens, but thought it should cost more. Then I got a phone call asking if I could do it for fifteen million dollars.

"We had a five million dollar effects budget back then. We were talking to Richard Edlund about doing special effects. Then I got another call when they were going through even more difficulties with banks and that kind of thing. They asked me to come back to Los Angeles from Rome. I went to Golan’s home. There I met with Golan, Globus and the head of production. Globus said, ‘I have ten millions for your Spider-Man.’ I said, ‘Ten million? Look, we’ve got a five million effects budget. You’re kidding yourself. You can’t make this movie for ten million. If that’s all you can spend, you ought to not make this film.’ Ten million is a lot of money and you could have made a real good film for that amount of money. Maybe two really good films. But not Spider-Man with the level of effects you would need to make it competitive as an A-level film that you’re going to base the value of a company on. So I advised them not to do it and that’s how we didn’t do it. But they would always say that they should have made Spider-Man, because it was going to be their Batman — it was the film that was going to change the value of the company. Unfortunately, it came at a time when they could not afford to make it. Had we gotten the thing off the ground six months earlier, we would have made the film and it would have changed Cannon. The film we had in mind was a film that would have worked."

Unfortunately, by 1987 not much was working for Cannon. Not only were there the aforementioned box office failures to be dealt with, but the studio had apparently overstated the value of its stock and was being investigated by the Securities And Exchange Commission. All indications were that Cannon would be going bankrupt, until it was taken over by Pathe Communications, Giancarlo Parretti’s holding company, whose presence would most definitely be felt over the next few years, most notably in terms of the acquisition of MGM.

Zito: "In 1988, Menahem turned his attention to Spider-Man and decided to go a less expensive route. The idea was that they would do a cheap version for a couple of million dollars. Albert Pyun had been directing these low budget films with Cannon that looked really stylish. They thought, 'Well, we own the property anyway,' because they had the option on the rights and they thought to knock it off as a low-budget picture."

Golan turned to actor/writer Don Michael Paul to tackle the next draft of the screenplay, and his was the most drastically different from the Newsom/Brancato draft to date. While the origins of Spider-Man and the villain are connected, Doc Ock is nowhere to be found. In his place is the Night Ghoul, a hybrid between a human and a vampire bat that was created via genetic manipulation. While the Night Ghoul seems like a mindless creature, it’s ultimately revealed to be an altered scientist who has set about avenging the deaths of a group of other scientists who were brutally murdered. While the characterization has a lot in common with many Marvel villains — whose external appearance belies a more sympathetic soul — the script itself was fairly violent and bloody. And it was still too expensive.

](http://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/part-2-spider-man-cannon-cameron/part-2-spider-man-cannon-cameron?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)