This week sees the debut of Empire’s stunning Hobbit issue, and to get you in the mood to head back to Middle-Earth we’re reprinting some classic Empire features on Peter Jackson’s first Tolkien trilogy. Today, here is Ian Nathan’s piece on The Return Of The King, originally published in issue 175.

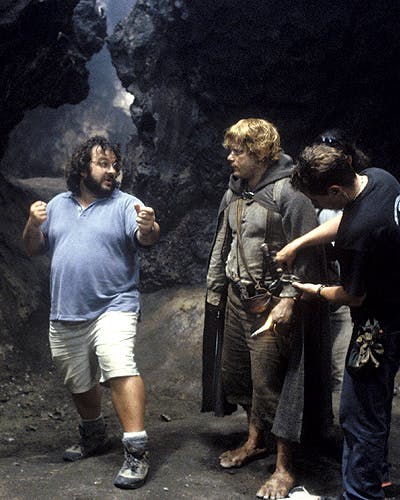

"THIS ," OUR TOUR GUIDE ANNOUNCES, "IS SHELOB'S LAIR!" We are gazing into the mouth of a deep-set cavern smothered in lank webbing, sticky and moist to the touch, and scattered with skeletal bric-a-brac that suggests the twisted hulks of Orcs. “Isn’t it cool?” Well, yes, it is. Transposed from the end of book two to the beginning of film three for the sake of dramatic thrust, this geo-organic sepulchre is the location for one of the trilogy’s most horrifying and exciting encounters — the mismatched battle between intrepid Hobbit heroes Sam and Frodo and the swollen, impossible hulk of Shelob, a ravenous female spider who stands between the ringbearer and Mordor. Like so much in these films, it’s just so right.

The trip around The Return Of The King’s sets, shuffled and crammed into every nook that Wellington’s Stone Street Studios can offer, has reached a culmination. The skin of the cave is pot-marked with small indentations carved out of the tough polystyrene. “That’s the result of her excretions,” says the unit publicist who has been leading Empire around. There’s something appealingly quaint about the way everyone refers to the details of the plot as facts rather than moviemaking subterfuge. “It’s acid, and she’s been rubbing up against the walls for so long, they’ve started to dissolve. The detail makes it so real,” she sighs, as if nothing on this set can ever stop amazing her. Perhaps it can’t.

Realism is the scaffolding on which the trilogy was built. Despite its fantastical setting and grand mythology that never was, the guiding principal for Peter Jackson and his team has been to make it history. “It’s what has pleased me more than anything else,” the director claims. “That people truly believe in these films.” And when it comes to a giant spider, created entirely by computers, they are going to carry on believing.

The anticipation for The Return Of The King is comparable only to that that preceded the return of Star Wars after 22 years, in the crooked shape of The Phantom Menace. But there are no concerns of a repetition of such disappointment here: the first two parts of the Rings adventure were met with adoring reviews, Best Film nominations and a ring-a-ding-ding at the box office. The all-out love building for the conclusion to the epic story is one fuelled by confidence. No-one expects them to falter at the last hurdle.

Except this spider has been a tall order. Peter Jackson, master of zombie-horror, purveyor of Nazgûl, Uruk-hai and Balrogs, and conqueror of Hollywood, is a big girl’s blouse when it comes to tiny little arachnids. “Oh, I hate them,” he confesses. “Always have.” There’s a story to this. The boyhood Jackson would love to play Matchbox car crashes on the earth banks beneath his house — that was, until he dug up a nest of irritable spiders. Years later, when he called upon best friend Richard Taylor (now head of Weta Workshop) to help clear a garage, it was only because the place was infested with spiders and the chronic arachnophobe wouldn’t go near them.

“We just enjoyed playing it up and throwing these spiders at him,” laughs Taylor on his boss’ delicate foibles, “and I’ve always remembered that. So when we came to design Shelob we basically delved into what gave him the heebie-jeebies!”

The main offender is yet another Kiwi native — the Tunnel Web, a spider that has become the blueprint for their lady. “She’s always been depicted a bit too science-fiction for my liking,” Jackson says. “There is a tendency to make her look more spiky, like a crayfish or something. I wanted something organic, so we hit on Tunnel Webs — they were always the spider I was most scared of. It’s just the way they move — they scuttle and then freeze. Everything about spiders that scares me is in Shelob’s performance.”

%20%20*%22%20Everything%20about%20spiders%20that%20scares%20me%20is%20in%20Shelob%E2%80%99s%20performance.%22*%20*Peter%20Jackson*%20%20%20Co-writers%20Fran%20Walsh%20and%20Philippa%20Boyens%20delighted%20in%20the%20fact%20she%20was%20female.%20They%20really%20got%20into%20the%20idea%20of%20some%20deep-seated%20Freudian%20rupture%20in%20Tolkien%E2%80%99s%20subconscious.%20%E2%80%9CAre%20you%20kidding?%E2%80%9D+cries+Boyens.+%E2%80%9CThe+boy-Hobbits+have+to+enter+this+long%2C+dark+tunnel+occupied+by+a+hairy+beast.+Peter+kind+of+pulled+us+back+from+that%21%E2%80%9DDespite+a+last+minute+rejig+to+muscle-up+the+beastie+%28Jackson+wanted+a+scarier+mouth+and+eyes=&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

One famous chapter from the book, The Ride Of The Rohirrim —starring those ZZ Top horsemen from The Two Towers — looks set to be the most cymbal-crashing, blood-stirring sequence since Chuck Heston hung up his sandals. Over 6,000 horses will charge into the body of the dark army, a suicide mission created by filming 250 horses for real, and then bulging their numbers with motion-captured CGI steeds. “They put out this call for riders,” recalls Karl Urban (Éomer), “and they came from every corner of the islands, gathering on this plain, putting up tents and building camp fires. It was amazing, like some kind of Woodstock. And the next morning they all charged together. Just extraordinary.”

Clutching for realism in these fantastical images has tested the various effects departments to their limits, and they’ve not been found wanting. Requests would fly in for 1,000 skulls by, like, tomorrow. “Pete was shooting the Paths Of The Dead sequence,” explains Taylor. “He just didn’t have enough skulls, so we had to produce a batch more on the spot.” All part of a day’s work for the fantasy factory that is Weta Workshop. Indeed, one particular skull now adorns the handlebars of ‘Pete’s Bike’ — it says so on the crossbar, the one the director uses to spin between sets to save time.

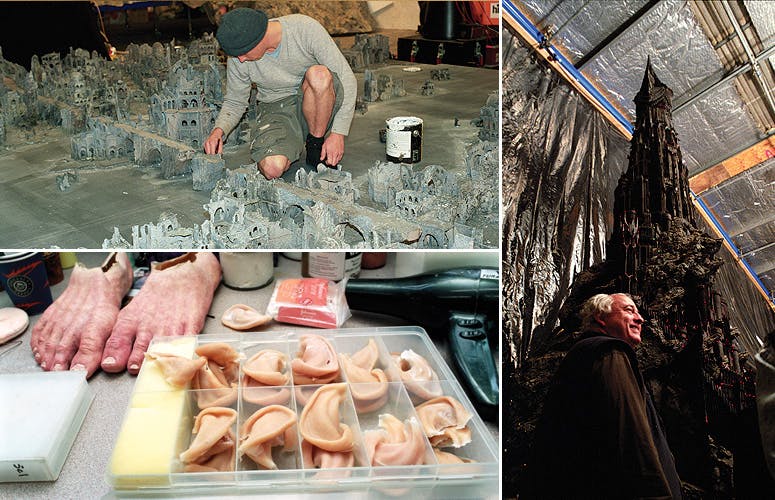

As of June 2003, the poor Miniatures Department still have over 200 shots to complete, and keep having to stop work to mend the intricate models that were packed away for the third film. The breathtakingly detailed miniature of seven-tiered citadel Minas Tirith requires constant attention, like some sort of elaborate Airfix model for anal deities. There’s no doubting how good the results will be, but the miniatures team, like Frodo and Sam, haven’t even got to Mount Doom yet. “The Mount Doom model is still in storage,” moans a lieutenant. “When we get around to opening the box, I just hope it’s still in one piece!”

ELIJAH WOOD IS SOUND ASLEEP**.** Lighting rigs are being repositioned, walkie-talkies buzzing furiously, and Fran Walsh, Peter Jackson’s wife and cohort, is chatting intently to Andy Serkis, but nothing is disturbing Frodo’s power nap at the back of the set. “Oh, he can sleep anywhere,” says Sean Astin, who is taking the brief lull between set-ups to chat to Empire. Astin, dressed in Samwise’s familiar battered breeches, can’t seem to keep away. At every available juncture, he’s up on his hairy feet to finish whatever latest rumination is on his mind. “It’s what Elijah does to pass the time,” he explains. “I swear he used to sleep standing up when we were having our feet put on.”

The scene in question is another of those juicy Gollum moments, with Serkis on-hand to fill in the devious urchin’s oily movements for motion capture and ultimately state-of-the-art animation. Suspecting treachery is afoot, Sam is threatening, as the script so graphically puts it, “to stove his head in”. Relations have reached an all-time low between the tormented guide and “fat Hobbit” on the road to Mordor. A visibly deteriorating Frodo is raggedly trying to keep the peace, and Shelob lies in wait.

Right now, though, Astin wants to talk about Star Wars. He’s been a lifelong devotee but, akin to his deteriorating relationship with Gollum, he’s currently got the hump. “I met George Lucas at the MTV Movie Awards,” he recalls. “He’s a hero of mine, but he was like, ‘Yeah, hi,’ and turned away. I’m like, ‘Hey, I’m Sean Astin, you know… Sam.’ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘all you Hobbits look the same to me.’” Astin pulls a lemon face and then, wheeling away from the anecdote, coughs into his fist, “Yeah, and Jar Jar sucked, man.”

Fran Walsh calls for positions and Astin pulls away. “I’ll be right back,” he hollers as he scampers away to finish his scene with Gollum — Oscar-winning special effect Gollum, that is. Walsh has got a reputation as a hard taskmaster. She pushes for repeated takes, seeking out a perfection beyond even her husband’s exacting standards. Billy Boyd has re-christened her ‘Franly Kubrick’ in honour of her methods. “It’s about getting those moments right,” says Wood seriously, upon waking. “To get those minute details right on an emotional level. I really like working with her, you discover things together.” But, for Frodo, that means staring right into the abyss.

“You’ve got to see where Elijah and Frodo go in the third movie,” Astin says of his onscreen charge. “The power of the ring is almost physically pulling him apart. Elijah is going to these really demanding places.”

The warnings have been loud and clear from the Rings camp — this third film is going to be devastating, wrenching those tears from your vulnerable eyes by force if necessary. By the time we’re crawling through the ash and poisonous fumes of Mordor, the bucolic cuteness of Hobbiton will feel like decades ago.

%20*Building%20The%20Return%20Of%20The%20King:%20A%20technician%20prepares%20Osgiliath%20(top%20left).%20An%20ear-ful%20of%20Hobbit%20prosthetics%20(bottom%20left).%20The%20Barad-D%C3%BBr%20biggature%20(right?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

“The thing about the ring is that, once it gets its talons into you, you’re completely obsessed with it,” says Wood. “You become incredibly suspicious of everyone around you, and in this case, that includes Sam. Frodo becomes a shadow of himself. It starts to weigh down on him physically, too: it affects his breathing, it affects his overall energy.” Conversely, the now wide-awake Wood himself couldn’t look healthier, his large blue eyes matched by an easy grin. Out of costume he looks younger, slipping back to his humble 22 years, chatting and goofing in his native Californian dude speak. “Wow, it’s gone beyond what I expected,” he announces on the experience of playing Frodo. “I thought it might be an adventure, but it’s been more than I could have imagined.”And that includes the magnitude of the public response to something both magical and incomprehensible. The same goes for Astin — the level of obsession has taken on an unwieldy, unreal quality, as if the everyday world has become stranger than anything Middle-earth can offer.

“It’s totally overwhelming,” he confesses. “You can talk about it like it’s an idea, but it’s impossible to describe. Getting on a plane with your picture on it, you know what I mean, and walking down the street… I occasionally need to just close my eyes and take a deep breath.”

%20%20*%22He's%20really%20focused.%20He's%20on%20some%20speed.%20He%E2%80%99s%20taken%20some%20of%20Gandalf%20The%20Grey's%20pills.%20There%E2%80%99s%20no%20messing.%22*%20*Ian%20McKellen*%20%20%20A%20few%20Tolkien%20miles%20away%20(a%20rather%20elastic%20distance,%20which%20takes%20weeks%20to%20traverse%20but%20any%20available%20hill-top%20presents%20a%20view%20of%20the%20entire%20place?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

McKellen likes to keep a subtle distance from the unmitigated enthusiasm. He couldn’t be more pro-movie, but is willing to concede the characters are mostly drawn in storytelling terms than true refractions of humanity. “I sometimes wish the relationships were more complicated, but they’re not in the book,” he says. “That’s where you have to trust the director. He’s got the whole project in his mind, and the last thing you need is some deepening in a relationship that might detract from the sweep of the story.”

That said, he is still big on the parental theme that ripens throughout The Return Of The King, Gandalf as father figure to so many of the characters: “Obviously with Frodo, and particularly now Pippin, but also towards Aragorn, whom he has had faith in from the word go.”

How could we forget Aragorn? After all, the third film is named after his particular narrative arc, stepping out of the shadows and taking up the royal throne of Gondor. “It is not only about confronting what others expect from him,” drawls Viggo Mortensen on Aragorn’s groove. “He has become good at hiding who he is, operating under disguises. Finding himself is the biggest challenge, much more than fighting battles, dealing with the temptation of the ring or any of his difficult choices.” As has been well documented, Mortensen had a spiritual hook-up with Aragorn since he first sloped off the plane, and as he fictionally rises to fulfil his destiny to become a leader of men, he’s also become leader of the cast.

“We’d all be lost in the desert if that was the case!” roars Bernard Hill, who returns as King Théoden. “I suppose Viggo’s a leader by sheer dint of his personality. He’s been an example to us all, he’s a massive workhorse.” If Jackson has garnered most adulation from his cast, then Mortensen comes a narrow second. They all, to a man, Dwarf, Elf, Wizard and Hobbit, love him. All those unending talents married to self-effacing grace. Rings would not be the films they are without his lynchpin of conviction. “We’re not jealous at all,” laughs Hill. “He’s just a great guy and he’s my friend.”

Indeed, they formed a club — The Cunty-Bago Club. The two actors, along with Orlando Bloom, shared a make-up Winnebago, and through hours of beard and pointy-ear application formulated the rules of their society — most of which boil down to getting gossip and posting it on.

“For propriety’s sake it was called the C-Bago Club, because you couldn’t put Cunty on the call sheet,” Hill explains. “Sean Bean came in, Liv was also a part of it. As soon as I get back to England I’m going to start the C-Bago web site: Orlando will do fashion and Viggo will do current affairs. I’ll probably do gossip — you know, the social calendar. Liv will do Hollywood and Sean Bean will do the art of war. It’ll be our little corner of the world.”

%20*Aragorn%20(Viggo%20Mortensen)%20fulfils%20his%20destiny%20(left).%20Samwise%20(Sean%20Astin)%20on%20the%20brink%20(top%20right).%20The%20Battle%20of%20the%20Pelennor%20Fields%20in%20full%20swing%20(bottom%20right?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

WATFORD TOWN HALL, The Colosseum as it has been grandly renamed, sits opposite a paved-off high street an hour outside London. Adorning the outside walls are posters inviting you to bingo, a Moody Blues gig and a weekly ’70s disco. It’s the most unlikely setting for anything to do with Rings; Wellington feels like another world. Inside, composer Howard Shore and Jackson are working on the score for The Return Of The King, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra is poised — between union-prescribed tea breaks — to work its much

sought-after brand of magic.

“Town halls have a particular sound to them,” explains Shore, a student of acoustic physics. “There’s something resonant in the size and shape of these turn-of-the-century buildings — it was a way of creating a sound for Middle-earth away from the regular studios of Los Angeles and London.”

Hence this unlikely place has become the home for recording the trilogy. And, again, they are running mighty close to the wire. Live shooting finally finished in mid-October (for a series of effects shots of Orcs storming the gates of Minas Tirith — no cast required) — that must be some kind of record. Yet, rather than damage limitation, this is further evidence of the drive for perfection.

“More than the others, Peter is not going to let this one go easily,” confirms producer Barrie M. Osborne. “This is his favourite and he’s going to push it as hard as it can go.”

You can feel it here on the shop floor, as Shore pulls up a seemingly flawless passage of music: “That’s not an A on bar 13,” he instructs strings. They all lean forward to make a mark on their manuscripts. The music begins again, soaring to the rafters, conjuring the arcane grandeur of Middle-earth across the dance floor (no drinks permitted) of a drab town hall. It halts, Shore nods and dashes off to the sound booth to join Jackson at the monitor, synching the phrases and sweeps to the action on screen. “For a normal movie this takes three weeks,” an assistant marvels. “This has been going on for three and a half months. It’s that big, that important.”

Shore has been much more than a composer for hire — he has been a close collaborator joining the director on a three-year journey. Jackson was determined that the music would be as much a part of the narrative force as the words, that you could play the CDs back-to-back and trace the arc of the story, an operatic suite to rival the world of Wagner. “Music is so much a part of the story and the screenplay,” says Shore. “I’m a composer, but I’m a writer as well. I had to totally immerse myself in the mythology.”

Thus Shore has likened his own quest to that of Frodo, a struggle of epic proportions to complete his sonic saga. And the third film has presented its own thrills and challenges: “Shelob has her own compositional work, something unique for her. The Paths Of The Dead has this grand male chorus. Gondor has its own architecture compositionally… I also got to work with Annie Lennox.”

It transpires the androgynous former Eurythmics singer will be singing the haunting song that closes the movie and, finally, the trilogy. After years of dedication, obsession and undoubted joy, closure hangs tantalisingly in the air. The time has come to assess their achievement, both personal and cultural. Rings has changed Hollywood. Against a downshift in quality at the expense of, well, expense and the double-edged power of technology, these three films have tamed those two beasts and become a triumph of populism married to artistic integrity. Credit goes to New Line; as much as they have gained (hippest house in town these days), it was their adventurism that gave birth to greatness.

“It’s kind of shocking to think back,” laughs executive producer Mark Ordesky, who has represented the $310 million New Line invested in total. “Some studios didn’t even take the meeting with Peter. We’ve always been a very counterculture company. We made Pink Flamingos. We made The Lord Of The Rings. They both represent us.”

There’s one last thing. You can feel it hovering around the edges of every ounce of effort underpinning The Return Of The King. The box office will come — we’ve come this far, who doesn’t want to see it through? The point is Oscar. Will it? Can it? Surely it must? And if it doesn’t, will Christopher Lee make good on his promise and resign from the Academy?

Jackson’s triumph is indelible, but this is the final piece, the one thing to rule them all. Hollywood is all a-quiver with its own brand of anticipation — this time the recognition will come, it’s a shoo-in, the water-cooler sages have decreed it so. New Line want it bad, they are gearing up a huge push for success. Although Ordesky is sly enough to deflect the issue: “It’s not like we made these films with Oscar in mind. I mean, if these films had done half the business that they did we would be sitting here going, ‘What a huge success!’ And if we’d got no Oscar nominations, you’d still be saying, ‘Wow, you guys must be really happy.’ So, you know, we are really dealing with an upscale problem.”

That, though, is the price of perfection.