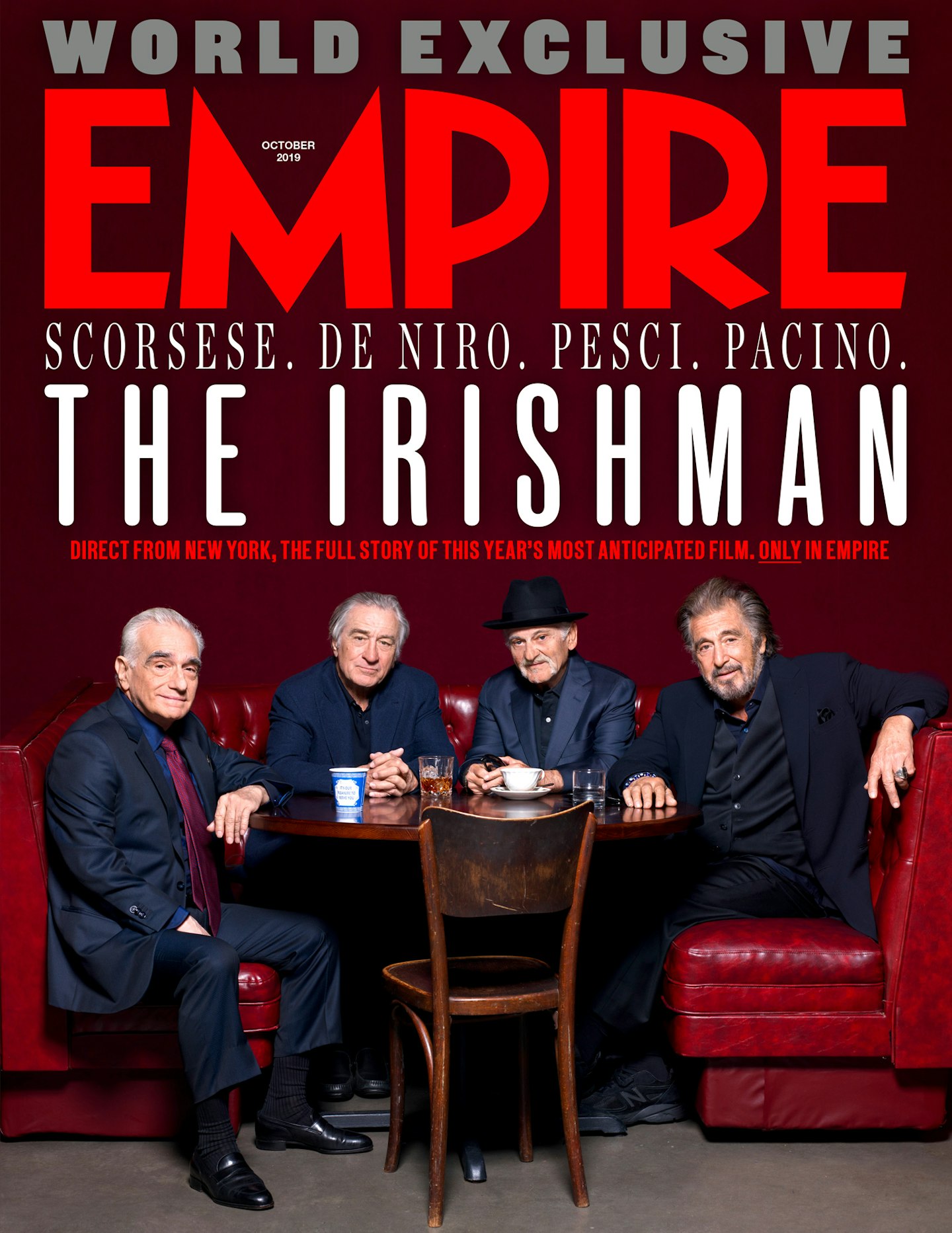

In the run-up to The Irishman arriving in UK cinemas, Empire Online presents The Irishman Week – a series of features to get you ready for Martin Scorsese's latest gangster epic. Here, we present Empire’s recent world exclusive interview with the filmmaker himself – one of the undisputed all-time greats.

Earlier this year, Empire was granted a career-spanning interview with Martin Scorsese – an expansive conversation covering his days growing up in 1940s New York, the years where he struggled to get movies made, and the time he was directed by Akira Kurosawa. And yes, he did mention Marvel – in response to a question about de-ageing techniques – but he also talked about so much more. Read the full interview.

It was late 2005, and Martin Scorsese had just decided to go rogue. His new film, The Departed, had wrapped after a lengthy, arduous shoot, and Scorsese was being hounded by Warner Bros. executives to unveil a cut. So the filmmaker and his editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, sat down in their private screening room, part of his office complex high up in the Directors Guild building on New York’s 57th Street, to find out where they were at. The Boston-set crime drama unspooled in full. Then Scorsese turned to Schoonmaker and told her they were starting the whole thing from scratch.

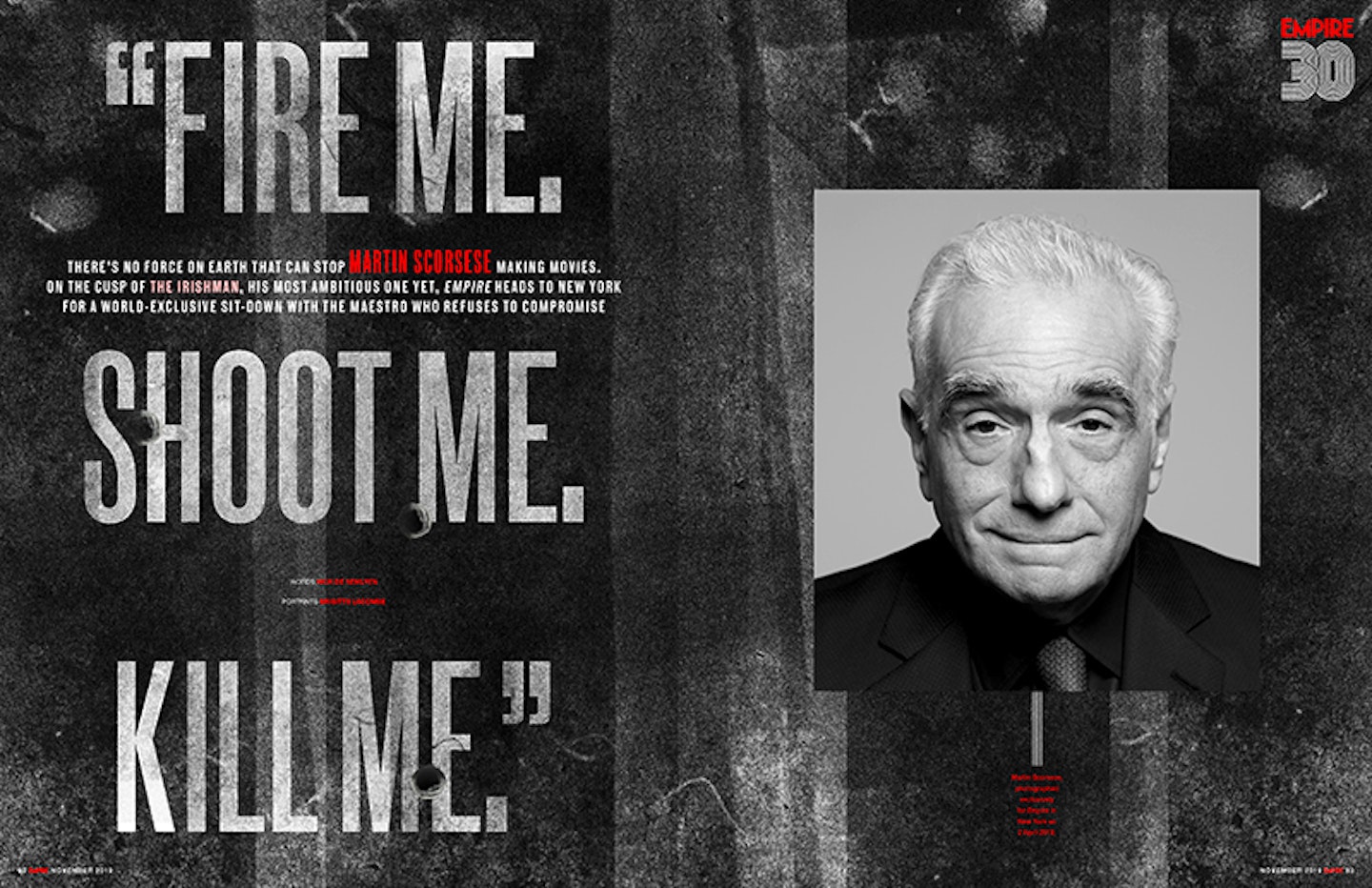

“For six weeks, there were literally people out there knocking on doors,” the director recalls now. “We wouldn’t answer it. They were really mad at us. They really were angry. I said, ‘Fire me, shoot me, kill me — we’re gonna wrestle this thing to the ground.’”

Fourteen years on, Scorsese has welcomed Empire to Sikelia Productions, the place that was previously a siege-ground, for a lengthy sit-down chat. His HQ is, as one might expect, a hushed haven and a serene shrine to cinema. Sir Christopher Frayling’s new book on Once Upon A Time In The West has just been couriered over, ready to join the many other dense tomes filling the shelves (yes, Scorsese owns Scorsese On Scorsese). Antique Sicilian puppet knights dangle from hooks. And many, many immaculately framed film posters line the walls. But it’s perhaps telling that the two on the wall directly behind his desk — Sunset Boulevard and The Bad And The Beautiful — are both tales about the dark side of Hollywood, tales which demonstrate that filmmaking is not a world for the faint-hearted.

Over the years, Scorsese has garnered much success and even more acclaim. The Departed, of course, went on to finally win him that long-deserved Oscar. But none of it has come easy. In pulling off one hugely ambitious, seemingly uncommercial victory after another, he’s had to make hard decisions and hold his nerve. No matter how many people were knocking on his door.

•••

In his formative years, Scorsese wasn’t quite so tough. Born in the relative tranquility of Flushing, Queens, at the age of eight he suddenly found himself engulfed in the madness of Manhattan’s Little Italy when his parents, experiencing “problems with the landlord”, moved back to their old neighbourhood. “It was very difficult for them, and also for me, because I had been a kid with terrible asthma who was taken care of all the time, and then suddenly thrown into hanging out with the Dead End Kids,” he remembers. “Playing with garbage pails and jumping over the poor alcoholics who were dying in the street. Chasing rats — that was big.”

It was a shock to his system. ‘Devil’s Mile’ (the Bowery) lay east, ‘Murder Mile’ (Mulberry Street) lay west — neither sounds particularly inviting for a stroll. Crime was rife, not least from the underworld figures who ruled the streets. “The streets were anarchic: there was control but almost like a medieval kind,” Scorsese says. “If you knew to behave respectfully to certain people, it was cool. If not, there were problems. You behaved within those parameters, unless you were some kid who thought he could take on the world, who usually ended up dead.”

Young Marty had two favourite spots, both well away from the chaos. One was the local cathedral, St. Patrick’s: “I lived in there. It was peaceful and it made sense.” The other was the fire escape of his family’s third-floor apartment at 253 Elizabeth Street. He would sit there for days on end, looking down, following the most interesting people and directing movies in his head. “I saw so many things from that fire escape,” Scorsese says, wistfully. “So much imagery, so many incredible spectacles. Laughter, fights breaking out, the butcher running out with a bat. You could just pan up and down the street.”

All this observing made him an astute student of human behaviour, but also a frustrated one. He’d mimic his favourite actors in the mirror, but in reality he couldn’t even run, thanks to his asthma, let alone perform the kind of heroics he loved watching in movie theatres. Finally, though, he found a creative outlet: filmmaking. And in his breakthrough third picture, 1973’s Mean Streets, set on his home turf, all that pent-up energy came bursting out. “There were a lot of things I couldn’t say or do that expressed themselves in that film,” he confirms.

At the time, Pauline Kael called Mean Streets “a triumph of personal filmmaking”, with “a high-charged emotional range that is dizzyingly sensual”. Watching it now still feels like being jolted with electric current. Scorsese takes us on a tour of a place where comedy and horror jostle side by side, his camera diving into edgy pool halls and sordid bars, navigating the underworld with a confidence the director never had before he picked up a camera.

In Taxi Driver, a few years on, his home city looks even more hellish. Scorsese denies that this was by design. “For me that was normal in New York,” he insists. “We didn’t think of it as a terrible place. When President Ford said to the city, ‘Drop dead,’ or whatever, we were kind of shocked. The city was falling apart, but it was falling apart in the late ’50s and all through the ’60s. It’s like what’s happening now, where new norms are being formed in terms of democratic process here in America. It’s a slow erosion, and you live with it. When a city starts to erode, that’s on many different levels. You could see it in The French Connection. You could see it in Taxi Driver. Those two films, I think, give a real sense of what it was like. You can almost smell it through the screen.”

No filmmaker and city are more synonymous than Scorsese and New York. His new movie, The Irishman, will return to the Copacabana Club, home of GoodFellas’ iconic Steadicam shot, for a scene involving insult comic Don Rickles (played by actor/comedian Jim Norton). Yet he sounds melancholy when he considers what the city has become. “I must admit it’s safer, and that’s good. I don’t miss the way 42nd Street was when we shot Taxi Driver — it was horrible,” he says. “However, it’s just as horrible now. Only you can bring the kids. Let them enjoy the mind-eviscerating horror!”

•••

The 1970s was the perfect climate for Scorsese’s ascent. The type of film he liked to make — personal, emotionally raw, audaciously original — was in vogue, with studios willing to finance experimental endeavours. Commercial success was an afterthought. “We didn’t care,” Scorsese states. “I don’t mean to be arrogant, but I never thought of that. I knew that it wouldn’t translate for everybody. But there’ll be some people in the audience who’ll say, ‘Yeah, that’s me.’ And maybe it’ll make your life a little richer.”

For a while he could do no wrong. He followed Mean Streets with a female-led drama, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, which won star Ellen Burstyn an Oscar. Taxi Driver picked up the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1976. Then, at the tail end of the decade, he decided to make a modern spin on the MGM musical New York, New York. And his world came tumbling down.

Despite featuring another collaboration with Robert De Niro, and allowing Scorsese to pay homage to the Golden Age of Hollywood, the film was a disaster, with an out-of-control shoot and poor box office. The director became depressed, exhausted and hooked on cocaine, ultimately collapsing and nearly dying from massive internal bleeding.

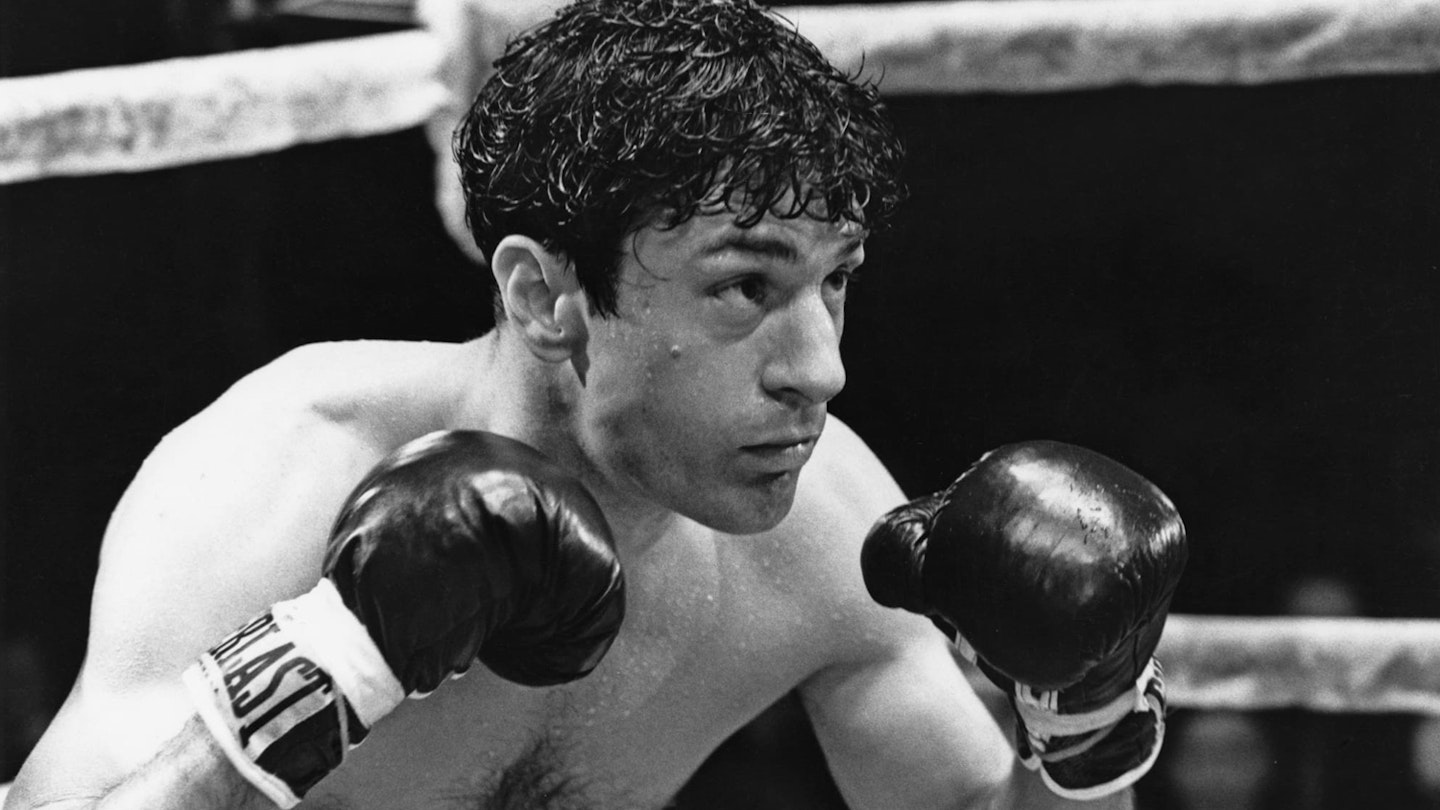

It seemed he had flamed out. But De Niro convinced him to make one more film: Raging Bull, a dark psychodrama about a boxer that, like Mean Streets, could allow Scorsese to pour in all of his pain. It worked. “I made it as if nothing else would happen after. Just burn everything down with it, you know?” Scorsese says. “Raging Bull, once I caught on to what it could be, then I knew I had to put everything of myself into it that was possible.”

While the result was a masterpiece, it heralded the beginning of a difficult decade. “In the ’80s nobody would even talk to me,” he says. “I couldn’t get into a meeting, basically. The King Of Comedy was De Niro and I trying different things. Tightly controlled frames where there was very little camera movement; it was the opposite of what I had done in Raging Bull. But it was the flop of the year, they claimed in America. Except the British — you got it.”

The new Hollywood was safer, less up for a risk. Scorsese failed repeatedly to get his passion (and Passion) project, The Last Temptation Of Christ, off the ground. And not even the combined might of he and Al Pacino could get a biopic of painter Modigliani off the ground. “It was about the extraordinary struggle to create art. The sadness of it, the absinthe,” Scorsese says of the film he ultimately had to abandon. “He and [his companion] Soutine taking care of each other, with her convincing him to brush his teeth. It really would have been something special, I think. But someone who was a big producer in Hollywood said to my face, ‘You’re washed up. Where are you going to get the money to do it?’ I didn’t have the influence anymore. I was from a certain period — the world had changed and you just weren’t bankable, as they say.”

He hung in there, refusing to give up on his own extraordinary struggle to create art. It was The Color Of Money, in 1986, that started to turn things around. On the surface it was the most un-Scorsese-like of gigs — a sequel, a star vehicle and a film about pool sharks (it’s hard to imagine the director of Silence unleashing a 9-ball thunder break). But he saw it as a challenge, a way back to the top. “Could I move quickly? Make something with a Hollywood star, on a short schedule?” He even used a payphone on set, queuing up with everyone else, as a gesture of frugality. “Color Of Money came in a day under, and a million dollars under,” he says. “It showed a responsibility to the nature of the business itself. Even if it’s not my favourite of the work I did. I wanted something deeper, you know?”

He got the chance, and then some, with his next two movies: The Last Temptation Of Christ, at last, and GoodFellas. One followed the Son Of God, the other a coke-addled mobster named Henry, but each is, in its own way, a profound study of good and evil.

As GoodFellas wound down, however, the director faced another crisis that tested his steel. “We went over schedule, about 15 days over, and the studio was furious,” he recalls. “We were treated very badly; they even refused to give a little wrap party.” Making matters more stressful: as he finished off his mobster epic, Scorsese was awaited in Hokkaido, where he was supposed to be shooting a cameo as Vincent van Gogh in Akira Kurosawa’s film Dreams.

“I was 15 days over, Kurosawa was waiting, all these angry guys are visiting the set — everyone’s mad at me!” Scorsese recounts with a grin. “I was so nervous that my doctor told me I had to stop drinking coffee.”

At last, the final shot in the can, he hopped on a flight to Japan. And what was it like being directed by the iconic creator of Seven Samurai? “Not a lot of laughs!”

•••

Scorsese would seem to be walking, talking evidence that the Tarantino Theory —which posits that directors lose steam once their output hits double digits — is off the mark. He’s currently gearing up for Film 26, Killers Of The Flower Moon, a saga of Native Americans, lawmen and villains in 1920s Oklahoma that will bring together his two muses, Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio. “It’s an incredible story, so rich,” he says. “But one has to find the right point of view to tell it.” He’s also pondering a biopic of Theodore Roosevelt that could star DiCaprio. And that’s not including his many documentaries, the latest of which, a celebration of the Canadian comedians of Second City Television, is currently being cooked up in the “closet” next door. That old Scorsese curiosity is still aflame — he remains as fascinated by people of all stripes as he was as a boy, peeking down from that third-floor fire escape.

Over the past 30 years, he has hurtled from project to project at a rapid clip, as if anxious he might return to that time when he couldn’t get into a meeting. His movies have featured the Dalai Lama, businessmen on Quaaludes, ambulance drivers, Jesuit priests and Jack Nicholson wielding a dildo. He’s dabbled in 3D for Hugo (“It’ll be back,” he insists), deployed a CG elephant in Gangs Of New York, and is pioneering extensive de-ageing technology in The Irishman (“The risk is scary, but I had no choice”). He’s even shot a scene, for Casino, in his least favourite environment on Earth: a golf course. “It’s the worst location,” he grouses. “I’ve been on mountains. I’ve been in deserts in Taiwan. Dealing with typhoons and earthquakes? Fine with me. Golf course — no! I’m allergic to everything, and I die.”

His unflagging enthusiasm remains fuelled by the work of others. During our conversation, inspired by Empire’s Britishness, he waxes lyrical about Basil Fawlty (“With Basil, one has to genuflect”) and a “hysterical” Goon two-reeler called The Case Of The Mukkinese Battle-Horn. There is a Scorsesian blizzard of directors’ names (Ozu, Mizoguchi, Renoir, Bruce Beresford), while he extols the calming qualities of Romanian cinema. He keeps up to date with new releases, too, enthusing about Midsommar. “The editing, the camera moves — glorious! And the image of her in the flowers? My God!”

The only time his ardour dims is when the subject of Marvel comes up. “I don’t see them,” he says of the MCU. “I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well-made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

Which is not something anyone can say of his own work. And while he may be 76 years old, he’s not done creating experiences yet. “I thought a few years ago I could stop, but I don’t think so anymore,” he says. Then he laughs. “Look, what do you want me to do — be 100 years old and making Roosevelt? You’re going to have me coming in, giving me oxygen while I shoot!”

A centenarian Scorsese, still pointing and shooting, 25 years from now? Well, this is the man who’s survived the mean streets of Manhattan, enough drugs to kill a raging bull, and Shark Tale. Don’t rule it out.

READ MORE: The Irishman Week: Robert De Niro Q&A

READ MORE: The Irishman Week: When Empire Interviewed Joe Pesci

Read Empire's world exclusive Irishman issue, available digitally via the Empire Magazine app on the App Store and Google Play.