A glorious on-screen life that began with Hawks and Bogart and ended with Seth MacFarlane and Family Guy was, as Lauren Bacall put it, a “zig-zagging” affair. One of the last stalwarts of Hollywood’s golden age, she graduated from shy model to neophyte actress to movie star to a true icon of cinema in the space of five decades of fame and contrasting fortune. Right into her last years living on New York’s Upper West Side, she continued to burn brightly on stage, winning two Tony Awards, and turned in notable big screen performances too. From those early days on the Warner Bros. payroll to the 21st century, here’s our tribute to the late, great Betty Bacall.

Lauren Bacall’s cover-star beauty parlayed directly into an acting career when Howard Hawks’ wife Nancy spotted her adorning this 1943 cover of Harper’s Bazaar (the queues for this particular blood donor clinic aren’t recorded), chosen by legendary fashion editor and trend-spotter Diana Vreeland. She’d already tried her hand at acting, performing in a George S. Kaufman play Franklin Street as a shy 18 year-old, but it was Hawks who shaped and prepped her for stardom in a medium she'd master with what seemed like effortless skill. In truth, it was anything but. Bacall’s famous “Look” came in response to the crippling anxiety that washed over her when she stepped onto her first film set. “One way to hold my trembling head still was to keep it down, chin low, eyes up to Bogart,” she later remembered. “It worked.”

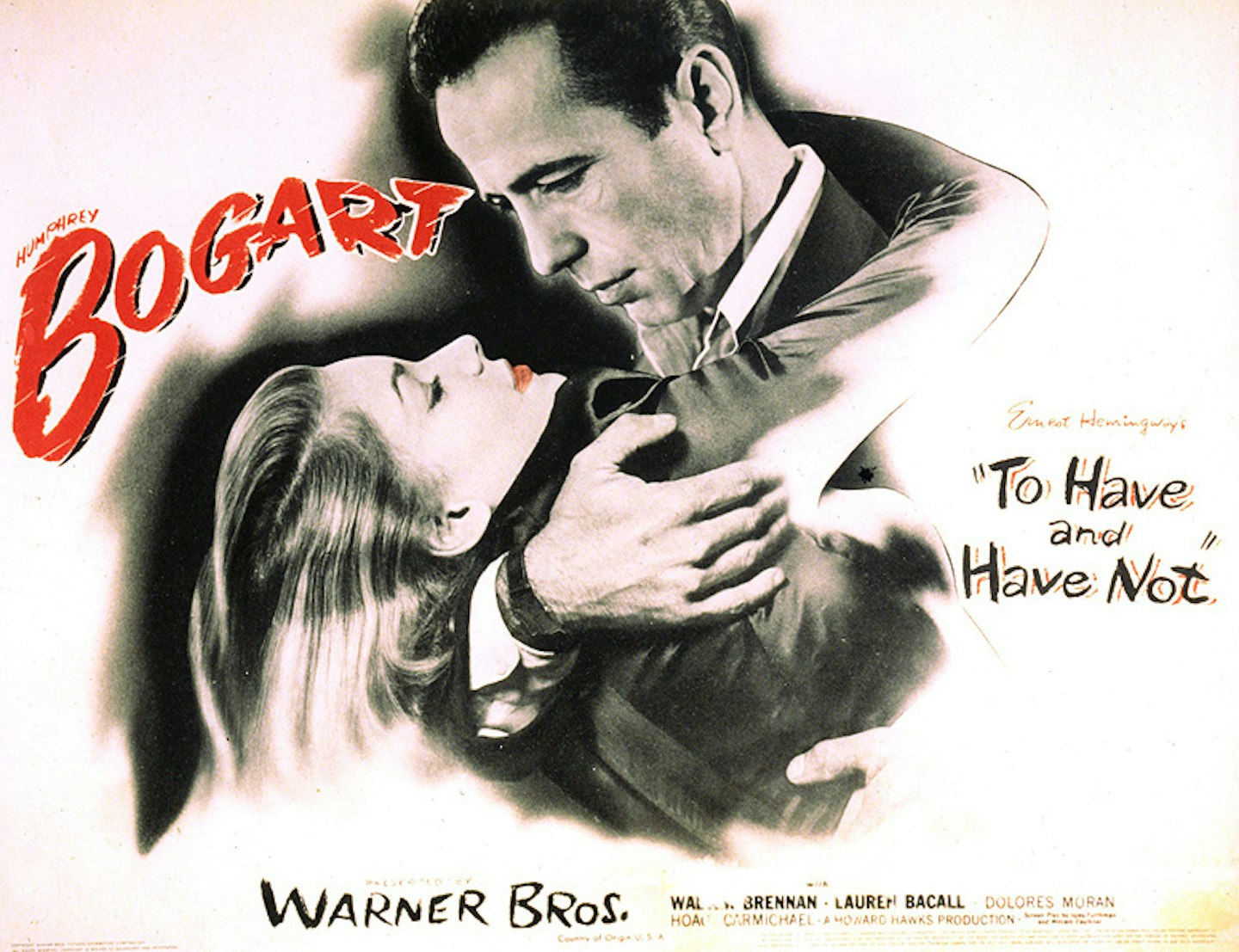

The one where she taught the world to whistle, this Hemingway adaptation launched Lauren Bacall into the stratosphere. Like Hitchcock and Hedren, Howard Hawks fixed on her with a view to making her a star. He succeeded, and then some. Encouraged to bury her nerves – and at 19 playing opposite mega-star Humphrey Bogart, there were plenty – she hid them beneath a smouldering mystique that threatened to burn through the celluloid. “He was the old gray fox”, recalled the actress of their off-kilter relationship, “and he always told me stories of how he dealt with Carole Lombard and Rita Hayworth, how he tried to get them to listen to him and they didn’t, so they never got the parts they should have gotten, and their careers took much longer to take off.” It was Hawks who leant on her to adopt ‘Lauren’ as her new first name.

Bacall’s relationship with Humphrey Bogart, the great love of her life, had inauspicious origins. Essentially, she didn't think much of him. Hawks had promised to cast her alongside either Cary Grant or Bogart in her first film role, and she'd had the svelte Englishman rather than the weathered New Yorker in mind. “I thought, ‘Cary Grant — terrific! Humphrey Bogart — yuck!’,” she recalled in Vanity Fair. But the pair had fallen in love on To Have And Have Not, married and by the time it came to Hawks’ great noir, they were generating more sparks than Guy Fawkes’ night at a welder’s house. “I like that,” she purrs when they kiss. “I’d like more.”

The last of Bacall’s four collaborations with Bogie (the other, Delmer Daves's man-on-the-lam thriller Dark Passage, is also well worth hunting out) was a John Huston thriller in which she played a war widow holed up in a Florida Keys as bad weather and even worse men come sweeping in. By this point in her career, audiences were well-versed in her simmering sexuality, but Bacall’s scenes with one of those baddies, Edward G. Robinson’s bug-eyed mobster Johnny Rocco, were the best showcase to date of her steely defiance. “A wildcat?”, he reacts to one of her snarls. “Smell blood, huh?”

“Stardom isn’t a profession, it’s an accident,” Bacall famously said. By that rationale, she was reaching Mr. Bean levels of mishap by the time she came to appear in 20th Century Fox’s CinemaScoped confection: a star who could command the screen. Still, the caprices of Hollywood life had already revealed themselves. Bacall, who’d secreted herself away to enjoy married life with Bogart and had been picky with her parts, ceded top billing here to the comet-like Marilyn Monroe. The pair joined Betty Grable in a kind of anti-feminist Avengers, digging for man-gold in stretchy Cinemascope. Here’s proof that no matter how beautiful a star is, they look even better in widescreen.

Meaningful glances and repressed emotions are the stock-in-trade of Douglas Sirk melodramas, and here again a single raised eyebrow can be the surrogate for volcanic passions. From Bacall, playing a lovestruck secretary smitted by Rock Hudson’s oilman Mitch Wayne, came a subtly affecting turn as a smart, grounded character anchoring the tumultuous broil of booze and hormones around her. Pedro Almodóvar claims to have seen the film “a thousand times”, and Roger Ebert, while acknowledging its mixed reception at the time of release, lauded it as “a perverse and wickedly funny melodrama in which you can find the seeds of Dallas and Dynasty.”

Sidney Lumet’s all-star thriller cast Lauren Bacall as part of a thickly-accented line-up of suspects aboard the titular train. Also loose on Agatha Christie’s caboose was fellow silver screen great Ingrid Bergman, as well as Sean Connery, John Gielgud, Vanessa Redgrave, Anthony Perkins... and, well, everyone really. Bacall’s loud-hailer of an American socalite, Mrs. Harriet Hubbard, came with a 24-carat wardrobe and a suspicious number of dead husbands. While Poirot sniffed around those skeletons in Madam Hubbard’s cupboard, audiences were treated to an old-fashioned display of Bacall imperiousness.

Staunch Democrat Lauren Bacall gelled surprisingly well with die-hard Republican John Wayne in an elegaic tale that had poignant echoes of the actress’s own life. Her character, widowed homesteader Bond Rogers, tends to Duke’s ailing gunslinger on screen as she’d nursed the dying Bogart off it 20 years earlier. Don Siegel’s oater makes a decent companion piece to another dying-of-the-light Western, Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller, with Bacall, like Julie Christie in Altman’s film, proving a jaded yet still steely support for its flawed hero.

As a style icon who made trousers and shirts look like the last word in sartorial nous and someone who was a true Hollywood icon for most of her life, Bacall was always going to be a shoo-in for Robert Altman’s portmanteau satire. She lined up in the fashion world’s Expendables with the suitably Expandable-y name of Slim Chrysler.

Bacall finally scored Oscar nomination in Barbra Streisand’s kinda romance. The Mirror Has Two Faces was no Babsterpiece – it could easily be subtitled The Cinema Has Two Exits – but she showed that her star appeal hadn’t waned an iota as Streisand’s bossy on-screen mum. She single-handedly saves all the hammy sex capering from capsizing altogether with a flurry of withering glares, sassy put-downs (“I should never have encouraged you to speak,” she informs Mimi Rogers tartly at one point) and wordly elegance.

Something in Lars von Trier’s Breaking The Waves caught Lauren Bacall’s eye and she signed up to lend her wattage in the small but pivotal role of a town matriarch in Dogville. The forthright American and the provocative Dane might have seemed like a combustible mix but the pair got along well. “I was beside myself with joy,” she remembered of her casting. “He works in a way that nobody I’ve ever worked with works. He holds his camera on his shoulder, and you might be in the picture and not know it, so you have to pay attention. It’s all very weird, all of that.” The actress never lost her willingness to take risks – also witness her role in Jonathan Glazer’s Birth.