With the arrival of Tenet now imminent, Empire Online is celebrating with Nolan Week – revisiting the films of an iconic contemporary director. While Inception is widely considered to be Christopher Nolan’s greatest work, Empire’s Ben Travis argues that another of his original epics is more deserving of love.

One of Inception’s most pulse-pounding action set-pieces takes place at a towering snowy fortress. It looks alpine, but it’s actually the third level of a series of dream layers – a dream within a dream within a dream. Boasting a ski-slope shootout, gun-toting snow-speeders, and a massive explosion-turned-avalanche, it’s breathlessly exciting stuff, a brain-bound Bond sequence – and yet, for all the thrills, it strikes at the very thing that I struggle with when it comes to Inception. Like that mountaintop lair, it’s grand and impressive – but also icy and impenetrable.

Christopher Nolan movies aren’t known for their emotional depth. His films – brilliant, bold, uniquely his own – are, for the most part, Swiss watches, finely-tuned machines where all the tiny, complex moving pieces coalesce into something seismic. They’re cerebral and fiendishly conceived, executed with astonishing craft and, in his later films, at a staggering scale. But they can be cold in the heart department – the revelations of Memento and Inception might involve loss, betrayals, and grief, but they unfold on a cerebral level, puzzle pieces that fall into place rather than genuine emotional blows.

Interstellar is Nolan at his most personal and intimate – a film about the love of fathers for their daughters.

Only one Christopher Nolan movie has ever made me cry. I remember it so clearly, sat in the IMAX at the Science Museum – the ideal place to take in a viewing of his extraterrestrial epic, Interstellar. As Matthew McConaughey’s Cooper returns to the Endurance spaceship after a botched mission on Miller’s Planet – a water-world where gravity-related complications mean that time moves considerably more slowly there than it does on Earth – he sits and catches up on 23 years of video messages from his son Tom and daughter Murphy. In a matter of hours (for him), he has missed their entire young life. Babies have been born, people have died. The brevity of the video clips only makes clearer all the time he doesn’t get to see in between. Only one message is from Murphy – she’s now the same age as him. And in the meantime she’s grown resentful – feeling angry and abandoned, resigned to the idea that her dad upped and left and probably isn’t coming back. Across the sequence, the camera zooms slowly in on McConaughey, sobbing, crumpling in on himself, breaking under the weight of it, the incalculable loss – of years, of relationships, of family. So many Nolan films play with notions of time. But none do so with the staggering impact of Interstellar, particularly that scene. In the darkness of the IMAX, my eyes became pools.

In the run-up to its release, Nolan’s expedition into the cosmos looked to be his most expansive, grand-scale film yet. And in many ways it was (and still is) – so much of the pre-movie hype revolved around Kip Thorne’s contributions to the film’s theoretical physics, the mind-bending science behind the wormholes, and adventurous notion of humans blasting off into the great unknown. In viewing, though, it feels like Nolan at his most personal and intimate – a film about the love of fathers for their daughters, and the lengths they’ll go to for them. Cooper’s mission to find a home for the future of humanity is really a mission to create a future for his daughter – one that will, ironically, rip him away from her, a sacrifice taken in order to be a provider. The film’s production title was even ‘Flora’s Letter’, named for Nolan’s own little girl.

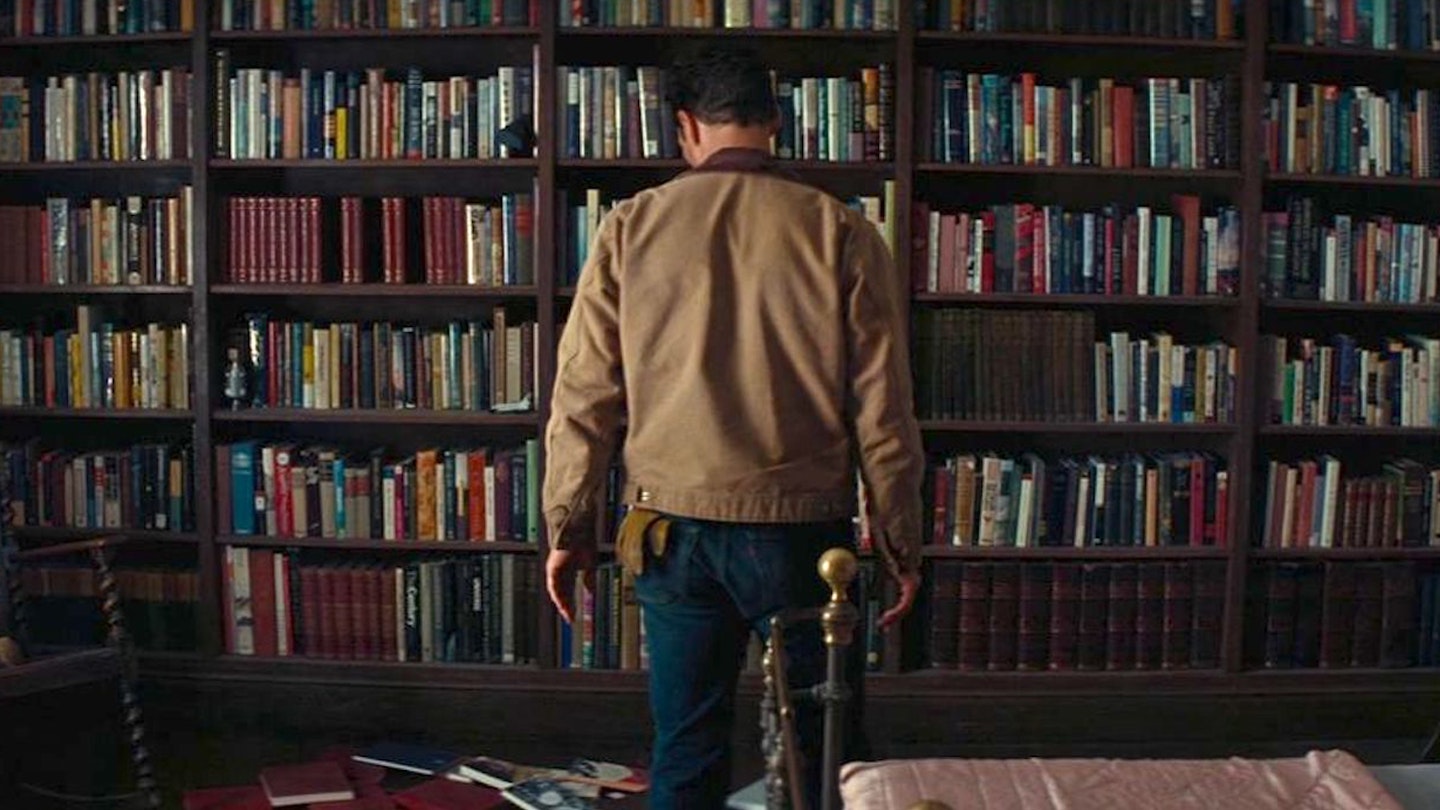

If there’s a point where people tend to baulk at Interstellar (which is perhaps Nolan’s most polarising film – it came in at a relatively-low #7 in the official Empire ranking) it’s the moment in the third act where Cooper finally voyages into the Gargantua black hole. There he enters the ‘Tesseract’ – a construct of four-dimensional space in which linear time can be traversed in neat rows. It’s here that the film becomes a true time-bending Nolan work – after soaring across the infinite void of space and venturing into a crushing vortex of gravity, Cooper is suddenly… home. Or, at least looking at home – trapped in the walls, watching the life (and the girl) he was forced to leave behind. Tracing the timeline of Murphy’s childhood bedroom, he transmits messages to her by nudging the books on her shelf and flickering the second hand of her watch. That idea – that love transcends time and space, that the connection between Cooper and his daughter can be the salvation of humanity – might be cheesy, or seem far-fetched, but it’s rather beautiful too.

In many ways, the sentimentality seems distinctly un-Nolan – those that dislike the Tesseract sequence in Interstellar might argue that the film goes from hard science-fiction to gooey emotional fantasy in one fell swoop, perhaps a remnant of the fact that Spielberg was once attached to the project. But on second inspection, it might be the most revealing thing Nolan’s ever done: it makes total sense that the man behind Inception and Memento can only explain the deep binding power of love amid an exploration of the far-reaches of space and multidimensional future civilisations. Only he would envision the father-daughter bond as a scientific phenomenon, something both bafflingly incomprehensible and yet completely rational within the laws of physics. “My connection with Murph, it is quantifiable,” says Cooper in the Tesseract. “It’s the key.”

It is the key, to Interstellar at least. There’s plenty to love about Nolan’s space movie – the 2001-esque feel of the intergalactic exploration, the fascinating vision of a Dust Bowl-inspired future Earth, the stunning imagery of light warping around the edge of a black hole. But its greatest joy is that it’s a glorious contradiction – Christopher Nolan’s most impossibly vast and most delicately intimate film, one that has all the brains you’d expect from him, but with a big, beautiful beating heart too. Don’t get me wrong – Inception is great, and I can see why it topped Empire’s ranking of the greatest Nolan films. But if I had to choose, you can keep your ice fortress. It’s the transdimensional bookcase of love for me.

READ MORE: Interstellar: How Christopher Nolan's Space Movie Achieved Lift-Off

READ MORE: Inception: Making Christopher Nolan's Psychological Action Epic

READ MORE: The Dark Knight Trilogy: The Complete Making Of Nolan's Batman Films