It's been 35 years since Martin Scorsese' Taxi Driver first crashed into cinemas. Thirty-five years that have eroded its bleak power and the potency of Robert De Niro's towering central performance not one iota. It's as stunning, bleak and demanding as it when it screened on those Hell's Kitchen, East Village and Queen's screens back in the chilly winter of 1976. As the seminal thriller returns to the cinemas this week, Empire takes a cab ride back to the '70s...

So said John Hinckley III, summing up his state of mind as he attempted to assassinate American President Ronald Reagan on March 30, 1981, in Washington D.C.. The film he walked into was Taxi Driver. Just as psycho-cabbie Travis Bickle tried to assassinate Presidential candidate Palantine in order to “save” underage hooker Iris (Jodie Foster), Hinckley, having watched Taxi Driver on a loop, tried to take out Reagan in order to “effect a mystical union” with the real Jodie Foster. As critic Amy Taubin and others have pointed out, it is particularly fitting that Hinckley’s assassination failed. Taxi Driver is marinated in the failures of its age: the failure of the US in the face of Vietnam, the failure of politics in the face of Watergate, the failure of the counterculture in the face of The Man, and the failure of masculinity in the face of feminism. And of course, in the face of such abject failure, Taxi Driver went on to become a lasting success, a vivid fever dream we still haven’t woke up from 34 years later.

"The film holds up because it was true"

Scorsese’s most enduring film is that rare flick: a product of its time that has managed to remain timeless, partly through the brilliant amplification of its universal theme – being lonely in a big city never goes out of fashion — partly through its unnerving ability to contain its own contradictions. It is at once realistic yet expressionistic, loosely structured yet tight as a drum, very American yet European, profane and violent yet spiritual, deeply serious yet hysterically funny. It also ends on an ambiguous note — Is it the dream of a dying man? A fantasy? A black-comedic grace note? — that makes Inception look cut and dried.

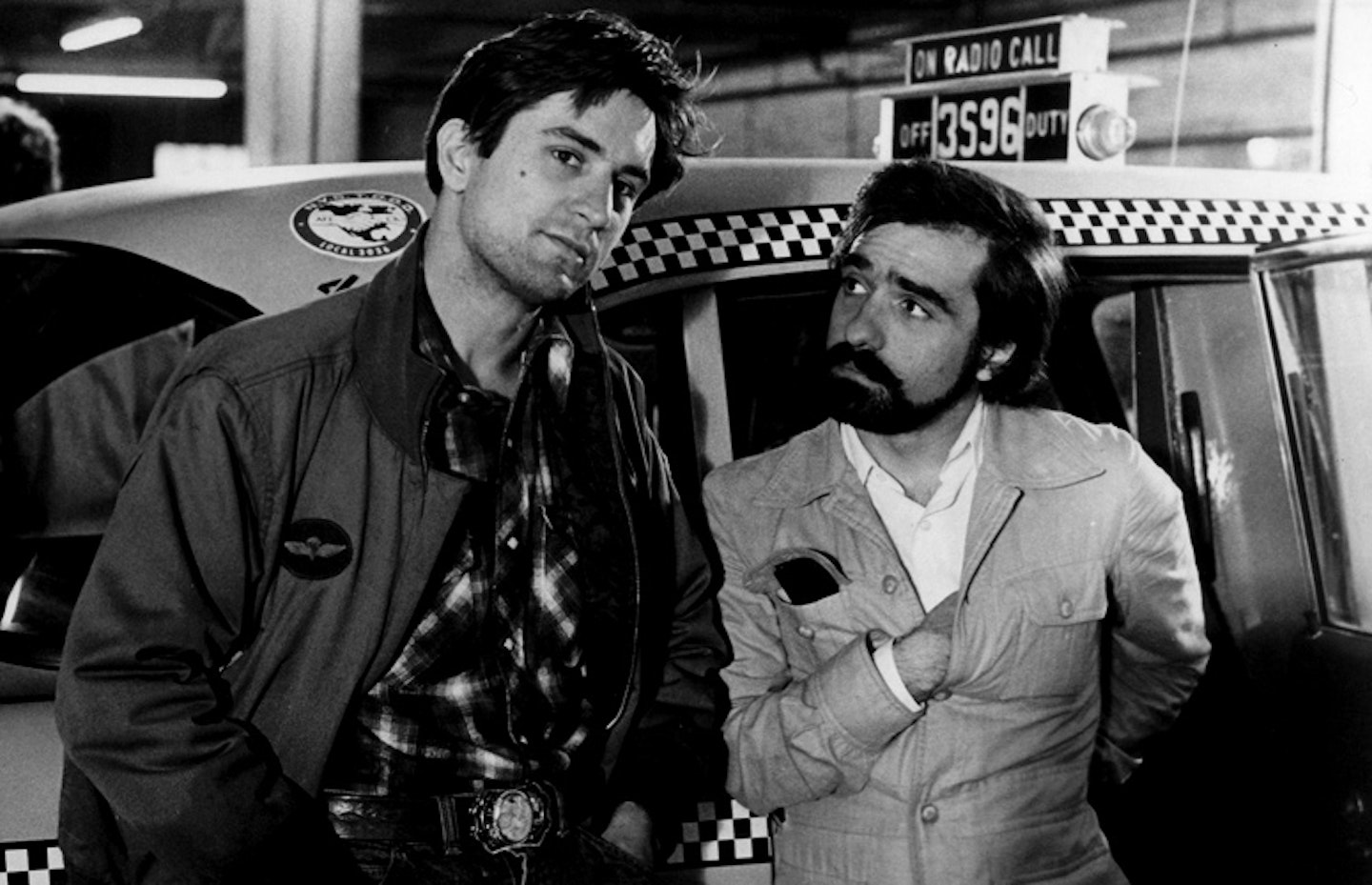

It’s long been the quick-and-easy conceptualisation to describe Taxi Driver as the product of an unholy trinity — one-third writer Paul Schrader, one-third director Martin Scorsese and one-third star Robert De Niro (or, if you’re a poor typist, Robert De Biro). While you can’t write off the efforts of key artisans — Michael Chapman’s hallucinatory cinematography, Marcia Lucas’ deft montages, Bernard Herrmann’s score, with its urban hymns to twisted romance and foreboding — so complete is the intersection between the central trio that collaboration and creativity blur at the edges. “The film holds up because it was true,” says Schrader. “Bob (De Niro) and I were in that place at that time.”

Notes from underground

That time for Schrader was early ’70s LA. Aged 26, he was a budding film critic who had just broken up with his wife, his mistress, and his mentor Pauline Kael; he was also deep in debt, living in his car, haunting porno theatres and drinking like a bastard. When he went to hospital complaining of stomach pains (an ulcer), he realised that the nurse was the first person he’d spoken to in weeks. Out of this malaise emerged Travis Bickle, a Vietnam vet who falls for a Madonna (Betsy, played by Cybill Shepherd) and tries to save a whore (Jodie Foster). With influences as diverse as gunman Arthur Bremer’s diary, Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground, the spiritually spare films of Robert Bresson and Harry Chapin’s song Taxi swimming round his head, Schrader knocked off multiple drafts in just two weeks. As such, Taxi Driver reeks of a feverish inception. The early drafts had Sport (Harvey Keitel’s pimp) as African-American and Travis only killing black people in the final reel until common sense prevailed — as it is, Taxi Driver is still a film about a racist that skirts dangerously close to racism. But if he nailed the psychosis of a lonely cabbie, Schrader failed miserably on New York’s street layout (this was in the days before Google Maps), Scorsese chiding the writer for his lack of geographical knowledge.

"Thank God for the rain"

Whether he knew his 1687 Broadway (where Travis calls Betsy) from his East 13th Street (where the final shooting takes place), Schrader’s screenplay is the kind of perfect script a writer delivers once in his life. Everything feels right, from the character names (Travis = travel, Bickle = pickle, a nifty distillation of the character), to the voiceover, to the neatness of the metaphor — cab drivers are seemingly surrounded by people all day but are, in the end, totally alone. Unlike most airy-fairy ’70s scripts, it is tautly constructed, each scene leading logically to the next, but still has time for superb comic vignettes, be it the weird ramblings of cabbie Wizard (beautifully built up by Peter Boyle), Albert Brooks’ emasculated campaign worker, or Travis’ run-in with a secret service agent. It is far funnier than any film that inspired a Presidential assassination attempt has the right to be.

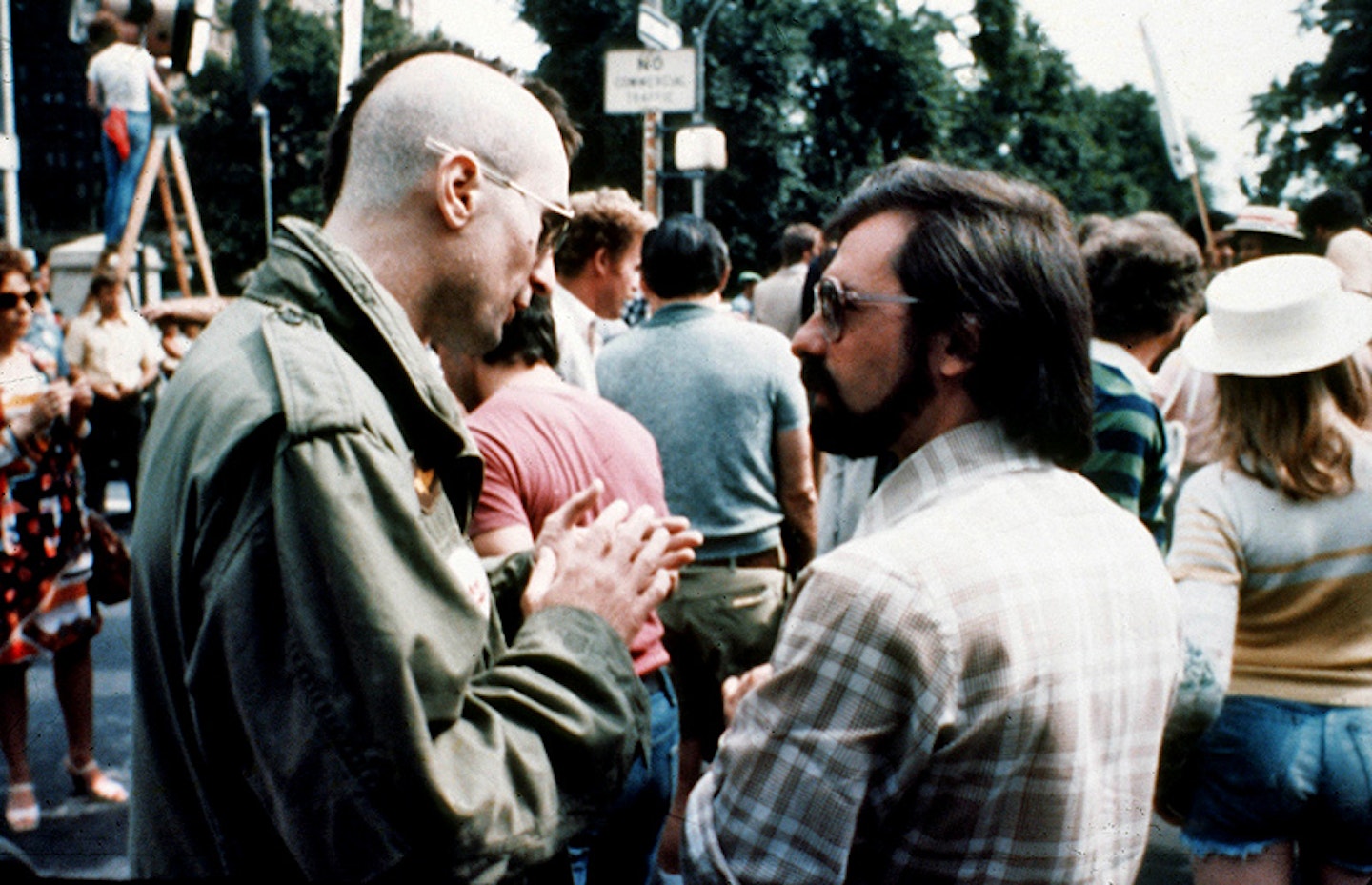

Hot off Mean Streets, Scorsese and De Niro came as a package, replacing Summer Of ’42 director Robert Mulligan and Jeff Bridges (his Travisness, or Traver, or El Traverino if you’re not into the whole brevity thing, don’t sound quite right for Bickle). This was Scorsese at the height of his Movie Bratness, shooting in a boiling hot New York during the summer of ’75, recutting the end with a just-finished-Jaws Steven Spielberg, his film fizzing with filmic references — The Searchers (the plot), Two Or Three Things I Know About Her (the Alka-Seltzer glass), The Wrong Man (Travis’ POV shots), A Bigger Splash (the framing), Murder By Contract (Travis exercising) and Salvatore Giuliano (the final crime scene) are just the tip of the iceberg.

Scorsese uses every weapon in his arsenal (jump cuts, arbitrary dissolves, lurid colours) to render Travis’ skewed point of view. Unlike most movies, where camera moves are functional (i. e. following a character), Taxi Driver’s camera moves are seemingly unmotivated, never allowing Bickle to settle in the centre of the frame, always insinuating tenuous psychological states. As Travis tries to persuade his dream girl Betsy to go on another date, the camera slowly drifts away from him, focusing down a long, empty corridor leading nowhere. If you want a moment to stand in for the whole of Taxi Driver, this is it — loneliness, emptiness and sickness in a single image.

God's lonely man

Flying back to New York while shooting Bertolucci’s 1900, De Niro learned how to drive a cab, tape-recorded soldiers from the Midwest to get the accent down, and dropped 35lbs for the role, but his commitment stopped short of the Mohawk, the actor instead sporting a bald cap. Astonishingly, De Niro creates a 3D character in ways Avatar can only dream of simply by gazing (in rear-view mirrors) or listening. For all his intensity, Bickle is surprisingly charming, especially during his wooing of Betsy. A De Niro character is at his best buying his girl a Kris Kristofferson album she already owns or taking her to a porn flick (Ur Kärlekens Språk) she would never see. You may hold Rocky And Bullwinkle, 15 Minutes, Machete and Meet The Parents VIII against him, but Travis Bickle gives De Niro a pass for life.

A Walking Contradiction

Considering it is, as Kris Kristofferson sings, “A Walking Contradiction”, Taxi Driver was well-received on its release, glowingly reviewed and the winner of the Palme D’Or. Tennessee Williams was the jury president (although he reputedly hated the violence). It lost the Oscar to Rocky, but compared to Scorsese’s more recent contenders, it is striking just how small, edgy and raw it feels. It’s a movie that has continued to fuel pop culture for decades. If De Niro had a dollar for every “Are you talkin’ to me?” riff, he could open a restaurant (hang on...). Scorsese and Schrader collaborated on a spiritual sequel, Bringing Out The Dead (with, sadly, Nicolas Cage replacing De Niro), and Schrader has played with different iterations on the ‘man in his room’ figure in his own screenplays, from American Gigolo through Light Sleeper to The Walker, in which the protagonist is gay. “I finally got Travis out of the closet,” quipped Schrader.

In a Faustian pact to get the difficult movie made, Scorsese and Schrader signed the rights to the character away, so there is nothing to stop Taxi Driver II: More Scum On The Streets — In 3D!, starring Ryan Phillippe, appearing soon. Perhaps less likely, Scorsese, De Niro and Lars von Trier announced a sequel at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, though nothing seems to be happening. In 2005, Majesco announced a video-game of the film, but thankfully nothing has come to light. When the time comes, when we’re sitting in our underpants scoring points for blowing away “whores, skunk pussies, buggers, queens, fairies, dopers, junkies”, we’ll know that cinema’s greatest loner has been fully assimilated into the mainstream. Long may he remain an outsider.