This article first appeared in issue 227 of Empire magazine. Subscribe to Empire today{

Illustrators often embrace a specific personal viewpoint, an idiosyncratic direction which sets them apart from the competition and, at times, even defines their style. My approach demands at least three elements in evidence before any work leaves the drawing board: a certain sense of visual magic, a heightened aura of tension, and a larger-than-life quality that characterizes the subjects in most of my paintings.

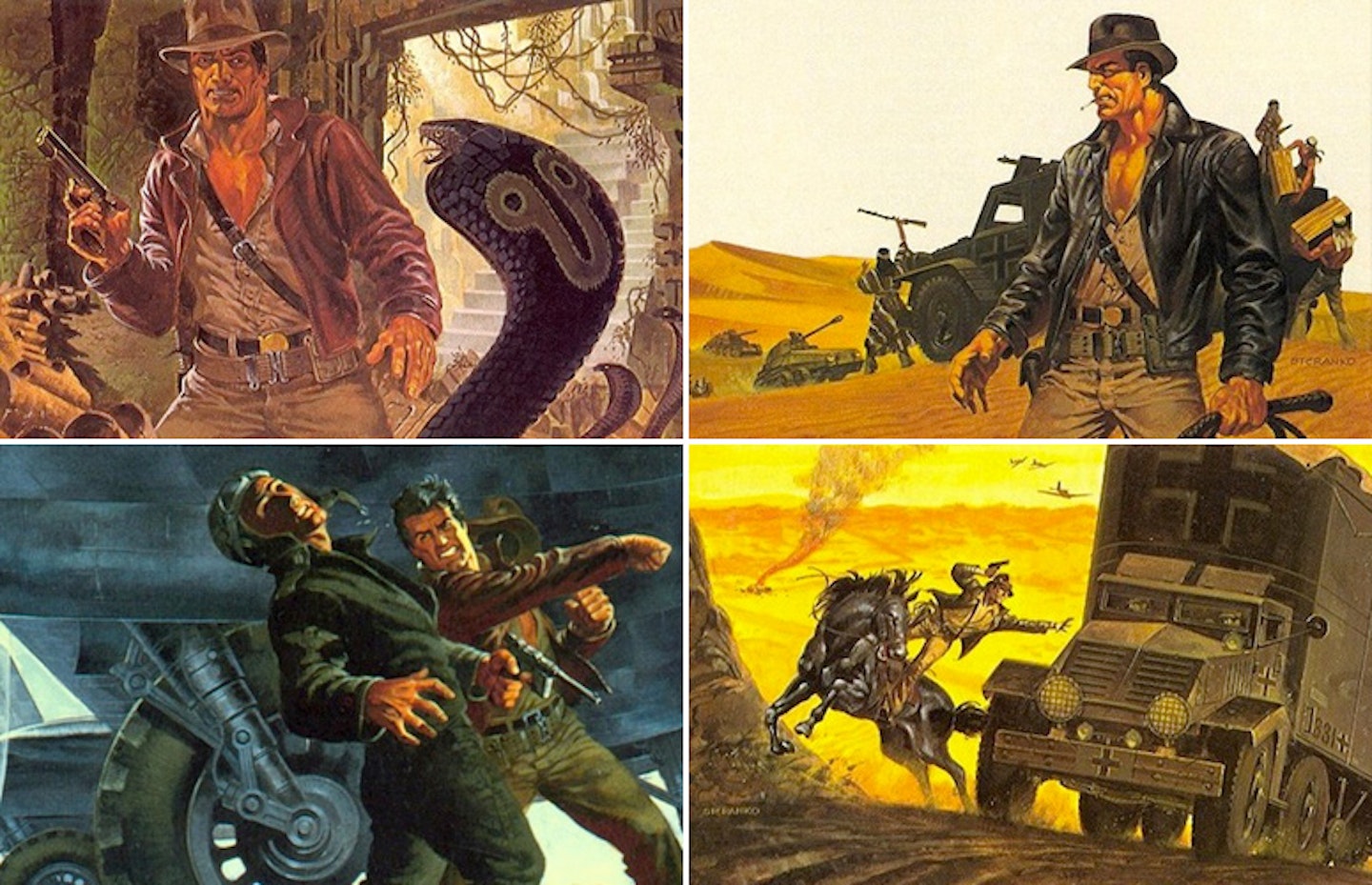

I believe it was primarily the latter which prompted George Lucas to assign me the initial production illustrations for Raiders. He was already familiar with my book cover art and Marvel comics work (in addition to me media coverage of Star Wars), but it was a series of drawings I’d visualized for Conan creator Robert E. Howard’s two-fisted soldier of fortune Francis Xavier Gordon – aka El Borak – that nailed the assignment. George found the hard-edged attitude and dangerous ambience of the images to be exactly what he wanted for his adventure hero – who just happened to be named after his dog, Indiana! That alone sold me on the project.

Of course, the fact that the film was slated to be directed by Steven Spielberg and produced by George Lucas didn’t hurt, either. They knew how to make movies, movies that made cinematic history, and history that changed the landscape of popular culture. So, when I was requested to do for Raiders what my friend Ralph McQuarrie had done for Star Wars, I plugged it, without hesitation, into my schedule. I prefer film work when I’m asked to contribute from point A, before anything has really been cast in stone, a point where I can allow my imagination to roam without restraint. It’s the most fun and, ultimately, the most satisfying. The assignment fulfilled that imperative perfectly.

George was tapping into several lost areas – the genre which spotlighted the kind of globetrotting he-man who energized the such vintage films such as Too Hot To Handle, China Seas, and The General Died At Dawn; the Saturday-afternoon serials with their spine-cracking cliffhanger endings; and the lightning-paced adventure pulps of the 1930s – to create a new character, like Buster Crabbe, Kane Richmond, and Clayton Moore rolled into one, a character that might be best described as an incarnation of Doc Savage out of Humphrey Bogart. I was well versed in all three areas and had probably set a Guinness record for visualizing major heroes in print, including James Bond, The Shadow, Sherlock Holmes, Spider-Man, The Phantom, Mike Hammers, Buck Rogers, Batman, Captain America, Sam Spade, The X-Men, Kirk and Spock, the Green Hornet, Conan, Luke Skywalker and many others.

"The primary element is his face and expression: tough, rugged, weathered by a thousand perils." Steranko

"The primary element is his face and expression: tough, rugged, weathered by a thousand perils." Steranko

Lawrence Kasdan generated a script or two from a Lucas outline in 1978. It was from that source that George selected a number of key scenes to be illustrated, with, as I understood it, a two-fold purpose; as a graphic presentation to sell the project to a studio and to establish the look of the film, its characters, settings, and elements.Steven and I had dinner one night in Burbank while he was in the process of cutting 1941 and we spoke extensively about Raiders’ visual quality. He cited numerous foreign films, all with a dark and ominous ambience, suggesting considerably more noir that the traditional adventure films. However, when creating the Indy paintings, I maintained what I felt was the classic Spielberg approach: compelling and often dynamic imagery that always serves the storyline.

Lawrence Kasdan generated a script or two from a Lucas outline in 1978. It was from that source that George selected a number of key scenes to be illustrated, with, as I understood it, a two-fold purpose; as a graphic presentation to sell the project to a studio and to establish the look of the film, its characters, settings, and elements.Steven and I had dinner one night in Burbank while he was in the process of cutting 1941 and we spoke extensively about Raiders’ visual quality. He cited numerous foreign films, all with a dark and ominous ambience, suggesting considerably more noir that the traditional adventure films. However, when creating the Indy paintings, I maintained what I felt was the classic Spielberg approach: compelling and often dynamic imagery that always serves the storyline.

Clean, powerful narrative is the force we both serve and I pursued that direction aggressively, in addition to understanding the director’s predilection for peppering his dramatic scenes with light, sometime humorous moments. The result was a series of productions illustrations rendered with a narrow, low-key palate (rather than more colour and chroma, which is often evident in my work). Additionally, I adapted Steven’s preference for the denser atmosphere he discussed by using massive, shadowy shapes in each rendering. (He ultimately aborted the dark-vision approach before production began and for straight ahead Spielberg).

In suggesting scenes he wanted visualized, George offered only the most minimal detail. So, I began with the image of Indy in the desert because it offered the best showcase to reveal his demeanour, clothing and props. He would sport a bomber jacket (like George wears), a beat-up fedora (not unlike Fred C. Dobb in Treasure OF Sierra Madre), and carry a whip (similar to the hero of Zorro’s Fighting Legion). I added the Sam Browne belt (military strap over the right shoulder), the WW1 garrison belt for the holster, and the khaki shirt and slacks. By positioning Indy close to the viewer, he became the dominant factor in the shot – which I underscored by graphically cropping him at the top and bottom edges of the Cinemascope-proportioned frame.

The hero’s action-orientated persona is supported by his ready-for-anything stance, legs apart like a street-fighter maintaining balance; he’s just as prepared to the whip (which George suggested) as he is the opposite hand, which flexes for action. The primary element is his face and expression: tough, rugged, weathered by a thousand perils – a leitmotif equally shared in serials, comics and cinema. As I applied the final brushstrokes, Indiana Jones lived! (Later, Tom Selleck was cast in the part, but when his Magnum P.I. schedule was prohibitive, Harrison Ford replaced him. I still remember getting a call from George’s Girl Friday Carol Titelman after the first rushed were screened at the Lucasfilm offices and hearing her exclaiming, “how close Harrison Ford resembled the figures in the painting!”)

The subsequent illustrations depicted other sequences from the story, all showcasing Indy in his bare-knuckle best. Soon afterward, George and Steven pitched the project to Paramount Pictures – and the rest is film history. I’ve often been asked if I had any idea how successful the movie would be around the world. My answer is simple: it never occurred to me that it would be anything but a mega-blockbuster because it was the brainchild of two mega-talents, two of the most visionary and skilled filmmakers in the entertainment universe. Their hearts were beating with one rhythm as they breathed life into a character moulded from a cold, bloodless genre and transformed him into cinematic icon as popular and compelling as any that ever ignited the silver screen.

Head back to our Indy hub for more exclusive features and interviews celebrating all four Indiana Jones movies.

![] Empire Magazine

![] Empire Magazine

For the best movie coverage every month, make sure you subscribe to Empire magazine - also available to download on iPad.