This article was first published in Empire Magazine Issue #50 (August 1993).

It's big, it's made tons of bucks and it'll chew your head off if you don't watch out. Empire visits the set of Spielberg's awesome dinosaur fantasy.

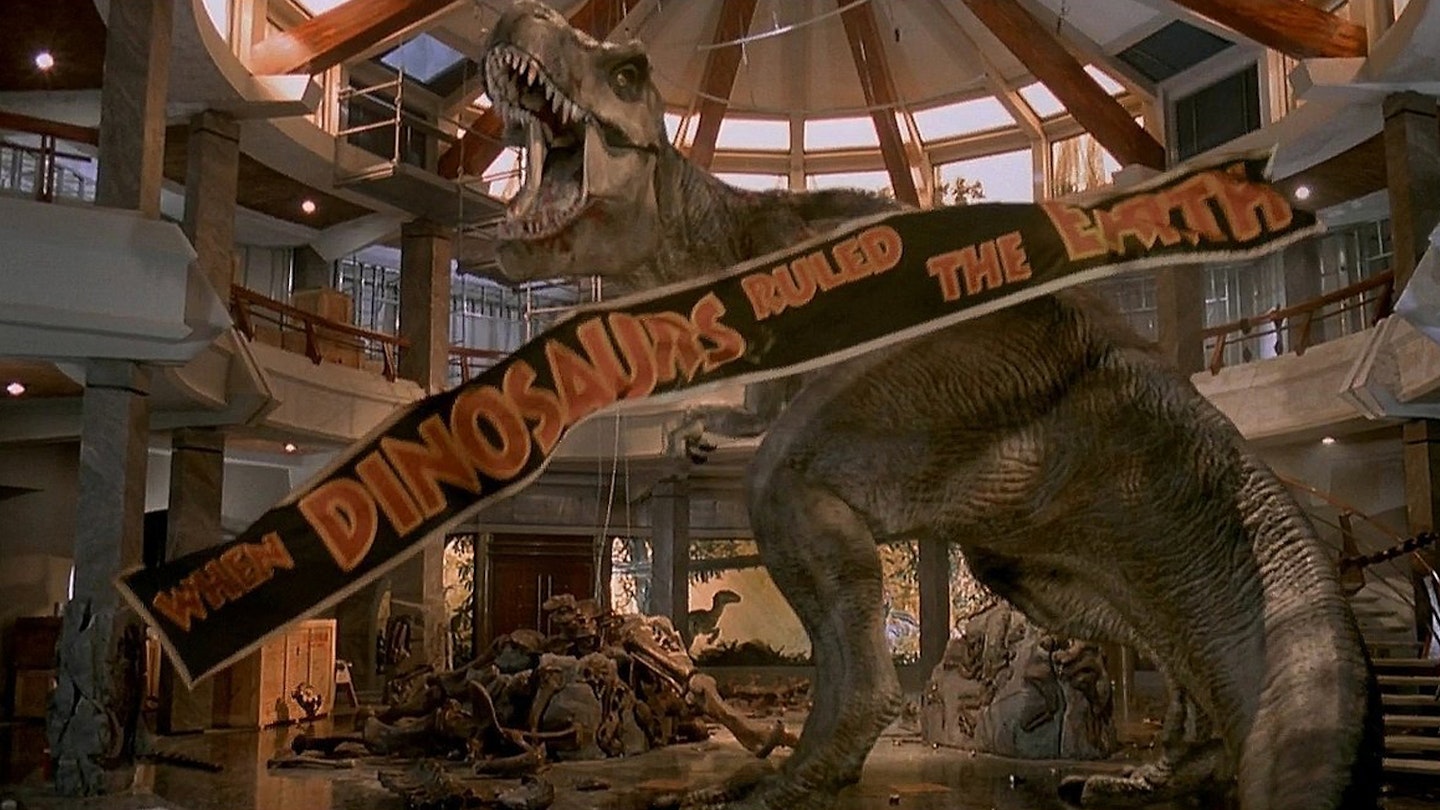

It took more money in its first weekend than any film in history. After nine days it had sailed past the $100 million mark. And very shortly it will almost certainly nab the title of Biggest Grosser Of All Time from that other little Steven Spielberg film, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. Rufus Sears joins the director, his cast and his ludicrously lifelike dinosaurs on the set of the already-legendary Jurassic Park...

During the pre-production of Jurassic Park, Dr. Jeffrey Laurence – possibly the world's leading AIDS researcher – received a call at his laboratory in New York City. It was a representative from Steven Spielberg's Amblin Entertainment saying they were preparing to produce a screen adaptation of Michael Crichton's best-selling novel, Jurassic Park, and could they come and have a look at his lab? Clearly expecting something special from a man working at the very forefront of medical science, the entourage that arrived the very next day from Los Angeles were deeply disappointed with the room they were ushered into.

"Where are the lights, where are the buttons?" they asked, gazing, around Laurence's workaday lab. "Steven's not going to like this."

And, sure enough, Steven didn't like it, opting instead to create his dino-labs from scratch with just his imagination – and that of production designer Rick Carter – as a blueprint. When you're making a movie like Jurassic Park, reality is very rarely good enough – as a rule, you are required to improve on it. And improve on it Spielberg and his huge team of specialist colleagues most certainly did...

Had E.T. made no money, I might have been permitted to delve into The Colour Purple and Empire Of The Sun with a little more respect. – Steven Spielberg

"The sickle claw of a velociraptor," says Steven Spielberg quietly. We are standing on the Universal Pictures soundstage knee-deep in jungle weeds that are hiding trap doors and pits full of cameras, cables and hydraulic platforms, and Steven Spielberg is doing what he does best: waiting patiently while his veteran crew hasten to show him what they know he wants to see. As he watches the readying of a disturbingly lifelike replica of a dinosaur, he turns the claw – dark brown and glowing dully under the studio lights – over and over in his hands. It is a fossil, recently discovered and acquired by Spielberg. God knows how. When you're Steven Spielberg, you get to keep such trinkets in your trouser pockets.

"Sixty-five million years," he says, almost privately. Then, suddenly, the spotlights flick on around him and he's fully back on the job, back to the business of resurrecting his reputation as the world's most copper-bottomed director convincing Universal Pictures' parent company MCA that they should reverse their plans to ease off on moviemaking; producing the most gob-smacking special effects ever seen on film; and possibly, just possibly, creating a box office blockbuster to rival Raiders Of The Lost Ark, Jaws or even E.T.

"I don't care about those things," counters Spielberg when presented with the very real possibility that Jurassic Park could ease in above Spielberg's three other films currently residing in the list of the Ten Biggest Grossing Movies Of All Time. "Because I hear those discussions every summer and every Christmas, whether I have a film in the marketplace or not. I've had my fair share of first place, and I would be awfully greedy if I said to you right now, 'Yeah, I'd like to be the biggest film of the year.'"

Greedy or not, Steven Spielberg would seem to have that particular position in the box office charts signed and sealed, if not quite delivered, with Jurassic Park taking an astonishing $120 million in its first ten days on release in the US. The casual success of the man is awesome: for much of Jurassic's vital post-production, he was flitting between Poland and Paris, where he had already begun shooting his labour-of-love Schindler's List, a black-and-white homage to Oskar Schindler, a Polish doctor who saved thousands of Jews from Nazi death camps.

"I'm sitting here working in a black-and-white medium on a Holocaust story about an unpraised hero, over my head in that kind of sorrow every day," recalls Spielberg, after Jurassic Park is wrapped and ready to go. "Then I have to kind of shift gears and get on the action-adventure story fast track. That's been hard on all of us – the same editors have cut both movies along with me – so together we've gone through a kind of cinematic and cultural whiplash..."

Just as Schindler's List is cousin to The Colour Purple and Empire Of The Sun – Spielberg's more personal films that probe what reviewers like to call The Human Spirit – Jurassic Park finds its Spielbergian forerunners in Jaws, E.T. and the Indiana Jones series, films that effortlessly entered the record books as among the biggest-grossers of all time. Indeed, Spielberg must be the only filmmaker a studio would bet its entire future on. TriStar did it last year with Hook, and the $280 million that film earned worldwide preserved production chief Mike Medavoy's job and rebuked those who had predicted it wouldn't recoup its high production costs (the US take alone did that). The reviews (of which Spielberg had said in anticipation "I don't pay much attention to them") were decidedly mixed, of course, and Medavoy, who was Spielberg's first agent when the wunderkind was just 18, looked a tad hyberbolic when he said, just before Hook's release, that "this is his real shot at Oscar."

Indeed, the "Oscar thing" is a scab Spielberg nowadays declines to pick. He's made films that have earned up to a dozen Oscar nominations (notably The Colour Purple, which finally came away empty handed), and he's even been nominated (for Close Encounters, Raiders Of The Lost Ark and E.T.) but has never actually won a Best Director's statuette.

"I guess I have to live with that because it's what I cut out for myself at the beginning of my filmmaking," he says of his conspicuously unadorned mantelpiece. "I made these movies that were perceived to be big. I thought Close Encounters was very personal, and E.T., which is the smallest, most personal movie I've ever made, was perceived to be big only because of how much money it raked in. Had E.T. made no money, if it hadn't been a blockbuster, I might have been permitted to delve into The Colour Purple and Empire Of The Sun with a little more respect."

Steven Spielberg came up through the ranks, of course, with the Movie Brats, though the critics never considered him to be in the same club as those early 70s director-auteurs. Of his sometime peers, Coppola remains a valuable maverick; George Lucas has left directing for the creative/business pasture of his Industrial Light And Magic special effects company; Brian De Palma is struggling to come back from the debacle of Bonfire Of The Vanities; and the best of them all, Martin Scorsese, remains a valued, if envied, friend.

It was so obviously a Spielberg film... extraordinary things happening to ordinary people. – Kathleen Kennedy

When Spielberg passed his production of Cape Fear to Scorsese – "I developed the script, then I hired Bobby De Niro, and then I asked Marty if he'd direct it" – he staged a reading with De Niro to persuade Scorsese to do it. But as soon as Scorsese agreed, "I just stepped off the project, and said 'See you later.' My sensibilities are 180 degrees in the other direction. I think Marty is the best American filmmaker working today, but because I'm nothing like Marty, it would be really pretentious for me to produce him. That way we can remain friends forever. Marty looks at my movies and says, 'I couldn't do that,' and I look at his movies and say, 'I couldn't do that.'"

Despite this admission, Spielberg smarts at the suggestion – leveled at him for years over the formulaic nature of some of his movies – that he is a one-dimensional filmmaker.

"Everybody thinks I just studied David Lean," he complains. "I was seeing everything Fellini or Antonioni put out five or six times over. But there's a whole generation moving in behind our generation – the true technocrats have come in. We're the last generation who learned movies from movies. This new generation has learned movies from TV and MTV – bombarding you with 18-frame cuts."

There's been precious little talk of Oscar here on the set of Jurassic Park – in fact, the movie's entire raison d'etre is at the other end of the scale. Spielberg is well aware that Universal chief Tom Pollock is as much at risk as Medavoy was over Hook, and that the film can be seen as merely the largest plank in a massive merchandising effort that embraces Universal's two theme parks and over 100 licencees turning out 1,000 separate merchandising spin-offs, from t-shirts to computer software. McDonald's and a host of licencees are spending some $68 million on advertising its Jurassic Park tie-ins. Indeed, Pollock's boss – and Spielberg's original mentor – is MCA president Sidney Sheinberg, who told the Wall Street Journal that, "if this is just your garden-variety summer movie, then we're pretty stupid – I'm putting my neck on the line here."

With MCA's Japanese parent company Matsushita – the ultimate owners of Universal – uneasy about their heavy film investment, Sheinberg's not kidding, although comfort may be gleaned from a couple of previous collaborations between the Jurassic players: it was Universal working with Spielberg that brought us both Jaws and E.T.. And it was Universal – in collaboration with longtime Spielberg producer (now at Paramount Pictures), Kathleen Kennedy – who saw the sense in purchasing the rights to Michael Crichton's novel about a theme park full of genetically engineered dinosaurs gone mad.

"It was one of those projects that was so obviously a Steven Spielberg film," points out Kennedy. "He is very often interested in the theme of extraordinary things happening to ordinary people." Throw in a couple of wide-eyed kids, the Spielberg theme of powerful forces out of our control as science goes horribly wrong, and the promise of a good out-of- your-seat fright, and the deal was struck. Universal paid Crichton $2 million for the film rights and a first-draft screenplay before his novel was even published...

"Jurassic Park is a place where the dinosaurs are knocking out a living for themselves," says Steven Spielberg, back on the Universal soundstage. "And they simply regard man as a sort of cohabitant to either coexist with peacefully or to be pursued as prey." Spielberg, though of average physical dimensions and humbly uniformed in the baseball cap and blue jeans of a dues-paying crew member, still seems like a throwback to the days of capital-D Directors – the megaphone-and-monocle types who would move armies of extras with a toss of their arm. What makes him seem that way is his utter devotion to what his cameras (and ultimately, those wonderful people in the dark) are seeing. Others are better at luring stars out of their trailers, or sweeping on to the set firing off instructions right and left. What Spielberg is best at is understanding deeply the processes of filmmaking.

"Every single action sequence on this movie was storyboarded almost two years before we ever shot scenes," he says, as he prepares for the re-enactment of a tropical rainstorm courtesy of 50 pipes hanging above him. "I didn't want to go off those storyboards, and they became gospel. Everybody planned accordingly. I think that's why we're able to do this picture ahead of schedule."

Standing happily among the filmmaking machinery in his yellow rain gear (the camera's been fitted with its own protection, a spinning glass disc that flicks the drops away from the lens), Spielberg asks for one more rehearsal of a 'raptor hop.

This movie is not Alien, where they can take whatever form your imagination suggests. These are dinosaurs that every kid in the world knows. – Steven Spielberg

Velociraptor, that is, a fitting name for the speedy, six-foot tall feeding machines that are, in the final analysis, even more terrifying than the film's first star villain, a tree-tall tyrannosaurus rex. For this shot, the camera will see it only as a foreground blur, stamping rapidly across the frame while one of the film's characters busies himself in the background.

Though we see the actors agape at the sight of various dinosaurs, the extinct beasts are often treated with the studiousness of a nature documentary. They will not be seen as wavering shapes coming forth from an astral glow, as the beasties were in the director's E.T.: The Extra- Terrestrial and Close Encounters.

I'm going for total realism," announces Spielberg, "as opposed to anything that hypes the wonder. There are no lights around my dinosaurs, they're in the flesh, walking around in broad daylight, right in front of you, making no excuses for themselves. They're as close to living animals as any I've ever done."

Spielberg pauses.

"This movie is not Alien, where they can take whatever form your imagination suggests and be anything you want them to be because they don't exist in history or physiology," he says. "These are dinosaurs that every kid in the world knows."

Spielberg casts an approving eye over the lizard-skinned raptor before him. "Most of our dinosaurs were shot full size," he says. "Stan Winston built them for us in his creature shop – which we refuse to call it, we call it his 'animal shop'."

Today's work is with the almost hyper-realistic models, with their intricately cabled eyes, mouths, and limbs. As soon as Spielberg gets his raptor hop, he has to turn to a thorny shot of a baby 'spitter', or Dilophosaurus.

"He's the only creature that hasn't worked too well," muses Spielberg. "We had tremendous success with the T-rex, triceratops, the 'raptors, but when we came to the little spitter which I always anticipated would be the easiest dinosaur of all..." Spielberg shrugs. He knows he'll get a second crack in the editing room.

When it comes to the human participants, Crichton and Spielberg have given great thought to exactly how they come across. The palaeontologist Alan Grant (Sam Neill) and his colleague and girlfriend. Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern) have a liking for the dinosaurs, and mathematician Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) has a sense that the natural order has been wrongly and fatally disrupted. But aside from two children visiting the island (Tim and his sister Lex, played by child actors), and the contradictory figure of John Hammond (Richard Attenborough), often the lower-billed humans seem fair game.

"That's why this film is more like Ten Little Indians than it is like Godzilla attacking Tokyo," says Spielberg. "The minute their helicopter lands on the island, they aren't safe. I mean, they're dealing with an animal that's been extinct for 65 million years, and to be presumptuous enough to think they are safe in Jurassic Park is the reason they deserve to be eliminated one after the other. There's a presumption in this genre that the more invasive the people in an environment are, the more ill-equipped they are to survive it, and the more the audience feels they deserve what's coming."

"The first scene, you'll be jerked around a little bit, out of your seat, and get pretty alarmed," says Spielberg of the film's structure. "And then it goes back to Montana, a normal summer day digging for velociraptors, and we sort of go back three steps and tell the story."

Spielberg pushed screenplay collaborators Crichton and David Koepp (Death Becomes Her) to preserve this structure – a structure that has lead critics to complain that you have to wait an hour for any decent action – and, partly because he had his hands full directing Schindler's List in Poland, never previewed the film.

"I don't need a preview to tell me if a movie's too long or too short," he says. "I already know it's too long for the first 45 minutes. There's nothing I can do about it, because I feel it's important to give some of the background in terms of chaos theory and DNA cloning – to set the stage for the audience so they won't have to think about it during the second half of the film, but they'll believe it even more..."

There's a whole generation moving in behind our generation – the true technocrats have come in. – Steven Spielberg

Jurassic Park's storyline has been much talked of already. Ageing entrepreneur John Hammond has financed the "bio-engineering" of actual dinosaur DNA (trapped in blood-sucking insect bodies, preserved in amber) into living creatures, and set up a theme park on an island off Costa Rica. The initially reluctant Grant and Sattler, as well as rogue mathematician Malcolm, are hired to size the park up for Hammond's investors. They arrive, meet the skeleton staff, and start on what's billed as a typical, preview park visit. As the spanner-in-the-works Dennis Nedry (played by Wayne Knight, the fatty cop from Basic Instinct who was cast first by Spielberg after seeing that movie – "I waited for the credits to roll and wrote his name down") shuts down the very computer systems he's designed to run the park, all hell breaks loose.

"John Hammond has Walt Disney's vision of Utopia for children all over the world, except it doesn't turn out to be Utopia – it's not the petting zoo he thought it was going to be," says Steven Spielberg. "I felt Hammond was a brilliantly written, but patented villain, and I was much more interested in portraying Hammond as a cross between Wait Disney and Ross Perot. Attenborough sort of keeps you off balance, second-guessing what his motives are."

And then there's Jeff Goldblum's character, who, apart from acting uncannily like Jeff Goldblum in real life, performs a vital function for the telling of a story as relatively complex as Jurassic Park.

"There's no epiphany for Malcolm," says Spielberg. "He has a line in the movie where he says, 'I hate being right all the time.' He's kind of that useful character in a movie that stands around telling everybody that their best laid plans are going afoul, the 90s equivalent of the soothsayer of doom standing around the streets of New York with a sign saying, 'Doomsday is near.' He's the mathematical equivalent of that. Jeff was tremendous type-casting for this part, and he will not be a surprise to anybody 'cause he's perfect for it."

Although Spielberg and his two screenwriters decided no love story could work in their film ("It would have to be a mating between a triceratops and a stegosaurus"), Grant and Ellie are quietly moving towards long-term goals, and there is a hint of relationship there, chaste though it may be.

"Ellie loves to imagine what the dinosaurs ate, and Grant loves to imagine where they evolved," says Spielberg. "They have a relationship based on working together on palaeontology digs and they complete each other's sentences. Right in the middle, they get separated and Grant is really on his own. The romance is all pretext, all prologue. I'm going to make a love story someday, and then people will be able to say, 'Well, he can do a love story' – but this certainly won't be that one."

He did have a crack at the territory, of course, with his A Guy Named Joe remake, Always – though Holly Hunter and Richard Dreyfuss were doomed to be forever apart in their corporeal form, if forever together in their souls...

"Yes, Always was a frustrated love story," agrees Spielberg. "Once again two people coming together for a kiss, and then something happens and the kiss dematerialises into a kind of spiritual rebirth of this girl – a girl who's sort of been struck dead by her boyfriend's death..."

For the past few minutes, Michael Crichton (bound to be noticed at six-foot-nine) has been standing nearby watching the crew of Jurassic Park make ready. He's colluded in most of the revisings of his book, maintaining the easy temperament and the wry smile of a man who has two prospective book-into-movie hits coming out in the US this summer (Rising Sun, starring Sean Connery and Wesley Snipes, being the second). The 51-year-old Harvard graduate has already sold his next, soon-to-emerge novel of sexual harrassment to Hollywood for well over a million dollars.

He and Spielberg first met in 1970, shortly after Universal bought the rights to Crichton's bestselling The Andromeda Strain. Spielberg was the lot wunderkind, then directing Joan Crawford in an episode of Night Gallery, when studio execs dispatched Spielberg to give the big man a tour. Spielberg misled him about the movie business, Crichton recently confided to the Los Angeles Times, encouraging Crichton to have a crack at directing, most successfully with Westworld and The Andromeda Strain.

"He's so rational, so organised, so intelligent," he said, "it made it seem like something a reasonable person would do." Now, about to see the eighth of his novels turn into a movie, he's wiser – and considerably richer – and has left directing to the likes of Steven Spielberg. He trusted Spielberg to have the chops and the clout to get Jurassic Park done right, but he's not expecting Citizen Kane. Speaking recently to a luncheon of media types who asked what issues the movie would plumb, he half-jokingly promised only that it would "scare a lot of kids."

People always accuse me of merchandising my movies ad nauseam, but I don't spend much time on that. – Steven Spielberg

What it will also do, however, is bring into sharp relief the extraordinarily intertwined relationship between books, films, theme parks, merchandising, and marketing in the 1990s. There is even a scene in the movie in which the camera pans across a shelf filled with Jurassic Park lunch-boxes, t-shirts and fluffy toys, trinkets that could literally be plucked from the set and sent to Hamley's to sell on the back of Jurassic Park The Movie.

"I'm not sure what my merchandising is", insists Spielberg a touch testily. "People always accuse me of merchandising my movies ad nauseam, but, in fact, I don't spend much time on that. I have a company run by a colleague, and whatever the major distributor of the film is, they handle the merchandising, so I don't really know – aside from the fact I know our toys are Kenner this time, and I know we have a McDonald's tie-in."

That may sound slightly disingenuous, until you look at Spielberg's schedule. He sped from intense post-production chores on Jurassic Park straight into winter shooting in Krakow for Schindler's List, keeping in touch with California via a "live two-way, scrambled satellite transmission between Industrial Light And Magic (ILM) in San Francisco and here," continuing post-production with his head full of the Holocaust.

"The Jurassic editing was done before I started shooting Schindler's," he notes, "but we had to work on all the dinosaur effects. I went to Paris to dub the picture and correct the colour. It worked quite well – I was able to make my movie, even though 40 per cent of the post-production was done long distance."

To keep Universal happy, Spielberg had to offer the studio the guarantee that his long-time friend and collaborator, George Lucas, would oversee any post-production that Spielberg couldn't physically manage.

"Otherwise, the studio wouldn't have let me make Schindler's until Jurassic Park was in the theatres," he explains. "I was desperate to make it on the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto, of the Holocaust at its height. I wanted the film to come out in '93, because of everything that's happened with ethnic cleansing with the Serbs – and the Kurds, with Saddam Hussein. You know, 22 per cent of American kids don't believe the Holocaust happened."

Despite Spielberg's love for his adaptation of Thomas Keneally's book about the Holocaust hero, you can glimpse his fondness for Jurassic Park in his description of the score, composed by his twelve-time collaborator John Williams – the man behind Jaws' legendary dum-dum-dum-dum theme.

"It's what you might expect to hear if you had a lot of respect for the oldest living creature in history brought back to life," he says. "You would take your hat off and watch it walk past with a tear in your eye, and say to yourself, 'God did good work.'"

He's proud, too, of the look his computer experts gave the dinosaurs, aware that they mean a milestone in movie technology. Yet there's wistfulness in his tone when Spielberg talks about the newfound ability of computers to create the cinema version of virtual reality – and an acknowledgement that Jurassic Park will change motion pictures for ever.

"I don't think we can ring the death knell on production design this soon," he says. "But when the time comes where it will be more cost effective to create the sets in a computer as opposed to building the Roman Forum in practical scale, that's a day I will rue and mourn. And that day is coming – I'll move into the technology along with everybody else, because that technique will be the only way that filmmakers with big imaginations will be able to afford them."

Whether it is via this new technology or by making serious movies like Schindler's List, the day could indeed be coming when Steven Spielberg is relieved of the curse of being seen as a filmmaker constantly exorcising his troubled childhood ("Just a pervading unhappiness you could cut with a fork and spoon every night"), albeit with stunning box office success.

"He is constantly creating, because making movies is like playing," fellow icon Michael Jackson said in 1985. "He will always be young."

"The movies I make have to pass through me before they get to the screen," says Steven Spielberg simply. "I'm stuck with who I am..."

The dinosaurs really do look like living, breathing animals. So, how the hell did they do it? Traditionally, dinosaur movies have relied on stop-motion animation to bring creatures dead for 65 million years back to life, a process in which jointed, armatured models are moved a fraction at a time and photographed frame by frame, and which when the film's at normal speed gives the impression of movement. For Jurassic Park, however, Steven Spielberg was determined to film as many of his dinosaurs "live" as possible – in other words, filmed on set with the actors – using full-size robotic (or animatronic) creatures. With this in mind, he approached Stan Winston, a three-time Oscar winner who already produced the screen's biggest "live" creature to date – the 15-foot Alien Queen from Aliens – to create the dinosaur cast, including a 20-foot high T-rex, a pride of vicious velociraptors, a sickly triceratops (or, er, T-tops?), a venom-spitting dilophosaurus, and a tree-munching brachiosaurus.

While Spielberg hoped to shoot much of the dinosaur footage live, he did understand that certain shots – full-body views of T-rex stomping around, for example – would have to be obtained through other means. Back in the early 80s, George Lucas’ special effects company Industrial Light And Magic (ILM) had, for The Empire Strikes Back, come up with an alternative to stop-motion called go-motion in which puppet characters were moved via a series of rods attached to computer controlled motors. This meant that the movements could be stored in the computer's memory and be repeated at the touch of a button. With this in mind, Spielberg brought in Phil Tippett, an Oscar-winner for his work with ILM on Return Of The Jedi and considered by many to be the top model animator, to produce the 50-60 go-motion dinosaur shots which would supplement Winston's full-size creations

Spielberg had, however, also been in contact with ILM's head of visual effects, Dennis Muren, a seven-time Oscar winner who'd worked with Spielberg on E.T. and the Indiana Jones trilogy, in regard to a stampede sequence in Jurassic Park that features a herd of gallimimus dinosaurs, which he had no idea how to film. While Jurassic Park's script went through numerous revisions and Spielberg went off to make Hook, Muren and ILM took computer-generated effects to a new zenith with the astonishing morphing that transformed actor Robert Patrick into the shape-shifting metal fluid T-1000 killing machine in James Cameron's Terminator 2.

After T2, Muren turned to the herd problem, which he felt was something that could be solved by computer graphics. Members of Muren's team had even greater ideas and secretly put together a computer programme featuring a skeletal T-rex which sold Spielberg on using computer graphics. Taking things one step further, Muren's crew used the data from one of Winston's T-rex models – gained by scanning the model with a 3-D scanner which then copies the image into the computer – and introduced it over the existing computerised skeleton. The result was such a success that Spielberg scrapped the go-motion idea and employed ILM to provide all the dinosaur footage that wasn't to be shot live, including a revised climactic confrontation between the T-rex and a pair of ’raptors that would have to be completely computer engineered.

Winston's crew, meanwhile, continued with their full-scale creations, sculpting them in clay and covering their complex skeletons and mechanisms in foam latex. For the T-rex, an internal hydraulic system was employed to provide the creature with its full range of movements. Split into two sections, the T-rex's head, torso and tail were mounted on a customised flight simulator, dubbed the "dino simulator", rigged to a computer control system, in turn linked up to a miniature T-rex operated by a team of puppeteers, whose movements could then be recorded by the computer. This "dino simulator" was used for all "up-angles" on the T-rex, while for shots of the Rex's legs meeting the ground, a moving platform was constructed that featured the creature's underbelly, as well as hydraulic legs and tail. Winston's crew also constructed a separate T-rex head with extra detailing and more mechanics which was used for close-up work and featured a complete range of facial movements.

For the agile velociraptors, Winston employed both high- and low-tech approaches, ranging from a man-in-a-suit to full-size mechanical puppets with radio-controlled mechanisms for the eyes, and a tail operated by concealed rods.

From initially being employed to provide only the herd stampede, ILM found themselves charged with producing 52 computer generated shots, including full-body and close-ups of the T-rex, shots of the brachiosaur and a number of ’raptor shots which would have to be interspersed with Winston's creations, in addition to the new finale. Despite their dazzling work on T2, the task set – to produce organic computer generated dino skin as opposed to metallic sheens – was a daunting one. ILM not only had to make the dinosaurs move, they had to make them appear to be living, breathing creatures with rippling muscles and moving bone understructures.

Using Winston's models as the basis of their designs, Muren's team would create the dinosaurs in their computers, first building up the skeletal structures, then the muscles and the skin, giving the computer animators complete control, down to being able to make individual muscles bulge on cue. For realistic dinosaur movement, Muren teamed up with Tippett to create DID – the Dinosaur Input Device – which meant Tippett's team of animators could animate sequences using armatured model dinosaurs equipped with encoders at pivot points, and their movements could be recorded on the computer. The finished computer imagery was then added to background shots featuring the actors reacting to the imaginary dinosaurs – as with many movies, editing was done in the computer, then transferred to conventional 35mm film.

The result of Winston's, Muren's and Tippett's crews combined efforts adds up to the most stunning special effects ever created on film.

"When we first started on Jurassic I didn't expect the computer graphic dinosaurs to be as spectacular as they are," admits Muren now. "But these dinosaurs are absolutely unlike anything you've ever seen before..."

This article was first published in Empire Magazine Issue #50 (August 1993).