It’s time to celebrate movieland’s best one-timers – the debut directors who never stepped behind a camera again. Some were actors by trade who had a single story to tell, told it and then returned willingly to their craft. Some were stung by critical fury, box-office failure or just the endless vagaries of film financing and so abandoned the job for good (or at least to date). Some were Klaus Kinski. The M|A|R|R|S and Chesney Hawkeses of cinema, here are some of the most memorable one-hit filmmakers.

Film: The Night Of The Hunter (1955)

“Never work with children, animals or Charles Laughton,” counselled Alfred Hitchcock after clashing with his fellow Brit on Jamaica Inn. Hitch wouldn’t have enjoyed the set of Night Of The Hunter, Laughton’s one and only film as director. But standing tall among all the sprogs and farm critters, Laughton sparked James Agee’s rural noir masterfully into life.

A making-of doc, Charles Laughton Directs ‘The Night Of The Hunter’{

Film: Nil By Mouth (1997)

Extra points to Gary Oldman, who wrote and directed his sole credit. He also poured his heart, soul and a hefty chunk of his bank balance into a movie that required much from its cast (Ray Winstone and Kathy Burke, in particular) and audience, but rewarded both with a moving, unsparing and very, very sweary take on its director’s younger life. Like Terence Davies’s Distant Voices, Still Lives and John Boorman’s Hope And Glory, Nil By Mouth was a childhood selfie that won him praise and awards. Roger Ebert, a welcome patron for any first-time filmmaker, praised its “pain, humour and tenderness”, while BAFTA crowned it Best British Film.

Did all this adulation launch Oldman into a prolific directorial career? Sadly not, although Oldman is mulling over a second go with the loud hailer. “I have a script that I’ve been out with for a year and a half; I’m still trying to raise money for it,” Oldman told us recently. “It’s very difficult. It’s bigger than Nil By Mouth; it’s 19th century. There’s a magic number in the indie world, and in that in-between world – because I wouldn’t say this is commercial in the RoboCop sense. The indie world is about $4m and that other number is $20m; I can’t do it for $20m, I need more. I’d love to do it this year, but it’s tough.”

Film: One-Eyed Jacks (1961)

Bosley Crowther, The New York Times’ oft-caustic critic, lauded this wayward Western, singling out Marlon Brando for directing with “the kind of vicious style he has put into so many of his skulking, scabrous roles”. Characteristically, Brando had taken no prisoners in his directorial debut. He railroaded a young director called Stanley Kubrick off the project, demanded that Karl Malden co-star over Spencer Tracy and then went colossally over schedule and budget. Paramount chopped the film from a languid 270 minutes to a tighter but less coherent 140.

Despite the butchery, Brando would name it one of his favourite movies in his memoirs, although he also admitted to some minor teething troubles. “On the first day of shooting the cameraman handed me one of those optical viewfinders directors use to compose a scene,” he wrote. “I looked into it, shook my head and said, ‘I don’t know… it’s hard to tell what this scene’s going to look like because it’s so far away...’ The cameraman came over and gently turned it round. I’d been looking through the wrong end.”

Film: Harlem Nights (1989)

There are films by one-time-only directors that are straight-up masterpieces, films that hint at talent subsequently untapped and films that represent noble stabs at the craft. Eddie Murphy’s Harlem Nights is none of these. Harlem Nights is a film so bad that other bad films refuse to be seen with it in public. It’s a film that scored enough Raspberry nominations to make its own jam. Eddie Murphy’s Harlem Nights has been scientifically proven to decrease the life expectancy of all who watch it; like a comedy version of The Ring, only not as funny. Murphy, who painstakingly shepherded this ’30s-set passion project to the screen, could have blamed a dreadful script from which “fucks”, willy gags and assorted clunkers flowed like a torrent. Unfortunately, he wrote it.

Film: Paganini (1989)

If you were looking for someone who embodies the patient shepherding, logistical exactitude and perma-calm required of a film director, Klaus Kinski’s name would be down at the bottom of the list somewhere between Bruce Banner and the Tasmanian Devil. “Holy crapping god, are you kidding me!” would have been a reasonable response from actors upon receiving the script from a man who, let’s not forget, once spent two days trashing a single bathroom and threatened to kill Werner Herzog. Repeatedly. Instead, Kinski – who’d failed to persuade Herzog to direct his treatment of “devil violinist” Niccolò Paganini – cast his wife Debora and son Nikolai alongside himself in an occasionally on-the-nose but visually arresting biopic. Sadly, it was Kinski’s last film; he died only two years later.

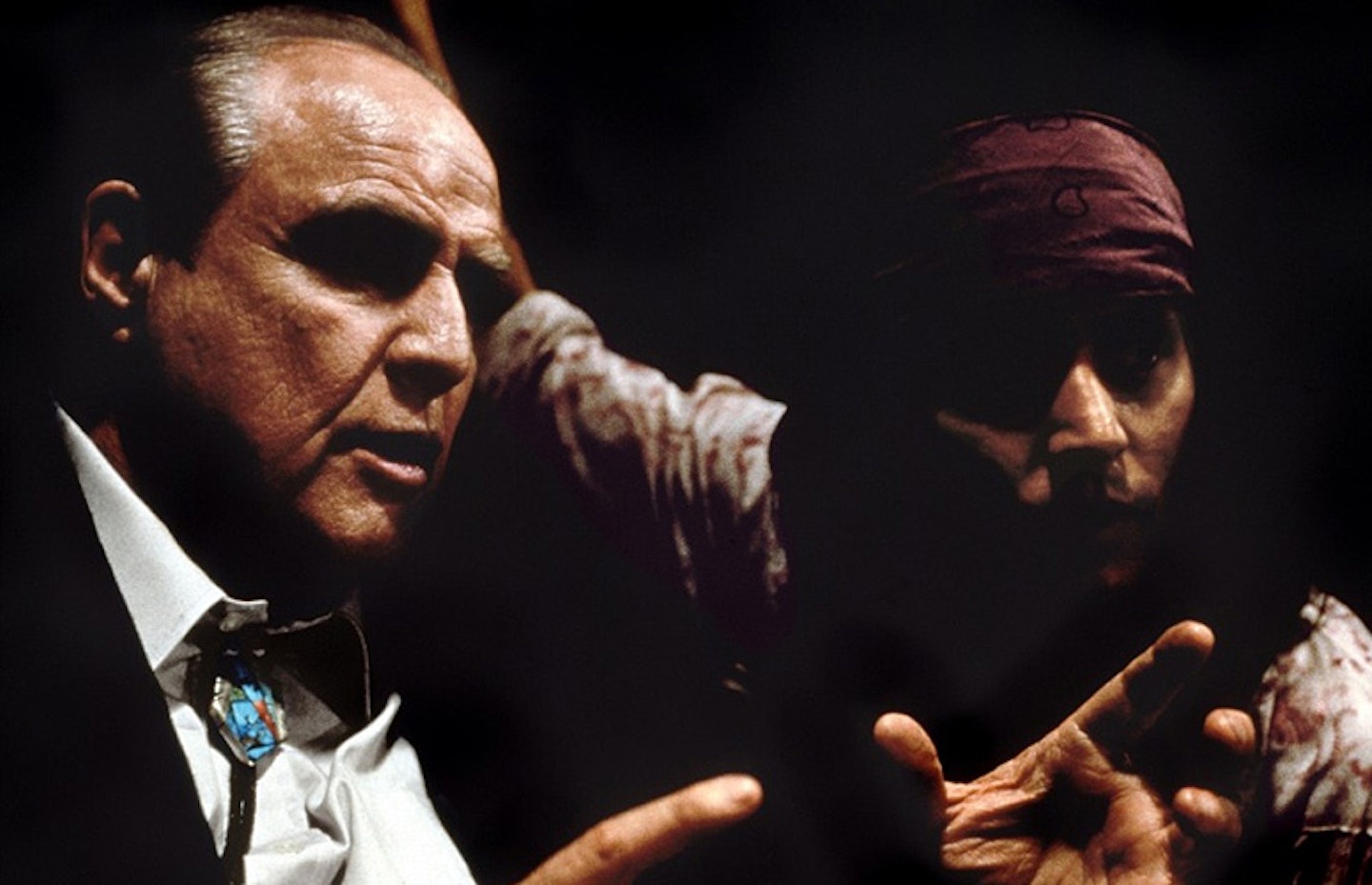

Film: The Brave (1997)

It’s a two-for-one on one-time directors in this misfiring drama. Johnny Depp enlisted his old pal and spirit guide Marlon Brando to play a snuff movie director who offers an alcoholic, destitute Native American $50,000 to end his life on camera. The film had a similar effect on Depp’s directing ambitions when American critics poured scorn on it in Cannes. Variety dismissed it as a “turgid and unbelievable neo-Western” – and that was one of the kinder notices. “This was one of the most difficult things I've ever done,” he explained on its ill-fated promotional trail. “It just about ripped me to shreds." The Brave was never released in the US – it remains rarer than unobtanium in any format – and has achieved an infamy in Depp’s career matched perhaps only by The Tourist.

Film: The Players Club (1998)

It probably won’t get a Criterion Collection re-release any time soon, but Ice Cube’s slick comedy-drama showed off his broad skillset and made him a minor mint to boot. There aren’t many filmmakers who can boast the rapper/actor/writer/death-certificate-issuer’s range, and expect that to remain the case until Abbas Kiarostami starts dropping lyrical bombs. Cube, who was 28 when he made it and had cut his teeth directing music videos, also wrote this Magic Mike-y tale of women trying to turn a buck in a strip club. Bernie Mac popped up as the club owner and Jamie Foxx as a DJ, but there’s no sign of early Korean Jesus, alas.

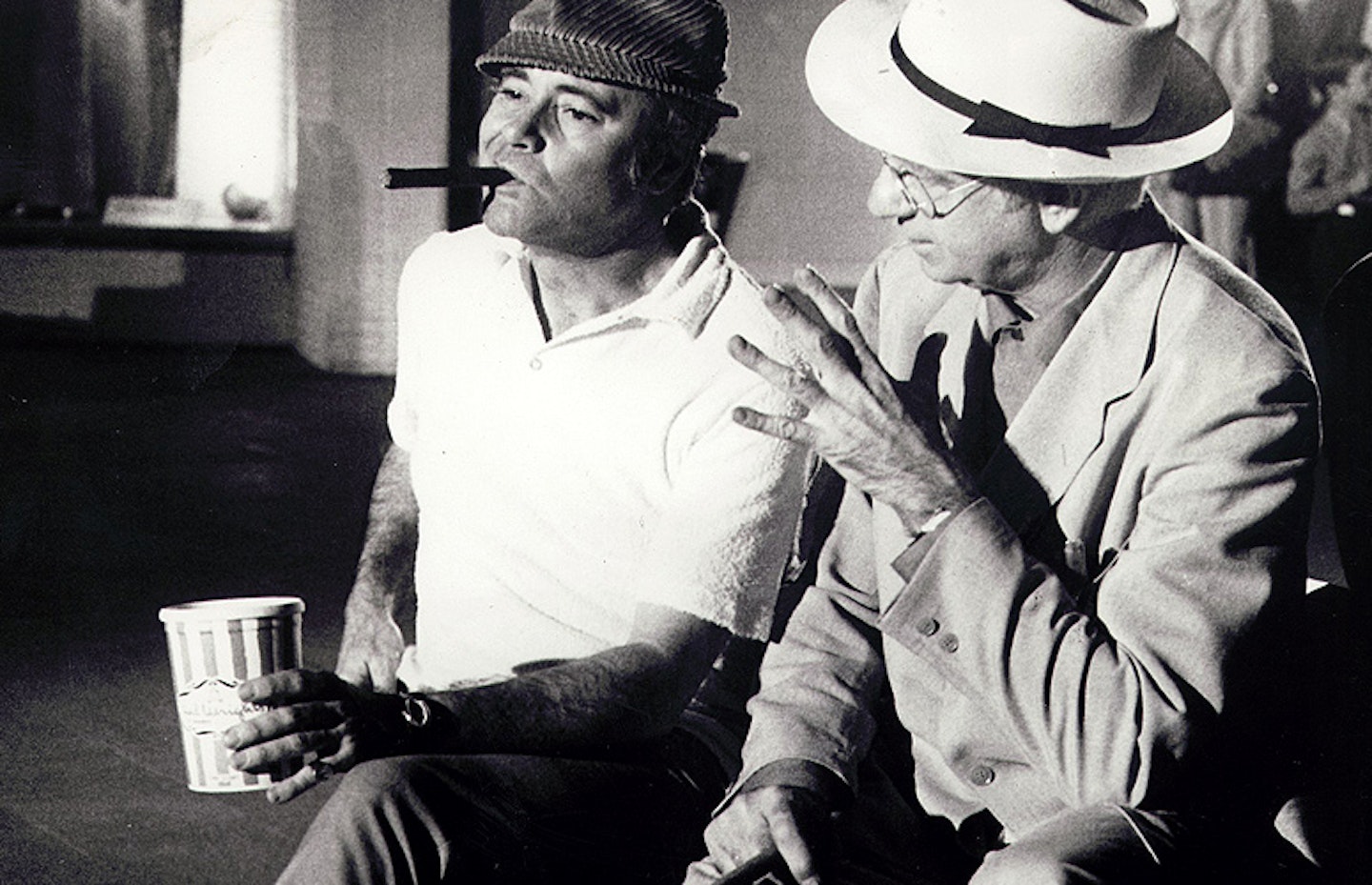

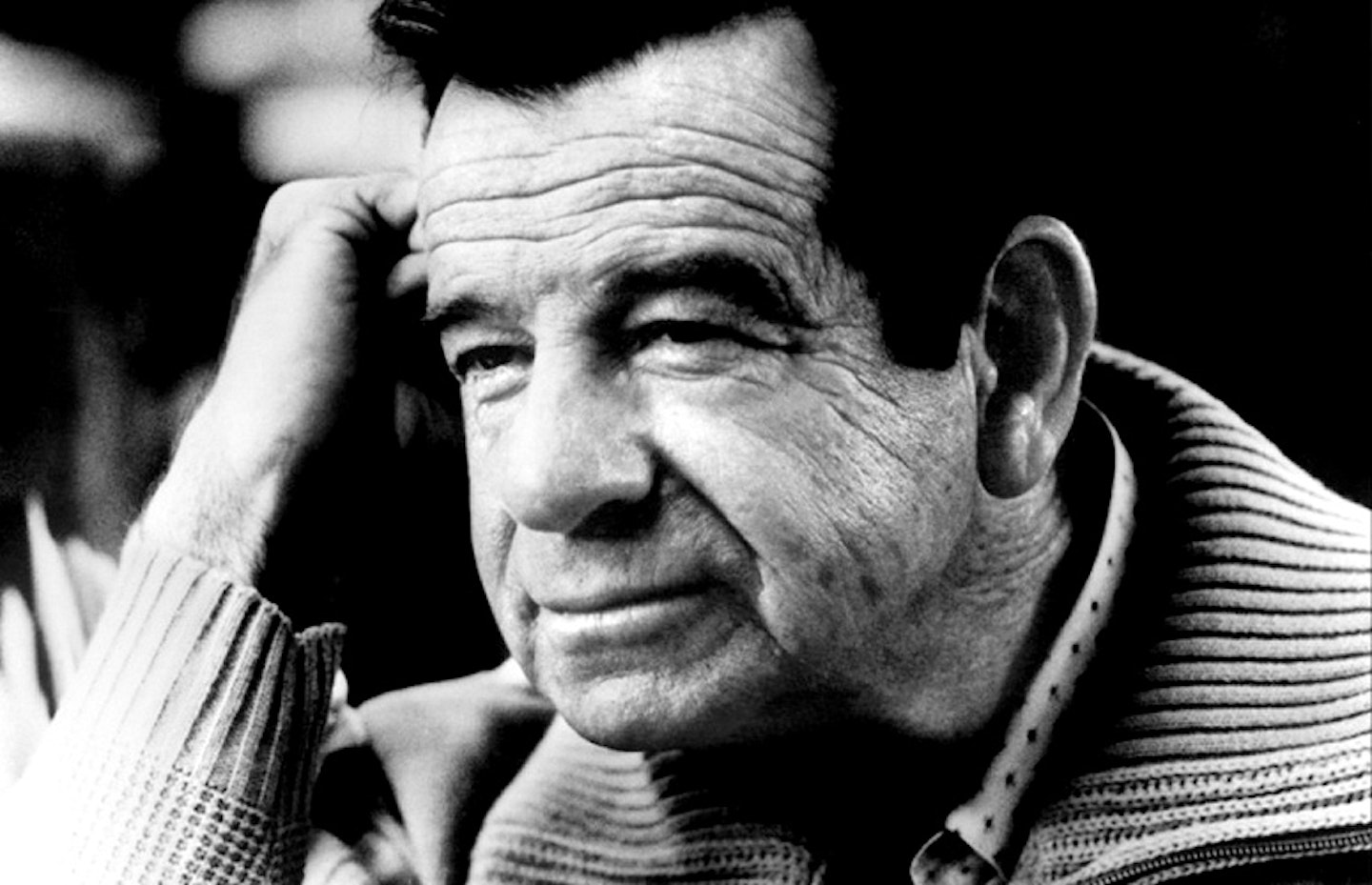

Film: Kotch (1971)

Jack Lemmon directed his old pal Walter Matthau in an Oscar-y effort that begs the question: why didn’t he direct again? The truth is that, like many actor-turned-directors, he found the experience exhausting and emotionally arduous. Not all critics loved it – Roger Ebert compared it unfavourably to Clint Eastwood’s debut Play Misty For Me – but the Academy lapped it up. Fittingly, Lemmon directed his friend to a Best Actor nod – Matthau lost out to Gene Hackman and The French Connection – and helped him channel his tart-but-endearing screen persona into a winning portrayal of a man growing old (dis)gracefully.

Film: Gangster Story (1960)

The other half of The Odd Couple also has a single directorial credit to his very famous name. Like Jack Lemmon’s Kotch, Gangster Story is not one that would live with the greats, but it’s a Matthau curio that completists can find here{

Film: The War Zone (1999)

A deceptively jaunty opening gave way to a bone-crunching family horror in Tim Roth’s solitary directorial gig, an adaptation of Alexander Stuart’s brute-lit novel that had personal resonance. “I'd been wanting to direct a film for years and told my agent to start looking for a script,” he recalls. “It was the first one that came through the door. If you are a survivor of abuse and you get the opportunity to tell a story about that subject, then you can really get in there and tell the truth. It was a fantastic chance for me to exorcise a lot of demons.”

Scenes shot in a Devon bunker were so hard that Ray Winstone, the abusive ‘Dad’ character, came close to walking off set, but Roth held cast morale together long enough to commit his Alan Clarke-y drama to film. A long-awaited second movie may not be far off. “It’s a matter of me just committing to it,” Roth revealed on the Empire Podcast, “and saying, ‘Okay, I’m going to take two years off to direct. I just want to get the kids into college first.” Watch this space.

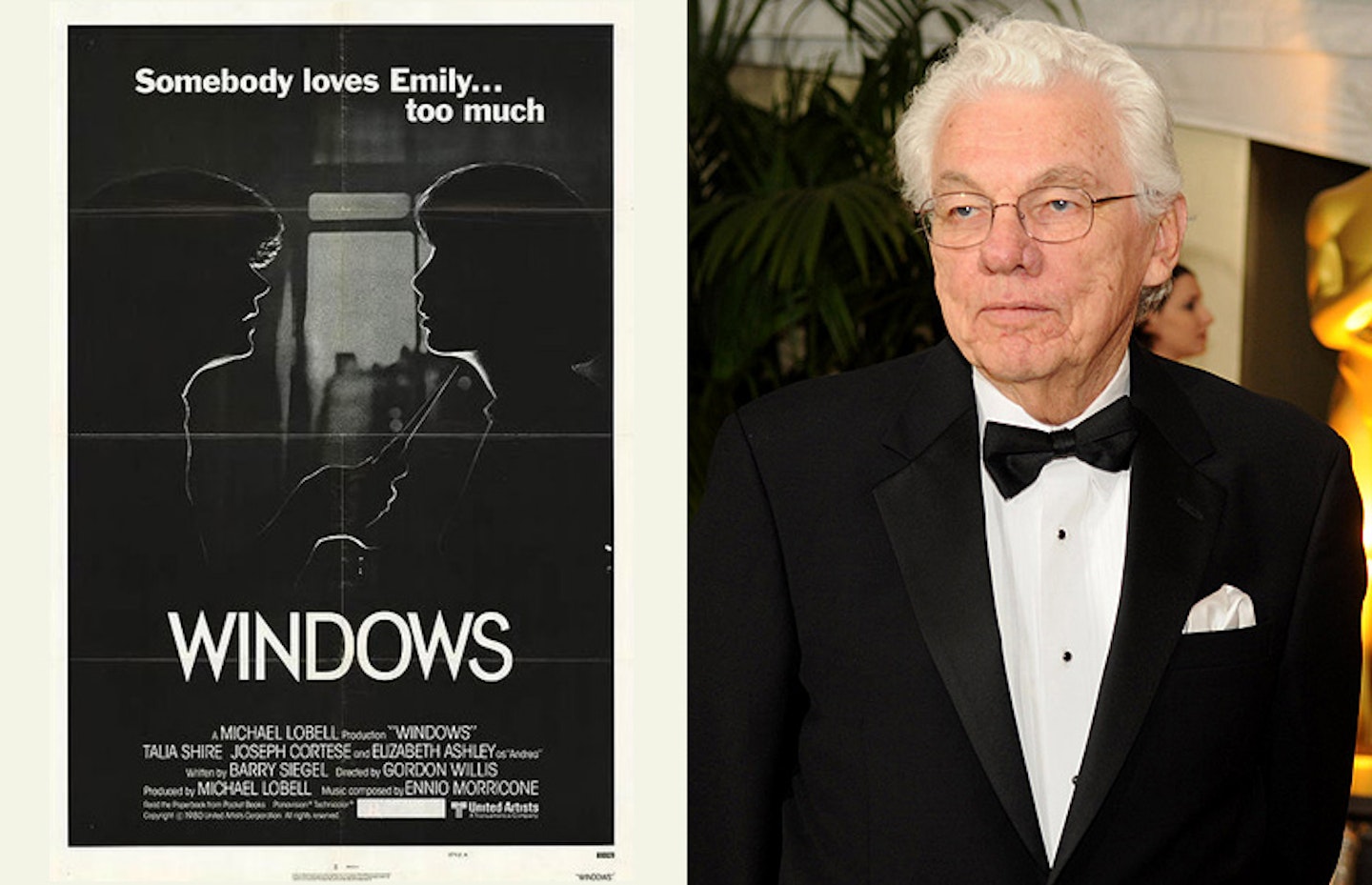

Film: Windows (1980)

Fellow DP-turned-director Wally Pfister will hope to improve on Gordon Willis’s short-lived filmmaking career with his first film, Transcendence. The Godfather and Annie Hall cinematographer – a man Francis Ford Coppola once compared to a Renaissance artist – was painting by numbers in a boiled ham of a thriller that had Talia Shire as the diffident prey of her lesbian neighbour. Willis had worked extensively with Alan Pakula by this point, but couldn’t quite overcome script problems to channel Pakula’s mastery of tension, nor an ending that makes Basic Instinct look like Persona. Willis, who later confessed to disliking the experience, returned happily to DP duties. "I've had a good relationship with actors," he reflected sanguinely, "but I can do what I do and back off. I don't want them to call me up at two in the morning saying, 'I don't know who I am’."

Film: Sky Captain And The World Of Tomorrow (2004)

The strange and unlikely tale behind this fantasy-adventure involves major leaps of faith, pioneering effects work and a young dude spending unhealthy amounts of time in his bedroom. That man, CalArts computer whizz and Zemeckis-in-waiting Kerry Conran, spent six years working on his Metropolis-and-Superman inspired blockbuster, sinking heart and soul and a major portion of his youth into a greenscreen confection that producer Jon Avnet financed and populated with big-name actors. Even the wildness of its premise, some warm reviews and the presence of Jude Law and Angelina Jolie couldn’t stop it flopping at the box office. Hollywood, an unforgiving place for a newbie filmmaker with one loss-making movie to his name, has yet to give Conran a second go.