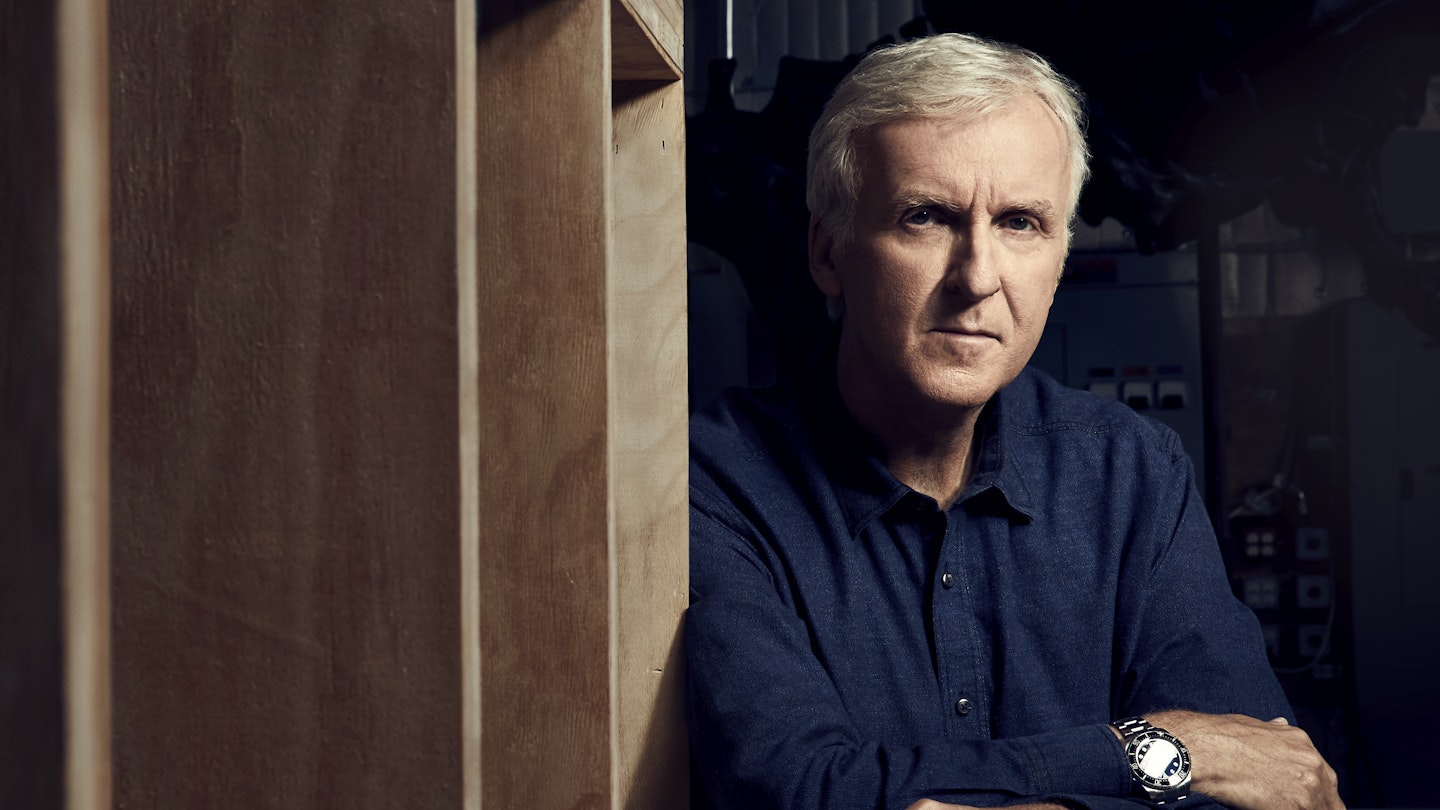

In 2019 Empire celebrates our 30th anniversary, showcasing the 30 most adventurous filmmakers of our lifetime. Kicking off this incredible line-up in the January issue is the first of our game-changers, one James Cameron. Empire’s Digital Editor-In-Chief and resident Cameron superfan, James Dyer, explains why.

When I interviewed for my first job at Empire back in 2000, the then editor — staring critically back over an expanse of black table — asked me to name the most visionary filmmaker in cinema. “James Cameron,” I said, without a second’s hesitation. Not Scorsese? They asked. Not Spielberg or Coppola? Hitchcock? Kubrick? Welles? No. James Cameron. King of the world.

Even at face value, this shouldn’t be a controversial statement. After all, this is the man behind the first and second most successful movies of all time, the ‘king of the world’ and undisputed box office ruler, whose reign has lasted 21 years and counting. But Cameron’s true worth isn’t found among his box office receipts (which currently run to a cool $6.1 billion), his Oscar collection (Titanic won 11, three of which reside at casa du Cameron), his record-breaking deep sea exploration (11km to the bottom of the Marianas Trench) or the Venezuelan frog that shares his name (Pristimantis jamescameroni). What sets Cameron apart from his peers is his frontiersman spirit: an irrepressible urge to push the boundaries of what’s possible and reach beyond his grasp. Limitations be damned. When tangible effects couldn’t match the fruits of his imagination on The Abyss, he demanded new effects, experimenting with so-called ‘CGI’ in a time when the notion was near science fiction itself. When 3D didn’t measure up to his exacting standards, Cameron developed new technology, fashioning the Fusion camera system that vastly expanded what was possible in stereoscopic filmmaking. When studio execs insisted he was about to make the biggest flop in movie history, he delivered the highest-grossing movie of all time. And, when his dream of Pandora and the Na’vi proved too ambitious for cutting edge effects, Cameron took the state of the digital art to a new level entirely with photorealistic motion capture and entirely virtual film sets that could be visualised in real time.

All of Cameron's movies are love stories first and foremost.

His entire career has been one of going his own way when everyone around him said he couldn’t. Forging ahead despite being told he shouldn’t. The result? Some of the most extraordinary, exhilarating, exciting movies ever seen. From the low-fi, guerrilla shoot that was The Terminator, to the slicker-than-slick visuals of Avatar, Cameron is a storyteller who understands the power of spectacle. But, crucially, that visual shock and awe is no substitute for heart. Beneath the high tech exterior, each and every one of Cameron’s films contains a human centre, with relationships, not action, at the heart of their stories. Whether it’s Titanic or True Lies, Aliens or T2 all of his movies are love stories first and foremost. Boy and girl, husband and wife, mother and surrogate daughter, son and cyborg father: each are built around an emotional core that elevates them far beyond their high concept loglines.

I had the privilege of spending an hour with Cameron last year to conduct a career interview surrounded by iconic memorabilia including the T-800, a 1:20 scale Titanic and the Alien Queen. My first meeting with Cameron, however, was a little more unorthodox. It happened over dessert in Wellington, New Zealand back in 2007. I’d spent the morning watching him put Sam Worthington and Sigourney Weaver through their paces on Avatar set. Having been told that he was very much “In the zone,” and unavailable for interview, the day had been billed as observation only. Efficient, methodical and entirely single-minded, just watching Cameron work was mesmerising for someone who spent his teenage years endlessly quoting T2. But it wasn’t until I impertinently positioned myself next to him in the catering tent for lunch, that I discovered ‘Iron Jim’ was far less terrifying than advertised. “This is good cheesecake,” I offered lamely, desperate to exchange words with the man himself. Turning to regard me, an unabashed fanboy in a Weyland Yutani t-shirt, Cameron (not yet a vegan) raised a cake-laden fork and inclined his head in agreement before extending a hand. Over the next 40 minutes we shot the shit, talking unhurriedly about everything from Na’vi underwear (they aren’t placental mammals so technically don’t need breasts) to 3D logistics (he had a special tent for watching rushes in 3D), his Battle Angel passion project (then still on the cards to direct), and, finally, the unparalleled genius of his third film and my greatest cinematic love: Aliens.

The 1986 follow-up to Ridley Scott’s seminal horror is among the greatest sequels ever made. As with Terminator 2, it takes everything that’s great about its predecessor, retains every touchstone a viewer could require, and builds that bodywork around a different engine entirely. Transitioning from isolation horror to a platoon movie or from a slasher-stalker to an explosive chase movie, Cameron understood that the key to following on from a classic is to evolve, not try to repeat. It’s this understanding of the cinemagoing mindset that makes the prospect of his Avatar sequel quartet so damned enticing. Onscreen or off, Cameron is not a filmmaker who repeats himself. His stories have evolved alongside the toolkit he has developed to create them, pushing boundaries, breaking barriers and driving forward with a singularity of purpose and a clarity of vision. He has expanded the scope of what’s possible, pioneering techniques that shaped the topography of the movie landscape and made the recent work of so many other filmmakers possible.

It’s been nearly nineteen years since that job interview and I still stand by my answer. Without Cameron, movies as we know them would not exist and I can think of no more deserving filmmaker to kick off Empire’s 30th year, nor to lead the list of 30 incredible directors who have influenced the course of Empire’s lifetime. Long live the king.