For the latest in our series of director-on-director interviews, Paul Feig (director of Bridesmaids and Ghostbusters) sits down to talk about Love Actually with its writer and director, Richard Curtis. This article originally appeared in Empire magazine, issue #335 (May 2017). Portraits by Steve Schofield.

Paul Feig: “I’m not a cynical guy. Even though the genre-jumping Howard Hawks is my favourite director of all time, I’ve always loved movies that aren’t afraid to simply entertain. Frank Capra, the king of what his contemporaries disparagingly called ‘Capra-corn’, is a particular hero of mine, unapologetically making such feel-good classics as Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, Meet John Doe and my favourite film, It’s A Wonderful Life. Capra wasn’t afraid to place ‘Making An Audience Happy’ at the top of his checklist, and audiences continue to respond by watching his movies again and again even after all these years.

The greatest movies are the ones you want to watch again and again.

When I first watched Richard Curtis’ film Love Actually, I got the same overwhelmed, emotional feeling I got back in film school in the 1980s when I saw George Bailey learn that taking care of his friends and family while living an honourable life made him “the richest man in town”. To discover a film this pure of heart and eager to please, made in one of the more turbulent times in recent history — post-9/11, Iraq War-era 2003 — felt like I had stumbled upon some sort of gift from the past. And yet there it was, an R-rated, British romantic comedy/drama that dared to proclaim that the greatest thing about humanity is our ability to love and be loved. Not making some sly statement about the hypocrisy of mankind; not some indictment of the general public’s desire for happy stories — just an honest-to-God hilarious, crowd-pleasing movie. The greatest movies are the ones you want to watch again and again, and Love Actually is one that’s religiously played on a loop every Christmas. So I couldn’t wait to meet its writer/director for the first time, and grill him on all things Love.”

Paul Feig: I have to admit, I didn’t see Love Actually until just a few years ago.

Richard Curtis: I thought you were going to say, “I didn’t pick it.” [Laughter] “I got a begging letter from Empire...”

Feig: “I haven’t seen it yet, but I hear it’s very good…” No, I actually didn’t see it when it first came out. It’s one of those movies everyone references, and I know and love everybody in it, so I finally watched it. And was blown away by how lovely it was. But let me back up a little bit. You’re responsible for one of my favourite shows of all time: Blackadder. So what was the journey for you like, from that to this?

Curtis: The funny thing is, Blackadder is not a very romantic, optimistic thing, even though it is in its own way joyful. But when I was doing TV, the one thing I found out is we couldn’t do anything emotional, really. Because people can agree on a joke much easier than they can agree on something that’s heartfelt. So I used up my cynical side, and by the time we got to the end of Blackadder and Not The Nine O’Clock News I had a yearning to do something with a bit of heart. Because in my real life love had completely and utterly dominated the landscape.

Feig: Yeah. Because you write so many great — for lack of a better term — romantic comedies. And you embrace the form so much and are so effective at it. How do you approach these stories?

Curtis: I didn’t actually know Four Weddings And A Funeral was a romantic comedy. It didn’t occur to me. While we were making it the films in my mind were Diner, Manhattan, Breaking Away, Gregory’s Girl... But it didn’t occur to me that that was a genre. I did know Notting Hill was a romantic comedy. I thought, “Well, I’ve done one by mistake. Now I know what I’m doing, I’ll do another.” But then I didn’t want to do a third. [With] Love Actually, I’d worked out a whole film about the Hugh [Grant] story and another about the Colin [Firth] story. But I decided it would be fresher to weave a lot of storylines together. To just have the best scenes from ten films.

Feig: I read an interview where you said you were sick at the time and so couldn’t write dialogue. You decided to take walks and just think up stories. I find that fascinating.

Curtis: Well, I’m not very good at story. As was revealed on the day when I realised Notting Hill has exactly the same plot as Four Weddings. [Laughs] It was like going out to look for a new house and ending up buying the one you’re living in already. Anyway, yes, I’d had a back operation and ended up walking around a lot, figuring out each strand. How does it start? What’s the complication? How do you end it? It was a joy. It took me back to my sitcom roots, where the plots have quick, simple arcs.

Feig: Did you write each story on its own?

Curtis: I think so. It’s all coming back now... The movie originally started with a conversation between some guys in a bar. Oddly enough I think it was a joke that Judd [Apatow] then wrote in a movie ten years later. So this guy was talking about how he fantasised a lot about his life’s death, because he thought there’d be a lot of women in cute black frocks at the funeral. Some of whom would hand him their phone number, saying, “I know it’s going to be complicated for you. It doesn’t have to be deep.” I thought, “Well, there’s one bit. What comes second?” Slowly building up this wave. I’m now feeling really mournful, because I’m remembering all the stuff that wasn’t in it. There was a big story about a schoolgirl who fell in love with another schoolgirl. And then we zoomed into a photograph at Laura Linney’s charity and it turned out these two Kenyan women were talking about how they didn’t like their daughters’ fiancés. There were a lot of fallers.

Feig: What I love about your writing is you find these little moments that aren’t life-changing — they’re little snippets of life. I also love the movie’s framing device of people at the airport. On Saturday Night Live in the ’70s, one of the short films was just slow motion of people running out of gates and hugging, set to a Simon & Garfunkel song, Homeward Bound. It just destroyed me, because that’s what life is.

I didn’t actually know *Four Weddings And A Funeral* was a romantic comedy.

Curtis: I’m glad I never saw it! I remember the moment I thought of that framing device. We were filming the Mr Bean film and I landed and got stuck. No-one picked me up. And I literally sat for two hours and watched three planes come in and saw this happening. I thought, “Oh, that’s proof of the pudding. Anybody that says that’s not what the world’s like is wrong.”

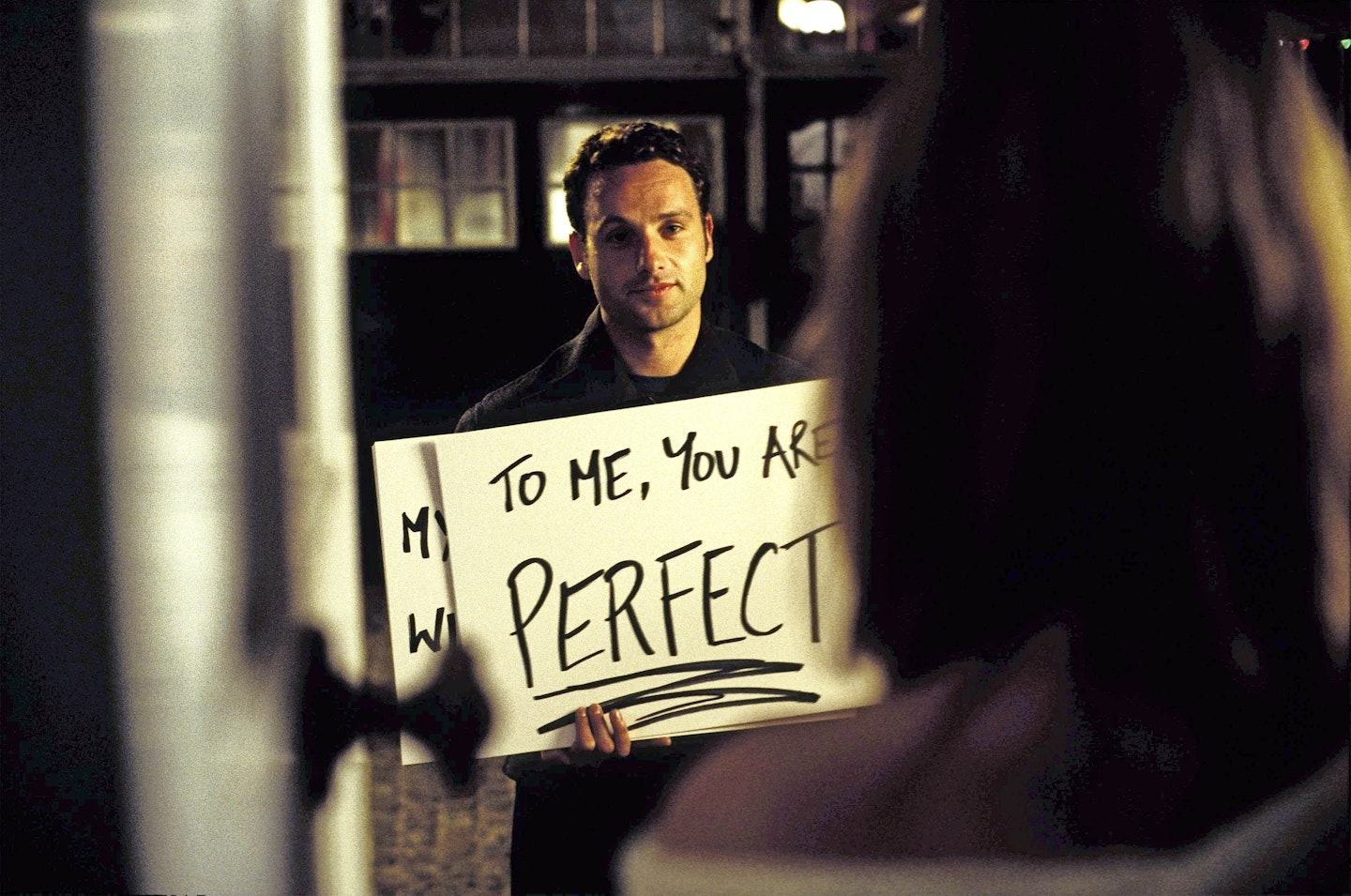

Feig: Tell me about the casting. Because the cast is crazy. It’s hysterical watching the Andrew Lincoln scenes now, because America really knows him as Rick Grimes.

Curtis: Back then it was a mixture of famous people and not-famous people. The problem now is all the not-famous people have become so fucking famous! Martin Freeman became the Hobbit. Andrew Lincoln joined The Walking Dead. Keira Knightley has had her career. It’s a different movie now to the one we made. But it was a lovely experience, because there was no pressure from the studio. Once Emma [Thompson] and Hugh were signed up they were happy. The weirdest story was Bill [Nighy].

Feig: Who is so brilliant.

Curtis: I was choosing between two people, one of whom is a very famous comedian and one of whom is a very famous actor. And I couldn’t decide. So I said to Mary Selway, my casting director, “Get me an actor for the readthrough.” She suggested Bill Nighy. I said, “Great,” because I had seen him in a couple of leftwing, cynical plays and I knew I didn’t like him.

Feig: Was he not famous at that point?

Curtis: No. He’d done a movie called Still Crazy, which hadn’t been a great success. And so he came along to the readthrough and was just so perfect we cast him five minutes later. And I’ve never done a movie he’s not been in since. We didn’t audition one person for that role except Bill.

Feig: This still blows my mind, but you’ve only directed three movies.

Curtis: And my hair’s white.

Feig: Well, one movie can do that to you. Were you always planning on moving towards directing?

Curtis: It was an interesting journey. I’m very, very, very unpictorial as a writer. You’ll spot that from my movies — they’re quite talky. As well as all being set on the street I live on. There’s not a lot of pictorial skill there.

Feig: But a short commute.

Curtis: Well, yes. I was always amazed at Mike Newell’s ability in Four Weddings to get to the truth by the choices he made. I didn’t know how he was doing it. It was like watching a chef: “Why does my steak taste so disgusting and their steak so delicious?” So when I saw Mike at work I thought, “I’ll never direct a film.” But I was incredibly obsessed with the performances and what beats I thought were or weren’t missing. I remember going up to him during one scene, after he’d done 17 takes of a really complicated camera move, and saying, “Look, we still haven’t got it.” He said, “Oh fucking hell. Another take for Mr Curtis!” I hid in the corner of the church and he shouted over at me, “Richard, yes or no?” I went, “Yes-ish...” He said, “Yes-ish means yes. Moving on!” On Notting Hill, Roger [Michell] had some tough times too, with me being a pain in the arse. I mean, after I started directing I thought, “It’s incredible he didn’t kill me.” So I only directed in order to not get killed. But I’m very disappointed by some of the things in the films I’ve done, just because I know they could have been done better by someone who’s better with the whole camera thing.

This idea that love is somehow sentimental is an insane fallacy.

Feig: I beg to differ. Because as I’ve found out over the years, everything else is in support of what the audience really cares about, which is those actors interacting. I’ve said to a lot of young filmmakers, if you’re going to pare anything away, lose the fancy shots. It’s all about pictures of faces.

Curtis: That’s the decision I’ve made. And you’re a better director than me, so you’ve made that decision with more to base it on. As we’d planned it, the most expensive shot in Love Actually was going to be right at the end of the movie, where eight out of the ten stories come together. One character was going to be driving over a bridge, one was going to be running under it, one was going to be at the Houses Of Parliament, and so on. It was going to cost us half a million dollars. Eventually the producer said, and I agreed, that I didn’t have the skill to do it. It was very lucky, because we would have ended up throwing that away on day two of the edit. Editing that film was like playing three-dimensional chess, because any scene could go after any other scene. We moved the pieces around so much, that shot would no longer have made any sense.

Feig: For a first movie as director, it’s hugely complicated. There are so many characters and locations. How did you feel the week before you started shooting it? I know I mostly panic.

Curtis: Well, I didn’t know any better! And I had to start again ten times, in a sense. When I think back to the boat film [The Boat That Rocked] or About Time, I had a lot of time to get to know the actors. On Love Actually they were gone before they’d begun. Maybe that was a good thing, because they didn’t get a chance to see through me. The worst moment for me was the Christmas scene in the Alan Rickman/Emma Thompson household. She’s about to open the present and get this big, sad surprise [receiving a Joni Mitchell CD from her husband instead of the gold necklace she knows he’s bought]. Then Emma turns to me and goes, “Richard, I don’t even know my son’s name. You haven’t given us any information about their Christmas traditions. But I have to act the mother of these children…”

Feig: Wow. My stomach just dropped into my shoes.

Curtis: I know! That taught me a big lesson: I hadn’t prepared enough.

Feig: I got yelled at by Joan Plowright once. We were rehearsing this movie I Am David. I’d blocked it all out, but suddenly she was moving all over. I was like, “Maybe we’ll try this...” And she goes, “If this is going to be a rehearsal where actors are asked for their input, I’ll continue. But if you’re just going to tell me where to sit, then just tell me.” It was awful. And she was completely right.

Curtis: That’s awkward. I can think of a few other dreadful Love Actually moments, but…

Feig: Tell me! I love the tough moments. What was the hardest story to get right?

Curtis: Probably Emma and Alan, because they had the realest story to tell. Hugh’s story had its tricky moments too. He didn’t want to dance. Hugh was fundamentally nervous that I was turning him back into a floppy-haired romantic lead. And the more he thought about it, the less likely he thought it was that the Prime Minister would dance down the stairs. But he changed his mind, due to contractual obligation. [Laughs] Look, a lot of the shoot was joyful. Most of it was. But I was scared from beginning to end every single day.

Feig: Were you feeling a lot of pressure, because of the unusual structure?

Curtis: Everyone thought it was a big gamble. People said, “Do we have to do this? Can’t we just have Hugh’s story?” But I didn’t want to do that. It certainly wasn’t a big hit: it made $60 million in the US or something, half as much as Notting Hill. But it’s had this lovely afterlife. I think partly because it’s a Christmas movie. And partly because it’s fun to watch because you forget what’s going to happen next.

Feig: The goal for anyone doing comedy is always multiple viewings. For me [Monty Python And The] Holy Grail is that way: you’re so happy when certain scenes come on…

Curtis: I’m ashamed to say that I just watched Step Brothers for the first time the other day. For my son Spike, who I saw it with, it would have been his 30th watch. It’s Paul Greengrass’ favourite movie of all time — that and The Battle Of Algiers.

Feig: Oh my God.

I do think that somehow this film is a gift from my younger, more optimistic self.

Curtis: I actually saw Love Actually recently for the first time in 15 years. My daughter booked us five seats for a midnight Christmas screening in New York. She said, “This is going to be great. There’ll be lots of people there — they’ll all boo when Heike Makatsch uncrosses her legs and sing along with the soundtrack.” We turned up and how wrong she was. There were nine people in the cinema, of whom we were five. Two were kissing, two were sleeping. But I liked the movie more than I thought I would. Because what’s been worrying me for the past few years is that it’s tonally inconsistent. Some of it’s very sweet, some of it’s really raunchy. I remember [Universal chairman/CEO] Stacey Snider saying to me, “It’ll make $50 milion less if you put the nudity in.” But I didn’t want to lose it. As a teenager I only went to the movies for the nudity, and I didn’t want to let my younger self down. [Laughs] As an older man, thinking of stopping, I do think I’m proudest of the sad stories, in particular Laura Linney’s one, which is sort of autobiographical. But I’m delighted by the optimism. Because I’ve always felt that the reason I do comedy is that I had such a happy childhood. I had such friends, I had an unbelievably blessed time at university. Why then would I focus on child abuse? I do think that somehow this film is a gift from my younger, more optimistic self. Even though I still believe in the fundamental message. This idea that love is somehow sentimental is an insane fallacy.

Feig: It’s everywhere.

Curtis: A million people in love in Los Angeles. One serial killer if you’re lucky. But yet, if you watch TV, there’s all these serial killers running around. There’d be nobody left alive except you and me. And I’d be about to kill you.

Feig: That’s our next movie! I feel like now, with the period we’re coming into in the world, we’re going to need more movies like Love Actually, to remind people that the human race is actually pretty wonderful. Which scene do people want to talk to you about the most?

Curtis: Well, it’s funny. When I did Blackadder, someone working with Rowan [Atkinson] said that 93 per cent of the mail he received was about the last two minutes of the last episode [in World War I-set Blackadder Goes Forth] where they all go over the top. And the first thing most people talk to me about is that scene where Emma cries. The sign stuff between Andrew Lincoln and Keira Knightley comes up a lot too. Not always unconditionally praised. I met a woman the other day who just referred to it as ‘the stalker scene’.

Feig: Oh God.

Curtis: “He was the best man! What was he doing there?” We’re doing some more sign stuff with the Red Nose Day film, which I’m shooting at the moment. [It aired on BBC One as part of Red Nose Day on 24 March.] It’s been touching to see many of the actors again and revisit those characters.

Feig: I’m lucky enough to have just seen the first two minutes of it, and it made me cry.

Curtis: I did toy with the idea of doing a proper Love Actually sequel. But I wonder what I think now about love, because I’ve experienced a lot of deaths and illness. I think therefore I would make a sadder film, and I’m not sure that would be great.

Feig: Called Love Possibly?

Curtis: Love Eventually. [Laughs] My son told me a good joke the other day. He said if he started an undertakers he would call it Four Funerals And A Funeral. That made me laugh.

This article originally appeared in Empire magazine, issue #335 (May 2017). Portraits by Steve Schofield. Subscribe to Empire here.{