If Casino Royale was both a leap forward and a return to basics for James Bond, the near-universal love Daniel Craig’s debut received left an even bigger problem: how to follow it up. The answer came two years later in 2008’s Quantum Of Solace, directly continuing story threads from the previous film and pitching 007 into a tangled web of nefarious characters connected to Vesper Lynd’s death. But making a major blockbuster during the Writers’ Strike was no mean feat – and incoming filmmaker Marc Forster, more renowned for indie fare, had a lot to live up to. Read Empire’s original feature about a film that would become one of the most divisive entries in the Bond canon…

PREVIOUS: The Making Of Casino Royale

———

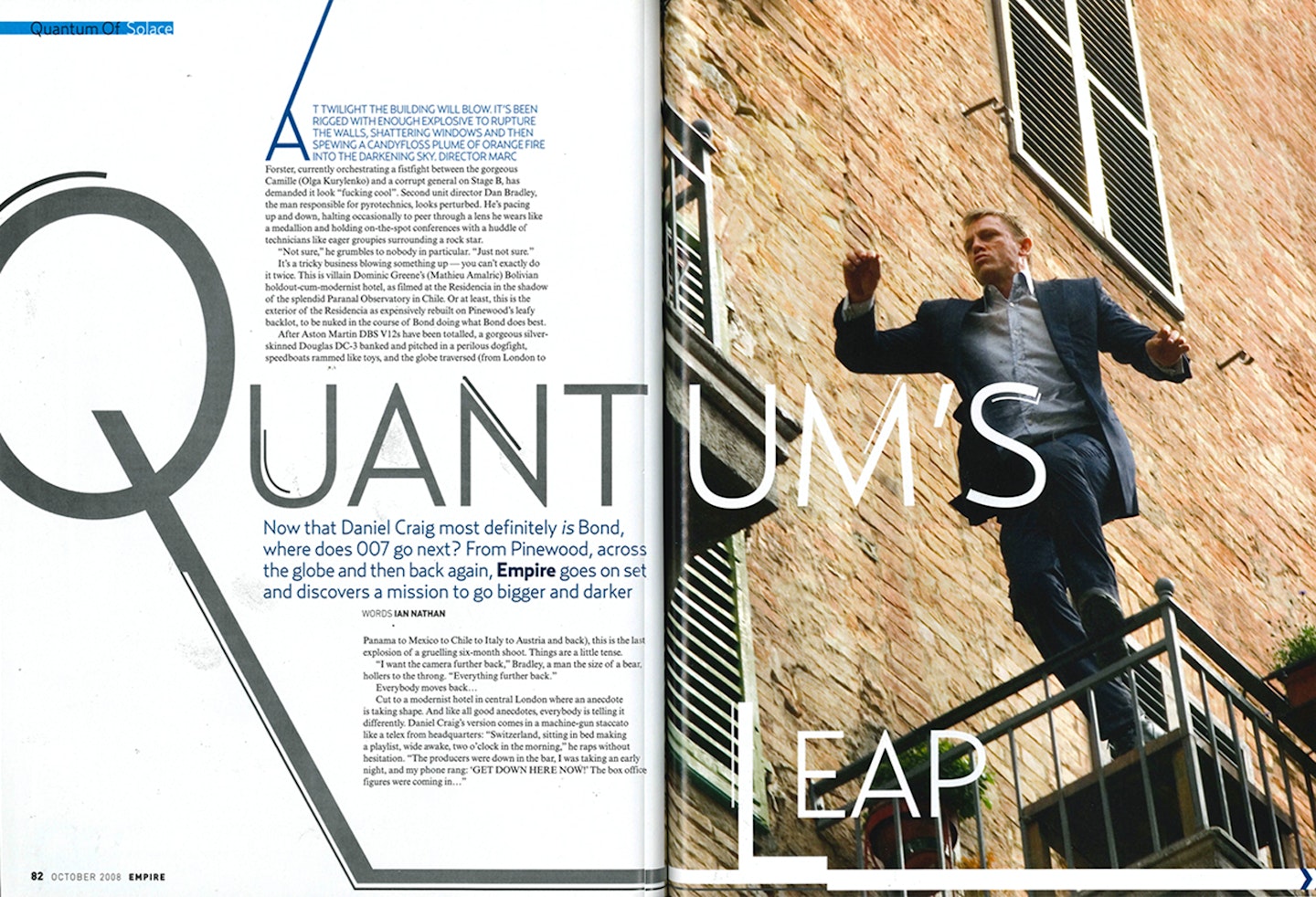

At twilight the building will blow. It’s been rigged with enough explosive to rupture the walls, shattering windows and then spewing a candyfloss plume of orange fire into the darkening sky. Director Marc Forster, currently orchestrating a fistfight between Camille (Olga Kurylenko) and a corrupt general on Stage B, has demanded it look "fucking cool". Second unit director Dan Bradley, the man responsible for pyrotechnics, looks perturbed. He's pacing up and down, halting occasionally to peer through a lens he wears like a medallion and holding on-the-spot conferences with a huddle of technicians like eager groupies surrounding a rock star.

"Not sure," he grumbles to nobody in particular. "Just not sure."

It's a tricky business blowing something up – you can't exactly do it twice. This is villain Dominic Greene's (Mathieu Amalric) Bolivian holdout-cum-modernist hotel, as filmed at the Residencia in the shadow of the splendid Paranal Observatory in Chile. Or at least, this is the exterior of the Residencia as expensively rebuilt on Pinewood's leafy backlot, to be nuked in the course of Bond doing what Bond does best.

After Aston Martin DBS V12s have been totalled, a gorgeous silver-skinned Douglas DC-3 banked and pitched in a perilous dogfight, speedboats rammed like toys, and the globe traversed (from London to Panama to Mexico to Chile to Italy to Austria and back), this is the last explosion of a gruelling six-month shoot. Things are a little tense. "I want the camera further back," Bradley, a man the size of a bear, hollers to the throng. "Everything further back."

Everybody moves back...

Cut to a modernist hotel in central London where an anecdote is taking shape. And like all good anecdotes, everybody is telling it differently. Daniel Craig's version comes in a machine-gun staccato like a telex from headquarters: "Switzerland, sitting in bed making a playlist, wide awake, two o'clock in the morning," he raps without hesitation. "The producers were down in the bar, I was taking an early night, and my phone rang: 'GET DOWN HERE NOW!' The box office figures were coming in..."

“That was when we were in Paris, right?” Barbara Broccoli asks her longtime producIng partner Michael G. Wilson, his authoritative nod ushering her on. "We were downstairs in the Bristol Hotel after the Paris premiere, the box office had just opened in the US. Then the figures came in. We just rang him, told him to get his bloody jeans on and get down here and enjoy this moment."

One can picture the clinking of flutes, the spilling of Dom Perignon, an understandable air of smugness. The rethink of the Bond franchise – grittier, grungier, dare-we-say Bournier (we'll get to that later), a wake-up call to those still smirking over Roger Moore's Farah pants – had been condemned before anyone had viewed a second. Now Casino Royale was basking in the best reviews the franchise had ever received, and an American opening weekend of $41 million. That berk behind craignotbond.com had gone to ground. It was the victory lap: Blofeld defeated, the world saved; Bond could kick back, take the girl in his arms and await Q's incoming entendre, job well done. Well, he could if they hadn't done away with all that.

"I knew that we had a good film," asserts Craig, so swiftly Bond incarnate. "But the idea that it would be a box-office success was such an anathema to me. I just had no benchmark. I couldn't imagine what that success meant. I still can't."

Casino Royale made over $593 million worldwide, and Craig was seriously talked-up as a potential Oscar nominee. That didn't happen to the other guys.

"We felt we had made the right moves, we felt secure," says Broccoli. "But it had been a rough ride for Daniel." She sighs, still angry despite everything.

Nursing their hangovers the next morning, breakfast must have been a muted affair. Something slowly but surely dawning on all of them. Bond had been left gun in hand, death in his cold, blue eyes, fully formed as 007, but the mission had just gotten tougher. Now they had to outwit their own success.

"It's fucked up, isn't it?" grins Craig.

Cue: an explosion ripping through the Buckinghamshire dusk, captured by a battalion of artfully positioned cameras. Cue: a song, silly and sexy, its lyrics hinting at both hero and villain. Cue: those whirligiging credits. Cue: Quantum Of Solace.

———

Barbara Broccoli, daughter of the legendary Cubby, likes to tell a story about her father. About this young director who nervously approached him at a party to say, "I really wanna direct a Bond movie." "Oh, you're far too inexperienced," replied the producer. Steven Spielberg turned away crestfallen. Some years later, Cubby Broccoli was so profoundly moved by Schindler's List that he sent a letter to Spielberg in praise of what he considered a masterpiece. Spielberg wrote back: "Well, can I now direct a Bond movie?" "I'm not sure how serious he was," giggles Barbara Broccoli.

The offices of Eon, the production company created by Cubby and his partner Harry Saltzman in 1961 to make Dr. No, are to be found in Piccadilly rather than Whitehall, but you can't help thinking of M's office, and Bernard Lee's irritable voice crackling through the intercom to intercept Bond 's furtive flirtation with Miss Moneypenny. Acres of softened leather, wood panelling and the whispery hush of a library complete an old-school fustiness, a secret HQ in which British gents serve Queen and Country. That is except for the occasional framed poster for Thunderball’s Italian release or Goldfinger’s Japanese debut.

In these lavish rooms, Broccoli and Wilson, keepers of the 007 flame, hold court. It is the creative hub of the Bond industry, where all day long these two, with the aid of some great writers and brilliant directors – and some not so brilliant ones – plus six 007s, dream up adventures for the world's most celebrated spy..

"There was a sense that Casino Royale left Bond hanging in a really dark place," says Wilson. "We needed to get past that."

With the conga for Casino Royale eventually running out of puff, the pressure was on to capitalise on that momentum, to get a new script rolling. With a secret overarching story potentially traversing Craig's entire tenure as Bond – a SPECTRE-like syndicate of global troublemakers dropping off a baddie per film – the two producers had plenty of ideas. Broccoli keeps a file of cuttings from the Sunday newspapers she religiously pours over; Wilson brings a background of science and engineering, an insistence on logic. "He'll shoot things down,” laughs his partner. '''That would never happen, not even in a Bond movie.’”

Especially not within Bond's salty reinvention, predicated on not having invisible cars. Die Another Day had left them feeling trapped inside a formula. It was also very much still a winning formula (Die Another Day made $432 million worldwide), so it was with some trepidation they mentioned to distributor Sony they were throwing out the bath water and recasting the baby with an intense, blond-topped theatrical type. "We were so lucky with Amy Pascal (the head of Sony Pictures), she's the most supportive person," says Broccoli. "I think it is something to do with being a woman – it is all about making it work. "

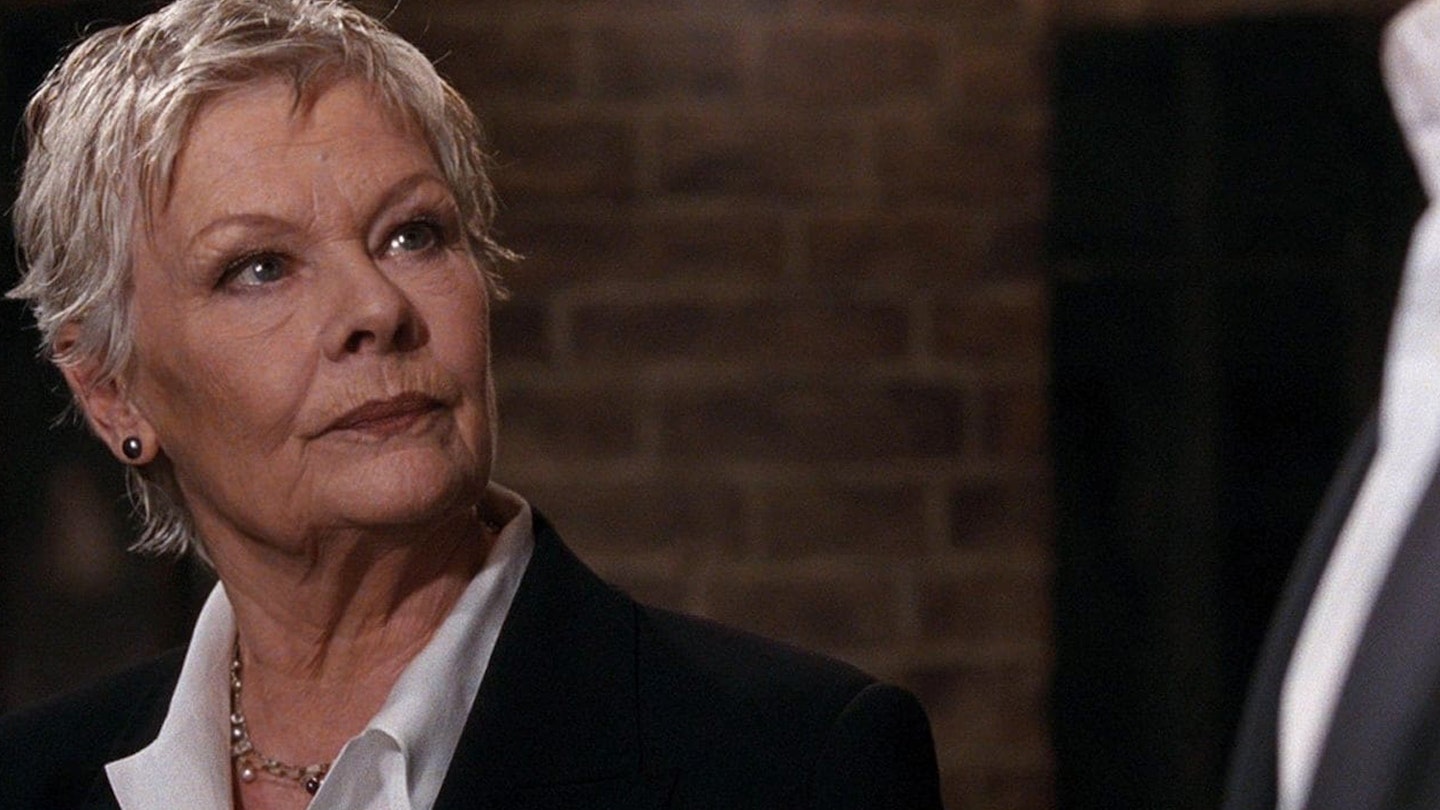

It's hard not to give Pascal the no-shit perspicacity of Judi Dench's M as the scene unfolds:

"Okay, what do you want?" asked Pascal.

"Well, we want to go back – to the original book," replied Broccoli.

"But isn't that like a card game? And doesn't the girl die at the end?"

"That's right."

"But we'll have fun because you'll have Q, you'll have Miss Moneypenny..."

"No, we won't. And we won't have Pierce. And we want to shoot the opening in black and white..."

"It was almost like one of those Orange commercials," laughs Broccoli.

Pascal trusted them, and they answered that trust. So, when it came to the sequel – and Quantum Of Solace should be regarded as a direct sequel rather than a new episode – they were emboldened. "She understood the pressure of making a film as good, if not better, than the last one,” says Broccoli. Quantum Of Solace’s budget has been estimated north of $200 million, although no-one's telling.

There had been rumours – typically internet-fuelled – that after Casino Royale’s back-to-Fleming approach, they would start the task of remaking the books in succession, as flinty and worldly as the author imagined them: Live And Let Die, Moonraker, Diamonds Are Forever et al. Wilson waves it away: "We don't want to repeat ourselves. Those pictures were fantastic pictures – what is the point of remaking them?"

Conceptualising Bond movies may sound like the perfect job, but crafting a coherent script for one is, according to Craig, "a fucking nightmare". With the origin story dealt with, the challenge now was to invigorate the standard protocol: that formulaic whoosh from pre-credit impact to the bad guy's lair going up in flames.

"They are always nervous about showing me the script," laughs Craig, who admits that he "sticks my oar in" from the start. "I'm like, 'Just give me the fucking script. What am I going to do, say no?'"

The title Quantum Of Solace (a perplexing monicker to further test Sony's equanimity) refers to a rather good lan Fleming short story in which Bond is told an anecdote over dinner in Jamaica. It is a bitter tale of a relationship collapsing into cruelty because the couple couldn't find the necessary "quantum of solace". The required peace of mind. The film has purloined the name alone (from a need-to-know file of potential titles kept at Eon), but there is something more to it.

The emotional journey is set. This organisation is responsible for killing the love of his life. There's vengeance in mind.

Bond, bereaved of his true love (Eva Green's Vesper Lynd) is caught between his duty and vengeance, but deeper than that he is a man, a spy, in search of his own quantum of solace; arguably the theme of all Bond films. "The emotional journey is set," explains Craig. "This organisation is responsible for killing the love of his life. There's vengeance in mind, there are other things too... Which we discover as we go."

Who would have thought, back in '62 amongst Dr. No’s sunny sprawl, that we would ever be talking about Bond going on an emotional journey?

"It's great, isn't it?" smiles Craig. "It's about putting some reality into the situation. I think it's more interesting if you watch people on screen and you go with them emotionally, feel what they're feeling... Although, at certain stages, this is about being James Bond and catching the bad guys."

First though, Eon had to catch a director. Who knows what list of potential helmers lies in the vaults of the ornate offices. But after Martin Campbell declined to return again, the search was on for a director to pick up the gauntlet left so tantalisingly on the shore of an Italian lake. Spielberg was now perhaps beyond reach, and would adhere to that top-heavy ruling that no filmmaker can outshine 007, but with the creative demands ramped up, there was no going back to makeweights like Roger Spottiswoode or Lee Tamahori. They needed a class act, minus the celebrity baggage.

"I said 'no'," laughs Forster, a tall, handsome man with a clean, bald Blofeld head, currently commanding an army of editors in his London offices. "I really didn't see any upsides. I was at a place in my career that I felt, within the $20-$40 million range, I could do any film I wanted and with complete creative control."

Why disrupt the flow? The German-born director had gained Oscar attention and fine notices for the likes of Monster's Ball and Finding Neverland; not a CV exactly brimming with car chases. Forster had no investment in the legacy, either. In fact, he proudly admitted to growing up without a television.

"There was no upside until I met Daniel," he confesses, "I really connected with him. Then I read this quote from Orson Welles that his biggest regret was never making a commercial movie."

Forster had circled Hancock and one of the Harry Potters (he can't remember which), but the exploration of the inner-Bond caught him like a tractor beam. “I wanted to do deeper,” he says greedily.

The pernickety director wasn't messing, either, demanding a complete rewrite of the first draft (by regular duo Neal Purvis and Robert Wade) from Paul Haggis, who had stoked the emotional boiler on Casino Royale. He liked what he got, as did Craig, but where Haggis had the film conclude in a flurry of snow – harkening to the alpine cool of On Her Majesty's Secret Service – Forster pictured Bond against a desert. "I had these visual components, all these different locations," he explains. Alongside intricate storyboards, Forster creates 'texture sheets' of images to evoke his visual ideas. "In the desert, it's unforgiving. You're out there and you might die."

Forster's template is a daring fusion of a modern world of shape-shifting governments and corporate wickedness (the villainous Greene is a blustering businessman fronting eco-themed hotels, with an eye on a mysterious resource beneath the desert) with a Connery-era lacquer of '60s glamour. There is a more traditional globetrotting gleam to Quantum Of Solace, but we're talking From Russia With Love rather than Octopussy.

"It's a really intense collaboration," says Forster. "Daniel on character, Dan Bradley on action, and Barbara and Michael on overall structure and story. And Judi brings that whole weird mother-son thing."

Although it wasn't until a flight, low over the Dosso de Roveri cliffs in Northern Italy, scanning for terrain to launch the film's opening salvo, that he finally realised what he was doing. "God, I was making a Bond movie," he laughs. "Had I actually said 'yes'?"

———

According to who you ask, Quantum Of Solace begins two minutes (Broccoli), five minutes (Wilson), 20 minutes (Forster), or one hour (Craig) after the final shot of Casino Royale. In short, with barely time to catch breath, we are pitched headlong into the action: Jesper Christensen's Mr. White writhing on the ground in agony, having presently been knee-capped by a vengeful 007. White is a potential connection to that elusive super-organisation (could it be known as 'QUANTUM'?), as is the slimeball tycoon Dominic Greene. A car chase ensues, one currently being staged by Dan Bradley, the man who put the grunt into Jason Bourne's life.

"Images of his stayed with me: the milk truck crashing in Three Kings, the car accident in Adaptation,” recalls Forster. "Not to forget the Bourne stuff for a second. Car chases in particular are his speciality."

Tracing the rim of Lake Garda in Northern Italy is a perilous road entrapped by hairpin bends, narrow defiles and blindspots, regularly boring through the mountain flanks in long, dark tunnels. It is here that the second-unit, led by the redoubtable Bradley and Gary Powell – a wonderfully earthy stunt-master who visited the set of The Spy Who Loved Me as a boy ("My dad was a stuntman," Powell enthuses. "Showed me the bloody submarines!") – have been chucking Aston Martins, Alfa Romeos and heavy trucks around at irresponsible speeds. It's a breathtaking sight, the primacy of the Bondian art – perfect engineering, sleek as a fish, absolutely riddled with machine-gun fire and pulverised against bare rock.

"From the very beginning, audiences are going to know this is a Bond movie," delights Craig, clear that no matter how much talk there is of inner-turmoil, there's plenty of exterior-turmoil too. "Gary's theory is, 'If you don't do it, you won't feel it.'" Whatever the fakery of the actual shot, at some point Powell has had him handling the cars, mastering the boats. "When you know how it feels to drive a boat one-handed, you can recreate it," says Craig.

While in Haiti (shot in Panama) following a lead, 007 meets not only the smouldering and extremely dangerous Camille, but ends up in a furious boat chase. Cue: leaping out of the surf at full throttle, dodging oncoming cargo ships, getting strafed with bullets and forcing your companion to hold the wheel as you return fire. "But it's important you also feel the vulnerability," insists Craig. "It's like what Harrison Ford does so brilliantly – you're not sure he's going to get it right."

Comparisons with Bourne tend to generate a livelier response. It is true that the Bourne trilogy redefined the spy movie aesthetic as a telling mix of brute force and emotional resonance, and Casino Royale followed suit. But Bourne was created as a stark, modernist reflection of Bond to begin with, despite the cynical views of Paul Greengrass: "Bond loves being a secret agent – he's a cruel character, an imperialist. Bourne is the reverse. He's filled with doubt and anxiety."

"I don't think it's like Bourne at all," starts Craig. "Dan is here to do exactly what he's good at doing. He's just come off Indiana Jones – are we going to be more like Indiana Jones? We're applying Dan's talents to this movie. Sorry to be political about it, but I'm certainly not going to get into a pissing competition with the Bourne fans."

If the shit hits the fan like goose-stepping Nazi bastards, you hope the civil service will go, 'We've got it covered.' That's Bond.

The shoot has also, very publicly, been hit by a series of accidents, such that it ended up being dubbed "Calamity James" in the London press. Here in Garda alone, two stuntmen were injured in a car crash when a release charge didn't fire correctly, sending a remote-controlled Alfa Romeo cartwheeling into a piloted one. The stunt drivers' car was left dangling, Italian Job-style, over a 50-foot drop. During a simple drop-off, a driver lost control of a DBS, skidding on the wet Tarmac and plummeting a £135,000 automobile into the lake. The driver, Fraser Dunn, claims to have come round at the bottom of the Iake, narrowly escaping through a broken window. "I wasn't going that fast," he implored.

Such calamity is arguably testament to what Powell describes as a "back-to-basics", CG-averse approach to action. "It about realism," he says. "You don't get the stuff without taking risks. "

———

Daniel Craig likes to tell a story about his watch. It’s a Rolex Submariner 6358, an exact replica of the one he remembers Sean Connery wearing in Goldfinger.

The story goes that the budget on Dr. No didn't run to a Rolex, and Cubby Broccoli, aghast at Connery's naked wrist, simply slipped off his own and handed it over. That watch stayed there for five films. The point, for both Broccoli and now Craig, is that it was lan Fleming who first put a Rolex on Bond's wrist. "He could not just wear a watch, it had to be a Rolex," is the line in Casino Royale (the novel), that hymn to fetishism. Fleming, above all, remains the lynchpin.

"It's Fleming's turmoil that always comes across," enthuses Craig, who adores the muscularity of the books. "He hates Bond at times, wants to fucking kill him. I've tried to make sure we pick up on that turmoil."

We're sitting in the piercing light of the Atacama Desert in northern Chile, on the roof on the real Residencia, the view a moonscape of pale rock all the way to the sky. It is here the film will explosively conclude. Where Bond and Camille will confront both Greene and their mutual destinies. Olga Kurylenko has been dropping vertically between balconies, and will end up kicking an evil general in the nuts. Craig is about to blast through a skylight and leap down onto the fleeing Amalric as Greene. The moment is pure action, but also captures Bond's inner-conflict – he could choose to kill his foe in cold blood, enact vengeance, or stick to duty and bring him to book...

Bond tends to get slagged off by high-minded types, sneering, like Greengrass, at his imperialist impudence, or smirking like Anthony Lane, critic of The New Yorker, at the "zero gravity" of Moonraker. They may have a point, but it feels like an old argument. Casino Royale and now Quantum Of Solace have returned us to the fascinating murk of Fleming's mind, Bond as a contradictory force: ruthless, unfeeling killer and British gent. The pliable tease that, in order to save the world, it is an innate sense of British civility that is required.

"This stuff is actually quite important to me," continues Craig, warming to the subject. "You have the monarchy, you have government, then you have the civil service. The reason the civil service remains a non-political organisation is that if the shit hits the fan like goose-stepping Nazi bastards, you hope the civil service will turn around and go, 'We've got it covered.’ That's Bond.”

Bond may do things that are morally questionable, but he also does them for the greater good, You can have confidence in his moral barometer. "He has integrity," determines the actor. "It makes it possible to be who he is.”

There are no actual rules when it comes to making a Bond movie, just principals. Barbara Broccoli and Wilson never like to hem a director in with directives, but there is something on which they will not budge. "He's not corrupt," demands Broccoli, her eyes flaring passionately. “It's there in (Fleming's Soviet counter-intelligence unit) SMERSH's file on Bond – he won't take bribes, he's incorruptible. His Britishness is part of that. That aura."

So, as long as he stays true to Queen and Country, could we end up clambering even deeper into Bond's increasingly tortured soul?

"We make family adventure films,” says Broccoli, backing off, "but there is something bitter and twisted there. What is it Pauline Kael said? 'Sadism for the entire family…’ We wouldn't want to make an art film.”

"They are family traditions," says Wilson, the more conservative of the two. "Fathers taking their son, first dates, things like that. We always need to bear in mind that it is a family tradition.”

Craig allows himself a rare, boyish grin. "You know," he says, "It's just a fucking Bond movie.”

James Bond will return…

Originally published in the October 2008 issue of Empire Magazine.

NEXT: The Making Of Skyfall

READ MORE: Who Will Be The Next James Bond?