It was an age of big hair. An age of power ballads. An age of guitar-chugging, leather-clad men and huge-voiced divas. An age where a movie tie-in song would cling to the number-one spot like a limpet, and videos were little more than filmtrailers. It was the age of the.. Popbusters!

But why did it end? And how? Empire charts the life-cycle of a movie-marketing phenomenon.

This article first appeared in the June issue of Empire magazine. Subscribe today{

IN 1982, THE GLOSSY NAVAL DRAMA AN OFFICER AND A GENTLEMAN WAS IN POST-PRODUCTION. Composer Will Jennings had written a grandstanding duet called Up Where We Belong, which director Taylor Hackford gave to Blues foghorn Joe Cocker and moderately successful singer-songwriter Jennifer Warnes. Don Simpson, then president of production at Paramount, told Hackford, “Look, I love the movie, but the song is no good.” His boss Michael Eisner shared his dislike. Hackford and Paramount went to war over the tune, with Simpson even commissioning Neil Diamond to write an alternative. Eventually Hackford threatened to remove his name from the film unless he got his way.

That November, Up Where We Belong topped the Billboard Hot 100 chart, staying in the Top Ten for three months and winning an Academy Award, a BAFTA and a Golden Globe. Undeterred, Simpson bellowed at Hackford, “It’s a rotten fucking song. It should never have been a hit.” A quarter of a century later, perhaps the thing people remember most from An Officer And A Gentleman is that song (that sound you hear is Don Simpson swearing in his grave). The film was even marketed with the tagline, “It will lift you up where you belong.”

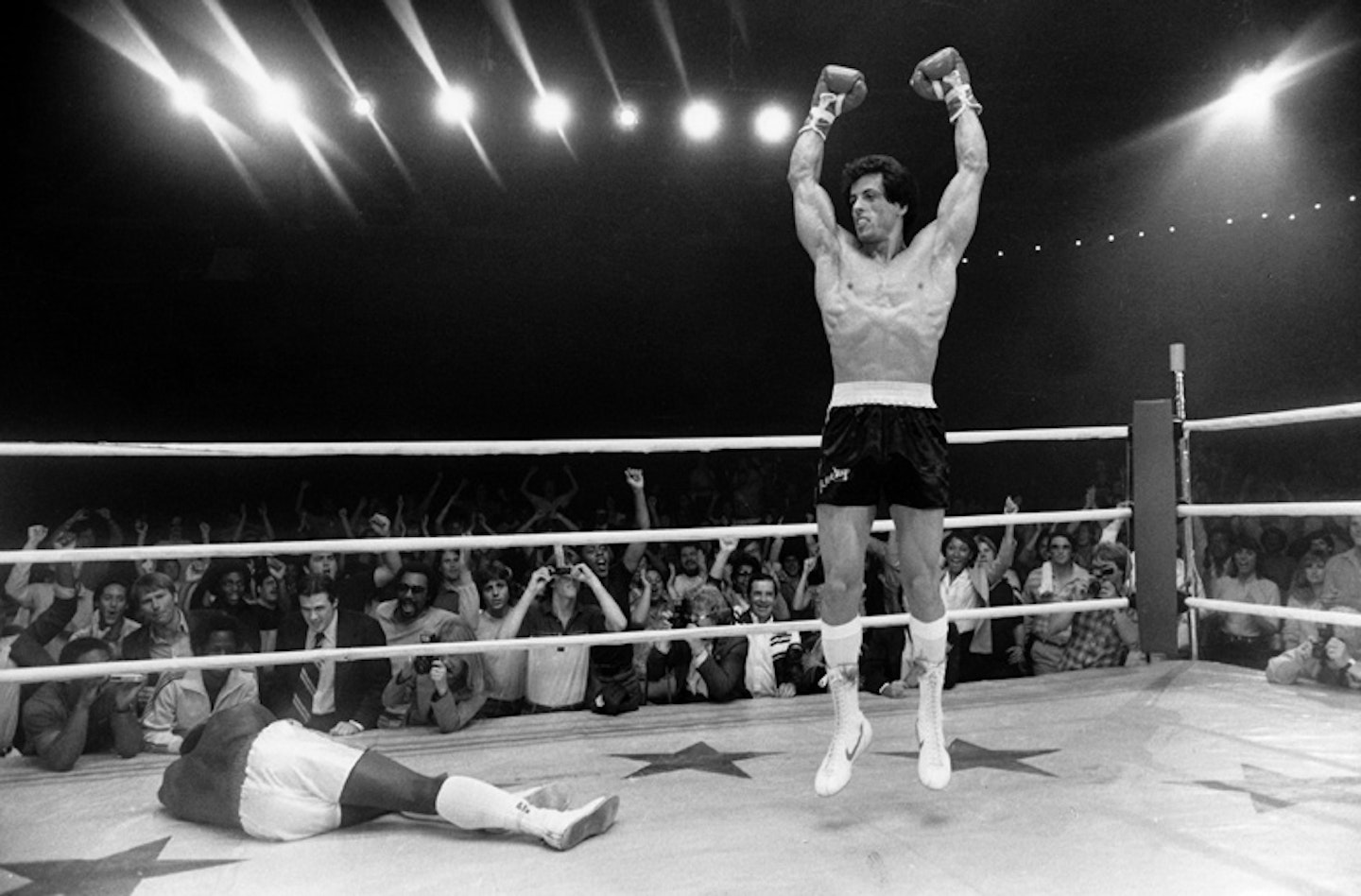

What nobody realised at the time was that Up Where We Belong, along with another of 1982’s monster hits, Survivor’s Eye Of The Tiger, from Rocky III, would ignite a trend that would rip through Hollywood like brush fire — namely the use of huge, uplifting theme songs that would be nailed into moviegoers’ brains like tent pegs. Think Bryan Adams’ (Everything I Do) I Do It For You, Roxette’s It Must Have Been Love or Celine Dion’s My Heart Will Go On. For the sake of clarity — and the fun of making up new words — let’s call them popbusters.

Of course, there have been hit movie songs going back to the 1930s. Early recipients of the Academy Award for Best Original Song included The Way You Look Tonight (Swing Time), Over The Rainbow (The Wizard Of Oz) and White Christmas (Holiday Inn). Subsequent years brought the likes of Que Sera, Sera (The Man Who Knew Too Much), Moon River (Breakfast At Tiffany’s) and Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head (Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid). And a hit song was, of course, integral to a Bond film or blaxploitation flick.

But the makers of big commercial pictures felt no particular obligation to commission a song unless it was a musical or the star was a famous singer; Star Wars did okay without the help of, say, Reach For The Stars (Luke And Leia’s Theme). Then the game changed with another of 1977’s box-office giants: Saturday Night Fever. On its way to becoming the biggest-selling soundtrack album to that point, the disco behemoth broke new ground in using songs as marketing tools. When the film was given a PG recut to net viewers more interested in singing along to the Bee Gees than pondering the tribulations of working-class Italians, the publicity material asked: “Where do you go when the record is over?”

But Saturday Night Fever, like Grease, was still a movie with music at its core. The next upheaval came in 1980 when producer Jerry Bruckheimer commissioned Debbie Harry and Giorgio Moroder to write a song for the opening of American Gigolo. The result was Call Me, the biggest hit of Blondie’s career, and great publicity for

a movie distinctly light on song-and-dance scenes.

After Simpson and Bruckheimer came the deluge. Throughout the ’80s, the popbuster seemed unstoppable. Burgeoning music channel MTV throbbed with videos that were little more than extended trailers. Soundtrack songs topped charts worldwide before the movies were even in theatres. Kenny Loggins was suddenly a big deal again.

But in 2008 it’s a different story. Many blockbusters settle for an old-fashioned score, Oscars for Best Song go to such leftfield operators as Three 6 Mafia and the couple from Once, and the blaring action movie anthem has been reduced to spoof-fodder in Team America: World Police. What, in the name of Loggins, has happened to the popbuster?

THE TWO BIG MOVIE SONGS OF 1982 EPITOMISE THE TWO MAIN TYPES OF POPBUSTER: Up Where We Belong is the historic ballad about undying love and mixed metaphors (“The road is long and there are mountains in my way/But we climb the stairs every day.” Stairs? On a mountain?), while Eye Of The Tiger is the can-do rocker about holdin’ on to your dreams, hangin’ tough and risin’ up straight to the top. Each is the equivalent of a screenplay in which obstacles are overcome by love and/or self-belief. The most successful popbusters have deliberately vague lyrics, the better to secure their place on radio playlists long after their parent film has vacated the multiplex.

My Heart Will Go On wouldn’t be such a popular choice at weddings and funerals if it dwelt on freezing to death in the North Atlantic. The Power Of Love by Huey Lewis And The News helpfully informed us that love is “tougher than diamonds, rich like cream”, but had not the faintest connection to the plot of Back To The Future. (Ray Parker Jr.’s Ghostbusters, on the other hand, is definitely about ghostbusting, and there is less call for that in everyday life.)

Musically, they care not for subtlety. Take Kenny Loggins’ quintessential type two popbuster, Danger Zone from Top Gun: synthesizers as sleek and shiny as F-14 Tomcats, guitar riffs that land like a well-choreographed strike to the solar plexus, drums like exploding trucks. It’s as if Bruckheimer had shown Loggins a shot of Tom Cruise punching the air while riding a motorbike and said, “Make it sound like that.” Ballads, meanwhile, always have a quiet, slightly sad introduction (piano is good), and a triumphant climax where it feels as if the singer might be on top of a windswept mountain, perhaps having just climbed the stairs. Their natural home is the end credits.

Soon enough, herd logic was irresistible. Whether your film concerned a karate kid, a hooker with a heart of gold or an Egyptian princess reincarnated as a shop-window dummy, the question became not, “Do we need a song?” but, “What song do we need?”

Regularly working for Bruckheimer during the ’80s, Nelson was at the heart of the popbuster machine. “Jerry Bruckheimer and Don Simpson had very strong marketing backgrounds. If anybody started that [trend], it was them. That’s what they wanted, so that’s what I would always do for them. It became part of the marketing campaign to drive people into the theatres.”

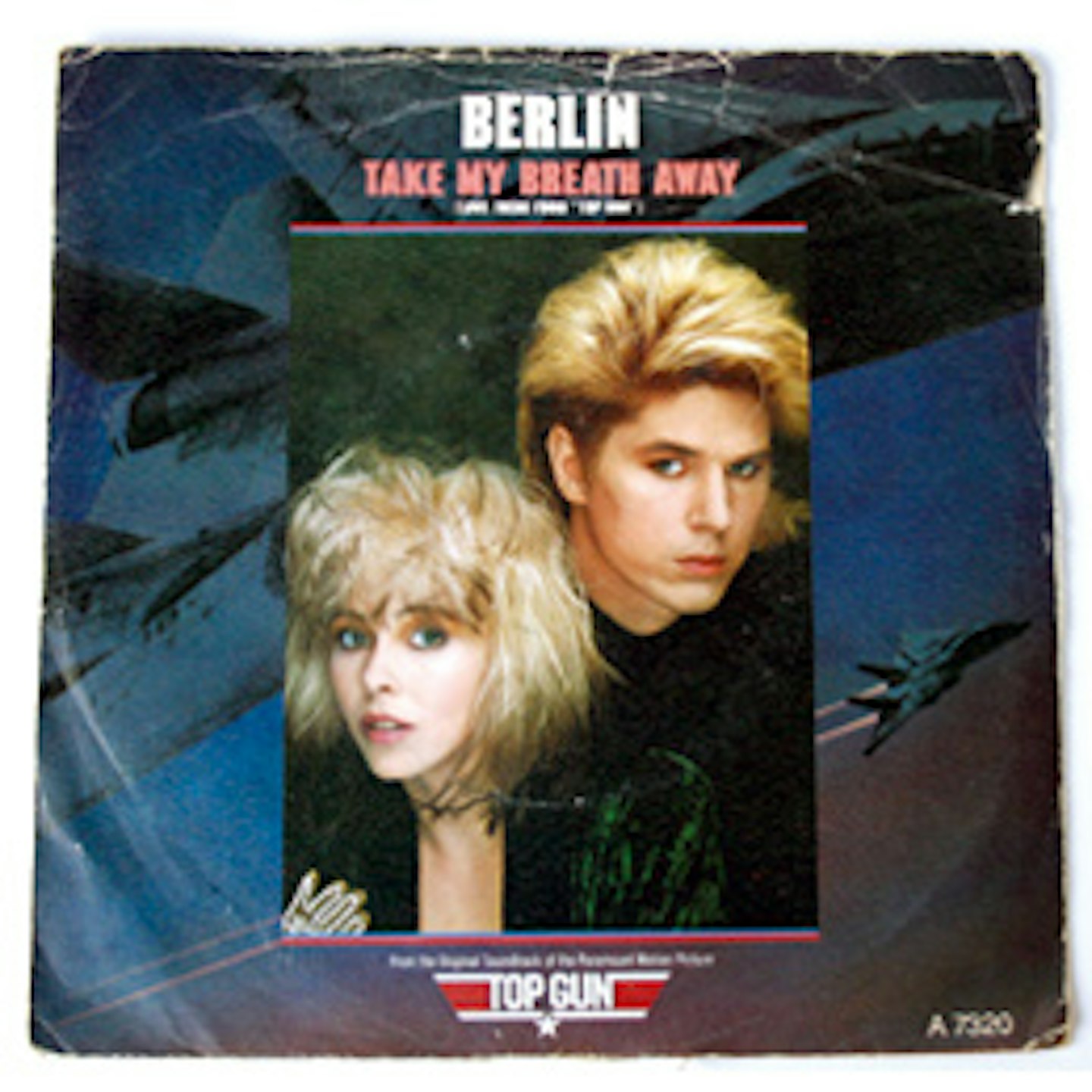

Nelson compares the process of selecting the right song and artist to casting a movie. Some songs emerged from an orchestral score: Michael Kamen, composer for Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves, wrote the music that would become (Everything I Do) I Do It For You. Others were crafted by professional hitmakers such as Giorgio Moroder (Top Gun’s Take My Breath Away) and Diane Warren (Mannequin’s Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now).

As for deciding who should sing the song, “Every situation is different,” says Nelson. “With Armageddon (Warren’s I Don’t Want To Miss A Thing), the idea of having Aerosmith came from Steven Tyler’s daughter being in the movie. When I did Phenomenon (Change The World), I wanted an artist that reminded me of John Travolta — Eric Clapton. I almost always try to imagine that this artist could have been in the movie.”

It could be a complicated process: Moroder tried out Take My Breath Away on Martha Davis of The Motels before opting for Berlin. The writers of Don’t You (Forget About Me) from The Breakfast Club offered it to Billy Idol and Bryan Ferry before Simple Minds reluctantly accepted. Kamen’s first two choices for Everything I Do were Kate Bush and Annie Lennox.

The video was then often made by the director of the movie, cutting clips from the film with suitable performance footage. This was synergy to make Simpson’s heart swell, but it could be bewildering for the musicians.

“We did a video shoot before we’d even seen the movie,” remembers Starship’s Mickey Thomas, who sang on Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now for Mannequin. “It did feel odd because the director knew exactly how he was going to piece it together, but we had no idea. So it was like, ‘Okay, at this point you’re going to get off the motorcycle and run over to this hydrant and turn the wheel.’ And I’m like, ‘Okaaaayyyy...’” He emits a rueful chuckle. “Actually, it’s not one of my favourite videos we ever did.”

BY THE MID '80S, ANY SELF-RESPECTING BLOCKBUSTER WAS UNDERDRESSED WITHOUT A TAILOR-MADE POP HIT. Big names such as Stevie Wonder, James Brown and Tina Turner took the Hollywood dollar — Bryan Adams, Rod Stewart and Sting formed a baleful alliance on All For Love for Disney’s failed 1993 reboot of The Three Musketeers — but mid-table soft-rockers were just as likely to deliver the goods. Such was the force of the trend that anyone who heard Falco’s Rock Me Amadeus could have been forgiven for thinking that even Milos Forman’s Mozart biopic had succumbed.

Sometimes the tail wagged the dog and a song eclipsed the film that spawned it. How many people who fondly remember Phil Oakey & Giorgio Moroder’s Together In Electric Dreams saw the film, a flop comedy about an amorous computer? The cross-branding hysteria reached its absurd apogee with Prince’s Batman soundtrack, whose preposterous Batdance was laden with so many dialogue samples that it was less a song than an aural trailer.

Even when the type two popbuster went the way of its makers’ mullets, the mega-ballad ruled the ’90s. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You was number one in Britain for what seemed like seven years but was in fact only 16 weeks. The Bodyguard album, featuring Whitney Houston’s gale-force assault on Dolly Parton’s I Will Always Love You, became the bestselling soundtrack of all time, winning a Grammy for album of the year. Even Britain got in the act with Wet Wet Wet’s unkillable Troggs cover Love Is All Around from Four Weddings And A Funeral. Then there was the hip-hop equivalent, with Coolio’s Gangsta’s Paradise far outperforming the teachers-in-the-’hood movie Dangerous Minds.

By%20the%20end%20of%20the%20decade,%20though,%20the%20popbuster%20was%20flagging.%20While%20I%20Don%E2%80%99t%20Wanna%20Miss%20A%20Thing%20and%20LeAnn%20Rimes%E2%80%99%20Can%E2%80%99t%20Fight%20The%20Moonlight%20(Coyote%20Ugly?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

“Back in the day, a movie like Pirates Of The Caribbean would probably have had a song at the end,” says Nelson. “Now I’m not pressured at all. On The Kingdom we went round and round thinking of song ideas and in the end we decided not to use one.”

The reason for the popbuster’s decline is primarily financial. With record sales in freefall, MTV only showing videos in the gaps between crappy reality shows and the internet transforming Hollywood’s marketing arsenal, a big song is no longer a sure-fire promotional device. During the 1980s, 19 songs from movies topped the Billboard Hot 100. In the 1990s, there were seven. So far, this decade has produced just three.

This may be bad news for Kenny Loggins, but it’s a natural correction after a period of blaring excess: a return to the days when music was designed to enhance a film rather than sell tickets. Even some of the artists who rode the popbuster wave have mixed feelings today. “It was great for us in the airplay it achieved,” says Starship’s Thomas, who still plays Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now on tour. “But when you’re a rock’n’roll band associated with a pop movie, in the eyes of some fans it diminishes your integrity. It’s kind of a double-edged sword.”

In the case of Take My Breath Away, that double-edged sword sliced Berlin in two. “Half the band was like, ‘Oh, we’re going to have to play this song for the rest of our lives now because it’s the biggest song we’ve ever had, dammit,’” singer Terri Nunn told VH1. “Take My Breath Away was one of the decisive factors in the break-up of Berlin, as well as in one of the greatest successes. So it’s really strange, isn’t it?”

Yes, the power of the popbuster is a curious thing. Makes one man weep and another man sing. Change a hawk to a little white dove. More than a feeling, that’s the power of the popbuster.

](http://www.empireonline.com/features/movie-power-ballads/p2)%20**DON'T%20YOU%20(FORGET%20ABOUT%20THEM?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

Ten popbusters that rocked the world. And possibly rolled it, too.

***Film: ***The Bodyguard, 1992

Weeks at number one: 14 (US), ten (UK)

Key moment: The eardrum-devastating climax: “IIIII will al-way-ay-ays luuuuuuuuv yooooouuuuu!”

Film: Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, 1991

Weeks at number one: seven (US), 16 (UK)

Key moment: Bryan rocking out in his wooded glade halfway through. Watch out, Robin!

Film: Rocky III, 1982

Weeks at number one: six (US), four (UK)

Key moment: The jabbing power chords during the opening seconds. Fact: the mix in the movie features real tigers growling. The single doesn’t.

Film: Flashdance, 1983

Weeks at number one: 6 (US), 0 (UK)

Key moments: The chintzy synthesizer riff. And, “First, when there’s nothing but a slow-glowing dream...” Welcome to the ’80s!

Film: Four Weddings And A Funeral, 1994

Weeks at number one: zero (US), 15 (UK)

Key moment: Marti Pellow’s ‘soulful’ improvising. “Oooh, yes it is. Oooh yeah...” Check out REM’s version{

Film: An Officer And A Gentleman, 1982

Weeks at number one: three (US), zero (UK)

Key moment: “... Where the eagles fly, on a mountain high.” Again with the mountains.

Film: Armageddon, 1997

Weeks at number one: four (US), zero (UK)

Key moment: The way the drums crash in like an asteroid the size of Texas. Written originally for Celine Dion.

Film: Mannequin, 1987

Weeks at number one: two (US), four (UK)

Key moment: Glace Slick, the singer of Jefferson Airplane’s classic White Rabbit, pretending to be a mannequin in the video.

Film: Titanic, 1998

Weeks at number one: two (US), two (UK)

Key moment: The iceberg-proportioned final chorus. James Cameron originally didn’t want a ballad, claiming Schindler’s List never had a song in it.

Film: Top Gun, 1986

Weeks at number one: one (US), four (UK)

Key moment: The sight of Terri Nunn, decked out in blue overalls and with two-tone hair-a-blowing, singing on top of a fighter jet in the desert.