To sit in Jeremy Thomas’s office, a minute’s stroll from Tottenham Court Road tube station, is to take a pew in a glorious chapel to all things British cinema. The producer, a veteran of films both famous (Sexy Beast, Crash) and cult (The Hit, Mad Dog Morgan), has accrued enough photos, keepsakes and memorabilia to populate a museum that Empire would happily pay to visit. On one wall is the framed Best Picture envelope Eddie Murphy sent him after The Last Emperor’s Oscar triumph; on another, a Donald Duck cell signed “to Jeremy” by Walt Disney himself. There’s a model motorbike on a shelf, testament to an extra-curricular passion, and a snap with Dennis Hopper taken in the long-faded New Mexico glare. There’s an iPad on his desk although the VHS player, still in service after 30 years, would probably find a spot in that museum too. “It’s a classic,” he counters with a deadpan grin.

Loyalty and dependability have been hallmarks of Thomas’s career. His simple requirement for making a film hasn’t changed. ‘There’s no prescription for me,’ he explains. ‘It’s all based on: “Do I like it?” I do it because I like it. People find that amazing.’ With Ben Wheatley’s High Rise underway, he’s still finding plenty to like out there. This month he’s the subject of a BFI season showcasing some of the high points from his résumé. While he modestly defines his role as “putting together the bits” on a film, his instincts and command of filmmaking’s many complexities have guided his hand across four decades. Over coffee and Digestives, he shared some of his secrets.

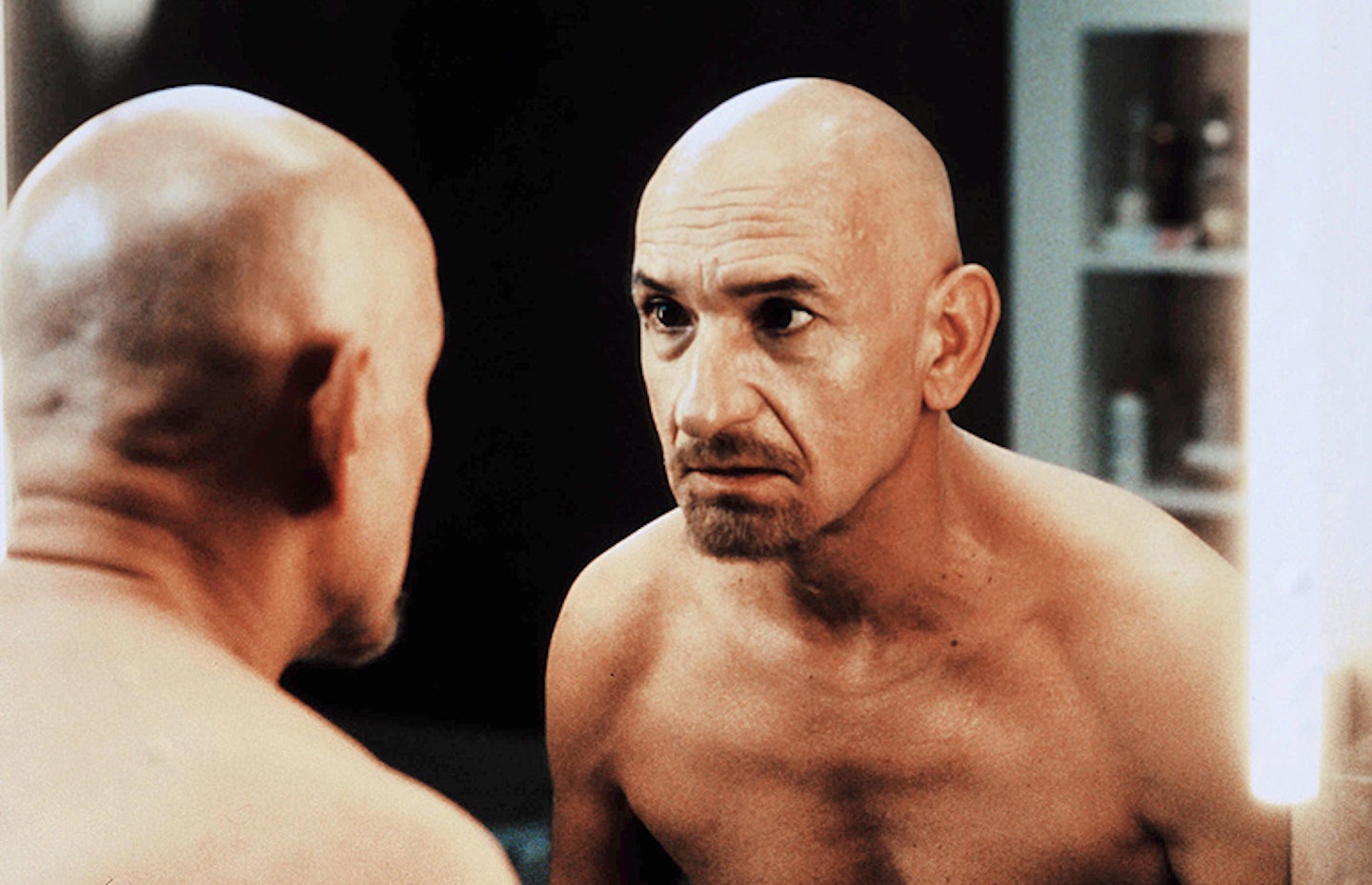

Sexy Beast (2000)

“I’m a filmmaker, a film lover, historian, archivist. All those years of filmmaking, it was the same thing going on every time: ‘This could be something, I like it.’ People find this fact amazing. ‘But what about the market?’ Couldn’t give a shit. The market will be there next year. I want my films to be successful but it’s not in the hard drive in selecting what I’m doing. It’s one of the components of the process, but it’s all based on your taste. I can’t think of another way of judging what project to do. When you decide to make a film with somebody, you want to make it with that person. Support it 1000 per cent in that vision. That’s how you make a film."

Kon-Tiki (2012)

“I loved the story of the Kon-Tiki expedition as a boy growing up in the ‘50s – it was a big story of six men on a raft across the Pacific – and I’d wanted to make it but (expedition leader) Thor Heyerdahl didn’t want to do it. A lot of people had tried to make it and he didn’t want to, even though his wife was keen. I made four trips to Tenerife to try to persuade him to give us the rights. It was a long courtship. I played The Last Emperor card – showing him that and other films [I’d made] – and finally he submitted. Maybe it was a certain time of his life and he was reflecting. Unfortunately, he died before it came out. Are there are other passion projects I’d like to do? There are lots of things, but I’m not going to tell you what they are. I haven’t tried South America as a continent and I’d like to make a film there."

The Last Emperor (1987)

“Food makes the world go round on a film set. You’re so absorbed when you’re making a film, you can’t do anything for yourself. You have to be looked after 100 per cent. One of my criteria is keeping the crew fed well so they feel better treated. As for restaurants, well, filmmaking is a very sociable thing and when you’re away from home there are a lot of restaurants involved. I first met Bernardo Bertolucci for The Last Emperor in Lee Ho Fook in Soho. You could get a bloody good char siu and rice for £2.50, although I might have pushed the boat out and gone for individual dishes. I was trying to impress him! He brought along this two-volume book, From Emperor To Citizen, and told me that he wanted to make it. I loved his films and he’d seen Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence and knew that I’d been to that place: somewhere difficult and exotic with a film crew. Then it was a question of making this huge, 60-year story into a film. But I was so drawn by it. It took four years, but it was very rewarding."

Eureka (1983)

“Eureka was an ambitious tableau of a man’s life in extremis. It has a man having his head hacked off and getting tarred and feathered – that’s every night on television! No, it was very intense. It was based on fact: Sir Harry Oakes, the Gene Hackman part, struck the largest gold strike ever and owned Paradise Island. One stormy night someone killed him in a way that looked like a ritual killing and no-one found out who did it. If you think of Charles Foster Kane or Daniel Plainview, they’re all relations of Harry Oakes. He’s an example of someone who finds everything and discovers there’s nothing left in life: “I searched for the gold and I found it but somehow the gold wasn’t all. That’s life.” Many people get Oakesed. Did I get Oakesed after my Oscar? (f_or The Last Emperor_) Maybe... maybe. It’s an affecting thing to have that in your life when you’re in your thirties. Yes, you can say in some sort of poetic way that it was a curse, but it’s better to have success than not."

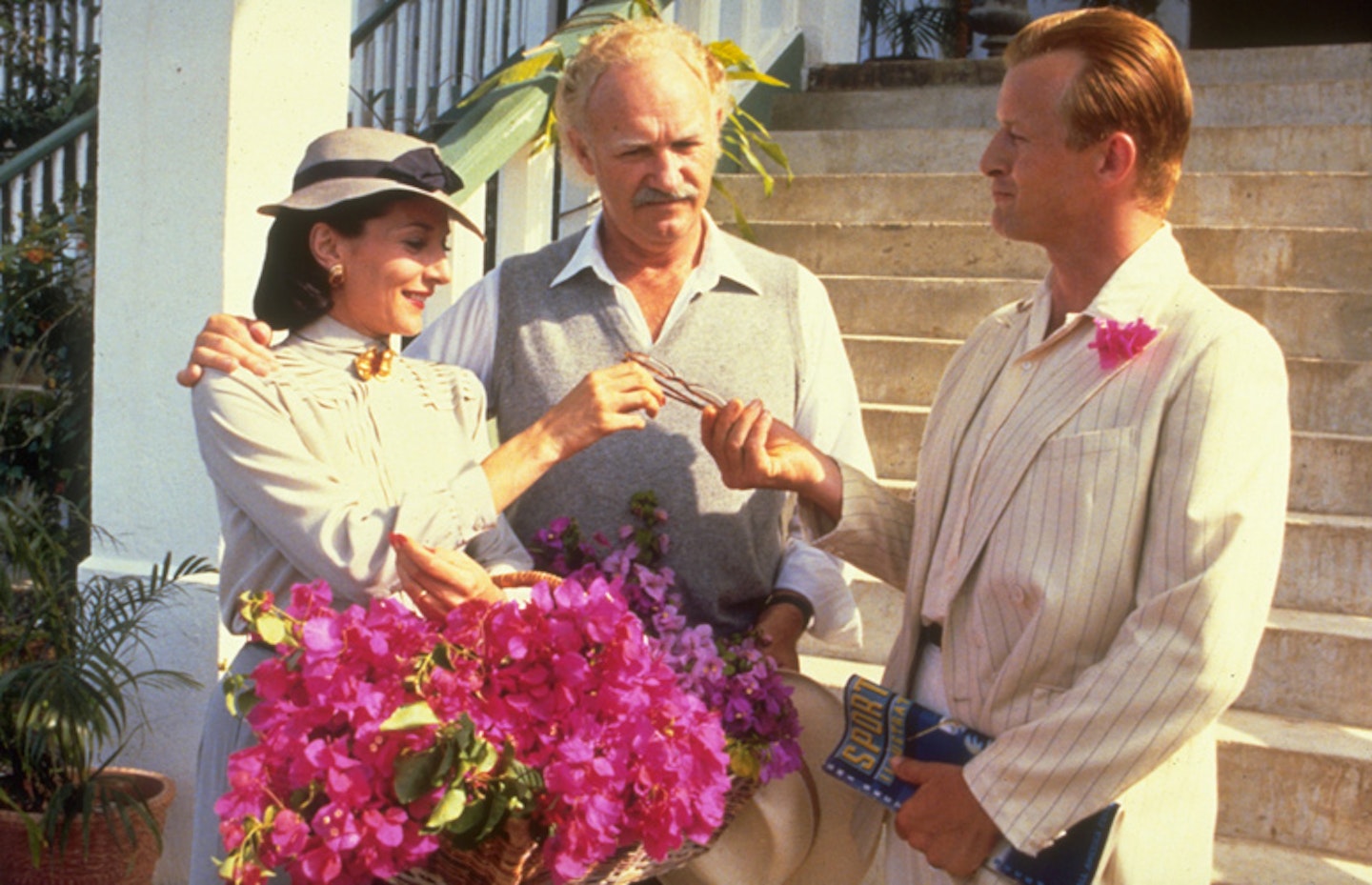

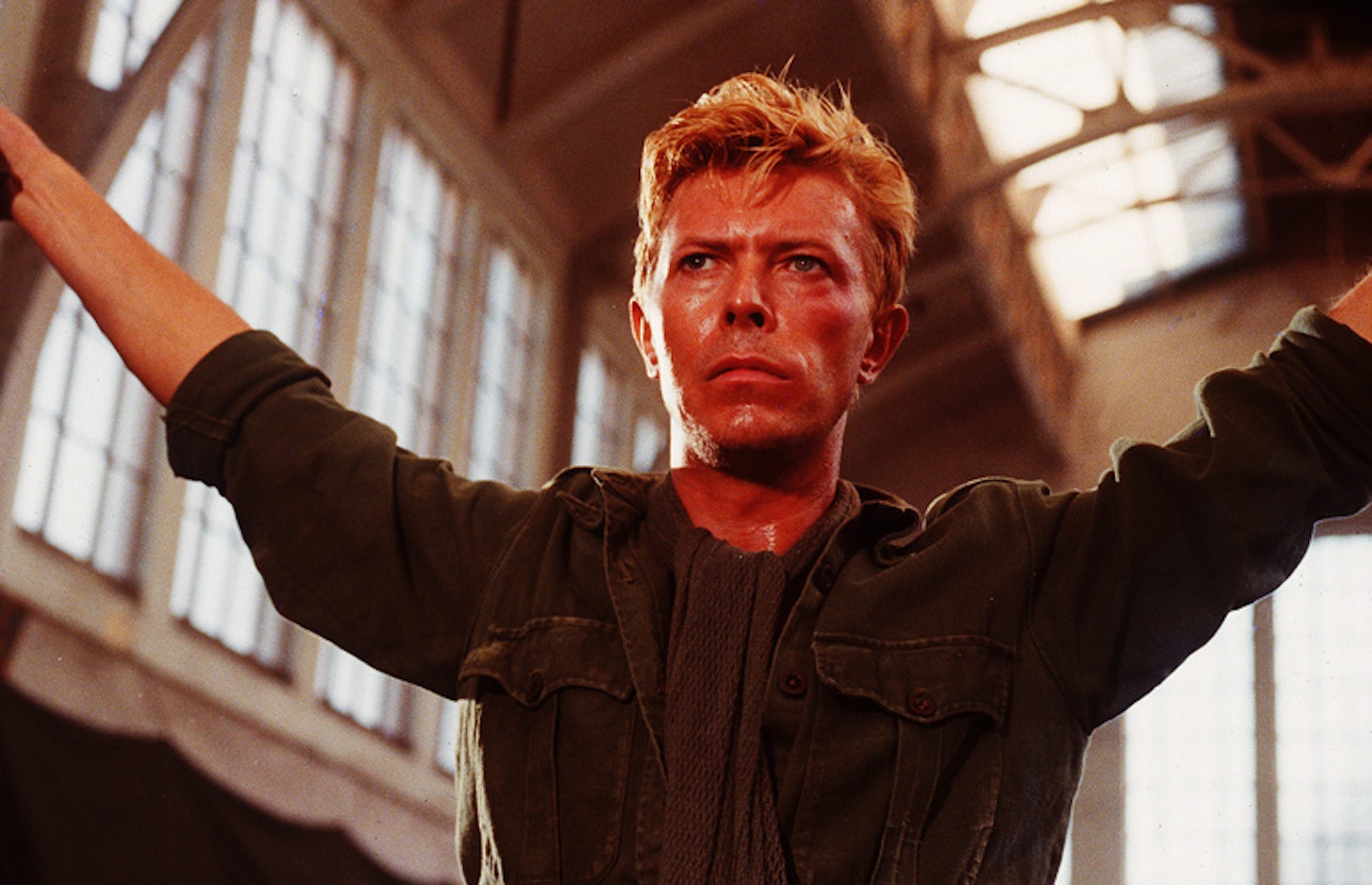

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983)

“We shot the film on the island of Rarotonga because of a New Zealand tax deal, and built the camp on a market garden in a valley that had some derelict greenhouses. The designer said: ‘I’m going to build a few huts with bamboo and the rest of the camp is going to be in construction in the distance.’ So what you think of as a huge prisoner of war camp is just a few buildings and a few carefully positioned four-by-two frames. (Director Nagisa) Oshima wanted a big space but we were a small movie and without visual effects we had to employ some trickery. We were very isolated on the island – one or two flights a week and no port – so the generators had to be brought in by lighters off the reef and everything else was flown in. But we had a great bunch of people – Takeshi Kitano, David Bowie, Tom Conti – and a half British and half Japanese crew. There was one hotel with 40 rooms. One town, one bar, a couple of restaurants… a simple place. I still hear Ryuichi Sakamoto’s theme music all the time. Have I heard the trance version{

The Hit (1984)

"During filming Tim Roth drove into £500,000 worth of camera equipment. He didn’t damage it, just the dolly, but the first question is: ‘Are we insured?’ You have to be insured on a film – there’s too many variables. But I spoke to Stephen Frears about this film recently and it was heaven. We had no responsibility: a group of like-minded people who were going across Spain in vans, stopping at places and filming. We had a great DoP, Mike Malloy, who’d worked with Kubrick and Nic Roeg. I miss that style of CineScoped-Panavision-old-cameras photography. All DoPs are artists, but the art of celluloid and chemicals and heating of baths and exposures, when you couldn’t fix it in post either, there was a special time. I always think of those moments around the camera at magic hour as very special. The Hit was filled with those moments. It was a very modest little film, made in five weeks with those actors in vans for £1m, but I love this film and I might remake it. I look through all the films that I’ve done and this one could be remade very well in America."

High Rise (2015)

"High Rise will be set in the ‘70s, just like the book. I’ve wanted to adapt it for ten years. I talked to Nic Roeg about it, but I talk about [J.G.] Ballard with everybody. Why Ben Wheatley? There’s many crossroads and junction points in every work of life, but especially in films, and I’d got stuck at a junction with this film when I got a message from my son telling me Ben Wheatley loved the book. My producer brain thinks: ‘What can this film be? With Ben directing and Amy Jump writing the script? That’d be good. I like it, I want to see it. We’re going to do it.’ People are amazed by that, but I can’t think of any way to do it. I can’t engage my brain in Spider-Man 5. Who would direct my Spider-Man? Wong Kar-wai."

Mad Dog Morgan (1976) / Only Lovers Left Alive (2014)

"When I went to meet Dennis Hopper for Mad Dog Morgan, he came to pick me up in a Jeep with his pistols. You can carry a gun in New Mexico as long as it’s visible, and he was firing it in the air in greeting outside the airport. The world’s changed since 1974! (Director) Philippe Mora and I were younger than him and he was a living legend and a hero: you couldn’t be more Hollywood, and he was the king of the counter-culture too. He had all the genuine trimmings of that with a shark’s tooth and cowboy boots and cowboy hat. We stayed for ten days and at the end of that he said he was coming [to Australia to the set]. The memories are a bit hazy now but there was a lot of drinking and partying. We watched The Last Movie several times in a cinema that was an old church. Dennis was a great artist.

"Only Lovers Left Alive was an irresistible film for me. The love of guitars and literature and significant cultural figures is worn on its lapel, along with its vampire legends that are thrown on their head. Jim Jarmusch and I are in the same boat: we’re both independent filmmakers. I’ve known him for years. I’ve worked a lot with Wim Wenders, who’s a good pal of mine, and Bernardo (Bertolucci), and you become intimate with these people."

“I could have been a little more profound [in my speech], but I just said, ‘Listen, independent cinema can be brilliant. There you go.’ I said it all. I was nervous sitting down but I didn’t feel nervous when I went up on stage. I feel terrible boasting about it, but I’ve made 30 or 40 films and it was only me. Nowadays you go up with the guy who knew the doorman - there are 13 or 15 producers. That’s the way you get films made these days.

"British Airways recently sent me a document listing my travels, and since 2005 I’ve flown 939,191 miles, been in the air for 11 weeks and flown to 47 cites. And I don’t just fly BA; I fly whichever airline’s cheapest. I’ve got a worldwide community of people I want to make films with, like Takashi Miike, [Nagasi] Oshima and Phillip Noyce, and I’ve got to travel. You’ve got to go to America all the time and Europe. It doesn’t even include Eurostar trips. I chill out on flights and watch everything. I just watched six hours of Breaking Bad, then there’s Lost, The Sopranos, Game Of Thrones... they’re all top-end viewing that challenges cinema."

Made In Britain: Jeremy Thomas is currently running at the BFI Southbank. Head here for screenings details.

Crash (1996)

“When I heard Crash had been banned in Westminster, I almost cut myself shaving. As a producer, you’re confused and amazed when that happens and you’re quickly protecting yourself, your film, your colleagues and your ideology. 80 per cent of my films are badly received when they first open, but that applies to many of my favourite films by Kubrick, Nic Roeg, Peckinpah, Orson Welles. Most of your favourite films are excoriated on opening by the critics but slowly [become recognised] over the decades. I’ve had a drubbing of my recent films. Don Hemingway wasn’t appreciated here, but it will be back. How can you not appreciate Jude Law’s performance? But you should read the reviews for Bad Timing, Naked Lunch and Crash. (Evening Standard's) Alexander Walker described Crash as ‘a movie beyond the bounds of depravity.’"