Back In The Swing Of Things: Harry Potter director David Yates takes on the challenge of bringing Tarzan back from the wilderness.

This feature first appeared in the July 2016 issue of Empire.

Five years ago, David Yates might justifiably have taken a very long holiday. The director had just said goodbye to Harry Potter with the series’ final instalment, The Deathly Hallows Part 2. After four films, half a decade, and north of $4 billion in box office, he’d certainly earned a break, but his thoughts were nevertheless already turning to his next project. Stacks of screenplays were coming his way – “Lots of sci-fi, lots of things blowing up”, he says. The director who’d just brought one of cinema’s most successful series to a spectacular conclusion had his pick. But one in particular called out to him. A surprising one.

“The Legend Of Tarzan felt the most enjoyable of everything I’d been reading,” Yates tells Empire. “I just liked the idea of a really old fashioned and joyful romantic action-adventure picture. Tarzan had gone out of fashion, and wasn’t necessarily ever done that well in its earlier incarnations, but they were delightful in their way. And I felt that, just as Batman had been through reinventions, Tarzan was ready for that too.”

It would hardly be his first. During the 20th Century the lost, ape-raised English lord was ubiquitous. His creator Edgar Rice Burroughs alone wrote more than 40 novels and short stories about the loin-clothed jungle adventurer between 1912 and 1947. Other authors (among them Fritz Leiber, Philip José Farmer and Andy Briggs) later wrote even more. There were comics, cartoons, stage plays and radio serials. And there were movies: at least 90 between the silent era and today. The most popular series, which began with Johnny Weissmuller in the title role in 1932 and ended with Mike Henry in 1968, ran to 28 films.

After that, the pace began to slow, but there were still live-action TV shows, school-holiday re-runs of the old films, and occasional cinematic adventures: the ill-fated erotic take with Bo Derek in 1981 (Tarzan, The Ape Man); Hugh Hudson’s handsome-but austere [Greystoke: The Legend Of Tarzan, Lord Of The Apes]((http://www.empireonline.com/movies/greystoke-legend-tarzan-lord-apes/review/) in 1984; and Disney’s animated 1999 version. The character’s popularity endured. “I was a Tarzan fan; that’s why I came to this,” says Samuel L. Jackson, who plays US envoy George Washington Williams in Yates’ movie. “Gordon Scott was my Tarzan on the big screen, but I watched Johnny Weissmuller on TV. We played Tarzan when I was a kid, and jumped from tree to tree and did shit.”

We haven’t, however, seen a live-action Tarzan on a cinema screen so far this millennium. Not counting the mo-capped German film with Kellan Lutz, or the swiftly cancelled WB TV series of the early 2000s starring a pre-Vikings Travis Fimmel, the last actor to swing on a vine with Jane was Casper Van Dien in 1998’s Tarzan And The Lost City… which had its budget slashed during production, limped to a paltry $2m at the box office, and has never even been available on DVD in the UK.

So it’s hardly surprising to learn it took producer Jerry Weintraub a decade to get The Legend Of Tarzan into production. Directors Guillermo Del Toro and Stephen Sommers came into and out of the picture in 2006 and 2008 respectively, before he finally locked things down with Yates, and an entirely new script, in 2012.

Even after that, there was a temporary shut-down in 2013 over budgetary concerns. “It’s been a real struggle to match the vision with the money,” says Yates, though he’d achieved that by the time the film finally went into production in February 2014. John Carter – another Burroughs property – didn’t help his cause, with Disney’s high-profile adaptation bombing in 2012. While, even in a dormant state, Tarzan retains wider cultural name-recognition than Carter, reviving him remains a risk in a world where the modern superhero blockbuster is all conquering.

“I actually do think of this as a superhero movie,” says David Barron (Yates’ producer on this and his Harry Potter films). “Tarzan’s senses are very finely tuned and he has this great physical prowess as a result of his upbringing. It’s not a superhero movie like we’re used to, though: we are treating it as a proper, grown-up Tarzan story based in reality.” Yates insists this is “a modern, eco-Tarzan. His world is amazing, and it deserves to be represented properly, in a way that’s really possible now, with that proper wallop of action and entertainment and scale.”

Don’t confuse “modern” for “present day”, however. Part of Tarzan’s charm, for Yates, lies in his historical setting: the wild animals, the tribesmen and the verdant Congolese vistas. At source, those elements are potentially problematic, stemming as they do from Burroughs’ ignorant fantasies: the ‘Scramble For Africa’ was far from over at the time Burroughs first began writing. By 21st-Century standards, Burroughs’ work is naively racist, so key to Tarzan’s reinvention was rooting him in an historically accurate past: “redefining him by an understanding of the world,” as Yates puts it.

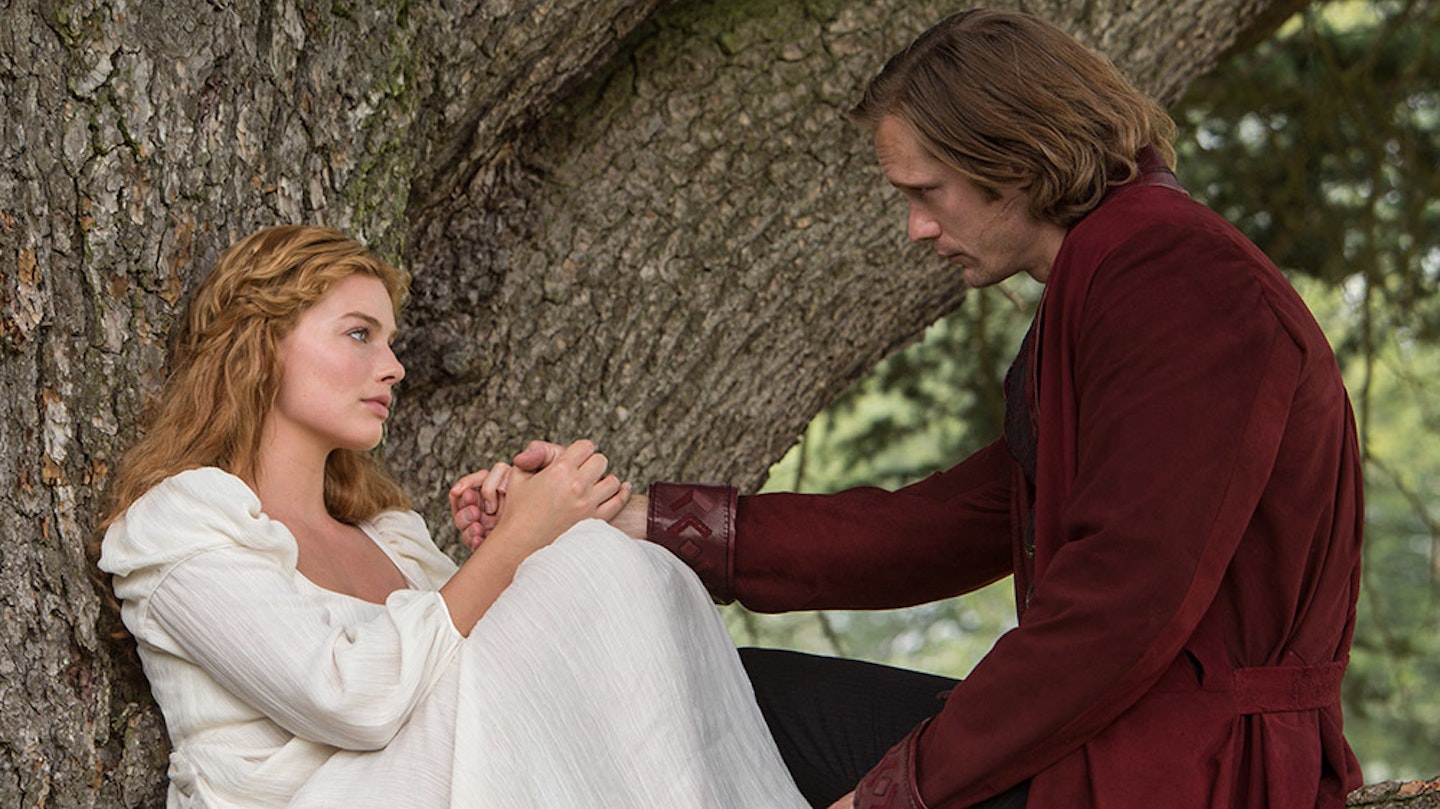

Avoiding the obvious route of the much-told origin story (although Yates says there are more early-Tarzan flashbacks than were planned, due to test audiences “longing for them”), screenwriters Adam Cozad and Craig Brewer introduce a Tarzan already living in England as John Clayton, Lord Greystoke. Plucking a thread from Burroughs which saw Tarzan, as early as second novel The Return Of Tarzan (1913), already undertaking diplomatic missions for European governments, The Legend Of Tarzan plunges him back into the Congo on a joint British-American operation to investigate the dubious activities of the Belgian King Leopold II.

A real historical villain, during the late 1800s Leopold ruthlessly exploited the Congo for its rubber crop, resulting in mass enslavement and genocide. Modern estimates put the number of Congolese deaths attributable to his regime in the millions. With this as a context, you can hardly accuse the film of romanticising colonialism. “Obviously it’s a big exciting action film,” Yates’ Tarzan Alexander Skarsgård explains, “but this is the reality that Tarzan comes back to in the Congo: an appalling situation that wasn’t there when he was growing up.”

Outside Africa, Leopold was presenting himself to the world as a philanthropist, and when bankruptcy threatened, he appealed internationally for financial support. So Tarzan joins Williams on a fact-finding mission that quickly goes wrong. Leopold himself doesn’t appear onscreen, but his dastardly interests are represented by the movie’s principal villain, Léon Rom (Christoph Waltz). Both Williams and Rom are historical characters: Rom is thought to be an inspiration for the brutal Mr. Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness; Washington a lawyer and Civil War veteran whose open letter to Leopold in 1890 hastened the end of his so-called Congo Free State.

“I didn’t know George Washington Williams’ story until I started talking to people about this job,” says Jackson, “but after that I read a lot. He was the first African American from the United States to go into the Congo and oppose the slave trade. He was an interesting guy.” He’s also a counter to the “white saviour” trope, by which white characters solve problems for people of colour: one more example of The Legend Of Tarzan’s attempt to be culturally and racially cognizant.

“We were very sensitive to the more dated aspects of the classic stories,” says Yates. “One of the appeals and challenges of the script was that it was rooted in this terrible, powerful, disturbing aspect of African history while still keeping all the iconic aspects of the Tarzan you know. If even one person in that multiplex audience goes away and reads a little bit about George Washington Williams, we’ve achieved something.”

Though African history was important to the production, Yates didn’t shoot in Africa itself. Playing the part of the Congo is his old Harry Potter stomping ground, Leavesden Studios (new Jane Margot Robbie, when Empire meets her on set, is excited to learn that we’re standing on Hagrid’s Hill). Only some plate shots, to “wrap Gabon around the sets”, Yates says, were filmed on location.

There’s something fitting about this. The films of the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s were similarly shot on studio back lots, with the more exotic animals slotted in via stock footage. But they were B-pictures through and through, lacking anything close to the budget Yates has to facilitate some extraordinary production design. “The old films were always a bit under-realised,” says Yates. “This time we’ve got the resources, even though we’re only in Watford!”

Empire can hear the M25 from the savannah village where we watch Skarsgård, Robbie and Jackson arrive to a spirited tribal welcome. We can also hear it from the mountain valley set, with its 50-foot waterfall and craggy cliffs. But it’s at least quiet within C-Stage, which houses the production’s magnificently realised Congolese jungle.

There’s a smell of wet peat and bark as we poke around here. Mud squelches underfoot, and water gathers at the roof creating a misty micro-climate. Massive canopies of hand-moulded leaves brush against us as we meander alongside a river with a fully adjustable water level. You can walk a long way through this jungle before encountering any technology — as long as you don’t look up to see the light boxes on the ceiling.

While the flora may be physically present, the fauna – including thousands of wildebeest which stampede through the colonial town of Boma at the film’s climax - are entirely digital. Which is less of a surprise than the fact that Yates and his team have avoided the performance-capture approach, even for the apes.

“I didn’t want to tie myself into human performances,” explains Visual Effects Supervisor Tim Burke. “We don’t need our animals to do things that are unnatural for them, as they did in Life Of Pi or Dawn Of The Planet Of The Apes. Our creatures are in their natural habitat.” Again, rather appropriately, the film is using something akin to those old stock-footage-animal-insertion techniques, albeit in a vastly more sophisticated manner. “We’ve been capturing a lot of reference at wildlife parks in Gabon and in this country,” Burke continues. “We’ve been photo-scanning real animals. It’s all been about creating a library of performance.”

Once Yates is done with his other 2016 movie – Harry Potter franchise extension Fantastic Beasts And Where To Find Them – he’s ready, he says, to return to his new/old hero… Assuming his epic, big-budget and tonally modernised approach lands with the 21st-Century audience. “We’re excited,” he says. “We’ve been thinking a lot about a second Tarzan and how it picks up from this one. It all depends on how it does in July, but we’ve got a pretty good outline and we’re ready to go with that straightaway.”

Superman was created in 1938; Batman in 1939; Captain America in 1941. 104 years after his own first appearance, it feels right that Tarzan, the Lord of the Jungle, is about to return alongside them. He’s been gone for far too long.