There are movies galore that tell the lives of artists, and films beyond number that feature art work in some way, from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off to Bande Á Part to Skyfall. But some films have a relationship with art that is a little closer and more personal. Often, filmmakers include artworks in their production design plans as an inspiration or mood board; sometimes they build the whole look of their film around a piece of art (although we're not covering artists that actually worked on films here - sorry, Dali). Here are a few that stick particularly close to their source…

Inspired By:** **Colossus (traditionally attributed to Goya)

Giant robots. Giant monsters. Why, the fine-art roots of Guillermo del Toro’s latest couldn’t be more obvious. One of the images that most inspired the director when putting together his vision of Kaiju and Jaegers was this painting called Colossus, traditionally attributed to Goya (its authorship has lately been called into question, and there’s a movement now to credit this to one of Goya’s students) and in the collection of the Prado in Madrid. You can see the appeal for del Toro immediately as he tackled his story of giants roaming the land, although none of his Jaegers are as magnificently bearded as this dude. Let’s hope Goya’s even-more-sinister Saturn doesn’t inspire the Kaiju.

Inspired By:** **The Black Paintings (Goya)

M. Night Shyamalan’s latest film has a surprising link to Goya (him again). When the director visited **Empire **recently he told us that he had taken inspiration from Goya’s Black paintings, painted late in the artist’s life when the long grind of the Napoleonic wars and illness (possibly syphilis, perhaps depression depending on who you believe) had taken their toll. Goya painted some seriously dark and twisted scenes on the walls of his home in the south of France, which were painstakingly removed and preserved after his death. A few, like this Procession Of The Holy Office, show the sort of landscapes that feature in After Earth; others show mad gods eating their children and dogs dying in deserts. It’s pretty bleak stuff, basically, and has inspired a host of other artists as well as filmmakers (even some of the Bree scenes in Fellowship Of The Ring have a Black Paintings feel to them).

Inspired By:** **The Calling Of St Matthew (Caravaggio)

Martin Scorsese, as well as having a near-encyclopaedic knowledge of cinema, knows his arty onions – and it figures that he’d be a fan of Italian master Caravaggio, the original master of chiaroscuro. Between Scorsese’s religious background and his eye for light and shade, the paintings became an obvious inspiration for Mean Streets in particular. Scorsese told The Guardian: “I was instantly taken by the power of [Caravaggio’s] pictures. Initially, I related to them because of the moment that he chose to illuminate in the story. You come upon the scene midway and you’re immersed in it. It was like modern staging in film: it was so powerful and direct. He would have been a great filmmaker, there’s no doubt about it. He sort of pervaded the entirety of the bar sequences in Mean Streets. It’s basically people sitting in bars, people at tables, people getting up. The Calling Of St Matthew, but in New York!”

Inspired By:** **House By The Railroad (Edward Hopper)

American 20th century artist Edward Hopper’s paintings have an empty, desolate quality that fitted the isolated motel of Psycho rather well. This particular 1925 painting, of a Gothic farmhouse on a lonely plain, informed the look of the Bates house in some detail, with the steps up the hill from the motel even offering a visual nod to the railroad of the painting. Hopper was a keen fan of cinema and was apparently delighted that his painting had contributed to the film. Hollywood has generally repaid the compliment, with this painting in particular also a huge influence on Terrence Malick’s Days Of Heaven and a clear model for the homestead there.

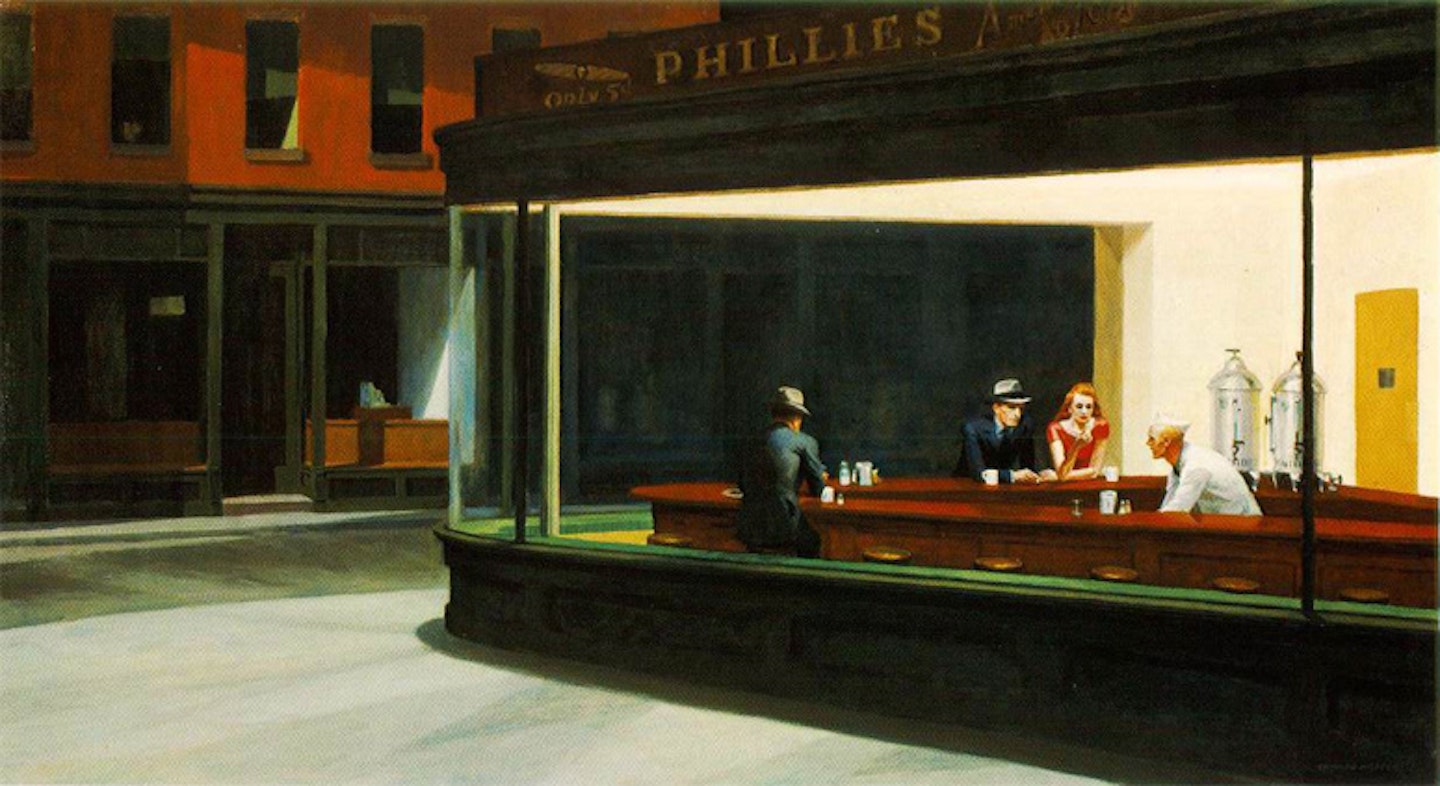

Inspired By:** **Nighthawks (Edward Hopper)

Another Hopper painting that’s often been referenced in films (and TV shows from The Simpsons to That ‘70s Show) is Nighthawks. There are explicit recreations of it in Wim Wenders’ The End Of Violence and Dario Argento’s Profondo Rosso, but it also served as a visual reference for Ridley Scott’s science-fiction masterpiece, with the painting’s colour palette faithfully reproduced onscreen. “I was constantly waving a reproduction of this painting under the noses of the production team to illustrate the look and mood I was after,” says Scott. Presumably, after a full day of this the production team would slope off to a quiet diner to escape the paintings being waved under their noses; however it happened, the influence comes across in Deckard’s isolated city life.

Inspired By:** **Study after Velázquez’s Portrait Of Pope Innocent X (Francis Bacon), which was modelled on Innocent X (Velázquez)

The film on this list with the deepest roots in art history is, perhaps surprisingly, Alien. You already knew that H. R. Giger designed the xenomorph, based on his own nightmarish and surrealistic work. But what you may *not *have known is that he was inspired by Francis Bacon’s melty-faced study of Pope Innocent X, itself based on the portrait of that pontiff by Spanish master Diego Velázquez. So the genesis of this film sees two of the 20th century’s masters and one 17th century legend conspire to bring us an acid-blooded nightmare monster. In any battle between Alien and Predator, therefore, Alien should rest assured of the full support of the art community – although it boggles the mind to imagine what Velázquez would have made of the creation.

***Inspired By: ***Napoleon Bonaparte (Benjamin Robert Haydon)

The final scene of this early Ridley Scott drama sees keen duellist Féraud (Harvey Keitel) forever barred from fighting his favourite opponent, whereupon he stumbles to a high bluff and looks out at the sun over an estuary – a scene that clearly echoes Benjamin Robert Haydon’s 1830 portrait of Napoleon at St Helena, looking longingly back towards his lost Europe (the pocket-sized Frenchman was Féraud’s idol). This is just one moment in a film thoroughly rooted in paintings of the time: see also, of course, Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, which took Hogarth as a model for its candlelit interiors.

***Inspired By: ***The Swing (Jean-Honoré Fragonard)

While the finished film moved in a slightly edgier direction (pictoral references on the walls of the production office included The Princess Bride), the original look for Disney’s take on the Rapunzel story was built around this painting by French painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Known for his hedonistic themes and chocolate-box cuteness, Fragonard flourished in pre-revolutionary France but was all but forgotten for the century that followed the Terror. It turns out paintings of flowers are instruments of aristocratic oppression, innit. Still, that didn’t stop Disney and its animators using this painting, in particular, to build their Rapunzel story around. The only real difference is that they replaced the swing with some really, really long hair, and dressed their leading man in rather less girly clothing than was popular in France's Ancien Regime.

Inspired By:** **Various, Andrew Wyeth

Inspired By:** **Various, Andrew Wyeth

Steven Spielberg’s a well-known collector of Norman Rockwell paintings – he and George Lucas loaned their paintings out to an exhibit a few years back – but fewer people know the influence that Andrew Wyeth had on his work. The first half of Jaws, with its formal composition and lengthy shots, shows a direct influence by Wyeth’s muted paintings of his home state of Maine. The artist said he loved Maine “in spite of its scenery. There’s a lot of cornball in that state you have to go through — boats at docks, old fishermen, and shacks with swayback roofs. I hate all that.” Similarly, Spielberg undermined the picture-perfection of Amity and gave it a jagged edge even before Bruce hove into view. Interestingly, the painter’s son Jamie, who’s also in the family business, painted a rather nice scene of a small dog and a Great White’s jawbone. Coincidence? We like to think not.

Inspired By:** **Pacific (Alex Colville)

Like Munnings, David Alexander Colville was a war artist who went on to a successful post-conflict career and has since inspired filmmakers with his canvases; like Hopper and Wyeth he was another American realist. Here, the Canadian’s 1967 portrait of modern alienation spills over with answered questions – What is the man pondering? Why the gun? How will he shift those tough-looking stains on the table? – and lent Michael Mann a readymade mise-en-scene for Heat. Study Neil McCauley’s (Robert De Niro) return to his beachside home and note the pose, the gun and the air of dramatic possibility, none of it good. No stains on the Mann table, mind you.

***Inspired By: ***The Morning Ride (Alfred Munnings)

A little susceptible to the clichés of the ‘roguish artist’ (see also: An American In Paris, Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins), recent release Summer In February nonetheless boasts a worthy addition to the painter-as-movie-star canon in AJ Munnings (Dominic Cooper). Actually, it’s his 1912 painting, The Morning Ride, that’s the star here. From the man there’s more boozing and carousing than you might expect for someone who’d go on to run the Royal Academy, but there’s also a nice scene in which he paints this, his most famous gee-gee – and its rider, Florence Carter-Wood (Emily Browning) – in a Cornish copse.

***Inspired By: ***Wheatfield With Crows (Vincent van Gogh)

A bit of a cheat considering that this 1956 melodrama is a formal biopic of van Gogh, but the great Dutchman’s work also inspired the look of Vincent Minnelli’s film and warrants a place on the list. For one thing, Minnelli deepened the yellows of his fields to match the artist’s palette using that friend of the auteur, spray paint; for another, there’re plenty of scenes in which Kirk Douglas portrays the anguished van Gogh at work, not least in painting his last great work, the brooding, menacing Wheatfield With Crows. Anthony Quinn steals the show with an Oscar-winning turn as tough-guy ladies’ man Paul Gauguin, but only because there’s no award for Best Supporting Landscape.

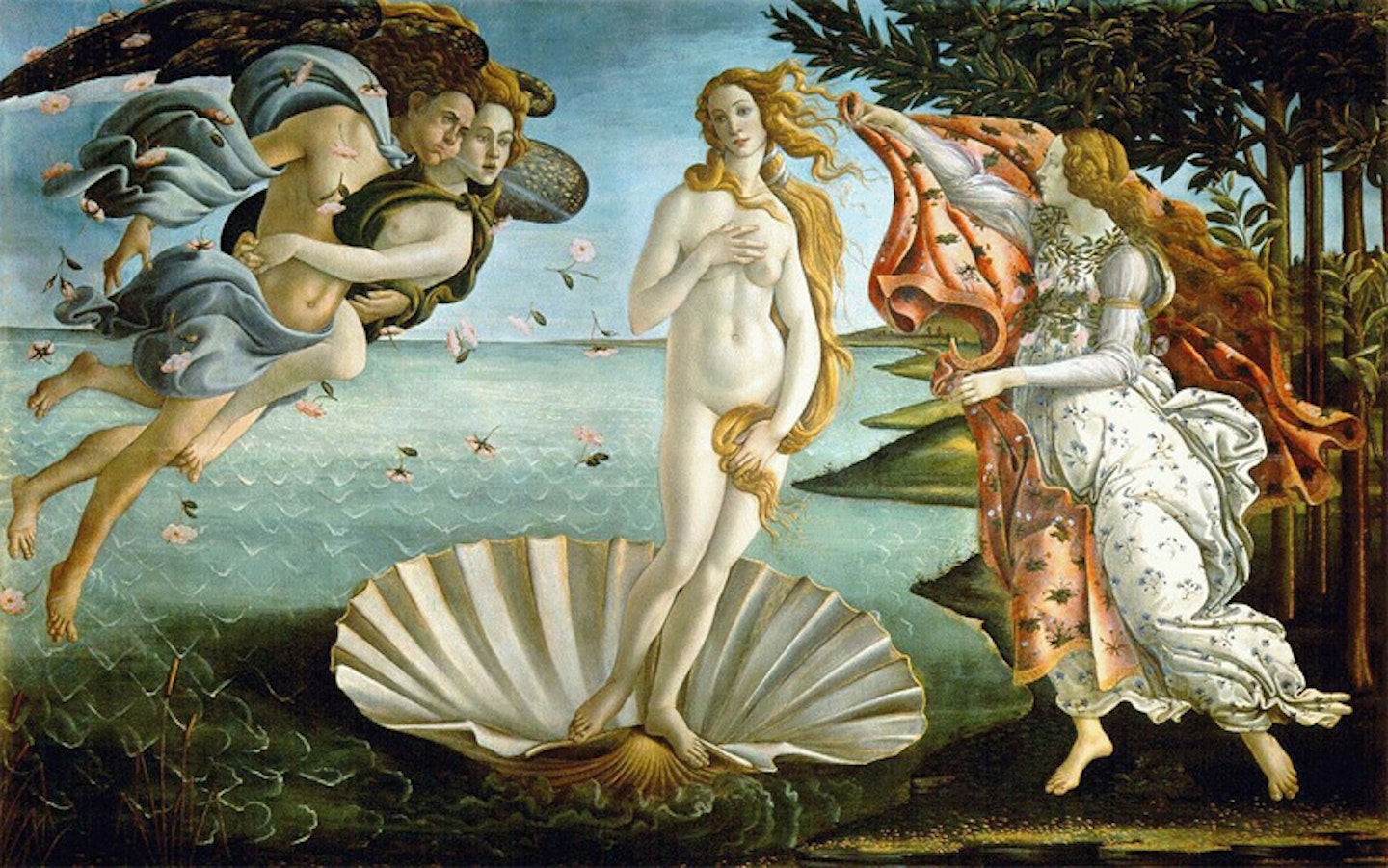

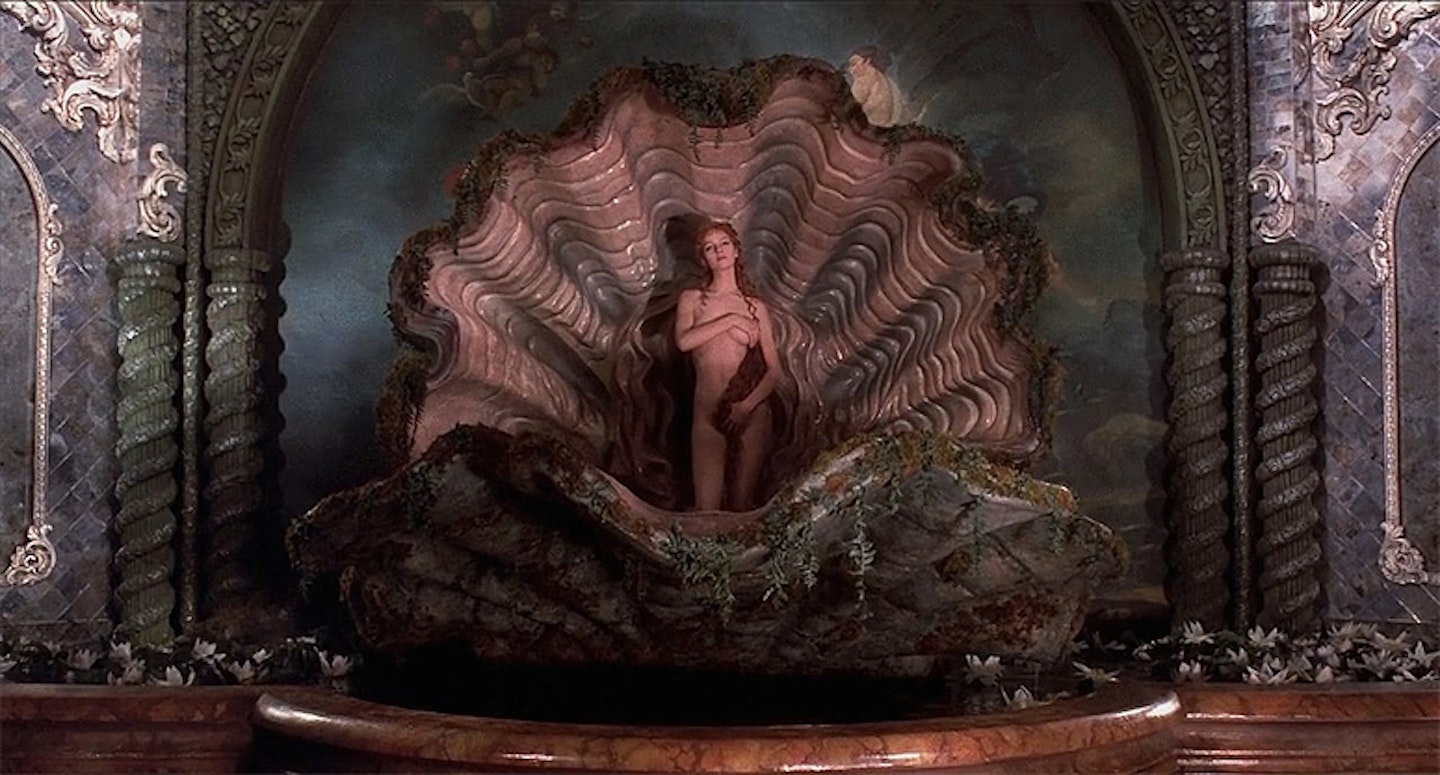

Inspired By: The Birth Of Venus (Botticelli)

There are few more beautiful examples of seafood in movies than Uma Thurman’s emergence from a giant clamshell in Terry Gilliam’s epic, at least if you discount the lobster bit in The Naked Gun 2½. We owe it all to Sandro Botticelli – ‘Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi’ for those not on familiar terms – and his 1486 masterpiece. Gilliam recreates the portrait beat-by-beat, complete with flying sea-nymphs and modesty-protecting drapery, and also references Pieter Bruegel and French artist Gustave Doré later in the film to further flaunt his paintyphilia. Hieronymus Bosch has also popped up regularly as a Gilliam touchstone, lending his carbuncled carnage and doom-ladden landscapes most clearly to Twelve Monkeys’ apocalyptic near-future.

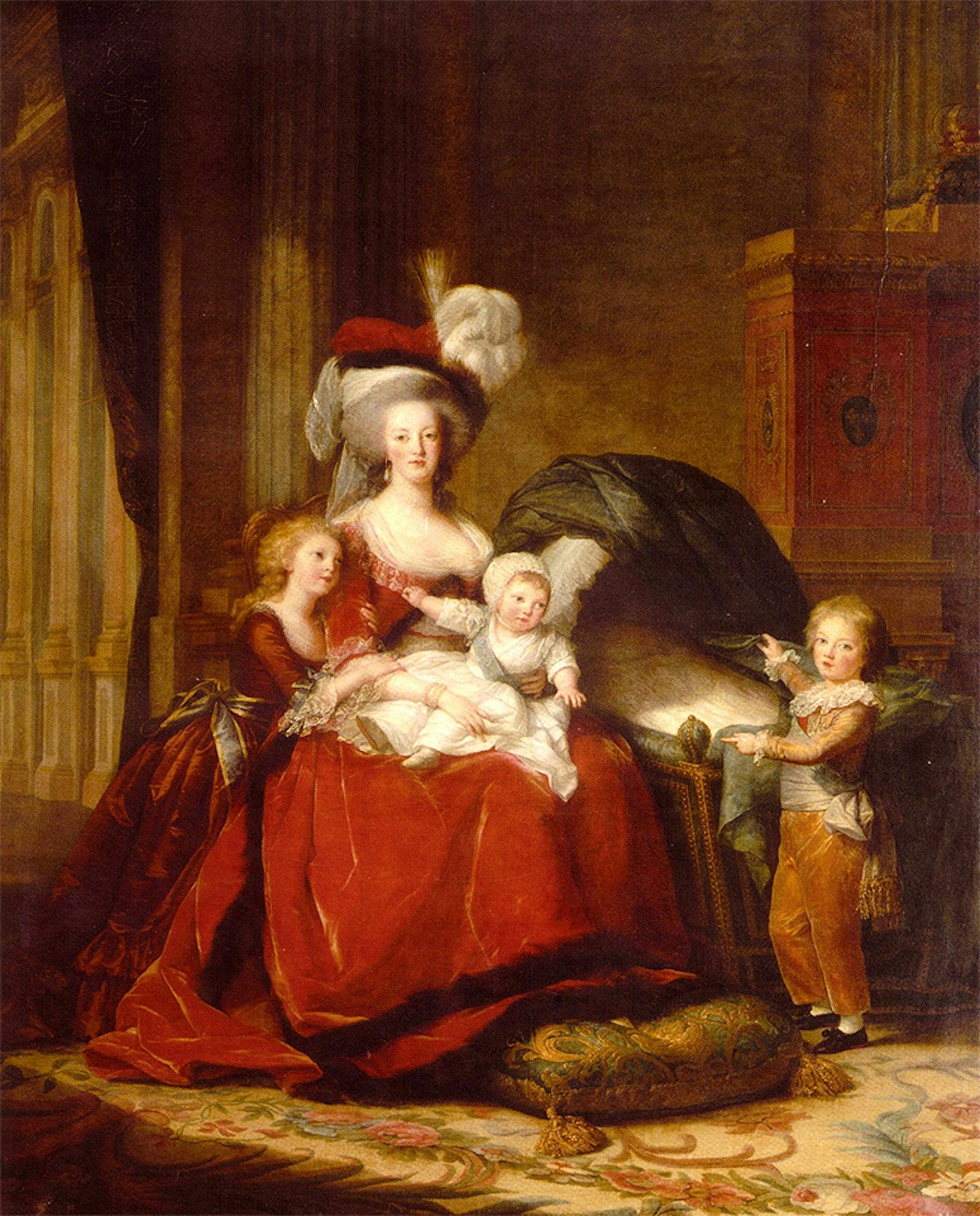

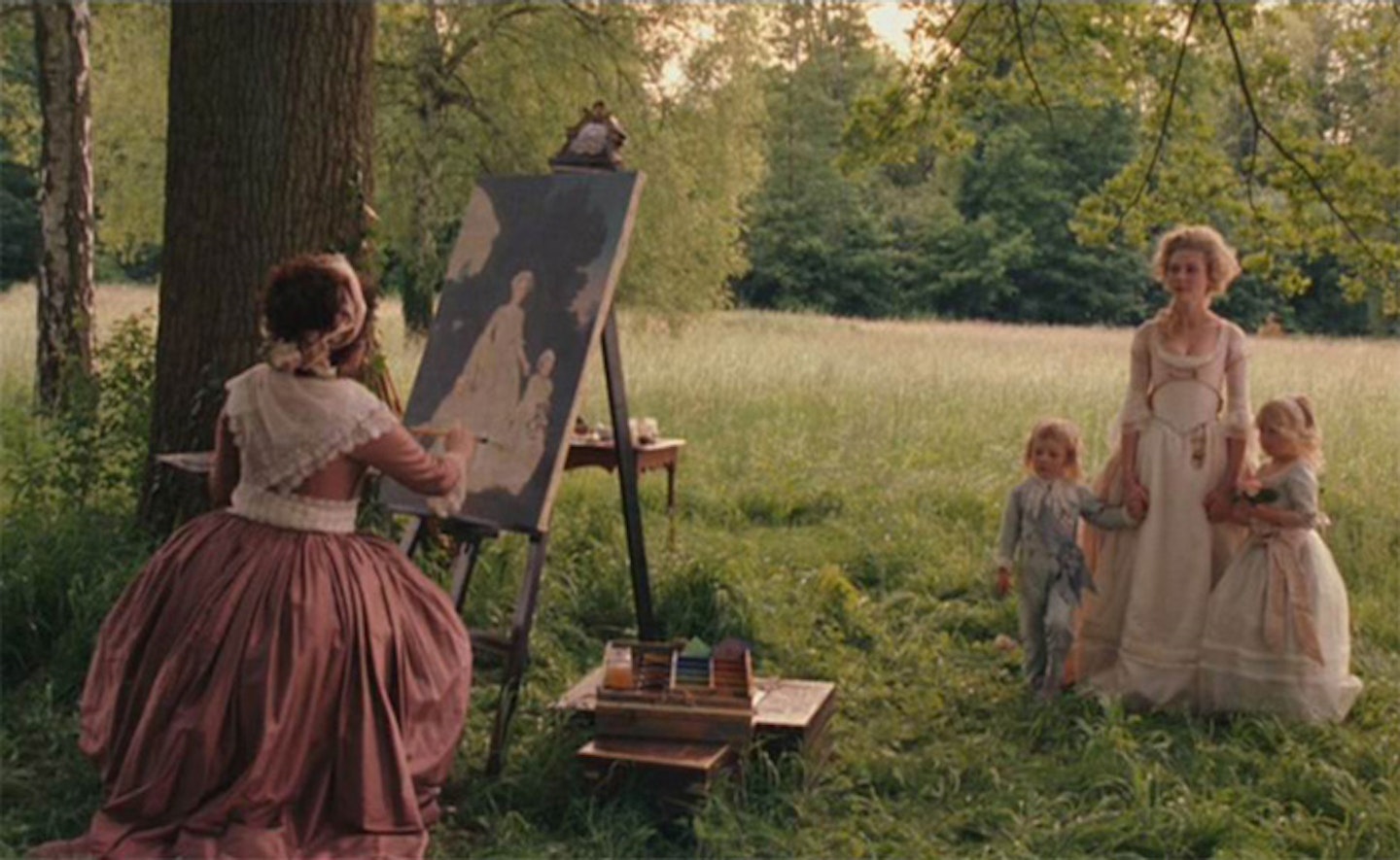

Inspired By: Portraits of Marie-Antoinette and her family (Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun)

Sofia Coppola’s punk biopic of the doomed French queen may have included some distinctly anachronistic pairs of Converse and Manolo Blahnik shoes, but she also took inspiration from the court portraits of the Queen painted by Rococo artist Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. Yes, a woman! Overcoming the sexism of the time in part thanks to family connections and also thanks to talent, the artist left more than 30 portraits of the Queen and her family, and went on to travel around Europe and paint Russian royalty after the French Revolution made her native land a less-than-hospitable place for a court painter. Vigée Le Brun’s sugary palette and pastel colours are clearly visible in the film, and a scene showing a woman painting the Queen is even included in the final cut.

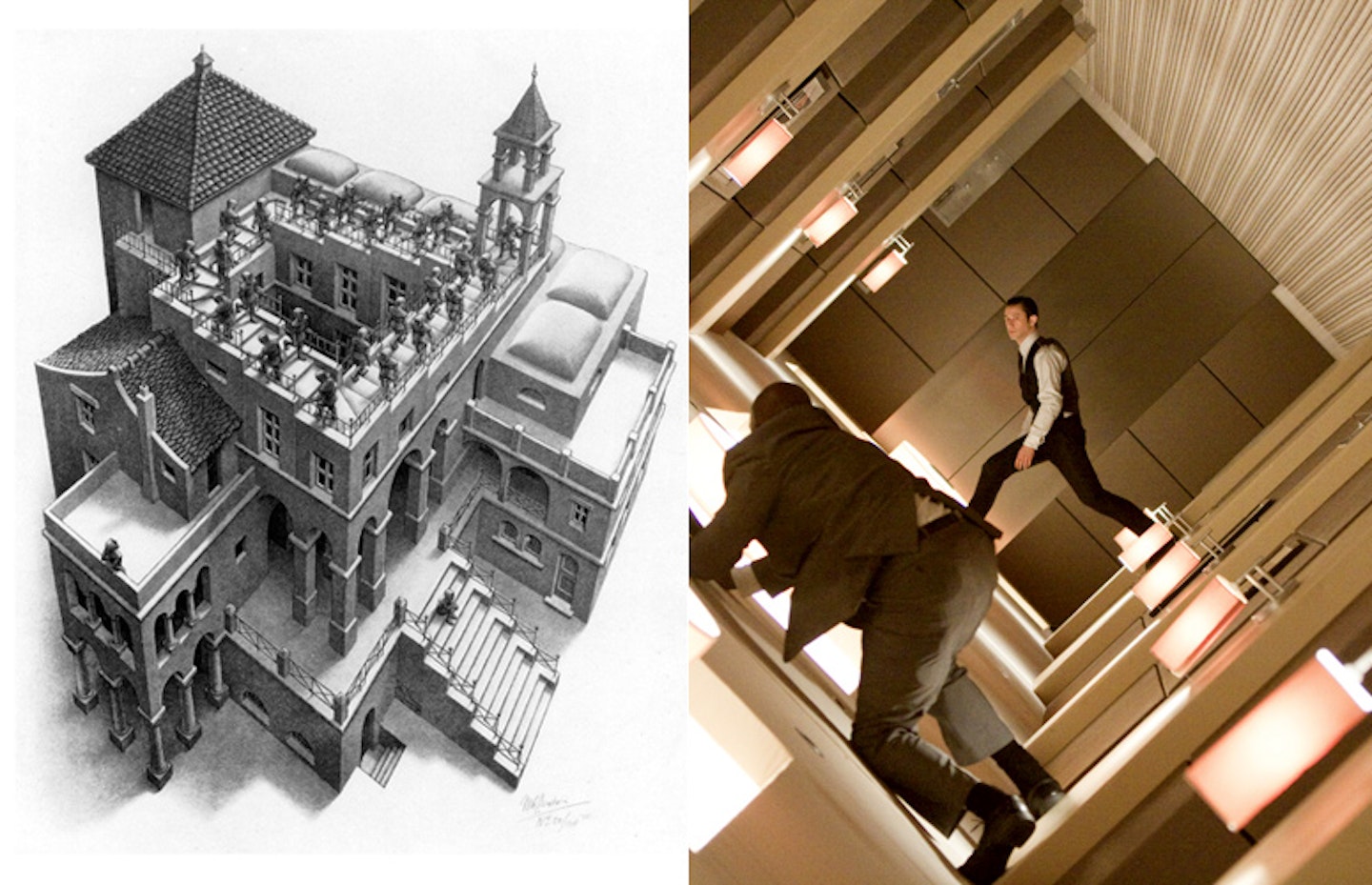

Inspired By:** **Relativity and Penrose Stairs (M. C. Escher)

M. C. Escher’s brain-bending paintings are a natural port of call for visual designers, and have cropped up in endless TV shows and games. On film his often-surreal inversions of natural laws have been more difficult to use, and aside from a memorable tip of the hat in Labyrinth, Inception is the film that’s made best use of them. In retrospect, of *course *a film set “within the architecture of the mind” would reference Escher, since his etchings are dream architecture brought to life and given that they can support the film’s twisting perspectives and competing gravity wells.