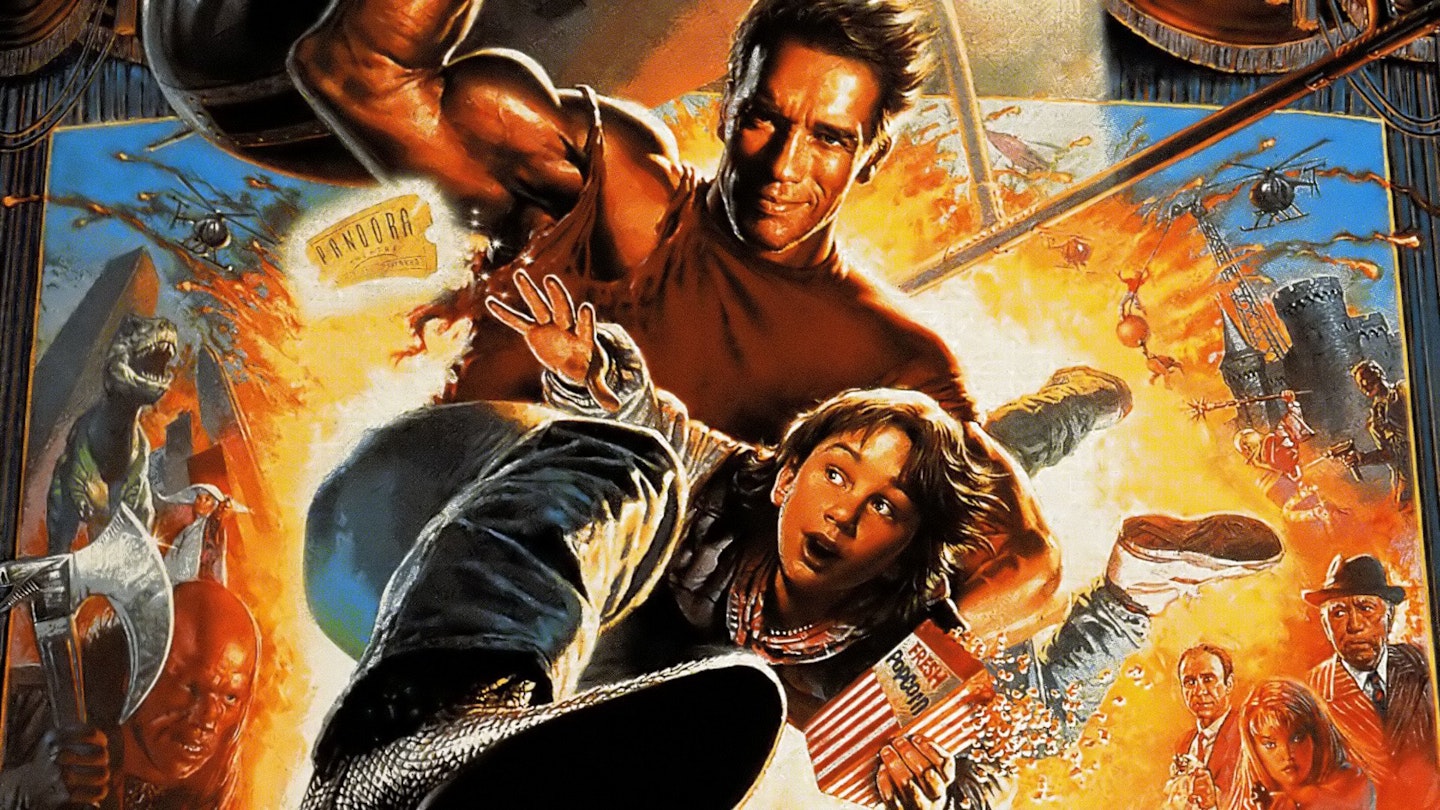

Die Hard’s director. Lethal Weapon’s writer. And The Terminator himself. Last Action Hero should have been bulletproof. Instead, it brought a studio to its knees, sent its cast and crew insane and proved, really quite conclusively, that some movies are not... too big to fail.

This article first appeared in issue 269 of Empire magazine. __Subscribe to Empire today{

The summer of 1993 was a bad time for Rainier Wolfcastle. One of The Simpsons’ most beloved minor characters, the Austrian action star is famed for co-owning Planet Springfield (along with “Chuck Norris, Johnny Carson’s third wife and the Russian Mafia”), and headlining the McBain franchise, which includes such entries as McBain IV: Fatal Discharge and McBain VI: You Have The Right To Remain Dead. But Wolfcastle’s lowest ebb is documented in classic episode The Boy Who Knew Too Much, as Bart Simpson spots him at a party.

*“Hey, McBain, I’m a big fan, but your last movie really sucked,” complains Bart.

“I know,” sighs the musclebound A-lister. “There were script issues from day one.”

“I’ll say,” chips in Chief Wiggum. “Magic ticket my ass, McBain!”

Rainier turns to his wife, shoulders slumped. “Maria, my mighty heart is breaking. I’ll be in the Humvee...”*

Wolfcastle is, of course, not real (and neither, sadly, is his movie I Shoot Your Face Again), but for the actual, non-yellow person he’s based on, there would have been nothing funny about this exchange whatsoever. With his own tale of a magic ticket that, yes, had script issues from day one, Arnold Schwarzenegger had just suffered his first devastating flop and a production process so agonising it’s become Hollywood legend. Friends became enemies. Vaults of cash went up in smoke. And Danny DeVito voiced a cartoon cat. The creation of Last Action Hero is the horror story that development executives whisper around campfires to this day. “The weird thing is that The Simpsons inspired it in the first place,” remembers Zak Penn, co-writer of the first draft. “We thought, ‘If this show can destroy genres even as it embraces them, why can’t we do it in live action?’ But somewhere along the way, the movie got lost. And nobody came out smelling like a rose.”

Last Action Hero was the worst time I’ve ever had in this business. * - John McTiernan***

Last Action Hero was the worst time I’ve ever had in this business. * - John McTiernan***

**

Penn and Adam Leff, two young graduates of Connecticut’s Wesleyan University, loved action movies. So in 1991 they decided to write an ambitious script, titled Extremely Violent, which would work both as a deconstruction of the genre and a kick-ass romp in its own right. “The basic idea was: wouldn’t it be cool if a kid got sucked into a silly action movie and used his knowledge of the genre to subvert all the clichés?” explains Penn. “We dubbed it Reverse Purple Rose after we realised it was the opposite of Woody Allen’s Purple Rose Of Cairo, where a character comes out of the screen into the real world.” For research, the pair visited their local videostore. “We rented every action movie we could think of and made a checklist. Does the second-most evil bad guy die before or after the most evil bad guy? Does the hero have a Vietnam buddy? It was fun, although watching Steven Seagal movies one after another can be soul-crushing.” Extremely Violent, which can be found online, lives up to its name. In the opening sequence, invincible cop Arno Slater takes on a horde of hitmen in LA’s Beverly Center, blowing them away with a laser-sighted hand-cannon while merrily dispensing one-liners such as, “Shopping can be hell.” The twist is, all this is revealed to be a trailer for a movie within the movie. Later, after the teenage hero has been yanked into the actual film, he uses his knowledge of the story’s beats to help Arno through the mayhem.

Penn and Adam Leff, two young graduates of Connecticut’s Wesleyan University, loved action movies. So in 1991 they decided to write an ambitious script, titled Extremely Violent, which would work both as a deconstruction of the genre and a kick-ass romp in its own right. “The basic idea was: wouldn’t it be cool if a kid got sucked into a silly action movie and used his knowledge of the genre to subvert all the clichés?” explains Penn. “We dubbed it Reverse Purple Rose after we realised it was the opposite of Woody Allen’s Purple Rose Of Cairo, where a character comes out of the screen into the real world.” For research, the pair visited their local videostore. “We rented every action movie we could think of and made a checklist. Does the second-most evil bad guy die before or after the most evil bad guy? Does the hero have a Vietnam buddy? It was fun, although watching Steven Seagal movies one after another can be soul-crushing.” Extremely Violent, which can be found online, lives up to its name. In the opening sequence, invincible cop Arno Slater takes on a horde of hitmen in LA’s Beverly Center, blowing them away with a laser-sighted hand-cannon while merrily dispensing one-liners such as, “Shopping can be hell.” The twist is, all this is revealed to be a trailer for a movie within the movie. Later, after the teenage hero has been yanked into the actual film, he uses his knowledge of the story’s beats to help Arno through the mayhem.

The script found a champion in Chris Moore, now a producer of such films as The Adjustment Bureau and the American Pie series, but back in 1991 an up-and-coming agent. “I saw it as a modern-day Wizard Of Oz,” Moore recalls. “The kid has a problem with his family. His father has left and he’s not getting on with his mom. And instead of getting whisked away to Oz, he does what most kids today would want to do, which is to escape into a movie.” He wasn’t the only fan. Penn and Leff watched agog as a bidding war unfolded, with Sony-operated studio Columbia Pictures ultimately prevailing by plonking down $350,000. More miraculous still, it attracted the attention of the star who had inspired Arno Slater in the first place: Arnold Schwarzenegger. “We never thought we’d actually *get *Arnold,” says Penn. “We were just two guys sitting in my apartment, thinking maybe someone would read it and get the reference. When we heard he wanted to do it, Adam and I looked at each other like, ‘This is insane.’”

It seemed their dream was coming true. But it was about to curdle into a nightmare. Hot off the success of Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Schwarzenegger was in no hurry to make a commitment. As well as Extremely Violent, he was considering a family comedy called Sweet Tooth, in which he would play the tooth fairy. Columbia top brass, desperate to bag the world’s biggest star, met with Schwarzenegger at his Santa Monica restaurant, Schatzi, where he puffed on a Romeo y Julieta Cuban cigar, sipped schnapps and explained that while he loved the concept — “Having a kid come into a movie awakens certain fantasies I had as a kid in Austria, like sitting on a horse with John Wayne” — the script wasn’t “executed professionally”. He also had concerns about Extremely Violent’s extreme violence.

*Arnold Schwarzenegger as Jack Slater *

To their dismay, Penn and Leff were swiftly dismissed from the project. Then, at Schwarzenegger’s suggestion, Columbia called in Hollywood’s hottest scribe. Shane Black’s first script, Lethal Weapon, had launched a lucrative franchise; his latest, The Last Boy Scout, had netted him an incredible $1.75 million. He also had history with Schwarzenegger, having played a commando alongside him in Predator. “The irony is that we’d gone to the MPAA library and read all of Shane’s scripts,” says Penn. “We were big fans of his — he was the Elmore Leonard of action movies. So it was this surreal moment of, ‘We’re parodying this guy, and now he’s been hired to rewrite us.’ It was just a strange, strange occurrence.”

*It was a mess. What they'd made was a jarring, random collection of scenes.

*It was a mess. What they'd made was a jarring, random collection of scenes.

-

- Shane Black***

**

To Black, who took a break from Iron Man 3 pre-production to talk to Empire for this article, it looked like easy work. “Me and my partner, David Arnott, were to take this very small script, where not a lot happens, and beef it up into a summer movie, with a lot of set-ups and pay-offs and reversals. Zak seemed to think that we ruined his script, but I was actually quite fond of what we came up with. We had a silly gag where Slater reaches up, grabs a scratch on the film and stabs a villain with it. I know Columbia told us at the time that they were very happy with it. But then, abruptly, things changed.” Black attributes the sudden chill to the hiring of John McTiernan, the man behind action classics Die Hard and Predator, as director. “McTiernan had made a lot of hits, so the studio said, ‘Let him do what he wants.’ And we watched as John rewrote the whole thing. I have a lot of fondness for John. He’s an interesting guy with a lot to say. He just wasn’t keen on the things we’d written.” Watching from the sidelines, the original writers became more and more anxious. “We always thought it would be someone like Robert Zemeckis or John Landis directing,” says Penn. “Someone with a history of pulling genres apart. I like Shane and I like John McTiernan — I wouldn’t have watched all their movies so many times if I didn’t. But I do think it’s easier for someone from the outside to mock the conventions of action movies than it is for the people who created them in the first place.”

To Black, who took a break from Iron Man 3 pre-production to talk to Empire for this article, it looked like easy work. “Me and my partner, David Arnott, were to take this very small script, where not a lot happens, and beef it up into a summer movie, with a lot of set-ups and pay-offs and reversals. Zak seemed to think that we ruined his script, but I was actually quite fond of what we came up with. We had a silly gag where Slater reaches up, grabs a scratch on the film and stabs a villain with it. I know Columbia told us at the time that they were very happy with it. But then, abruptly, things changed.” Black attributes the sudden chill to the hiring of John McTiernan, the man behind action classics Die Hard and Predator, as director. “McTiernan had made a lot of hits, so the studio said, ‘Let him do what he wants.’ And we watched as John rewrote the whole thing. I have a lot of fondness for John. He’s an interesting guy with a lot to say. He just wasn’t keen on the things we’d written.” Watching from the sidelines, the original writers became more and more anxious. “We always thought it would be someone like Robert Zemeckis or John Landis directing,” says Penn. “Someone with a history of pulling genres apart. I like Shane and I like John McTiernan — I wouldn’t have watched all their movies so many times if I didn’t. But I do think it’s easier for someone from the outside to mock the conventions of action movies than it is for the people who created them in the first place.”

Stress levels were rising fast on the project now called Last Action Hero, with Penn alleging that Black hung up on him during a phone call and Schwarzenegger still unhappy with the story. Before long, Black and Arnott were themselves fired and the increasingly choppy script sent to legendary writer William Goldman, who was paid an eye-watering $1 million for four weeks’ work. “Back in those days, that kind of thing was an insurance policy for keeping your job at an executive level,” says Black. “A script would be questionable and the trembling executive would give it to a famous writer with a million bucks, so he could say, ‘Yeah, it’s fortified now. We’ve given it vitamins. Wait, wait, wait... It needs the woman’s touch. Give it to Carrie Fisher!’ It just made people breathe easier, throwing money at this enormous behemoth. Even if the movie sucked, now they could say, ‘It’s not our fault.’”

As well as Fisher and Goldman, several other script doctors, including The Hunt For Red October’s Larry Ferguson, made nips and tucks. The projectionist of Danny’s favourite cinema went from demonic villain to kindly old man; a scene in which dozens of iconic movie villains invade the real world was added, then deleted; even Slater’s forename changed from Arno to Jack. Also new was a climactic premiere set-piece, where Slater — having escaped from his movie Jack Slater IV — would meet the real Schwarzenegger, the star sending himself up as a nitwit who won’t stop plugging Planet Hollywood. But the more money Columbia threw at the script, the more problematic it became. Late one night, a desperate McTiernan called Black, asking him to take a look at the action sequences. “I declined,” says Black. “We’d been fired and now they wanted us to fix up the explosions and helicopter scenes? I considered it an insult to my professional pride.”

Despite all this backstage brouhaha, in August 1992, Last Action Hero finally got its star and its green light. Any fears Columbia may have felt were swept under the rug — after all, with a $15 million fee for Schwarzenegger and a budget set for $60 million, it was fast becoming the most expensive film in Hollywood history. Studio chairman Mark Canton declared to the LA Times that, “Next summer is the season that will make me or break me. This is the big one. This is the best thing I’ve ever done.” Plans were rushed into action for Last Action Hero video-games, a line of Mattel toys, a $20 million Burger King campaign and a hard-rock soundtrack. And, in what would prove to be a fatal move, the event picture’s release date was announced. Whatever went down, it would open on June 18, 1993.

Austin O’Brien, who was cast as Danny after meeting Arnold Schwarzenegger several times, remembers the frantic pace once the shoot got underway at the end of 1992, and the star’s micro-management of the tiniest details. “During the first week on set we kept screen-testing cars — Arnold and I would drive around in different vehicles, trying to find an iconic car for Slater. That was such a strange process. I also remember Slater’s boots being a really big deal.” Schwarzenegger even opened his contacts book, recruiting friends and ex-colleagues. “I was doing ADR for an indie film when I got a call from Arnold,” says Robert Patrick, who’d battled him in Terminator 2. “He went, ‘Robert, I want you to do the T-1000 cameo you did in Wayne’s World for my movie.’ I think we even talked money, for Christ’s sake. It was just, ‘You have to do it for me! You *have *to do it for me!’”

“The whole thing would have profited from a little more digestion,” reflects John McTiernan. “The movie, from the moment the studio said they wanted to do it until it was in the theatres, was nine-and-a-half months. Which was a month too short. In hindsight, we were arrogant, too.”

McTiernan is a survivor. The director has been through a lot in the past two decades, from an acrimonious divorce to an ongoing federal case linked to the Anthony Pellicano wiretapping investigation, not to mention the Rollerball remake. So when he describes the final stretch of Last Action Hero as “the worst time I’ve ever had in this business”, you begin to understand the scale of the horror. To begin with, things went smoothly enough. Early on in the shoot, two reporters from Premiere were summoned to the Hyatt Regency Long Beach Hotel, where the La Brea tar pits had been recreated at gargantuan expense, complete with giant model dinosaurs. Arnold Schwarzenegger sat shirtless in front of his trailer, eating swordfish and joking about the ‘edible’ fake tar: “It tastes like mud with fungus in it!” Such was the on-set bonhomie, Premiere were told, that the star had played a prank on McTiernan, hiring a stripper for his birthday.

For O’Brien, who was getting to meet Michael Jackson and have Silly String battles with Arnie, it was non-stop fun. “Every day there was something amazing happening: a car flying over a truck or a huge gunfight,” he recalls. “And we had a big enough budget that if we blew something up and it didn’t look great, we’d do it again!”

Arnold discusses a scene with director John McTiernan (left)

Behind closed doors, however, tempers were fraying. During a set visit, Black and Arnott were told by a studio exec to pop into Schwarzenegger’s trailer. McTiernan saw it happen and later vented on them, furious, convinced they were conspiring behind his back. “I tried to explain,” says Black, “but after that John was just not the same towards us.” Penn was also back on the scene, having been offered a bit part in the film as a police officer. But even this reconciliatory gesture caused more bad blood. “After a couple of weeks, another actor turned to me and said, ‘Zak, I hate to tell you this, but if you look at where the camera is, you’re never in frame. McTiernan has basically blocked you out of the movie.’ You might be able to see my shadow if you look closely. I did laugh about it later, but it was so silly — why didn’t they just tell me to go home?”

*The harness was too tight. I couldn’t breathe. I passed out. It was scary.

*The harness was too tight. I couldn’t breathe. I passed out. It was scary.

-

- Austin O'Brien***

**

More seriously, the movie itself was in trouble, with McTiernan struggling to find the right tone. “The head of the studio couldn’t decide whether this was an action movie or a kids’ movie,” the director says now. “I was getting pushed in a lot of directions. When I was sent the script, the thing I liked was that it was wildly irreverent. But that was all getting watered down. And we were just trying to get the damn thing finished.” By the final few weeks, he and others were working 18-hour days.

More seriously, the movie itself was in trouble, with McTiernan struggling to find the right tone. “The head of the studio couldn’t decide whether this was an action movie or a kids’ movie,” the director says now. “I was getting pushed in a lot of directions. When I was sent the script, the thing I liked was that it was wildly irreverent. But that was all getting watered down. And we were just trying to get the damn thing finished.” By the final few weeks, he and others were working 18-hour days.

“I do remember that the deeper in we got, John looked more tired, more haggard,” says O’Brien. “He was great with me — when we got something right he’d turn into a little kid and start jumping around — but there was one day when I got a sense of how under the gun he was. We’d built a New York skyline inside the studio and I was hanging from a gargoyle, wearing a harness. It was so tight that I literally couldn’t breathe, but I was too nervous to say anything and I passed out for a few seconds. People were cutting my clothes off and it got kind of scary. But I do remember McTiernan coming up afterwards and saying, ‘In situations like these, I don’t care what’s happening, you tell me and we’ll fix it. Don’t be afraid. You haven’t done anything wrong, but we cannot afford to stop shooting.’”

If the filming schedule had been punishing, fresh hell awaited in the edit suite. A meta action-comedy like Last Action Hero requires precision cutting in order to make the jokes land and the stunts fly. According to McTiernan, he barely had time to unspool the reels. “It was something like three weeks from the end of shooting to when it was in the theatres,” he laments. “Do you know the old joke? The editing department says to Cecil B. DeMille, ‘The editors are dropping like flies.’ And DeMille says, ‘Hire more flies!’ We were living that. There are enormous sequences in the film that are literally how it came out of my camera. We cut the heads and tails off, and that’s the sequence; it wasn’t edited at all.”

Black finally patched things up with McTiernan and offered to take a look at the film. But he found it nearly impossible to identify a positive. “It was a mess. There was a movie in there, struggling to emerge, which would have pleased me. But what they’d made was a jarring, random collection of scenes. The casting of the little boy was one of the absolute misfires of Western culture. Also, they rewrote every line of ours, and I don’t like the dialogue they wrote.” Fragments of ideas sit uneasily together on the screen. A fantasy scene where Schwarzenegger’s Slater becomes Hamlet and knocks an enemy out with Yorick’s skull goes all the way back to Penn and Leff. The Mr. Benedict villain, played by Charles Dance with a range of lurid glass eyes, is a Goldman creation. And the scene where the heroic duo have to dispose of the expired, dynamite-stuffed body of a fat gangster called Leo The Fart is the handiwork of Black and Arnott, who borrowed the idea from Richard S. Prather’s murder mystery novel, The Meandering Corpse. “We thought it was a pretty swinging caper, where they gotta go hijack this bodybag. But John didn’t shoot the scenes that explained why the dynamite was there,” Black notes.

At some point, the simple central idea — that Slater abides in a ridiculous, Lethal Weapon-esque world filled with action-movie clichés — had become disastrously fuzzy. For instance, while the police-station sequence has funny gags about angry police chiefs and mismatched partners, it’s cluttered by baffling cameos: a Terminator, Sharon Stone as Basic Instinct’s Catherine Tramell, a cartoon cat called Whiskers and, strangest of all, a group of what appear to be space robots. “There were suddenly all these little in-jokes that worked against the story,” says Penn. “It turned into, ‘Let’s go to a videostore and do a joke about Stallone taking your parts. I don’t know about you, but I’ve never seen a Seagal movie where they go to a videostore.” Chris Moore agrees: “It had shot way off to the left of what was originally intended. If there’d been more time, there’s a chance someone might have stood up and said, ‘What the fuck are you doing with an animated cat?’ Something which, from the outside looking in, looks like a decision of somebody using drugs.”

Charles Dance as the movie's villain, Mr. Benedict.

Time was the one thing they didn’t have. After a disastrous test screening, where one audience member commented that the movie “lay there like a big fried egg”, a decision was made to reshoot the ending. Panic set in. But with so much money on the line, Columbia was desperate to maintain a confident face. In fact, it over-compensated, with the most ill-advised publicity blitzkrieg in movie history. Not content with spending a rumoured $750,000 on the trailer, the studio paid a further $500,000 to have the film’s name emblazoned on a NASA rocket, trumpeting that, “It’s the first time in the history of advertising that a space vehicle has been used.” Unfortunately, a glitch meant the launch was delayed until months after the movie’s release. The promo curse continued when a 75-foot balloon of Schwarzenegger holding sticks of dynamite was erected in Times Square. Given the recent truck bombing of the North Tower of the World Trade Center on February 26, 1993, it wasn’t the most tasteful gesture. The balloon was swiftly and sheepishly deflated.

It all seemed like karmic payback for the incessant braggadocio, with Schwarzenegger declaring at Cannes that, “I’ve turned out another great movie, and the critics have already said it’s a great summer hit,” and PR wizard Sid Ganis promising, “We’re heading for big numbers.” To McTiernan, up to his eyeballs in celluloid, it was just more grief. “I didn’t have time to get intimately involved in all the press disasters, but the advertising campaign was terrible. It did seem that if they hadn’t overhyped the movie, it would have been a lot easier to sell it. Because it’s actually sweet and kind of small in its heart. It isn’t Cleopatra. It’s the anti-Cleopatra. And if they had come on a little more quietly, it probably would have worked out better for them.”

%20

**

The budget was rocketing and time was running out. Yet an even bigger problem loomed. A problem 65 million years in the making. Steven Spielberg’s last film, Hook, had been a rare dud. It might have been this fact, or just good old-fashioned hubris, that led Canton to underestimate the director’s new project, Jurassic Park. When Universal announced that its dinosaurs-on-the-rampage blockbuster would open just a week before Last Action Hero, the Columbia boss refused to push back his own movie, despite the pleas coming from his own camp. “It was insane,” laughs Penn. “I rang him up and said, ‘I want to see Jurassic Park more than Last Action Hero, and Last Action Hero was my idea!’”

The budget was rocketing and time was running out. Yet an even bigger problem loomed. A problem 65 million years in the making. Steven Spielberg’s last film, Hook, had been a rare dud. It might have been this fact, or just good old-fashioned hubris, that led Canton to underestimate the director’s new project, Jurassic Park. When Universal announced that its dinosaurs-on-the-rampage blockbuster would open just a week before Last Action Hero, the Columbia boss refused to push back his own movie, despite the pleas coming from his own camp. “It was insane,” laughs Penn. “I rang him up and said, ‘I want to see Jurassic Park more than Last Action Hero, and Last Action Hero was my idea!’”

“Sheer stupidity” is how McTiernan describes the decision. “I saw Jurassic Park that summer: it’s a fabulous movie. But the studio tried to set us against each other, which was an idiotic thing to do. Because we weren’t the greatest action movie of all time. We were never supposed to be.” The rivalry became the season’s big story. Time ran a piece with the headline “The Dinosaur And The Dog”; some papers even reported on the contrast between Jurassic Park’s toys, which were selling like they were going extinct, and Last Action Hero’s, which were sticking to shelves, perhaps due to Schwarzenegger’s insistence that his action figure not be armed.

When Jurassic Park opened to a phenomenal $47 million — “Lizards eat Arnie’s lunch!” yelled Variety — the already gloomy Columbia lot became, in the words of one employee, “like the Nixon White House in the last days of Watergate”. And when Last Action Hero’s premiere rolled around, it was a predictably dispiriting affair. Like Jurassic Park’s John Hammond, Columbia spared no expense, spending a fortune on recreating Hamlet’s Elsinore Castle and dangling a Leo The Fart mannequin from a crane, but it was noticeably sparse on guest stars, despite each arrival being heralded over loudspeaker.

At the lavish afterparty, an elephant lumbered about the room (metaphorically, although you wouldn’t have been surprised to see a real one there). “Everyone ate the food and drank the drink and nobody said anything to each other about what they’d sat through,” says Black. “It was like, ‘Don’t talk about the movie, but these are some really good fucking canapés.’” Meanwhile, Penn sat miserably in the corner, at the event that once promised to be the high-point of his career. “It was not a pleasant experience. People kept saying, ‘Did you do all those fart jokes?’ ‘No, no, that wasn’t me.’ ‘Why did you have a kid thrown off a roof in the opening sequence? It made my kid cry.’ ‘I didn’t write that!’”

In the end, the film made $15.3 million during its opening weekend and $137 million worldwide, higher than the tally of that other ’90s misfire, Hudson Hawk, but still a huge disappointment. For Schwarzenegger, it was painful proof of his vincibility — though he’d temporarily bounce back with the business-as-usual True Lies, his action-muscleman heyday was over. “To be rejected so soundly — it sort of broke his heart,” says McTiernan. The director himself went into a deep funk, suffering from a uniquely Hollywood strain of PTSD. “That was a crazy time and you get to take a bite at the world as you find it. I’m happy I made it, but we pushed ourselves too far.” At least his friendships survived the experience — just. “After the movie came out, Arnold, John and I went for a beer,” remembers Black. “John couldn’t get his head around why it had gone so badly, because he knew there were troubles with the film but he was still proud of it. But by the end of the conversation we were getting really excited about the concept of the new Die Hard he was going to do. It was good to see him smile again.”

Nearly two decades on, emotions have cooled. Even Penn and Black, who recently crossed paths at the Captain America premiere, no longer want to kill each other in inventive ways. And despite all its flaws, Last Action Hero looks less like a disaster and more like an interesting, very expensive oddity. At least, unlike Hollywood’s current torrent of colourless sequels and mindless rehashes, it has ambition to burn. It blazed the trail for more successful genre parodies, like Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz and Black’s own Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. And Moore even harbours an ambition to one day remake it: “I’m sure you’ll put that in your article, I’ll get fucked out of it and some Sony producer will be shooting it next week.” All involved agree that the movie marked the end of an era of rampant Tinseltown excess. “In a way, it was the last of the smug big movies,” says Black. “Maybe Michael Bay’s are still this way, but there’s a smugness to Last Action Hero — a celebration of spending money in itself.”

Moore goes further. “It was a historical moment, where so many people saw this craziness unfold that it created an embarrassment and a ripple effect in the business. Somebody needed to step in and say, ‘Look, we’ve got some of the most talented people on Earth and a shit-load of resources — what is the actual movie we’re making?’ Instead, everybody avoided the hard conversations, so the movie attacked and ate itself. It’s the ultimate cautionary tale.”