Between 1987 and 1997, Paul Verhoeven made three of Hollywood's most violent, subversive sci-fis. Empire revisits Robocop, Total Recall and Starship Troopers with the outspoken director.

This article first ran in Empire issue #278, published in August, 2012. Subscribe today{

Sometime during the mid-1980s, Dutch television aired a somewhat sombre documentary entitled The History Of Dutch Film. In the fifth episode of this worthy endeavour, optimistically called Tomorrow It Will Be Better, the cameras followed the then-most successful Dutch director in history to the airport. "The director who has lured the largest number of people into the cinema leaves for Hollywood," the voiceover intones. Verhoeven, a satchel round his shoulders, glares unhappily at the camera. The voiceover is not quite telling the truth. He is not so much leaving as being run out of town. All that are missing are the country's film critics and massed industry mavens. Clutching burning torches. Willing his downfall.

By the mid-'80s, Paul Verhoeven had pissed off pretty much the whole of the Dutch film industry. Though by then one of Holland's most successful filmmakers (his Rutger Hauer-starring love story Turkish Delight had won him an Oscar for Best Foreign Language film in 1973), his dedication to commercial success via appealing stories and a strong slug of sensationalism had reached its zenith with Spetters, which might very loosely be translated as "Dudes", in 1980. This explicit tale of a trio of motocross buddies who fall in love with the same girl, which featured among other controversial scenes a gay gang rape, had really put the Dutch establishment's back up. Which wouldn't have mattered, apart from the inconvenient fact that they wrote the cheques.

"Of course Spetters was a successful movie," laughs Paul Verhoeven, now 73, sitting in the kitchen of his home in the Netherlands (he now divides his time between Holland and Los Angeles). "In the United States, of course, that would translate into you getting more freedom, but in Holland, it meant you got less. People who were basically jealous tried to sabotage me. Movies in Holland normally are 40 or 60 per cent subsidised by the government. By the mid-'80s I felt that it was nearly impossible for me to get money from these very left-wing committees. Everybody saw my movies as very superficial and commercial and showing bad things and all that stuff. They felt that I was degrading the cinema and degrading the whole of society, especially in Spetters."

So, aged 46, Verhoeven came to the disturbing conclusion that if he didn't do something drastic, his career as a film director was as good as over. There had been offers from America before. After Turkish Delight won the Oscar, even Steven Spielberg had called and extended a personal invitation. But Verhoeven dithered. His English was passable but not strong, he had assembled a troupe of actors and a crew in Holland that he trusted and enjoyed working with, but more importantly, he had a wife and family to consider. "In fact, it was my wife who convinced me to abandon Holland and to go to the United States and see how it would go there," he says a quarter of a century after making that fateful choice. "I would not have even dared to do so without her support. She said, 'You go and I will follow later after the kids have finished school, but I don't want you to be further humiliated. And there are so many possibilities in the United States, so just go.'"

So like generations of persecuted directors before him - the Billy Wilders and Fritz Langs - he packed up his bags and emigrated to the land of filmmaking opportunity. He abandoned a society and industry terrified of being degraded and defiled by his ferocious imagination, and headed off for one that didn't seem to mind being degraded and defiled one little bit. And he had a secret weapon: a screenplay in his back pocket. A screenplay about the future of law enforcement. A screenplay entitled RoboCop.

RoboCop

Coincidentally, we have Mrs. Verhoeven to thank for that, too. Among the steady stream of scripts that had been heading across the Atlantic since the international success of his Turkish Delight was one by relative newcomers Ed Neumeier and Michael Miner. RoboCop had had its genesis when Neumeier, doing some low-level chores for a new film called Blade Runner, asked a crew member what it was about. '"It's a film about a cop who hunts down robots," came the reply. Possibly a goer, thought Neumeier, but isn't the reverse just as good an idea? A robot cop who chases down human villains? The result was RoboCop, a tightly wound, shamelessly violent futuristic thriller, but one that had at its heart a surprising streak of melodrama as well as a deftly buried black sense of humour.

"I remember very well. I was at the beach in the South of France on holiday and I got it there. I skim-read it and just threw it away. I thought it was terrible," Verhoeven smiles. "I thought it was completely ridiculous." The unimpressed auteur headed off for a dip and when he came back found his wife poring over the offending script. "I came back and pretty much said, 'Well, that's a piece of shit,' and she said, 'I think you're wrong. Read it again because there are many possibilities here for you to do something different and interesting.' And so then I decided to read it again more carefully."

This was not quite as straightforward as it sounds. Though Verhoeven's English was better by orders of magnitude than almost anybody in Hollywood's Dutch, it was still something of a slog. "I had to have a dictionary next to me because there were so many words that I didn't understand, so it was very slow going," he remembers. "But ultimately I saw what she had seen and what she thought that I had the ability to do, half-action, almost half-comedy with it. And so I decided to make a call to (Orion Pictures' chief) Mike Medavoy and I said, 'I'm in Canada to do one of the Hitchhiker TV episodes and I'll come through Los Angeles and we'll talk about RoboCop because I might actually want to do it.'"

Arriving without the support of his family in Hollywood in 1986, Verhoeven found himself alone in his Beverly Hills hotel room disconcerted by the kind of cultureshock that hits many a European when they make the trip to the West Coast. "At that time when you put on the television, especially on Sundays, there would be all these Christian preachers," he says, recalling his bewilderment. "And the incredible commercials - this was certainly not prevalent in Holland or even in Europe at the time. It was really strange to me," he remembers. He watched, amazed, as the Challenger space shuttle disaster played out live on his TV set, only to be interrupted every ten minutes by garish ads by used-car salesmen. But rather than let the sensation of being a stranger in a strange land overwhelm him, he decided to turn it to his advantage. The oddness of America would become one of the subjects of the film.

"I used my amazement about the United States in the movie. This incredible sense of astonishment that I had. This was much more so than with Total Recall or Starship Troopers, where I was not so amazed, because by then had lived in America for some time and was more analytical and critical." The result would be a film threaded through with darkly satirical elements - including the faux TV commercials that would attract so much attention ("Nukem! Get them before they get you! Another quality home game from Butler Brothers") - elements that were present in the original screenplay but which appealed immediately to Verhoeven's persistent feeling of being an outsider, and which he emphasised.

The shoot itself was a tense affair that more than occasionally featured spectacular temper tantrums. Verhoeven had cast the deeply Method-committed Peter Weller in the role of Murphy / RoboCop. "Orion (who had distributed the previous year's massively successful The Terminator) felt that the actor should be Arnold (Schwarzenegger) again. But the argument against was that Arnold was already so enormous that putting a suit around him would bring the whole thing out of balance. So we went with Peter Weller based really on the fact that his chin was very good."

Weller's commitment to the Method (much to Verhoeven's bafflement, he refused to respond to his name but only to Murphy or 'Robo'), together with endless delays in the delivery of the RoboSuit, designed by Rob Bottin (who at one point during a particularly fiery discussion became convinced that he might actually wind up exchanging blows with his director), resulted in the pair finding themselves almost permanently at loggerheads. Bottin's original design had been jettisoned at the last minute to be replaced with a second version, based upon designs rooted out of a Japanese comic book, which was itself then rejected and the original reinstated. The result was that when the suit finally arrived on location in Texas, where the film had been shooting for two full weeks, Weller had no time to rehearse in it. Within a few hours the screaming matches had become so intense that producer Mike Medavoy flew to Dallas and shut the production down for two days. Weller, by now completely uncooperative, was summarily fired.

"This was really my and Ed Neumeier's fault," admits Verhoeven. "We had caused the delay and when the costume came he had no idea how to behave in that suit. He had been training with a lot of American football equipment on to feel the difficulty, and he was working with a pantomime guy. But all that was fruitless when he had to put on the costume because it was so inhibiting. We got into a terrible situation where Peter felt that he looked like an idiot in the costume because he could not move and that became a big deal. Medavoy decided that we needed to cool off."

In fact, Weller's firing had been more a show of power than a real canning. After all, the $600,000 suit had been built especially for him and finding an actor who could fit it at short notice would have been a virtual impossibility. As Verhoeven biographer Rob van Scheers reports, when news of the contretemps spread, there was a flurry as agents in Hollywood hustled to find a replacement actor. Ed Neumeier pointed out that they were actually looking for any guy with the same shoe size.

"Finally we talked to Peter and we made everything clear for him and he tried again and two days later we could start," says Verhoeven. "But that was a very dangerous period because it looked like the movie might fall apart. It was because of our stupidity the costume was so late. But yes, there was certainly a time when I really wanted him to walk off the movie."

When RoboCop was released in 1987, it was an instant hit both with audiences, and perhaps surprisingly but certainly gratifyingly for Verhoeven, with the majority of critics, who spotted under its teenager-pleasing ultra-violence the sly satire and irony that had attracted the Dutchman to the screenplay in the first place. Though this was not universally understood. "The critic of the Los Angeles Times I think was watching it and some commercial comes on, and that critic walked out to the projectionist and told him, 'You've put on the wrong reels,'" says Verhoeven. "I mean, that really happened. The whole style of these intermezzos of news in the middle of an action movie I think was almost unheard of at the time. Although actually he should have known, because Citizen Kane does some of the same stuff."

But never mind. The movie was a hit. Back in Holland, the 'For Sale' signs went up chez Verhoeven. His great gamble had paid off. And across town, another European immigrant with a thick accent and boundless Hollywood ambition watched the director's American debut with more than a passing interest.

Total Recall

After the stunning success of RoboCop, Verhoeven dived into preparation for his second Hollywood outing, which was all set to be a big-budget star vehicle. But this one was not to be. "I was meant to do Black Rain with Michael Douglas," he remembers. "But it was not so fast to set up and it took some time. And so Arnold pushed (Carolco co-chief exec) Mario Kassar to give me the job to direct Total Recall. I really did this movie only because of Arnold."

Total Recall, adapted from Philip K. Dick's 1966 short story We Can Remember It For You Wholesale, had been languishing in development hell for well over a decade. The story had been optioned by writer/producer Ron Shusett for a mere $1,000 in 1974, but he and co-writer Dan O'Bannon struggled to wrestle a workable screenplay out of the slender tale of a man who buys a memory implant of a Martian holiday only to find it reawakening apparently real memories of his time as a Martian undercover operative. Directors including Fred Schepisi, Russell Mulcahy and Lewis Teague had been attached and then unattached from the project while O'Bannon and Shusett hammered out draft after draft. David Cronenberg worked on it for almost a year without success. (Famously, when he saw Cronenberg's version of the screenplay Ron Shusett angrily declared, "You know what you've done? You've done the Philip K. Dick version!" Cronenberg replied that he thought that was the point of the exercise. "No! We want to do Raiders Of The Lost Ark Go To Mars!" Shortly afterwards Cronenberg departed and Shusett gave up on the project altogether, he and O'Bannon starting work on a little project called Star Beast...)

Thus when Verhoeven was told by Kassar that the screenplay was on its way round to his house, he expected a postman with a thick envelope. Instead a delivery van appeared and deposited no fewer than 45 full drafts on the alarmed director's doorstep. With the 20-page short story in one hand and the 5,000 pages of aborted screenplay in the other, Verhoeven pondered how to wrestle the behemoth into a shootable script. He found the solution to his conundrum in his lead actor.

Having essentially been given the job by Schwarzenegger, Verhoeven was under no illusions that this was to be a star vehicle for the Austrian Oak, who was then reaching the lower slopes of his accelerating ascent to megastardom. The T-800 had instantly become an American icon, as to a lesser extent had Conan The Barbarian. But he had also shown a surprising facility for light comedy in Twins, something that Verhoeven noted with interest. Just as Verhoeven had taken his surprise at American culture and woven it into the fabric of RoboCop, he took the outlandish, bigger-than-life presence of his new star and built the whole movie around it.

"The fact that Arnold was there in fact made me decide to make the movie much lighter than it was originally conceived," he remembers. "I felt with Arnold everything was already quite hyperbolic just because of his presence. I felt that if I took the film too seriously it would fall apart. It needed a light touch, a certain amount of playfulness was required. I changed it in that direction so that it would not be too heavy-handed, which it could have been very easily. It needed to be light and funny and kind of over-the-top. Everything should be pushed a bit. So for example, when Arnold goes to the recall company, the guy that sells him the ticket is basically a car salesman. So I portrayed him like a car salesman."

Verhoeven commissioned yet another screenplay, this time from Gary Goldman, co-writer of John Carpenter's Big Trouble In Little China, and retooled the story, both playing up the futuristic gimmickry - "We put in the nails that change colour and the walls that are TV screens," says Verhoeven - and emphasising the element of the story that Verhoeven felt was most intriguing: the porous nature of reality and fantasy. Is everything that happens actually just an implanted memory in Douglas Quaid's head?

Shooting took place in Mexico City and, though not quite as incendiary an experience as RoboCop's had been, was still something of a trial for all concerned. With a budget of $55 million, Total Recall was then the most expensive movie ever made, and if that weren't enough pressure, the local bacteria were having a field day with Verhoeven and his crew. "It was very, very difficult. Mostly for health reasons," he winces today. "About ten per cent of the crew were sick at any one time from food poisoning. Horrible diarrhoea, stomach cramps. I was sick all the time, but I never stopped shooting. We were not immune to all the bacteria that Mexican people of course have no problem at all with."

Verhoeven fell ill near the start of the shoot and was rarely wholly fit. At one point, informed that Carolco was not covered by insurance for the first three days of his being hospitalised, and that it would deduct $150,000 from the budget for every day he called in sick, he directed from a stretcher on top of a minivan, attached occasionally to a drip. Unable to stand and ashen-faced, he informed the crew that unless a doctor actually said that he was dying, they were going to shoot. And when he did get his energy back, the stress of the schedule did little to assuage his famous temper.

"I still had to learn to cool down a bit. I learned there that things that would be normal on a Dutch set where you are screaming if something is not in order didn't work so well in the United States. So I had to abandon that technique," he smiles ruefully. "I had to learn and apologise a lot. But I'm okay with apologising and so it worked out."

If RoboCop had its staccato violent beats, Total Recall took Verhoeven's symphonic mayhem to new levels. "I had to look at the Blu-ray version recently, and I was amazed how violent it was," grins Verhoeven. "I looked and went, 'My God! This is ultra-violence!' There's cutting off arms and so on. There's a lot of blood and death. But I thought it was funny. That scene on the escalator, I had to tone it down because we couldn't get it through the ratings board, but [Schwarzenegger] uses a man as a shield. That was I think much worse when we shot it than what you see now. I always was having trouble with the MPAA. The censors do not understand, though, that when you cut, it actually becomes more violent. When you cut it down it loses the over-the-topness and the comic-book element. If you shorten it, it becomes more realistic."

Starship Troopers

On its publication in 1959, Robert A. Heinlein's Starship Troopers had caused the kind of controversy that rarely attends the publication of a science-fiction novel, and if it was completely faithful in few other ways, Paul Verhoeven's 1997 adaptation aped it in that. Heinlein's book, written apparently in a fit of pique after he had come across a campaign against US nuclear weapon testing in 1958, is in essence a series of stern lectures on the subject of the value of military service and citizenship (it apparently is said to remain on the US Marines' official reading list). A little of its queasy blend of machismo and romanticism can be gleaned from its dedication: "To drill sergeants everywhere who have laboured to make men out of boys."

"I stopped after two chapters because it was so boring," says Verhoeven of his attempts to read Heinlein's opus. "It is really quite a bad book. I asked Ed Neumeier to tell me the story because I just couldn't read the thing. It's a very right-wing book. And with the movie we tried, and I think at least partially succeeded, in commenting on that at the same time. It would be eat your cake and have it. All the way through we were fighting with the fascism, the ultra-militarism. All the way through I wanted the audience to be asking, 'Are these people crazy?'"

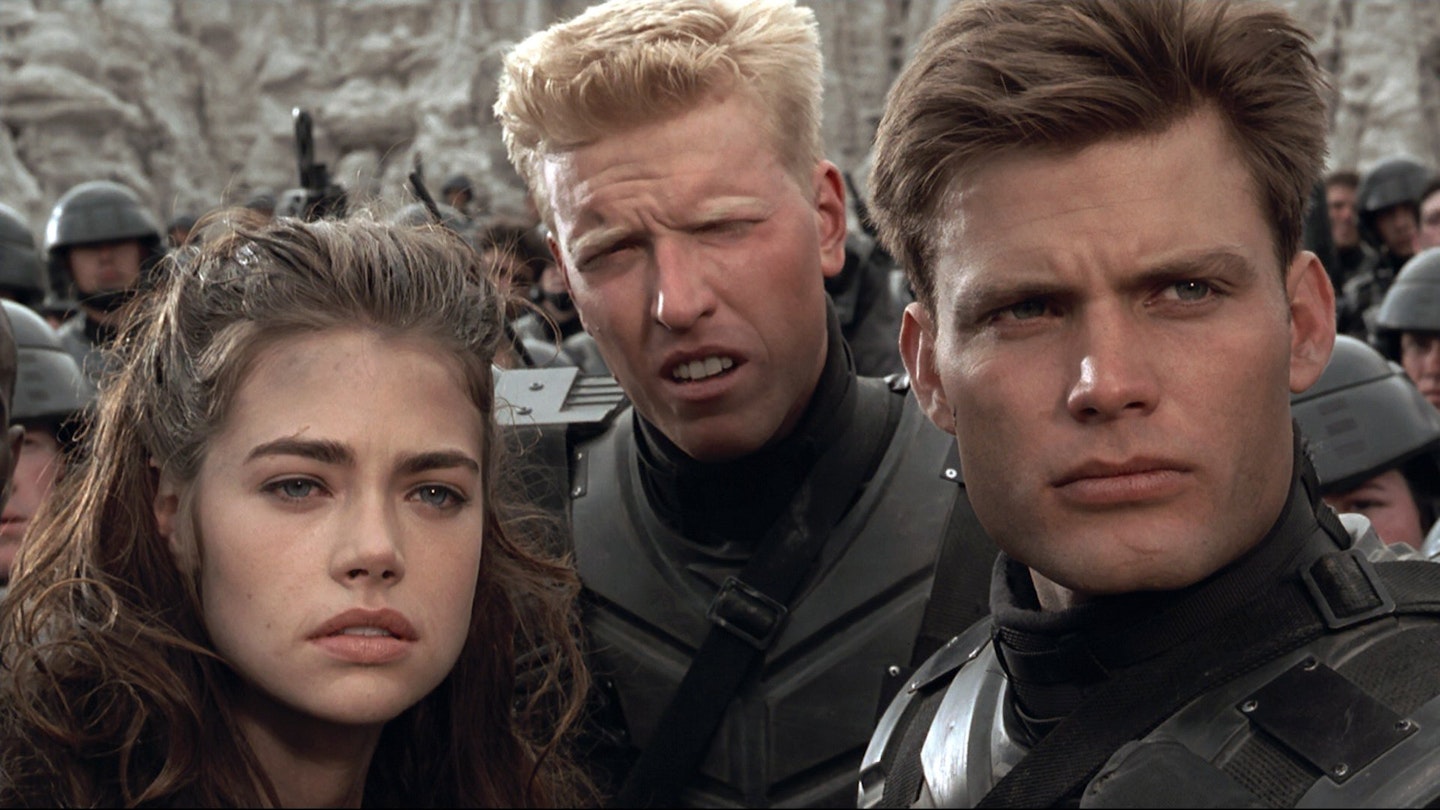

Verhoeven shot Bug Hunt At Outpost Nine (a working title) relatively uneventfully, working for the first time with a mixture of traditional miniatures and CGI (Phil Tippett, whose stop-motion animation had provided the iconic ED-209 sequence in RoboCop, had recently graduated to the technology and provided the herds of arachnids thundering over the desert landscape of Klendathu, in fact the badlands of Wyoming) while chasing his cast around the place with a broom, attempting to generate some of the fearsomeness of a 12-foot space ant."I wanted a cast that looked like the people in Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph Of The Will," he remembers when asked about the slightly synthetic Beverly Hills 90210 aspect to the interplanetary platoon's pulchritudinous appearance. "There was maybe a little of Riefenstahl's Olympia in there too, in the worship of the Aryan body and so on."

Those bodies would get typically Verhoevenesque exposure in what would become one of the film's most notorious scenes: the mixed-sex shower sequence. "In fact I'd done that in RoboCop too, but nobody seemed to notice," he remembers. "If you look when he is still a human being and they go into the police locker room, in the middle of the scene there is a woman there topless. No-one seems to notice. I thought, 'In RoboCop nobody noticed so in Starship Troopers I'll make sure they do.' The idea I wanted to express was that these so-called advanced people are without libido. Here they are talking about war and their careers and not looking at each other at all! It is sublimated because they are fascists."

Unfortunately a few members of the cast detected not just a subtle political and psychological critique of the authoritarian mind but somewhat typical sensationalism from the director who had, after all, delivered Sharon Stone's infamous leg-cross in Basic Instinct only five years before. "One cast member said they would only get naked if we did," says Verhoeven, "Well, my cinematographer was born in a nudist colony and I have no problem with taking my clothes off, so we did. It is strange, but of course Americans get more upset about nudity than ultra-violence. I am constantly amazed about that. I mean, I haven't seen any sex scenes in American film that are anything other than completely boring. A bare breast is more difficult to get through the censors than a body riddled with bullets."

On release, Starship Troopers would become Verhoeven's most fundamentally misunderstood film. Much to the director's dismay and irritation, the majority of American critics failed to see the film's precisely calibrated irony, accusing the director of himself being guilty of right-wing tub-thumping. "We were accused by the Washington Post of being neo-Nazis!" he says, obviously still irked. "It was tremendously disappointing. They couldn't see that all I have done is ironically create a fascist utopia. The English got it though. I remember coming out of Heathrow and seeing the posters, which were great. They were just stupid lines about war from the movie. I thought, 'Finally someone knows how to promote this.' In America they promoted it as just another bang-bang-bang movie." (And why on earth the hacks at the Post would think that a boy who had grown up under the Nazi occupation of his own country would suddenly show brown-shirted tendencies is even more baffling.)

Verhoeven was lucky enough to sneak Starship Troopers past the studio execs with only a few minor tweaks, mainly because Sony was in a period of turmoil with execs arriving and departing on an apparently daily basis. But the times they were a-changing, and the small, risk-friendly outfits that Verhoeven did his best work for were going to the wall, leaving him in the hands of the big studios.

"The people I worked with, until Starship Troopers, were Orion and Carolco, small, independent companies," says Verhoeven. "They had done Rambo and The Terminator. Ultimately they went bankrupt. But these were led by people that all felt that after choosing the director then everything should be in his hands, which is very European, of course. He's responsible, he gets the glory - or the blame, of course, if it doesn't work. It was only very late when these smaller companies began to disappear I became aware slowly about how American studios in general work. I had been protected by studios who were much more director-oriented." But by the early '90s, the writing was on the wall for the kinds of film companies for which Verhoeven had done his best work. Sadly, in America at least, soon it would be for him, too.

Postscript

Verhoeven abandoned American moviemaking after the failure of Hollow Man. ("Good," he says when Empire informs him that we won't be chatting about that film. "It is very boring. I felt that I failed to transform it. What I had made was an on-demand studio movie. I decided I did not want to do that again.") But one of the odd paradoxes of his career seen from the new millennium is that had he made that decision to abandon his home country and try for a Hollywood career now, he would be much more likely to be offered a remake of some '80s flick than the kind of low-budget but fiercely original movie that these three classics epitomise. Hollywood's accelerating propensity to devour itself, its inability to generate new ideas, leaves him depressed, particularly since it is now his movies that are getting cannibalised. After two direct-to-video sequels, a new Starship Troopers is in development; Brazilian director José Padilha is prepping a RoboCop remake, which follows a pair of sequels and live-action and animated TV series; and, having been spun out unsuccessfully into a 1999 TV series, Total Recall reappears in cinemas this August having been reimagined by Len Wiseman.

"I don't know about these remakes. I have no opinion," Verhoeven muses as the light fades. "I really don't know... Do they think they can do better now? I will see the Total Recall remake, because actually Colin Farrell is more like the character in the book - we had to change him because it was Arnold. But that Hollywood cannot come up with new ideas, though, that is horrible. I think it's horrible." And then a worse thought occurs to him. "And I hear they're going to make them PG-13, which basically I could never do..."

Bixby Snyder

He'd still buy that for a dollar.

Steve 'Doc' Nemeth spent a single day filming his RoboCop scenes as Bixby Snyder, who would, he was keen on telling us, "buy that for a dollar!" Snyder is the star of peculiar TV show It's Not My Problem, which everyone in Old Detroit is unaccountably fond of. If you ever wondered, it is, Nemeth reveals, supposed to be a "zany game show".

"What can I say?" he chuckles. "I was working with a beautiful blonde named Heather, and we ended up covered in cake. I've never seen such a mess! I'm glad I wasn't the one that had to clean up." Thrilled to be working with Paul Verhoeven - "I'd seen Soldier Of Orange four or five times" - Doc (as he prefers to be called) recalls that the director was "pretty damn good. He had a robust sense of humour, and he wasn't a slave-driver." After the quick shoot, however, Doc heard no more until the film was released, and was surprised at its immediate success and later cult status.

Never an actor by profession, Doc carved his main niche in "underground radio" during the late '60s, playing "rock, blues, boogie-woogie - all the good shit!" He continued to DJ throughout the 1980s, mostly on LA's KROQ-FM, and says Bixby Snyder is basically another version of his comedy radio-skit persona, "The Young Marquis".

Now "mostly" retired, Doc spends his Saturdays working at The Costume House in North Hollywood, where he's occasionally spotted. "Two weeks ago I was recognised for being in Independence Day," he laughs. "My lines were all cut, but you can still see me at one point, standing next to Randy Quaid." He didn't know about the upcoming RoboCop reboot, though: "Wow! I hope they call me!"

Mutant Mary

She made us wish we had three hands.

Do a quick Google Image search for "Lycia Naff": you'll immediately find a smart-looking woman in a power suit, a chick in a Star Trek uniform... and a woman with her shirt open, exposing three boobs. "So I hear!" blushes Ms. Naff. "I've never Googled myself and I never will. Ignorance is bliss!"

These days a successful journalist, Naff says she took the role of Total Recall's triple-breasted Martian hooker Mary "for a goof", thinking she wouldn't mind exposing breasts that weren't actually her own. "All three mammary glands are fake," she confirms. "The prosthetic was a large chest-plate that started at my neck and went down to my belly button. It took up to eight hours to apply; two make-up artists would have at me while I napped, in a very private room." Nevertheless, she says she did start feeling more shy as the shoot got nearer: "I sort of freaked out and started regretting that I took the part, but Paul [Verhoeven] went out of his way to make me feel comfortable. He promised me a better role in his next film, but it never happened!"

Naff's embarrassment led to her turning down multiple interview requests when the film was released, and she also avoided fan attention: "I decided not to answer every letter from every prisoner in the world who was writing me..." She later saw the funny side, though, when a friend presented her with a T-shirt he bought in a porn shop. "The image was from the movie, of me exposing the three breasts, and the caption read, 'Got Milk?'" Naff laughs. "I went down and bought all 30 of them, then gave them away as prizes during game nights at my house."

Career Sgt. Zim

He'd bring a nuke to a knife fight.

Clancy Brown, something of a sci-fi buff, was already well aware of Robert Heinlein's novel when the Starship Troopers script came through his door. The man best known as Highlander's The Kurgan was looking at the role of Career Sgt. Zim, who busts himself back down to private, the better to zealously fight intergalactic insectoids. "When I first read it, the politics didn't really dawn on me: it was just adolescent and gung-ho, and sort of good that way," Brown remembers. "But cut to however many years later and Verhoeven's doing it and it's completely subversive!"

Brown affectionately describes the director as "a nutbag", given to "jumping up and down with a bullhorn going, 'I'm a big fucking bug! I'll kill you!' I loved him; he was so much fun."

Tempers sometimes flared, but Brown says that even when Verhoeven was getting mad, there was always a glint in his eye. "You remember that whole beautiful sequence, with the ships and the planets?" he asks. "Paul looked at that with the FX guys, this breathtaking, incredible sequence, and he just went, 'This is bullshit! I can't put this in my movie! It's a complete lie!' I asked him what the hell was wrong and he said, 'The planets would never move like that!' He's basically a mathematician; his brain goes a million miles a second. He was like, 'You American actors are so stupid!' And then we both started laughing!"

Verhoeven's Starship Troopers is, Clancy believes, the director's warning to America. "It really exposes a lot of who he is, and how he thinks about the world, and especially us. He was saying, 'Be careful - this mindset is going to get you in trouble.' I think that warning still stands."