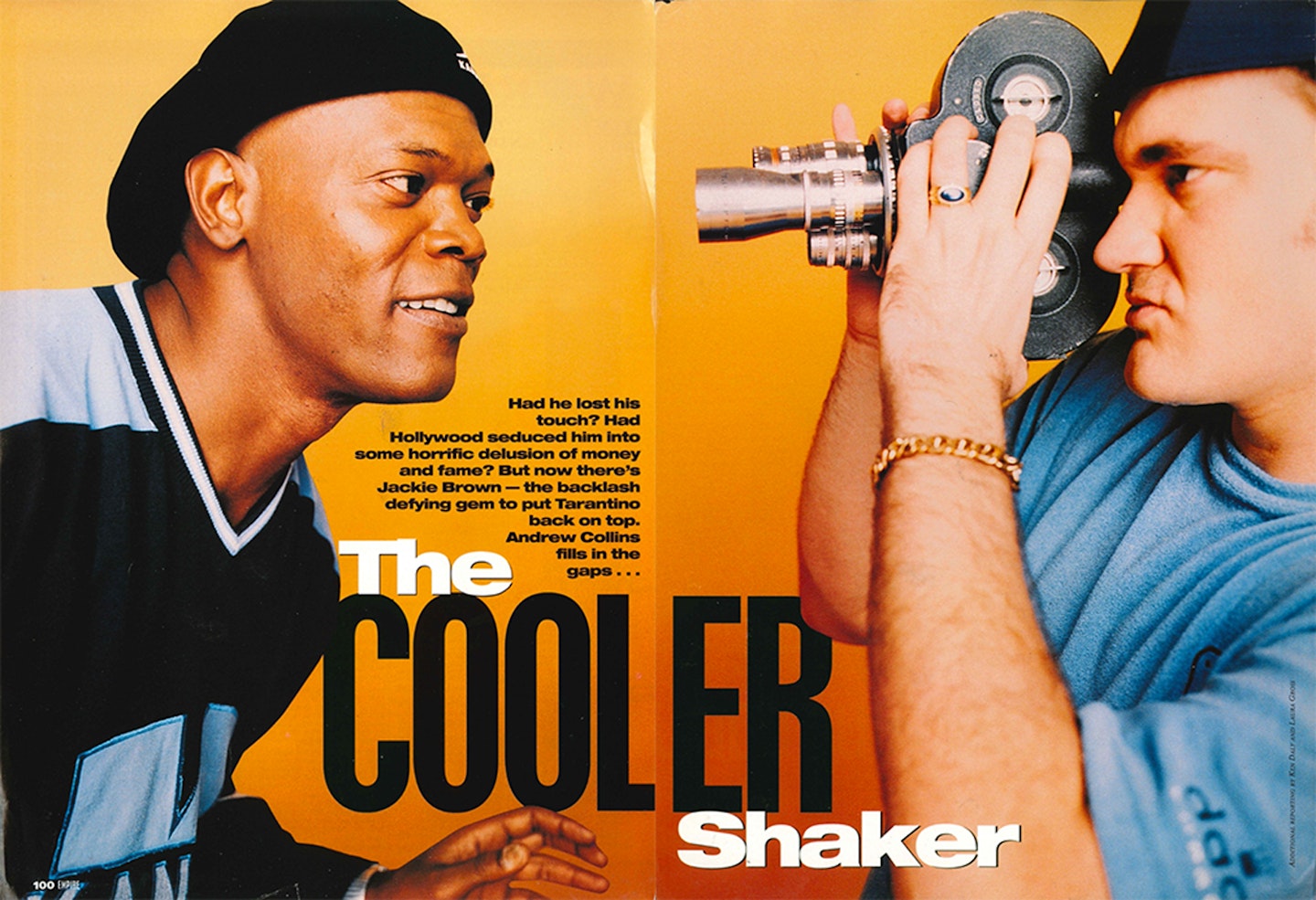

As Quentin Tarantino’s third film turns 25, take a trip back to 1997 when the follow-up to Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction was about to become a critical part of the filmmaker’s legacy. A longer version of this feature appeared in Issue #106 of Empire.

The Cannes Film Festival, May 1994. Miramax are holding a preview screening of Pulp Fiction at the Olympia Theatre. Quentin Tarantino mounts the podium to introduce it. Doing his best Butlin's redcoat, he asks the crowd, "Who liked Reservoir Dogs?" There is wild applause. "Who liked True Romance?" More applause. "Who liked Remains Of The Day?" The odd clap. To which Quentin responds, "Get the fuck out of this theatre!"

When, at the festival's climax, the jury subsequently awards Pulp Fiction the hallowed Palme D'Or and its director hops up to receive the gong, there is a lone jeer from the dark. He responds to this anonymous detractor with what Americans know and cherish as "the finger".

Punk rock! He even wears a ring with the symbol for "anarchy" on it (mistaken by one US journalist for the Star Trek Federation logo). Swearing in public. Trashing snooty period dramas. Internationally-recognised hand gestures. The epithet enfant terrible was placed around Quentin's neck by the media after Reservoir Dogs: after all, he was 29, he'd made a film with blood and swearing in it. That's terrible enough for most of the media.

This hotshot writer-director also had the neck to cast himself in his first two films, as Mr. Brown in Dogs (a lesser pawn in the heist, but he does open the film), and as Jimmie in Pulp Fiction (again minor). Quentin Tarantino was visible; he made himself thanklessly available to promote both films, worldwide ("I did interviews with everybody, everywhere. I would arrive in a country unknown and leave known"); when Faber And Faber published the screenplay for True Romance in 1994, they put a goofy picture of Quentin on the cover, not a still from True Romance – that was the extent of his media profile. A director! James Cameron, Tony Scott, Curtis Hanson, Paul Verhoeven, even a grandmaster like Sidney Lumet – they could all stand in Menzies thumbing through their own books and not be recognised. Tarantino, now 34, is a star, and has been for five years. But is he so terrible anymore?

He lives in a palatial mansion high in the Hollywood Hills previously owned by MOR singer Richard Marx, he has guest-directed ER and has guest-hosted Saturday Night Live, and furthermore, his latest film is a calm, largely non-violent study of middle-age. He's a starmaker. He's a Guardian Lecture. Tarantino is Establishment.

It's a considerable evolution from Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction.

Which leads us to the question: is Quentin Fuckin' Tarantino really so great?

To quote, perversely, Stevens the butler from The Remains Of The Day, "There will always be those who would claim that any attempt to analyse greatness is quite futile. It is surely a professional responsibility for all of us to think deeply about these things so that we may better strive towards attaining dignity for ourselves."

Right on. If we judged Quentin's Greatness by his first two films, then yes, he is right up there. In the writing alone, Dogs and Pulp reveal a master of the art, a fine-tuned pair of ears with a pen, and a gifted comedian. If we judged him by his quarter of Four Rooms, we might say he was a hack (old story, perfunctorily told). If we judged him by his acting (Sleep With Me, Destiny, Desperado, From Dusk Till Dawn), we might say he was a one-trick pony, good at playing a drug-dealer version of himself, interesting forehead.

He doesn't appear in Jackie Brown (a "conscious decision") while those who do – Samuel L. Jackson, Robert De Niro, Pam Grier, Michael Keaton, Robert Forster, Bridget Fonda – confirm once and for all that Quentin is an actor's director not an action director, teasing fine, affecting performances from the lot of them. Jackie Brown is an essential milestone for the auteur nouveau whose previous two films defined the movie decade (Pulp Fiction was voted Greatest Movie Ever by Empire readers in 1996; Dogs, number three).

One, it's brilliant – "a connoisseur's crime movie" said the Chicago Tribune when it opened in the US on Christmas Day; "A symphony in the key of cool," declared the Washington Post – and it gets Quentin over what's known in rock music circles as the Difficult Third Album. Two, it's a considerable evolution from _Dogs_and Pulp, despite the LA-based crime-caper story: its characters are significantly older and slower, and those who inaccurately see Quentin as master only of violence and sensation, will have to shut up.

"It's more mature," reckons producer Lawrence Bender – and the dapper, Bronx-born former flamenco dancer should know: he's produced all three of Quentin's films. "It's similar to Pulp Fiction in that people go some place jn a car, and then they go some place else in a car, but Pulp was more showy and in your face. There's a tenderness to this movie."

In Hollywood terms, Jackie Brown only cost a few dollars more than its predecessor ($12 million to Pulp's $8 million), and supports Bender's notion of Quentin as "a very responsible filmmaker. He prides himself on bringing his movies in on schedule, on time and on budget." Once Reservoir Dogs had made Quentin a star, he began returning the favour to his heroes, insisting on a shop-soiled Travolta for Pulp (he's now worth $20 million a picture), gift-wrapping Jackie Brown for obscure 1970s blaxploitation icon Pam Grier, then casting 56-year-old Robert Forster, most famous for playing 1970s TV detective Banyon, in the key role of bail bondsman Max Cherry. All are eternally grateful.

"It is difficult to believe that someone would write a movie for you. He could've written it for anyone," exclaims Grier, clearly relishing her own revival, and, at 44, truly looking the part. Forster says he's "thrilled and astounded" by his second chance: he didn't even have an agent when Quentin shoved the script under his nose (he'd auditioned for Lawrence Tierney's part in Dogs, and Grier had tested for Jody in Pulp, which went to Rosanna Arquette, but a mental note had been made). Neither actor is backward in coming forward when the time comes to Praise Quentin!

"He goes at 100 miles an hour. A dynamo. This guy is old beyond his years. He's nice to everybody," coos Forster, favourably comparing him to the late great John Huston (with whom Forster worked on 1967's Reflections In A Golden Eye), "Both heavyweights, titanic guys."

Grier ascends into poetic eulogy talking about the script: "His characters jump off the page, you can smell them. You can feel them. You walk into a room, you can feel the smoke in the air, you can feel the breeze coming through the room, and what kind of tree was outside the room when the breeze blew through the tree and came in the room..."

Elmore Leonard, from whose 1992 book Rum Punch Jackie Brown is adapted (he enjoys an executive producer credit on the film), also approves of the final product. "You get to hang out with my characters," he commented, after viewing it for the first time.

The critical tide, which looked so much as if it was drifting in the opposite direction after Four Rooms, seems to have turned Quentin Tarantino's way again. As The Guardian almost grudgingly put it: "Just when the powerbrokers were beginning to think they might erase him from their powerbooks, he's done it again."

Quentin Tarantino has re-entered the building. Time for alt-culture's prodigal son to get out of character...

EMPIRE: If you're still intent on being an actor, why didn't you cast yourself in Jackie Brown?

Quentin Tarantino: I was very proud of the work I did in From Dusk Till Dawn, and I was a little precious about it. I wanted to follow it up with something equally worthy. There wasn't really a role for me in Jackie Brown – and I have integrity that way, alright? I wasn't trying to put myself in the movie or put in a fun cameo for the heck of it. People have been taking me for granted a little bit, so.

Did you intentionally tone down the violence in this film?

You have to remember, probably the number one scene that people would say I've done, would be the torture scene in Reservoir Dogs, and you don't see the ear being cut off. Me showing violence off-screen or in long shot is part of my cinematic style. You never saw the head explode in the back seat of the car (in Pulp Fiction) either. You see the aftermath, you never see a close-up. I no more intentionally toned down the violence in Jackie Brown than I did intentionally heat the violence up in Pulp Fiction. Real-life violence explodes in a flash of a second and is over just as fast – you witness it out of the corner of your eye, and you're like, "What happened? Did that guy just get shot?".

Did you feel under pressure to follow up Pulp Fiction?

I never felt any pressure about following up Pulp Fiction. People don't believe me, but I didn't, alright? People assume that I wasn't following it up immediately because I was intimidated or scared by it – there's something really insulting about that to me. I've tried to build a career that's been completely based on no fear, and I truly don't fear anything artistic. I fear a guy in an alley with a baseball bat, I fear the Manson family bursting into my house, I fear a rabid dog walking down the street, but I don't fear anything artistic. And if I did, then good, that's a great thing, that's a rocket. I didn't feel any pressure, but do you know what? I'll be honest, I might've done if I wasn't a writer. If I was David Fincher and I'd just directed Seven, I would imagine I'd be reading a zillion scripts, trying to find what I wanted to do next, and I'd probably find nothing worthy of doing. Apparently Scorsese had that after Taxi Driver. But luckily I don't have that. Paul Thomas Anderson doesn't have that. You always start with the material.

Talk us through the process of adapting Rum Punch…

I equated it with editing. I've always equated the editing process with the writing process. I had to find my two-and-a-half hour movie inside of a six-hour movie. I had a lot of questions for Dutch (Elmore Leonard's nickname), and he was a dream. When I'd say, I've gotta drop this, he'd say, "Hey, it's your movie. Go off and do your movie, I can't wait to see it."

You did a lot of shooting at night. How did you keep the cast and crew from falling asleep?

We learned this from Tony Scott actually ... When you're doing a night shoot, people have a tendency to doze off. We found out that Tony Scott would put a rubber penis next to them while they were asleep, and take a Polaroid of them, and that would keep everyone awake. I sent one of the interns down to Santa Monica Boulevard, and I said, "Get the biggest dildo they have." And it was about the size of a lamp in a living room. We called him Big Jerry. He became a very, very important member on the set. Lawrence (Bender) was the one who got into it the most, he would sneak up on people. We kept a big collection of the pictures, but we decided for safety we'd burn them at the wrap party, the whole Big Jerry Gallery.

Do you ever get nervous when you're working with someone like De Niro?

It's funny. The answer to that is no. I had kind of gotten to know Robert a bit before we actually made the movie. From an acting standpoint, I'm as proud of Louis (De Niro's crumpled ex-con character) as any character I've ever written. As opposed to what people expect from my characters – great dialogue, great monologues – he doesn't have that. That's not who he is. It needs to come across through body language, by the way he sits in a chair. I remember describing to Robert that I saw his body language like a pile of dirty clothes. Well, I just happened to be talking to one of the greatest actors that has ever been produced when it comes to characterisation through body language, and he knew exactly what I was talking about. Every once in a while you get that moment – it's not fear, it's not nervousness, it's just wonder. It's, "Wow, I'm directing De Niro!"

———

"Quentin Tarantino is from another planet. He's a Martian," reckons Pam Grier, referring to Dr. John Gray's book Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus, the self-help relationships guide that builds on the intrinsic differences between the sexes and offers 101 Ways To Score Points With A Woman, such as, "Offer to build a fire during winter", "Leave the toilet seat down", or "Give her a foot massage" . And we all know where that leads.

When all's said and done, at the remains of the day, Quentin's as close to an ordinary guy as his huge wealth, phalanx of "people" and world-beating fame will allow. He and Grier "hang out", she's proud to tell us, "We're just Pam and Q." They shoot pool, shoot the shit and eat Mexican food – but he'll never let her pick up the check (Martian trait). As for the pool table, "You've got to watch him, he'll move a ball if you turn your head!"

That's precisely what he's done with Jackie Brown: moved the ball, while we were busy criticising his acting and valuing his house. He's re-defined "Tarantino-esque", cauterised the backlash for another couple of years, and resurrected the careers of more ‘70s almost-rans ("I'm back in business!" exclaims Robert Forster, triumphantly). His distributors, Miramax, still claim to be "in the Quentin Tarantino business".

Skip to the last page of Rum Punch, where Max Cherry describes his job as "dealing with scum, and trying to act respectable". With Quentin, it's the other way around.