James Cameron’s Titanic was, of course, an enormous success, the highest-grossing film of all time until the same director’s next feature smashed its record. But its production was a famously difficult and complex one, a shoot on an almost unprecedented scale which featured tough technical challenges and which was overseen by a director who knew exactly what he wanted and who demanded the utmost from everyone until he got it. Oh sure, there’s a happy ending: eleven Oscars and nearly $2 billion at the box office. But it was a tough journey to get there – and here is the first-hand account of those who made it...

The feature first appeared in issue 274 of Empire magazine. __Subscribe to Empire{

Two-and-a-half miles beneath the waves of the North Atlantic, it began to dawn on James Cameron that something was wrong. Peering through the tiny porthole of Russian minisub Mir 1, he could hear the insistent ‘ping’ of the sonar accelerating alarmingly. Suddenly, a cliff face of rusting steel, studded with rivets the size of a breakfast grapefruit, emerged from the gloom. He realised the sub was about to collide with the hull of the Titanic. Such a collision, he knew, could crack the lens of the camera pointed at the wreck and, under 1.1 million pounds of pressure, send a high-speed tsunami of seawater blasting down the camera’s titanium cylinder into the shell of the sub, killing him and his crew in an instant. (For good reason, the cylinder had been nicknamed The Cannon.) To avert catastrophe, Cameron attempted to deflect the blow with the camera’s pan and tilt controls, aiming the lens away from the hull. The controls froze, as they were wont to do if turned too fast. With superhuman self-possession, Cameron adjusted the mechanism’s gain control and, as disaster loomed in his window, forced himself to turn the controls as slowly as possible. The camera gradually swung away, crashing into the wreck at a 45-degree angle. “I tense for the thunder crack of implosion,” Cameron later wrote in his diary. “Lights out in 2/10,000ths of a second.” It didn’t come. He had done just enough for the camera housing, which sheared off and disappeared, to absorb the impact.

“It was very exciting, but also very worrying,” says producer Jon Landau who, at the time, was aboard the Russian dive ship Mstislav Keldysh, blissfully unaware of the drama going on below him.

It’s stories like these that form the Titanic legend, of James Cameron’s staggeringly ambitious plan to tell the tale of the most infamous maritime disaster in history through the prism of lavish romantic drama, an undertaking that required building an entire studio and the largest standing set of all time, and which entailed a shoot of such prolonged, budget-busting complexity, physical endurance and emotional intensity it put previous cinematic behemoths — the Waterworlds, the Cleopatras, the Heaven’s Gates — to shame.

But as compelling as Cameron’s death-defying antics certainly are — his relentless, uncompromising quest to bring his vision to the screen — they do not paint the whole picture. Titanic was born from the labours of an army of actors, technicians, craftsmen and artists who all, under Cameron’s command, with imminent disaster often looming in their own particular windows, rose to the occasion with ingenuity, fortitude and unshakeable belief in the project. Costumer Deborah Scott is a case in point.

In preparation for the most challenging job of her career, Scott spent months researching every available scrap of information on how people dressed in 1912, poring over newspapers, magazines, catalogues, personal journals and archives, including that of the White Star Line. So intensive was her research, it often surprised even her.

“I couldn’t believe how many birds were killed just to adorn women’s hats,” she exclaims, “I mean, hundreds of thousands!” She also scoured the globe to amass a museum’s-worth of original pieces, ensuring more than 60 per cent of costumes seen in the film were from the Edwardian era. Scott’s search might not have sent her to the depths of the ocean, but it was, for a costumer, as close to revisiting Titanic as you can get. And it had its own moments of drama.

“I remember one day,” she says, “there was a group of really fancily dressed people in a lifeboat, all wearing original clothes: gloves, shoes, jewellery, everything. And Jim decided he wanted more people in the water, so he just dumped them in! There was shock and horror among the costume crew. I almost had a heart attack. This was the first week and I was thinking, ‘Is this how it’s going to be?!’ When Jim demands something, you’ve got to give it to him. But it was a bad day for us and we had to decide how we were going to handle it. You just keep on sewing,” she laughs. “We knew at the end everyone was going to be in the water so it was a race against time.”

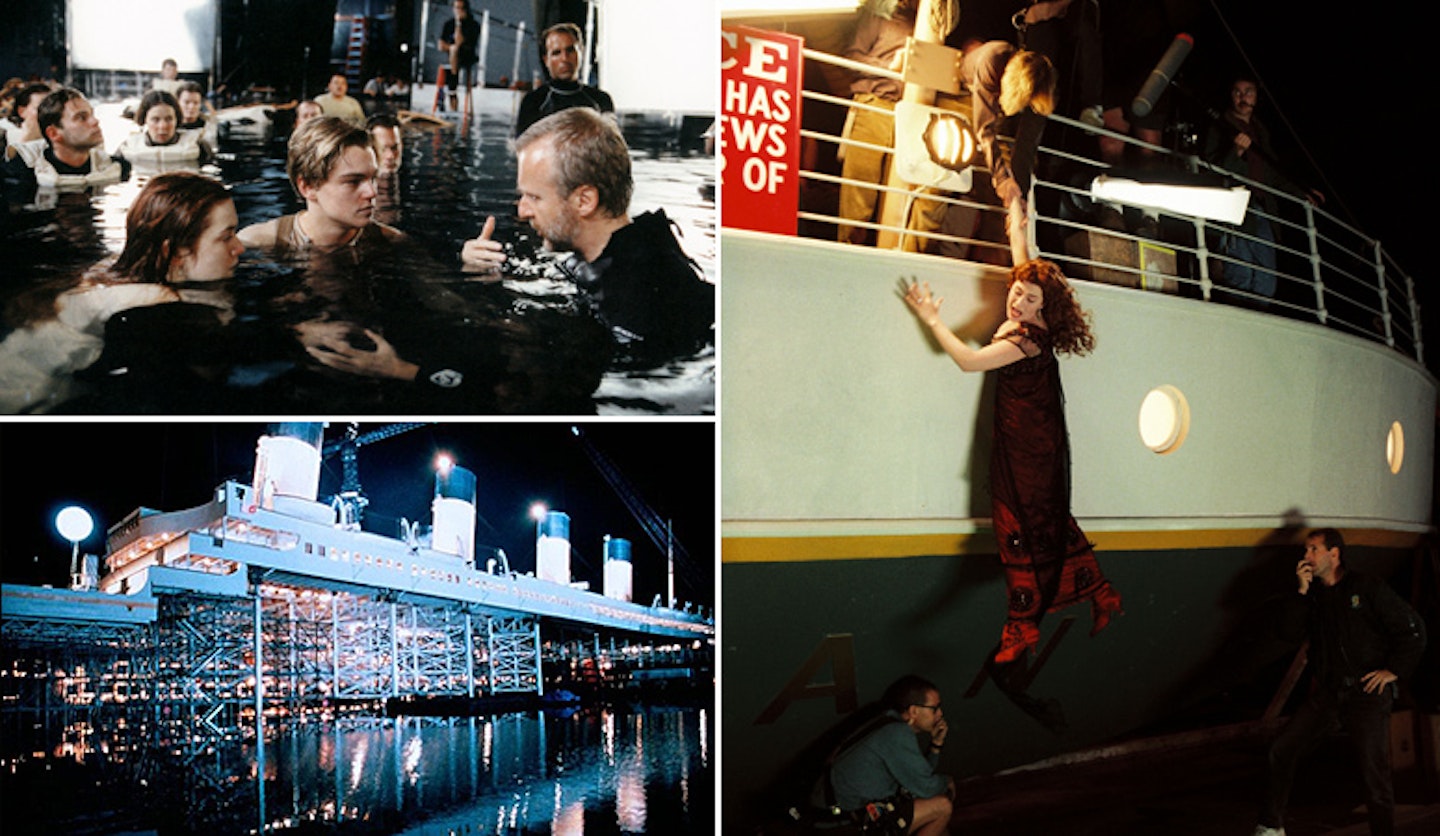

(Clockwise from top left) Cameron, Winslet and DiCaprio get wet. Winslet hangs out on set. The massive Titanic model built for the shoot.

For most members of the cast and crew, Titanic began in earnest when they arrived in Rosarito, the shabby beach resort on Mexico’s Baja California peninsula chosen as the site for the studio complex, vast water tanks and ten-storey-high, 775-foot-long ‘Big Boat’ set that would accommodate the shoot. Often cited as symbolic of the production’s excess, the studio was, according to Landau, a huge money-saver, providing almost everything Cameron and his crew needed on site. Nevertheless, it was a monumental undertaking. First Assistant Director Josh McLaglen remembers his first visit to Rosarito. “Jim and I drove down to what was then a vacant lot. We bought a model of Titanic in the back of a pickup, carried it out and set it up on two sawhorses. Then Jim started studying the elements. He triangulated the light, the solstice of the sun, the wind direction, the position of the ship, how close it would have to be to the cliffs so we could see the ocean. It was incredible, watching him envision everything we needed to do to pull the movie off.” Later arrivals were no less impressed.

“It was awe-inspiring,” recalls Billy Zane (who played Cal Hockley, Kate Winslet’s villainous fiancé). “They’d built an entire city to make a film! When I showed up there were three tower cranes spinning against the skyline and thousands of employees milling about. It was like the glory days of the studios: Cecil B. DeMille, MGM. And getting off the freight elevator at the upper deck, you felt the heft of the bannisters, the metal railings, the weight of the doors and you thought, ‘This is tangible, this is solid.’ It was like being there on the Titanic. It was a truly immersive experience.” He laughs at his no-pun-intended pun. “Nothing could have prepared you for the sheer logistics of it.”

Director of photography Russell Carpenter was brought in after original DP Caleb Deschanel was fired over ‘creative differences’. He recalls his brief from Cameron. “He said, ‘Well, you know how these films are supposed to look.’ That was it! I was on another film so I was only able to get down at weekends to see what was happening. It was literally like witnessing the Gold Rush, buildings were going up that fast.”

Did I ever think, ‘What the hell have I got myself into? Hell, yes!

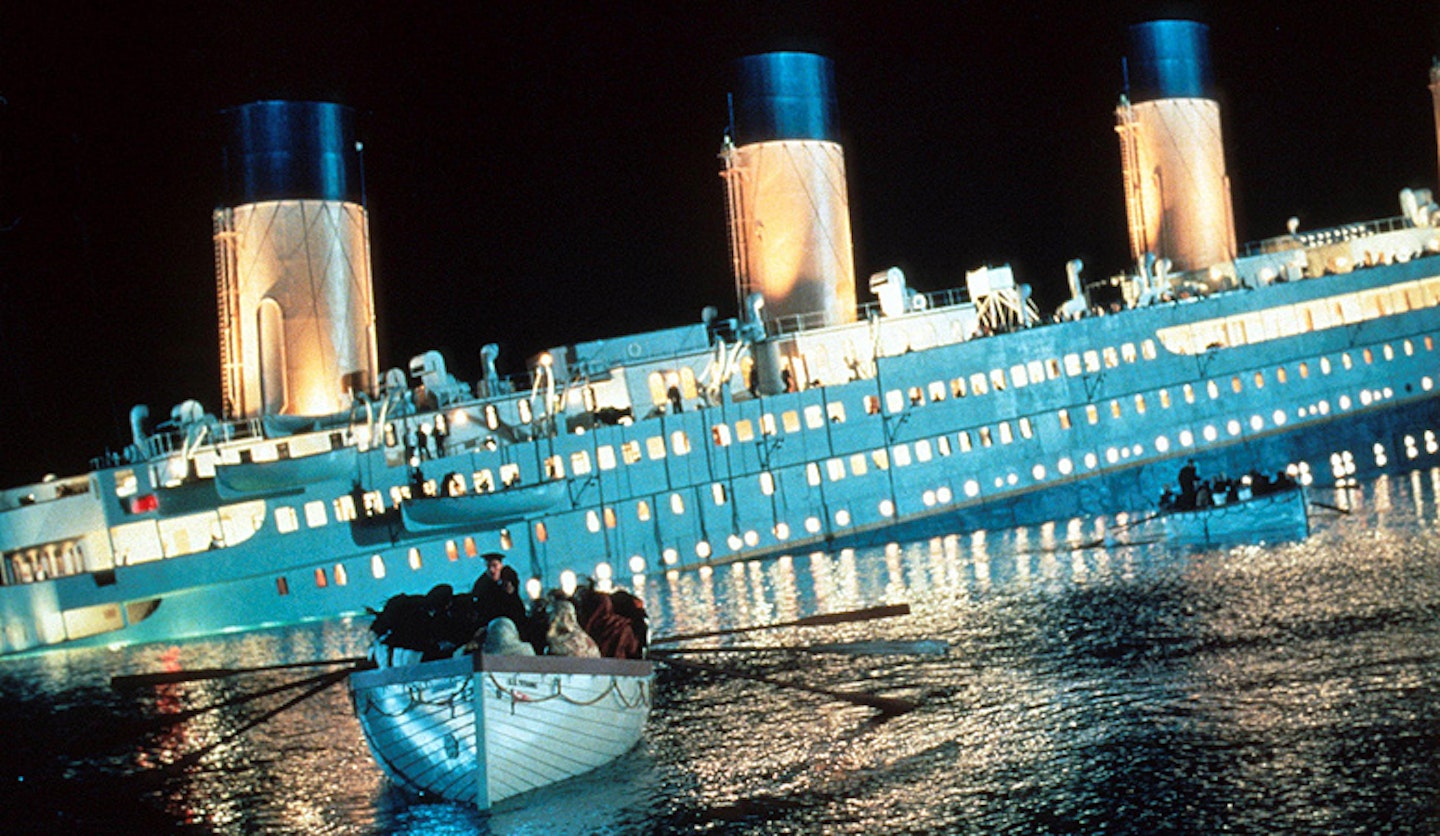

Jon Landau “Did I ever think, ‘What the hell have I got myself into?’” laughs Landau. “Hell, yes! But then I’d drive over the hill and see that ship, just dominating the coastline...”With footage from the wreck and the modern-day sequences in the can, Cameron and his crew began shooting coverage on stages at Rosarito and in tanks near San Diego. Construction on the Big Boat was, inevitably, running over schedule. “We were shooting underwater shots,” says McLaglen, “buying time while the set was built. It was like a skyscraper going up.” It was, given that skyscrapers have been built before, more problematic than that. The Big Boat was an unprecedented feat of engineering. And nothing, to echo Billy Zane, could have prepared its makers for the sheer logistics of the thing. To effect the sinking, the ship was constructed in sections, each controlled by massive hydraulic risers. “The sinking process,” says McLaglen, “took it from three degrees, then to six degrees. The forward section had a riser allowing it to sink 30 feet. The poop deck could go from zero to 90 degrees, all the way from level to 12 o’clock. That was really hair-raising.” What was no less hair-raising, particularly to 20th Century Fox, was the cost. Almost the moment ground was broken at Rosarito it became obvious that the original $110 million budget would not begin to cover it. Tensions between the studio — which partnered up with another major, Paramount — and the filmmakers began to rise. Meanwhile, the challenges of filming on a set the length of two football pitches and the height of an office block were becoming apparent.

“The enormity of it was overwhelming,” says Carpenter. “So much of what we did would now be done in the computer. But with Titanic, when you see the 800-foot ship, it’s an 800-foot ship; when you see 500 extras running along the deck, it’s 500 extras. The difficulty of capturing that, getting the cameras set up, was an enormous challenge.”

Aside from the groundbreaking CG work done by Digital Domain, most of Titanic’s epic effects were achieved mechanically. Again, a colossal and unprecedented venture.

“I think everyone on the handshake deal Jim and Jon made with Fox knew it was going to be big,” says McLaglen. “And Jim pitched it honestly. He said, ‘I’m going to make the best version of this movie possible, and you’re going to see it all in-camera.’ I’d say 85 per cent of what you see in Titanic was done in-camera.” And given what you do see, the RMS Titanic breaking apart and sinking before your eyes, that’s mind-boggling. “And a lot of stuff just didn’t pan out,” says Carpenter. “There was a scene in steerage where the ship’s sinking and Kate and Leo are looking for a way out. They see a man holding his child. And what was supposed to happen was a wall of water exploding through a door and washing them away. There were tons of water, but for some reason it looked like your washing machine had overflowed. It had to be re-shot, and with Jim if Plan A doesn’t work, Plan B is going to be a lot more challenging. It’s never a retreat. We feared Plan B.” In this case, Plan B was to recreate the set-up outside on the lot and pound it with triple the amount of water, cascading from elevated dump tanks and smashing the impromptu set to matchwood. The move shocked even Cameron’s key crew members. It was a scene Fox had insisted he cut.

Cameron’s alleged excesses were soon leaked to the media, who began gleefully reporting that the shoot was out of control. The piquancy of the title was seized on mercilessly: Titanic was going down, taking Jim Cameron and an unrecoupable amount of studio money with it. Rumours abounded that the production was on the brink of being shuttered and Cameron summarily fired. “That was never an option,” counters Landau. “And I think that’s what frustrated [Fox] the most. When you sign on for a Jim Cameron film, you get Jim Cameron.” Still, asked whether Cameron’s extravagance, his legendary perfectionism and refusal to compromise contributed to spiralling costs — as press reports insisted at the time — he admits to a grain of truth. “But [the press] weren’t seeing what we were seeing,” he adds. “We knew we were making something magical.”

The press weren’t seeing what we were seeing. We knew we were making something magical.

James Cameron “Jim was never extravagant,” says McLaglen. “If he incurred more time and expense, it was because he corrected something that needed correcting. Everything’s planned out, but shit happens. You break a manifold or a hydraulic line, or the computer’s not sinking the set at the correct rate, making it unsafe. How many people build a house budgeted at a million dollars and when it’s done, it’s a million-three? The builder says, ‘Well, we tried to anticipate everything but something came up and we had to fix it.’ That’s what happened to us.”With a potential final cost of over $200 million — an astronomical amount, even by Cameron standards — the Fox-Paramount partnership quickly soured. Fearing the studio’s investment stood no hope of seeing a return, Paramount insisted it be capped at $65 million, leaving Fox to pick up the tab for any subsequent overages. The deal, struck by then-Fox studio chief Peter Chernin, was described as “one of the better deals since the Indians sold Manhattan”. Such is the benefit of hindsight. At the time, no-one expected Titanic to make a penny and a grim mood of damage control set in at Fox. “I remember talking to Jim when everything in the press was about what a disaster it was and he said, ‘Well, I guess after this I have to go make something profitable. This’ll be my art film.’”

Tired of beating Cameron with his own tattered schedule and ballooning balance sheet, the press found another bone to chew on: the conditions on set and how Cameron, apparently a Colonel Kurtz figure plunging ahead up a river of no return, was driving his cast and crew to exhaustion and beyond, sacrificing their health and safety to his doomed grand folly. “There is no-one Jim demands more of than himself,” says Landau. “And when you’re working with an army, you need a general. Jim is a general.”

“Of course we worked long days,” says Carpenter, “but that’s not unusual. The hard thing was working long days in water, just moving around in water, how slow and exhausting that is. At the end of the day, everyone was ready to collapse.” Not surprisingly, water was the source of most discomfort — and a genuine safety concern. “We hired about 20 lifeguards from San Diego,” says McLaglen. “Each lifeguard was responsible for ten people. The big tank was only three-and-a-half feet deep, but it was absolutely freezing. We were pulling people out on the verge of hypothermia.”

“I wisely decided that Cal would never get wet,” chortles Billy Zane. “He’d step on people’s heads like a cat before he’d let that happen. I managed to convince Jim it was in character — you’ve got a thousand people soaking wet and only this asshole doesn’t get a drop on him. Very sly, but boy was it practical.”

Zane also has a slightly less charitable take on the hardships than those further down the credit list. “Were people unhappy because they were cold and wet?” he says. “What movie did they think we were making? It was hard, of course it was hard. But remove the obvious and the whinging and get on with the work. No small task, and everyone went above and beyond. Still, there was a lot of belly-aching. Did stuntmen get hurt? Did someone not get enough sleep? It’s not for me to say. But I’m with Patton in the sick ward on this one.”

That said, not even Zane would deny that Cameron can be — how to put this politely? — a hard task master, and it was a rare crew-member indeed who did not, at some point, feel the rough edge of his tongue.

(Clockwise from left) Cameron keeps a close eye on leads Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet. DiCaprio and Winslet in the famous scene. Billy Zane as Caledon 'Cal' Hockley.

“Jim can be very intimidating,” allows Deborah Scott. She recalls one instance where she had designed a magnificent hat for Kate Winslet. “We were shooting a scene where Kate comes out of a tea party having decided that she’s had it with this life,” she says. “She tears her hat off and throws it into the water. We shot the exterior on the giant set. We were all way over on one side of the boat and Kate was on the other. She came out and Jim decided he did not like her hat at all. The whole set froze while he ran from one side of the ship to the other, ripped it off her head and threw it into the water himself.” To Scott, watching another irreplaceable creation hit the briny must have been the equivalent of seeing a million-dollar deep-sea camera crash into the wreckage of the Titanic and float away.

“Jim’s biggest concern was contingency,” says Zane. “Meaning, if the third gun jams and the sun’s coming up and to not get the shot costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, and the fourth gun is down the elevator, across the lot sitting in a truck for some stupid reason, you’re going to get your ass chewed. Or you’re going to get fired. Was James hard on people? He was hard on people who weren’t doing their job.”

Ultimately, though, despite the bruised egos, skinned knees and water-shrivelled extremities (albeit with the benefit of hindsight, a boatload of Oscars and a box-office haul approaching the national debt of Greece), most people’s memories of Titanic are of the once-in-a-lifetime, cherish-to-the-grave variety. And most reflect both the agony and the ecstasy.

Was James hard on people? He was hard on people who weren’t doing their job.

Billy Zane For Russell Carpenter, the moment that sums up Titanic for him was the scene where several tons of water crash through the glass dome of the first class salon, pummelling a crowd of stuntpeople and obliterating the solid oak staircase. Needless to say, a second take would have been on the costly side. Carpenter and his gaffer spent days preparing the set-up. For safety reasons the dome was, in fact, made of paraffin, which meant only a single light could be placed on it. On Cameron’s command, water thundered through the set with such force, it tripped the safety back-up and shut out all the lights.“It was absolute chaos!” says Carpenter. “You couldn’t see a thing. When the water dissipated I looked up and the only light left on was the bulb in the dome.” A reporter described Cameron viewing the playback as “like a man studying the smallprint in his contract with the devil”.

“I thought, ‘Okay, I’m going to kill myself,’” says Carpenter. “I couldn’t run away to Mexico; I was already there.” By some miracle, however, the plucky lone bulb lit the scene perfectly. “But I didn’t know that,” Carpenter laughs. “I had to sweat it out ’til I saw the dailies the next day.”

“I remember sitting in a hot tub on set with Jim,” says Billy Zane. “Me in my tuxedo, Jim in a wetsuit, someone randomly handing me a hotdog. I had to chuckle. We were beyond reason, beyond logic. That’s when I knew we were in the zone. I thought, ‘My God, we must be making something special.’”

“What sums it up for me,” says Josh McLaglen, “was Jim on the tower crane. He’s got 2,000 extras on three decks, running for their lives, and he picks out Kate and Leo. A masterpiece of choreography. It felt like you were right there, at the scene. It epitomised the scope and spectacle of the movie, and the horror and emotion of the real event.”

“When we wrapped the last scene,” says Jon Landau, “water crashing onto the bridge and Captain Smith going down with his ship, I called my wife. I said, ‘We did it. And no-one died.’”