Fifty years since seminal BBC television drama Cathy Come Home and forty-seven since Kes, Ken Loach may have made his most relevant, incisive and furious film yet – at the age of 80. Palme d’Or Winner I, Daniel Blake tells the story of a fifty-something joiner in the North East who finds him at the mercy of the welfare state after falling ill.

As we meet Loach, a man of quiet purpose, in the office of his production company Sixteen Films, we tell him that the end of our viewing of the film was marked by a room of stunned silence, punctuated only by very audible tears – many provoked by a scene in which single mother Katie, a companion of Blake in his battle against red tape, rips open a tin of beans in the local food bank, eating the contents with her hands in sheer desperation. Turns out this was no imagined scene: “It was a story Paul [screenwriter Paul Laverty] heard in Glasgow,” says Loach. “It actually happened”.

The food bank scene is definitely one of the most devastating moments in the film.

What we were concerned about was that once you know the story you want to tell, you have to be true to the people. You’ve got to be driven by their experiences, their relationships, how they are with their kids, so that it’s the people who drive the story. Because that’s when you connect.

Well, it puts the humanity back in the situation.

That’s what you hope to do. One thing you look for is the audience to feel solidarity with the characters, so they’re not ‘the other’; they’re not someone you can disregard because they’re less of a person somehow. Because the way the press writes about them, they’re something else. It doesn’t matter: they're scroungers, they're skivers, they’re benefit cheats. You see it all over the television programmes – it’s fascist TV, making objects of people who are vulnerable and poor and maybe had addictions in the past, so you make fun of them and they’re held up for ridicule. Solidarity is the one thing we don’t feel with them, so that was really important to us.

How do you tell those stories authentically?

It begins with the writing. Paul Laverty is a wonderful writer and we’ve worked together for a quarter of a century. It always saddens me that the director’s name is used in isolation, when it’s actually a collaboration. So it begins with a script and the research and being accurate but also allowing space for all human idiosyncrasies. Because you can be dead accurate and dead. It has to be full of life and quirks and funny things. It has to be full of all that. And then finding people that you really believe in. Like Dave [Johns, who plays Daniel Blake], he’s not only from Newcastle but that part of Newcastle we made the film in. So he’d walk down the street and people would know him and it beds it in a way. So there’s that and having everyone in it have a connection to either the place or something in their work or feeling that they are who they are.

Once you know the story you want to tell, you have to be true to the people.

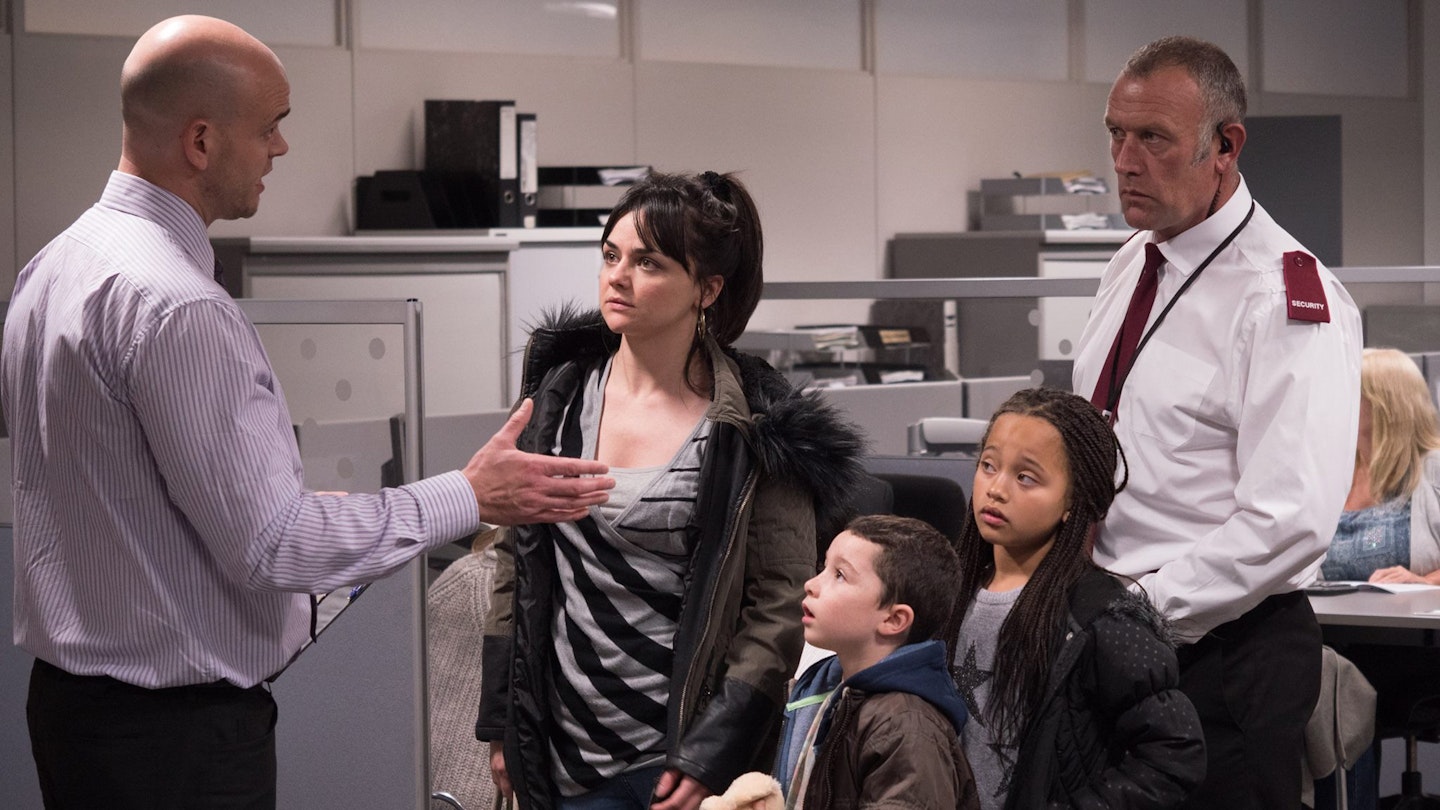

For example, in the job centre, there are two people who’ve acted before – they’re both experienced actresses – but all the other people are people who’ve worked for the DWP in the past and then left because they couldn’t stand the system and being forced to sanction. So in between takes, the two who were playing the parts were talking to the others. So you don’t have to invent anything. The people who are getting into the jobcentre are either currently or recently been in job centres. It just helps.

What about the women in the food bank?

They run the food bank! The woman who took her [Katie] round, she didn’t work in that food bank, but worked in another food bank, but she didn’t know she was going to do what she did [with the tin of beans]. So you get that spontaneous sense of horror. Surprise is something that’s very difficult to act. The instinctive timing is what gives the game away – if it’s really a shock, you have to absorb it before anything happens.

It had been reported that you weren’t going to make another feature film...

All that happened was that when we did Jimmy’s Hall, it was in Ireland and was a period piece and I was away from home a long time – the best part of a year – I thought, I can’t go through this again. Then some months later, you start to read stories and start to think again. This was a much more manageable little piece – logistically it’s very tight, we shot it in just over five weeks. It was fast, which I think is the best way to shoot, you keep the momentum going.

Your films deal with the realities of working class life. How important is it to tell the truth about what’s happening?

It matters whatever you do, in all different types of films – science fiction, space, whatever. You want to have some connection to some reality somewhere. I challenge the idea that films about rich people are escapism and films about working class people are dour and sad. I find the opposite’s the case. You meet real rich people and come away thinking: it’s such a depressing company to be with. They didn’t seem to have a sense of humour - or if they did, it’s disconnected to common experience. They lead lives of isolation and lack of connection.

[A script] has to be full of life and quirks and funny things.

I feel much more depressed than if you go to a place of work, where people are just knocking around being funny and connected. I don’t think films about working class people are sad at all; I think they’re funny and lively and invigorating and warm and generous and full of good things. Terrible things happen, but as an overall environment it doesn’t make you miserable. You might get angry, you might feel sad, you might feel angry on people’s behalf, but I don’t feel demoralised.

Are you surprised at where the British working class are now?

No, not at all. It’s the inevitable consequence of what Margaret Thatcher did and what Tony Blair did and Gordon Brown. They destroyed their industries, they tried to wreck their trade unions, they’ve allowed mass unemployment. They’ve had this punitive system if people are struggling. They’ve wrecked their schools, they wrecked their hospitals, closed their libraries, they’ve destroyed their youth work. Everywhere you look they’ve wreaked havoc – that’s widely Labour as well as the Tories – so of course, people are demoralised.

But what to me is a huge cause of hope is that nearly half a million people have joined Jeremy Corbyn to reinvent the Labour party. Despite all the hostile press, the hostile broadcasters – the BBC won’t run a story unless it’s hostile – despite that, there’s this huge wave of support and I think people know they’ve been cheated and they know they can live better. In a curious way, I feel more optimistic about possibilities now than two years ago.

I, Daniel Blake is in cinemas now. Pick up the new issue of Empire for a feature on the enduring relevance of Kes.