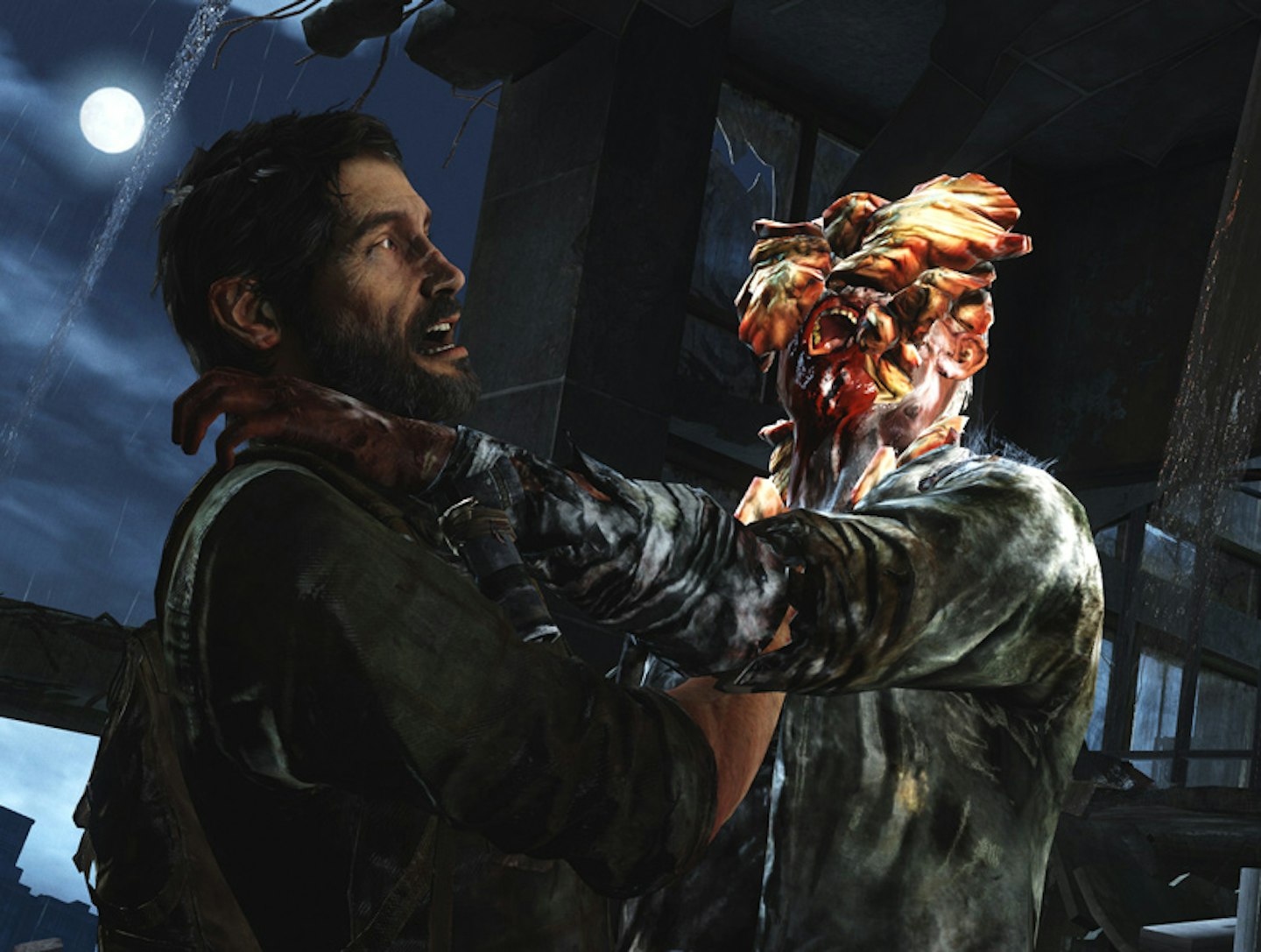

The Last Of Us is not a film, but if it were a film, it's a safe bet it would have appeared in more than a few of Team Empire's Top 10 lists. On the surface, it's an action-adventure survival horror game about zombies, fungal spores and the unlikely duo of a jaded 40-odd-year-old apocalypse survivor called Joel and a 14-year-old orphan called Ellie. Dig a little deeper and it's one of the most emotionally-affecting stories of the year, an intensely cinematic tale of fear, survival and friendship.

We spoke to developer Naughty Dog's Bruce Straley and Neil Druckmann about putting together the greatest film you've ever played, and how it all started with a screening of No Country For Old Men...

Bruce, you're the game director, and Neil, you're the creative director. What do those two roles encapsulate?

Bruce: Good question. The shortest answer is it takes both Neil and I to make the game. The job's too big to take on one of these 200-plus people team projects, and keep everything on track. So Neil handles story and characters, I handle gameplay and, moment-to-moment, what's happening in the game. But we have to really be on the same page and see eye-to-eye on everything. So we're kind of like Voltron, only there's just two components.

Neil: There's a lot of overlap in what we do.

So you two must be joined at the hip?

Bruce: (Laughs)**** We sometimes joke that we are in a relationship like a marriage, because to be able to communicate on the level that we have to communicate, to be so open and receptive, it is like a marriage, in a way. Of course our egos are going to get in the way. It's always an interesting adventure dealing with other humans on this kind of personal, creative, vulnerable level.

Neil: That's when this thing becomes really exciting: when people bring different ideas, or interpret the project in different ways... you get surprised by what it is. But the thing that worked for us is that we both had the same goal of, "How do we bring this relationship between Joel and Ellie to life?" Whether it's through story or gameplay or music, or anything that we have at our disposal, it was always under that goal, that focus.

Bruce: I think we're really lucky that Neil and I share a lot of the same interests, and have the same sort of tastes in media. Even before we worked on this, we worked together very closely on Uncharted 2, and we'd have dinners together and talk about movies and books, and gameplay in Uncharted 2, and so... I mean, that was kind of like the birth of this collaboration.

Speaking of movies, what films did you use as touchstones for creating The Last Of Us?

Bruce: It started, actually, with Children Of Men. And then we saw No Country For Old Men together – we went to a preview or showing somewhere, we kind of lucked out with some tickets at the last minute... I don't know, it was one of those things – and I hadn't heard about it, I hadn't seen a trailer, I hadn't read the Cormac McCarthy book.

We went into it blind, and I remember just walking out of that theatre... There was no air in my lungs at all, and I'm looking at Neil with the widest eyes ever, saying, "What the fuck did we just see? What was that?" And we had this very engaging conversation about it. And it continued, not just for that evening, but into the next day's lunch, and then another dinner. We kept talking about how we've never played a game that had that kind of tension and that kind of subtlety, and that kind of simplicity of music – there was pretty much no score. You were so present in every single moment of that film, and the development of Llewelyn Moss as a character who didn't have all this exposition. It was "show, don't tell" to the ultimate degree, and that was really intriguing for us as game developers. We'd say, "I've never played that type of game before, let's do that."

Neil: This produced really interesting challenges, trying to take this really minimalist approach. What's the least we need to do to convey these characters, these emotions, these tense moments? And throughout production we would deconstruct that film and its scenes, and try to figure out what the Coen Brothers were doing there.

And with that being, for many, the opposite of what other games are doing, how did you go about pitching this to your bosses?

Neil: I mean, we're very lucky in that our bosses just put a lot of trust in us. They put us in charge of this project and then just let us run with it. And I think very early on they understood what we were trying to do and the kind of tone we're after, and what it's going to take to pull it off. And it was a struggle, because we've never done something quite like this before. We're also kind of lucky that the studio's very focused on story. We've taken designers to Pixar story seminars - a story talk from Pixar that explains how they brainstorm, what's their story-telling process like. We've all gone to Robert McKee story seminars. So it's all kind of in our DNA, and we speak the same language. So it wasn't like a hard sell - it was more, "Let's take this approach."

And have you been in touch with Alfonso Cuaron or the Coen Brothers, by any chance?

Bruce: (Laughs) We wish! Do you have their number? That'd be awesome.

Imagine if the Coen Brothers were playing The Last Of Us right now.

Bruce: That would make me shit my pants.

Have you seen Gravity?

Bruce: Of course. I've seen it three times.

Neil: I've seen it twice.

So we can hope for some kind of game inspired by Gravity?

Bruce: The world that we, Neil and I, have been inside of for three and a half years making The Last Of Us... that movie nailed on the head, in every way, shape and form. It's so well done, so intense, so simple, all at the same time. It's a very inspirational movie, to say the least.

Neil: I remember feeling the same feeling I felt walking out of No Country when I walked out of Children Of Men. That story, for an action film, was brilliant in its simplicity. And I was upset that no game takes that approach. We don't need over-the-top aliens and all this stuff, it can be down at the very human level. And I felt very similarly walking out of Gravity. So we wanted to take that approach of a very character-driven, simple plot so we could just focus on characters.

Bruce: The thing that turned us on about this ‘genre' as we were exploring it was the tension that the world creates. It affords the characters to make really interesting, human-based decisions. And that's the thing, you want to see the human dilemma. What is it like to make these hard moral choices? And Gravity did that, and Children Of Men did that, and hopefully The Last Of Us did that, that's what we were trying to touch on.

Gravity mades you think of computer games in terms of the blurred lines between animation and film. Do you feel that you're filmmakers insofar as you're telling a story to engage with its viewers/players?

Neil: I mean, I'd say we're storytellers more than filmmakers. We constantly look at what is at our disposal. Sometimes it’s best to give the player a full spectrum of choice, sometimes it makes better sense to limit that choice, and sometimes, for a really emotional moment where we want to focus on the subtlety of expression on a face, the best thing we can do is remove choice. So we constantly challenge ourselves: "What is the best thing that the story requires right now?" We work that out, then that’s what we do.

Bruce: Yeah, it’s interesting just to think about this. Film really defines itself based on its form, right? It’s a filmic form, and it’s using film, right? But we use interactive media. For us, the word “video game” – as much as, you know, I’m not going to try and get all hoity-toity about this – but “video game,” that word was born in the age of Atari and Pong.

And the feelings that we’re trying to touch on with people and the experiences we’re trying to deliver are beyond that sense of "game", you know. As a matter of fact, we use that term sometimes in a negative connotation, when we were in development: “That feels too game-y.” If we’re a little too on-the-nose about something, or sometimes we’re being too overt about something and it feels too game-y. We'd make sure the way we move our cameras didn't feel too game-y.

So there is a filmic aspect – we definitely looked to, what with all of the years and years of experience of really intelligent people looking at that medium and working with the limitations of cameras and lenses and compositions. It’s interesting, actually – I said something to Neil yesterday about this – my brain is already versed in the language of film. So when we try to break those rules too much, as far as how we move the camera, how we manipulate the characters, and so on, it almost takes me out because it’s something so unexpected, right? My brain has to get retrained.

That was an interesting thing you could say about Gravity: Cuaron had the opportunity to do the craziest fucking things ever with the camera, and instead he limited himself. “What’s enough to make it intriguing, but not to the point that it gets ridiculous and takes people out of it?” And that’s an interesting and difficult choice, I think, when you have that kind of freedom, when it’s all CG-based backgrounds, or video games, or things like that.

Neil: And another thing we tried to do early on was to come up with certain constraints for our visual storytelling. For example, we don’t have any fades – everything is a hard cut. And even the way our camera behaves, we'd limit that by asking: “Could a human shoot this? Could we, in real life, shoot it this way?” So our cameras didn’t feel too much like CG film, and more like the game was shot by a real film camera.

Towards the end of the game, when you see the giraffes, that often makes players feel for a couple of seconds like they are in a film. Jurassic Park is mentioned a lot online.

Neil: Interesting. We think that's one of the most emotional parts of the game, and it's interesting that it's during a gameplay sequence – it's not a cinematic... you're in control, and you're coaxing Ellie to come with you, and the giraffes walk past – so that only would work in our medium.

There was Planet Earth footage used in the promo for The Last Of Us – was that the origin of the game, in effect, the cordyceps fungus that turns ants into 'zombie ants'?

Both: Yeah.

Neil: We were both watching Planet Earth around the same time. We came to work both saying, "Oh my God, did you see that bit where the...?" It's always so crazy – the nuttiest thing we could come up with, and there's already something crazier that exists in nature.

Bruce: Over the course of I don't know how many years – maybe 15 years – working at Naughty Dog, we would often find references online of inspirational environments you'd want to go to, and look at the incredible places that exist on earth, the rock formations and stuff like that, and we'd literally say, "We can't make that. That's too far-fetched. Nobody will believe that actually exists." Yet here's photo reference right here of it, on our computers.

And so, Planet Earth had that same feeling. When we were watching it, there were so many stories that made us come into work and say, "Dude, did you see that thing?" So on YouTube, there's all these parasitic creatures that live in a symbiotic relationship with other creatures that basically create zombie snails and zombie wasps and zombie spiders. There are all sorts of nutty things that are happening. Nature's pretty out of control.

Neil: And the thing that we were excited by that became the style guide later on was the contrast: the juxtaposition of this horror that's happening to this insect, and yet the beauty that it turns into once it's been infected.

You've made made no mention of any zombie films. When you were saying "No, that's too game-y" during production, were you thinking, "No, that's too zombie movie" too?

Neil: Hmm. We were definitely inspired by 28 Days Later, which we also felt was a very character-driven story, despite having zombie-esque characters. What we tried to avoid is what some games and some movies do, which is focus too much on how this thing developed – the whole plot and back story of the virus and infection and then doing over-the-top monsters. So we would try and avoid that and keep coming back to questions like, "What is this saying about our characters? How is this applying interesting pressures on our characters?" And that would be the focus. That would be the test we'd have to pass.

Bruce: Certainly we watched a lot of zombie flicks. I think The Crazies was one we touched on that we liked. Again, The Crazies, the remake – I haven't seen the original – but the remake, that was more character-focused. It got a little bit into the conspiratorial side of things, or some sort of larger scheme which, again, to add to what Neil was just saying, doesn't interest us.

And honestly, if you try and break it down to reality, to have that kind of privileged viewer, that wouldn't happen. You just happen to be the one ex-military guy or ex-cop who has allegiances with somebody working in the government who happened to be working on the covert plan to create... It's just so far-fetched, and it's been seen before.

What would actually happen is this: shit hits the fan, and then the internet goes down, and then all communications stop, TV's out, and the food runs out and nobody even cares any more. That big conspiracy is so irrelevant to how I'm going to get through the next day. I'm sure there's going to be, at the beginning of it, some sort of Children Of Men-ish religious outlash, and left-wing conspiracies. There's going to be all that sort of stuff at the beginning, but pretty soon that's going to die off, and survival's going to kick in.

Neil: That was what was great with Children Of Men – and even the book The Road – is that they don't explain why these things happen. It's not important.

Bruce: OK, can we go there for a second? The book The Road is better than the movie The Road. There, I said it. How about that?

Did you have a session where you just sat down for two days and watched films?

Bruce: No, it's ongoing – it's a life.

Neil: I'll go to Bruce and say, "Oh, you gotta see this," or he'll come back and go, "Oh, you gotta read this," and we'll keep swapping media that way.

No-one's ever suggested you move in together, right?

Neil: (Laugh) I don't think my wife would like that... That's a difficult plan.

On the casting of Troy Baker and Ashley Johnson – how did you find out about these actors? What made them perfect for what you were looking to do with the game?

Neil: Well, what's interesting is that we didn't have them in mind at all when we came up with these characters, and we had a pretty long casting session. And during the first casting session, we were trying to cast both Joel and Ellie, so we would alternate people coming in and auditioning for Ellie, and people coming in and auditioning for Joel. And Ashley Johnson was maybe second or third – I don't remember now because it's been three and a half years, but she came in and just nailed it. Like, Bruce and I were both there, and we looked at each other and were like, "That's our Ellie."

Bruce: That was an awesome moment. And again, it's one of those things where you're surprised by something. It's better than what you had in your mind, the way she brought that character to life. And for Joel we actually struggled for a long time. We finished that casting session and we didn't find our Joel. And then we had another casting session and we still didn't find our Joel, and we were going to hold a third one, so we brought Ashley in to be the reader. We'd had other actors sitting in for readers before. Kind of like, "Let's just see who'll have a good chemistry with her."

And then we were looking at a long list of people, and the casting person we were working with suggested Troy, and we looked at his IMDb and he'd done some Final Fantasy stuff, and looked at his headshot and he looked nothing like Joel – he was too young for it. So we were just like, "OK, let's just bring this guy in." And he stepped into the room and he and Ashley just had this pretty incredible chemistry. He started speaking, and he sounded like Joel. Like, he's this older, gruff guy. And it was pretty amazing how he brought him to life, and just seeing them together was like, "Yeah, these guys are our people."

Did the actors inspire any moments within the game?

Neil: There was quite a bit of that with Ashley being much tougher than we originally envisioned Ellie to be. There were also some gameplay constraints that inspired this change, but Ellie became much more capable due to Ashley's input. And she became a lot funnier, also because of Ashley's input, just because Ashley's really funny. And then for me, as far as writing dialogue, I'd listen to just Ashley speaking a lot, and just try to mimic that in the dialogue itself.

And for Troy – well, as you know, when we first came up with Joel he was much more like Llewelyn Moss – and he was meant to be much more quiet and reserved, someone who didn't express his feelings. But Troy played him differently. He played him as a character that let his emotions get the better of him. At some point we knew we'd either have to fight Troy's natural tendencies, or rewrite some of the scenes to play off of that. Like the scene in the ranch house where he has a fight with Ellie, a lot of that is because of Troy's input to that character. He brought that to life.

Looking back, is there anything you'd have done differently?

Neil: That's a hard one. Because the process of making a game is such an iterative process, it's kind of like looking at your life with no regrets. You can't go back and say, with 20-20 hindsight, "I wish I could do this and that." We had to go down certain paths which ended up being dead ends just to find out that they were dead ends.

Bruce: And some stuff got in there because we were out of time, so we had to come up with creative solutions. There was a point where you used to go into Jackson, which is Tommy and Maria's town, and you would see children there and how the town operates, and we couldn't afford to do that, so you saw it at a distance. And there were times when we'd think, "Oh, it would've been better to go inside," but actually with hindsight, looking at the whole game, it works better when you never go there. You imagine what this group that's trying to re-establish society is like, and it's better in your mind than actually seeing it.

What was the hardest bit of the story to iron out?

Neil: Probably the ending. For a long time we had this antagonist that chased you, because we felt that the story needed it. And the problem was that we had this cool ending, and we wanted to make it work so badly, but it needed this antagonist that chased you throughout the entire adventure to make it work. And it just felt very forced all the time, and no matter what solution we came up with, we made the story hinge there.

Who was the antagonist in that iteration?

Neil: Tess was the antagonist chasing Joel, and she ends up torturing him at the end of the game to find out where Ellie went, and Ellie shows up and shoots and kills Tess. And that was going to be the first person Ellie killed. But we could never make that work, so…

Bruce: Yeah, it was really hard to keep somebody motivated just by anger. What is the motivation to track, on a vengeance tour across an apocalyptic United States, to get, what is it, revenge? You just don’t buy into it, when the stakes are so high, where every single day we’re having the player play through experiences where they’re feeling like it’s tense and difficult just to survive. And then how is she, just suddenly for story’s sake, getting away with it? And yeah, the ending was pretty convoluted, so I think Neil pretty much hammered his head against the wall, trying to figure it out. I think he came up with a good, really nice, simplified version of that, and it worked out.

When you finished, what were your expectations of the game? Were you expecting any of the critical love that you’ve been getting?

Bruce: No… I thought it was going to be way more controversial and split people much more. I thought there’d be some positive people that really liked it and the other side of the coin: many, many more people that would be upset – upset in a lot of ways.

Neil: A lot of times we would say, “Man, we’re probably being too subtle with this stuff. There’s many people that aren’t going to appreciate how subtle this is, and aren’t going to pick up on these hints.” Because we’re asking a lot of our audience.

Bruce: There are no buildings that collapse…

Neil: Yeah, there’s no spectacle, so we thought commercially it wouldn’t be nearly as successful as Uncharted. And at the time – I’m sure Bruce felt this too – I felt like we’re making selfish decisions, because we were just making the game we want to play, and not worrying about how it’s going to sell or how it’s going to be received. Your ego is there, so you’re worried about that, but you’re not letting that drive your decisions. But then it was a pleasant surprise.

Bruce: Following up the Uncharted franchise and that success makes this different. Coming out of the doors of Naughty Dog and the prestige of that name being on the front of your title, the difficulty of creating a new IP, something that you feel is novel, unique, interesting and engaging – that’s hard. There is a lot of expectation there, there is a lot to get wrong, and we had all these lofty goals.

So yeah, that’s a lot pressure, and I think it worked because of the three years of us trying to figure out what the hell we’re making, what the voices of these characters are, what is the basic pacing that keeps the players engaged, what are the core mechanics and how do they feel? You know, it’s hard making video games, let alone good ones. Because of the trials and tribulations of three and a half years of development, you can’t help but to have some doubt inside of yourself.

Because we had to compromise so many times just to get this out of the door: we had to compromise on story, we had to compromise on background. There are so many things that make us say, “Man, I wish we could’ve had a little more time, we could perfect this.” But, like they always say, there’s no finishing something, it’s just released, or whatever that phrase is. Let it go. And so that’s the same thing with the games, and this is all dependent on technology too. So yeah, we had a tonne of doubts. I had a tonne of doubts.

Neil: What was also interesting was right when we finished, Sony hired some consulting group to do a mock review for the game.

Bruce: Oh yeah…

Neil: And then we got that mock review and it was kind of like an average score, and they were complaining that there’s not enough boss fights and variety, and we were like, “OK, that’s kind of what we expected would be some of the reactions.”

Bruce: Yeah, they were saying, “We want some kind weapons, or some kind of secret cool weapon from the government that could destroy the infected easier.”

Neil: “We want more different classes of infected to fight…”

Bruce: “We want to know about the government conspiracy…”

Neil: So that’s when we thought, going forward, “OK, that’s going to be how a lot of people react to this, it’s going to be this.” But we were, again, pleasantly surprised when people picked up on the stuff we were trying to achieve.

When was the last time you read that report?

Bruce: (Both laugh) It was a long time ago...

What about the sound design – especially the scene when you start up the generator. Were there fights about what the clickers should sound like?

Neil: With clickers, early on we watched some 20/20 TV journalism show, and they had this special about these kids that are blind, and they can see using clicking sounds. And they showed this kid skateboarding down the street, and he clicks. It sounds bad, because then you take that idea and turn it into something horrific, where it's originally this beautiful story about these kids, but we liked the idea of taking this benign sound and attributing it to something really scary – so when someone heard this very simple clicking sound, they'd be like, “Oh my God, there's something terrifying around the corner.”

And then Bruce and I would always try to balance it: “How do we make it creepy without being on-the-nose creepy?” Like, don't make it sound like a witch or a monster – it almost has to sound like it's in pain, it's got its own suffering. How do we bring out the humanity in this creature? And that's the thing we struggled with throughout production.

Some of the best moments in the game were Ellie’s casual conversations with Joel, when they weren't doing anything at all, or during a fight. How did you make it so you'd hear those bits of background and character spots?

Neil: We would start with the major story beats, which were the cinematics. Then Bruce would tell me the game is too dark... And then it's like, "OK, how do you find that glue, what are some interesting things for them to mention?" So then we'd be playing some levels together and say, “OK, ask Joel, 'What would he be thinking here?' Ask Ellie...” It's almost like you're taking on those roles.

And then just doing some improvisation, so when you bring the actors into the studio so they have those lines – and we wrote way more than we needed, so then we could pick and choose of what to sprinkle into the level – but they would improvise as well as far as they were watching a video of the level being played, and as those characters, they're reacting to the situation. So some of the stuff you're hearing is their improvisation.

Bruce: The interesting contrast between Joel and Ellie is that Joel saw the world pre-apocalypse, pre-shit hitting the fan, and Ellie was born after – she's 14, and it's 20 years since everything went bad. So that was the intriguing part to us: seeing those two on this journey in the survivalist condition every day, and then wondering what would they bring to the table as far as conversation went. What would interest Ellie being outside of the quarantine zone for the very first time? What would it be like to enter the woods? It may be mundane to us, like, “Oh trees, whatever,” but if you think about it, in the quarantine zone, there’s nothing there.

In the book, City Of Thieves , they talk about this Russian winter in World War II, in Leningrad, and cannibalism takes hold, and everybody's chopped down every tree inside of the city to use it for wood, for fuel... That is the stuff that would happen. So what happens when Ellie gets out of that? As much as the military's thinking, "Oh, we're trying to keep people alive and we're doing our best to sustain this environment, and we actually have a positive goal", what's really happening is dark and bleak in the quarantine zone. And then she gets outside and, sure, there are infected, but then there's all this beauty and nature is reclaiming the earth, and that contrast – Ellie needs to say something about that.

Neil: And day to day, you know, she's still a kid. So she's going to get excited by seeing a movie poster for a film she could never see. The idea of being an astronaut was always intriguing to us, because that's something she could never do – there's no chance ever she could do that.

It was fun to have Ellie react to things as you explore.

Neil: What was important to is exploring would result in those little discoveries about the relationships between the characters. So like the three of you are walking together – Ellie, Joel and Bill – and Tess had just died, and then if you go off and explore a house, we were like, "Oh, this could be a good opportunity for something. You've separated yourself from Bill, and Ellie could show up here and have a private conversation with you."

And it would feel like a pretty natural thing, because she's been wanting to say something to you. And you know, if you go pick up this note, we were like, "Oh, that would be a good opportunity for us to put Ellie right behind you, and then she would say, 'Hey, I'm sorry about Tess.'" And then it's a little sweet moment that we could create organically in the gameplay space.

Bruce: Our plan was to create content that the player's possibly not going to see. Usually it's so expensive to create anything in a video game – it takes so many people, and we tend to just go, "What's the critical path? What do the players need to see? Let's focus our budget and time and energy and resources on that." And this is really the first time that we said, "We want to have exploring and character development off the beaten path. What happens when you go to these nooks and crannies and corners?" I mean, you're right, that was actually a goal of ours was to try and reward people who wanted to go and explore.

Ending on a slightly flippant note - if there's a film, tell us you're casting Josh Brolin as Joel.

Bruce: (Laughs) That would be awesome. We like his work, for sure. Sometimes I have that conversation with Ashley Johnson – she actually said she thought Josh Brolin wasn't vulnerable enough. These are just theoretical discussions though...