Here at Empire, we have a tradition of sharing one article from our year at Christmas — consider it a digital stocking-filler. As 2023 rolls out, let us bring you some bonus cheer with a feature that’s close to our hearts: our visit to the Portland headquarters of stop-motion animation legends Laika. We got up close and personal with the puppets, sat down for a lengthy chat with studio boss Travis Knight, and even got an extended set visit for Laika’s next big-screen epic, Wildwood. That won’t be out until 2025 (stop-motion takes time), so in the meantime, please enjoy the next best thing…

The dogfight was going to look awesome. The boy was sure of it. Buzzing from the movies he had sat through, enthralled, on Saturday-morning TV or at cinema matinées in his farm town outside of Portland, Oregon — stop-motion classics such as the Ray Harryhausen-enhanced The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad and Rankin/Bass’ Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer — he had already attempted to inject life into Star Wars action figures. Now, it was time for something a little more spectacular. He marched to his X-wing toy, like a titchy Wedge Antilles, grasped it in his eager hands and proceeded to film it, frame by frame, soaring through the sky, little explosions created using balls of cotton. His mind boggled at how incredible it was going to look when he unveiled his final cut.

“Well, it looked like garbage,” laughs Travis Knight now. “I was like, ‘I’m going to have this amazing aerial battle here!’ It was so fun to imagine what it could be. And then you see the end result, and it wasn’t what you imagined. So that was heartbreaking.”

Flash-forward some 40-odd years, and Knight is still tinkering with his toys. He’s still just outside Portland, Oregon. Except now those toys are no longer purchased from the nearest Walmart. And rather than his parents’ basement, all alone, he’s in a giant warehouse complex, assisted by roughly 400 ridiculously talented people. This is Laika, the studio behind the likes of Coraline, ParaNorman and Kubo And The Two Strings: 964 miles up the coast from Hollywood but light years away in terms of how things are done. No sequels. No chatter about “IP”. Productions that are not rushed through the system like fast-food, but baked like gourmet dishes in a clay oven. Their new stop-motion epic, Wildwood, has been in development for 12 years; it’s finally due out in 2025.

It’s not always been smooth sailing here, but this is still a place where dreams come true. Very, very slowly.

“I have a big aerial dogfight scene in this movie, with a giant bird,” smiles Knight. “So, you know, good things come to pass.”

———

There’s a go-kart track around the corner from Laika, called K1 Speed. Every now and again, somebody from the studio will head there, clamber inside a buggy and hit the throttle, hard. Whizzing around a circuit at high velocity is a form of recalibration. Because at Laika, despite the presence of an in-studio coffee shop called Dripster’s (named after a location in Wildwood), things move at, well, puppet pace.

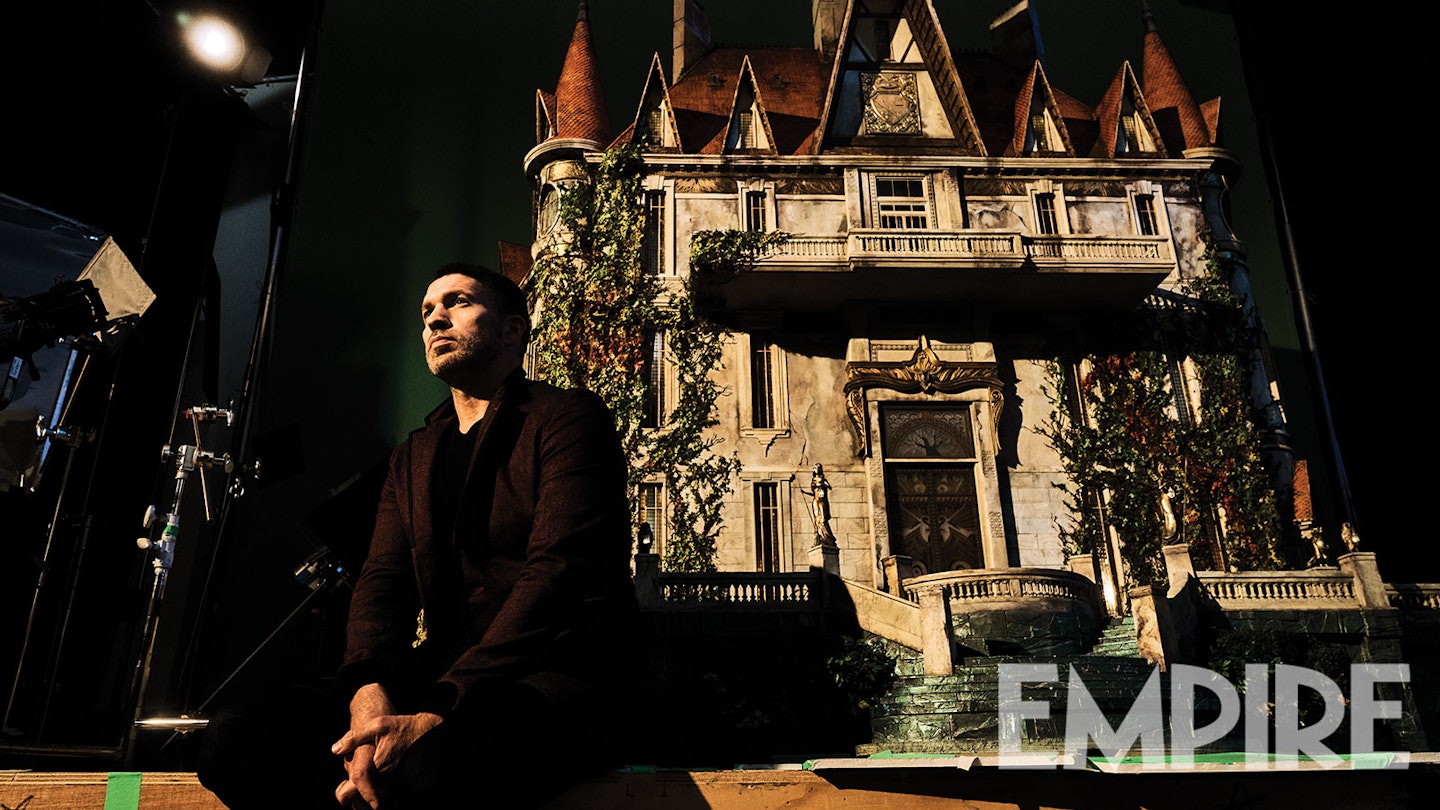

When Empire visits the studio in early April, it proves to be the quietest set visit, by far, that we’ve ever experienced. The usual sounds of a busy shoot — walkie-talkies, clapperboards, Michael Bay yelling at a grip — are absent. In fact, it’s hard to detect any activity at all. But as we stroll around the hushed, 400,000-square-foot warehouse complex, we find incredible things happening behind curtains. A massive eagle, wings outspread. A study, complete with marble fireplace and grand piano, the dwelling of an oversized owl. Forest tableaux with tangled trees and creeping ivy. All in miniature, and precisely put together by hand or using nifty tech: even the tiny leaves for the foliage have been laser-cut.

And rather than a bustling crew gathered around the camera on each micro-set, there’s just a single, hyper-focused person. “Until we shout action, you’ll have set dressers, cameramen, motion control, lighting, gaffer and somebody from Puppets doing final checks,” says Laika’s Dan Pascall. “But as soon as we get launched, everyone’s out and then the animator’s in there. I mean, for a 20- or 30-second shot they can be in here for months on their own. It’s a pretty solitary thing.”

Wildwood is a fantasy epic directed by Knight, based on a book by Colin Meloy, frontman of the band The Decemberists. It’s a sprawling tale that’s actually set in and around Portland, in which a young woman, Prue McKeel, finds herself in an enchanted forest world. On the day of Empire’s visit, there are 25 animators working on the project. But those animators are hidden away and silent, like monks in prayer, rapt in focus over the tiniest of details. When we encounter Jason Stalman, who’s worked on Laika productions since 2012’s ParaNorman, he’s attending to a throne room the size of Prince George, concentrating on the puppet of a female character who is reacting to something in the scene.

“She’s doing very little, but you have to keep the character alive,” he explains. “She’s trying to be alluring, so she’s doing all these little movements and body adjustments, which is really hard to do.” Another challenge is her dress, which has to move independently too. The solution: tiny foam pads beneath the dress, to which the fabric can be pinned to, creating — eventually — the illusion of a swishing, real-looking costume.

Creating a performance frame by frame requires an enormous amount of mental energy. “It’s strange; it takes you a minute to come back to the normal world after you’ve done a day of this,” admits Stalman. “People could think, ‘How the hell do you do it? It’s so boring.’ But I like it, because the world is so crazy and fast. This feels nice, to do this little, delicate thing.”

One animator at Laika is likely to, in a week, create approximately three-and-a-half seconds of screentime. That’s the kind of stat that might prompt some studio executives to kick over a watercooler in frustration. But Knight knows from experience that you can’t rushthesethings. Puppets move at their own tempo.

“You could take shortcuts,” he says. “But to me, the film requires whatever it requires. I do think making a movie like this is stupid. It’s the stupidest way to make the movie. It’s harder. There’s more pain. But I also think there’s more joy as well. I’m aware of the ticking of the clock and the mortal coil and everything else. I do want to tell as many stories as I can before my time is done. But when this group of people come together to create something, it’s the most satisfying thing I’ve ever been a part of.”

———

Back in 2009, stop-motion was on life-support (quite possibly hooked up to a tiny, hand-crafted IV). Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride had made its money back a few years earlier, but nobody in Hollywood was baying for more. And advances in CG animation had led to studios looking for the next Shrek, not the next The Nightmare Before Christmas. “Stop-motion has always been the red-headed stepchild of animation,” says Knight. “And CG could effectively do everything we could do in stop-motion, but better. There was certainly a moment where I think any of us who were practitioners of the craft were asking ourselves, ‘Is there a future here?’”

But he, and others, were deeply in love with both the process and vibe of stop-motion. Knight, whose father is Nike magnate Phil Knight (as played recently in Air by Ben Affleck), had abandoned plans for a career in finance, deciding to follow that passion, wherever it might lead him. And it led him (after a brief stint as rapper ‘Chilly Tee’) to Laika — formerly Will Vinton Studios, which Phil Knight acquired in 2002, Travis becoming CEO. Laika is the name of a dog sent into space by the Soviet Union in the 1950s; Knight’s career choice seemed as daunting an odyssey as that of the cosmic pooch.

Especially when the studio embarked on its first feature film, Coraline, directed by The Nightmare Before Christmas’ Henry Selick and on which Knight worked as lead animator. Not only were financiers reluctant to back a stop-motion animation, but they proved unenthusiastic about the lead character being female — and not a Disney princess, but a regular teenage girl. Despite it being based on a book by Neil Gaiman, despite Selick’s pedigree, despite the stunning visuals that Laika were orchestrating, the mood was grim. “There was a lot of anxiety,” remembers Knight. “When we were trying to find partners who understood what we were trying to do, we were getting nothing but rejection. It was like high school all over again.”

Then, at the premiere the weekend before it came out, a studio executive approached him. “According to the data it was going to bomb tremendously. And I remember an exec put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘I’m sorry. You gave it your best shot.’ In this moment where we’re trying to have this big celebration of what the crew had created, it was just tainted by this fact that it didn’t work, and we were going to fail.”

But it did work: after a surprisingly strong opening weekend, Coraline found legs, going on to make $125 million. “Fast-forward a couple of months from the premiere, and that same executive team was asking me to make ‘Coraline 2’,” Knight recalls. “I was like, ‘No, we’re not gonna make Coraline 2. We’re gonna tell a different story.’”

Laika were off and running. Their follow-up, 2012’s ParaNorman, was a zesty zombie comedy. 2014’s The Boxtrolls was a raucous romp featuring mischievous creatures and industrial quantities of cheese. 2016’s Kubo And The Two Strings, Knight’s directorial debut, was an elegiac stop-motion samurai epic. And 2019’s Missing Link was a massively fun riff on Around The World In 80 Days, with a male Sasquatch named Susan. The studio’s fare has remained artisanal, original and eccentric. And while the box-office figures have not been astronomical, those who do see their films tend to treasure them. In fact, some viewers became so inspired that they’ve ended up as employees at Laika themselves.

“There are people who saw ParaNorman who work here now,” says the studio’s head of production, Arianne Sutner. “Same thing with Coraline. You know, we don’t make tons and tons of stuff, but what we have has a special impact. People love it for all of its unusualness.”

———

In Laika’s ‘Story Room’, where Empire meets Knight, bookshelves teem with thick volumes: subjects include P.T. Barnum, Art Deco, Cape Cod houses and fashions of the Victorian age. In a cabinet, meanwhile, are DVDs, many of which seem like unusual references for an animated adventure: the documentary Fires Of Kuwait, The Lord Of The Rings, The Birds, Michael Clayton, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster.

“The Grandmaster is a beautiful film,” Knight enthuses. “That was a huge inspiration when I was working on Kubo, because of how gorgeously it was shot. Michael Clayton is more to do with lighting and composition, that sort of thing. But yeah, we pluck inspiration from a variety of sources.”

The stop-motion process is intrinsically difficult and time-consuming: boxes of replacement faces (each bearing a unique code) are trolleyed to set to create every smile, smirk and splutter. Nine 3D printers work overtime to make moulds of characters, which are then dressed with bespoke costumes, fitted with wigs and prepared for their moment in the spotlight. The quantities required are mind-boggling: Missing Link called for 106,000 unique faces; Wildwood will have far more, while also boasting 120 sets, double the number built for Kubo.

But Laika is determined to keep crashing through the technical obstacles encountered, in a quest to become ever more cinematic. For Kubo, the studio tackled water, a giant skeleton and origami animation. For Wildwood, Knight is thinking bigger. He has the benefit of being fresh off his first live-action venture as director, 2018’s Bumblebee, the best film in the Transformers franchise to date. And he’s brought on cinematographer Caleb Deschanel, veteran of such non-puppety epics as The Right Stuff and The Patriot. With the rest of the team, they’re making innovations both large and small. They’ve cracked a way to put muscles into puppets’ arms (“We’ve never done that before,” says Knight. “It looks amazing when I see it on-screen”) and to create a fully articulated rat puppet so minuscule that it can rest on your pinkie (“The joints are so small — if you drop it, it looks like a human hair”). Most dauntingly, they are orchestrating a vast battle sequence, which could make Jason And The Argonauts’ skeleton brawl look like a pub barney. “It’s the single most difficult thing we’re tackling on this movie,” says Knight. “We’re starting to chip away and tentatively stepping into, like, ‘Oh God, oh God, oh God, how are we gonna do this?’ But I think it’s going to work. And you’ll tell me when the film’s all done if it did. Stop-motion films tend to look like they’re shot on a table-top, because they are. Moving a physical object a frame at a time and trying to give it life, that’s its own challenge. And then you bring all the kineticism you would have in a live-action action movie... It’s so hard.”

Spectacle is one thing. But Laika’s filmmakers are equally focused on their characters. Hailed for their progressiveness and inclusivity, they have brought the world Coraline Jones, a female animated hero like no other. ParaNorman’s Mitch (voiced by Casey Affleck) was mainstream cinema’s first openly gay animated character, leading to Laika being nominated for a GLAAD award. And they’re determined for Wildwood’s characters, including Prue, another young female hero, to connect powerfully with viewers.

To create nuanced puppet performances, Laika animators study live-action ones. “There’s a moment in Dangerous Liaisons with Glenn Close on a sofa, and John Malkovich is asking her, ‘What’s your story?’” says Jason Stalman of a touchstone for the scene he’s animating today. “The way she delivers her lines — I’m getting the shivers — I reacted so much to that that I thought if I could even get one tiny piece of stardust from that and put it into this, I’m going to try. It’s nice to show a thought process happening in a two-inch piece of plastic head.”

The animators also study themselves. Study their colleagues. And even study their own families.

“The design of the little baby in Wildwood is actually based on my nine-year-old son. That’s how long we’ve been developing this damn thing,” reveals Knight. “But he’s voiced by my two-year-old son. It’s a really strange thing to hear that little guy’s voice come out of my older guy’s puppet body. There’s a scene in the film that’s incredibly intense and the baby’s screaming and crying and people go, ‘Oh my God, how did you get that baby to do that?’ I’m like, ‘Well, I changed his diaper.’”

———

2023 makes the 125th anniversary of the very first stop-motion film ever created: 1898’s The Humpty Dumpty Circus, in which dolls of circus acrobats, elephants and donkeys came to life. That historical artifact has been lost forever, but the artform itself has refused to follow suit. Last year saw Guillermo del Toro venture into stop-motion with Pinocchio and Henry Selick return with Wendell & Wild. Aardman recently teamed up with Lucasfilm for a stop-motion Star Wars: Visions short (like Travis Knight’s childhood film, it features an X-wing, plus actual Wedge Antilles), while a Chicken Run sequel is clucking its way to Netflix.

Much of the credit for the re-animation of stop-motion must go to Laika. They’ve kept on ploughing forward, dedicated to the medium. The studio is expanding and transforming, with Laika set to move into the live-action realm. The first of those projects will be Seventeen, based on a John Brownlow book about the world’s most lethal hitman. “It’s a thriller with soul,” says Knight. “Whatever we’re developing, be it animation or live-action, it’s going to be something that’s emotionally resonant, that blends darkness and light and humour and heart.” But at the core of the studio, despite the fact they’ve incorporated elements of CG into their films since the start, will remain those patience-testing puppets.

While Wildwood is their biggest, most ambitious project yet, they’re rolling other dice even before that’s out. Including The Night Gardener, a stop-motion movie based on a script by Bill Dubuque, creator of Ozark, and described as a “neo-noir folk tale”, which is Laika’s first that’s not for kids. “This film is not a family film, at all,” Knight says. “There’s never been a film made like this in our medium. And that really excites me. It’s a beautiful story, it scares me, and it’s going to be an extraordinary piece of cinema, I think. Or at least has the potential to be.”

The Laika philosophy is an admirable one: keep pushing in new directions, never repeat yourself. But one thing remains consistent for these pioneers in the drizzly Pacific Northwest. The pain of making one of these damn films, and the pleasure of — finally — watching the results.

“You know, these things are like little vampires,” Knight reflects of the puppets that fill his warehouse. “They suck the life out of the people that touch them. At times, it’s really frustrating — they won’t do what you want them to do. But when I see a puppet that’s been imbued with life, because an animator on a stage has had an emotional connection with an inanimate thing, an assemblage of silicon and steel... Well, it’s the closest thing to magic I’ve ever witnessed.”

Wildwood is in cinemas in 2025.

Photography by Shayan Asgharnia, shot exclusively for Empire at Laika Studios in Portland, Oregon, on 4 April 2023.