This feature was first published in the July, 2009 edition of Empire Magazine

There can be only one. Followed by a sequel. And three more sequels, two TV series, a Saturday morning cartoon, an anime and a ton of merchandise. Highlander wouldn't die. The self-contained film that cast a Frenchman as a Scot, a Scot as a Spanish Egyptian and seemed to leave no scope for even a single follow-up, somehow launched a franchise that has endured for thirty years.

Its huge ambitions were often laid low by mundane practicalities, but it weathered all due jointly to good luck and the tenacity of its independent producer owners. The ultimate high concept – sword-fighting immortals battling throughout human history – it has lumbered through its incarnations with no internal continuity, and the results have more often than not been vilified by Highlander’s own fans, let alone the viewing public at large. And yet that fan-base still exists, attending conventions, writing (usually filthy) online fiction and continuing to return to the well in the face of variable quality. "After each awful sequel I promise myself I’ll stop caring," wails one online movie blogger: "Has any franchise ever hated its fans more than this one?"

The unwieldy saga began modestly enough. Greg Widen wrote his original script as his senior thesis while studying film at UCLA, and it eventually found its way to Bill Panzer and Peter S. Davis; producers who had not long since marshaled Sam Peckinpah’s final film The Osterman Weekend. "The script itself was rough," recalls Davis, "but we were captivated by the idea." After a second draft from Widen, Peter Bellwood and Larry Ferguson, veteran scriptwriters who had worked with Davis-Panzer before, were brought in to rewrite the screenplay.

Most of the key elements are already present in Widen’s script: the idea of the "game" of immortals fighting each other until only one remains; the characters of Connor MacLeod and Ramirez; the beginnings in the medieval Scottish highlands and the police investigations in present-day New York; decapitation as the only way to kill an immortal; flashbacks to MacLeod’s previous "lives".

But Widen’s vision is much darker than the one that eventually made it to the screen, inspired to a large extent by Ridley Scott’s The Duellists (itself based on a Joseph Conrad short story and heavily influenced by Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon) and interested primarily in the bleak concept of an apparently meaningless recurring battle, fought over centuries between MacLeod and an unnamed Knight. Ramirez at one point describes immortals as "nothing more than walking corpses living only to slaughter each other in an insane quest."

Bellwood and Ferguson’s version lightens the tone considerably, and nails down the concepts that would continue throughout the series: the "Quickening" transfers of immortal power, and the idea that immortals can’t have children (Widen’s MacLeod has fathered "thirty-eight children to nine wives, and buried them all"). The unnamed Knight becomes flamboyant cackling psycho The Kurgen (Elm Street mania wasn’t quite at its height by 1986, but it can’t be coincidence that The Kurgen signs his hotel register with the assumed name "Krueger"); and Rachel and Heather, respectively MacLeod’s adopted war orphan and medieval Scottish bride, are added for emotional value. "We were very pleased with the finished script," recalls Davis. "We presented it to EMI and to Fox for a combination funding, and off we went!"

Enter Russell Mulcahy, an Australian director hired by Davis-Panzer due to their fondness for his 1984 killer-pig horror cheapie Razorback, but better known at the time in the UK for the urban legend that he nearly drowned Simon Le Bon while filming Duran Duran’s Wild Boys video{

"His agent assured us he’d be fine, but he could barely say 'Hello, my name is Christopher,'" recalls Davis. A language coach was constantly on set, and six weeks of post-production were spent looping every line of Lambert’s dialogue. According to Mulcahy though, the Scots cast members turned a deaf ear to their clan leader’s Gallic tones: "They didn’t care. It was a really tight bunch of people just enjoying the movie. It was freezing cold, and they’re in kilts in the mud, drinking whiskey first thing in the morning. They were mad and wonderful."

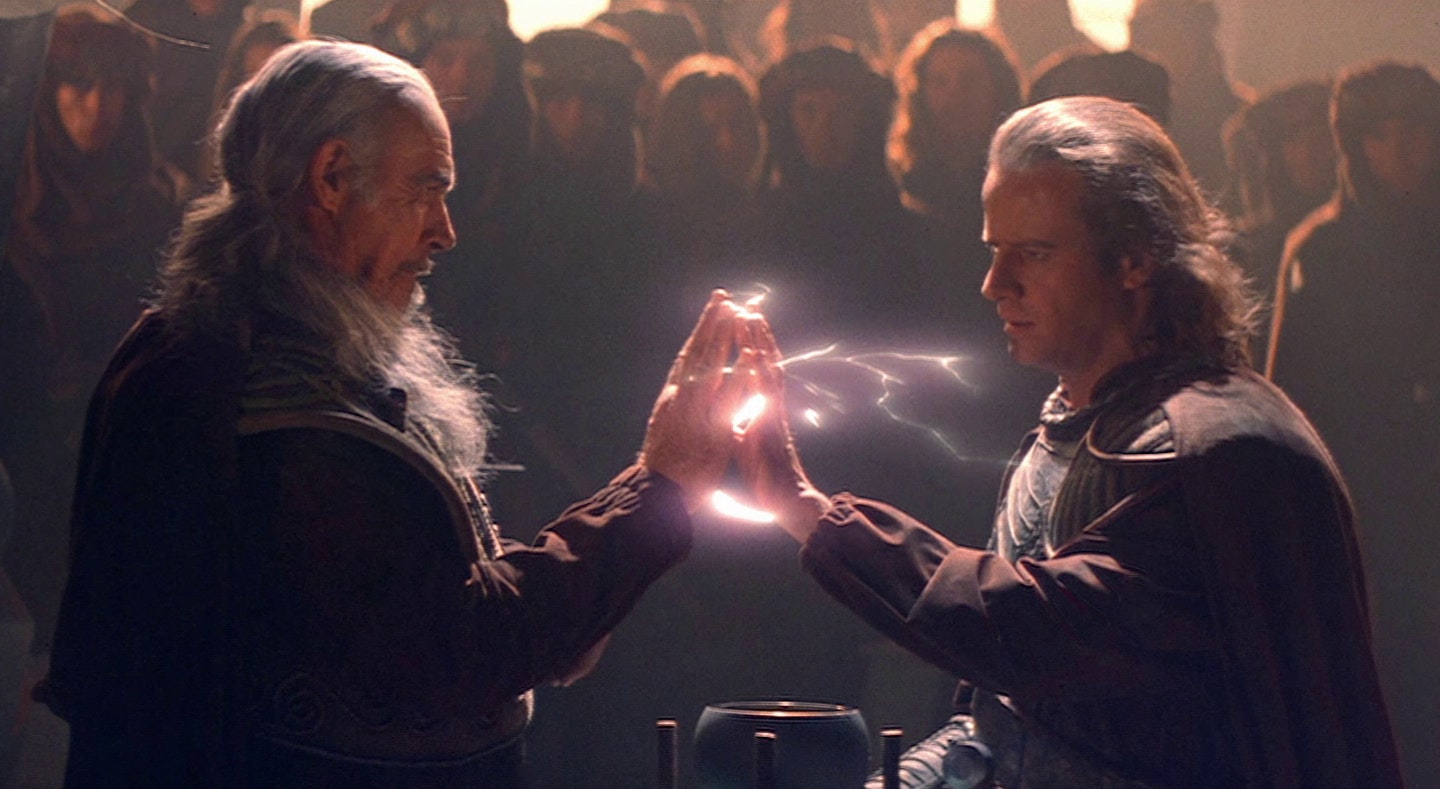

Sean Connery’s casting as the Scots-accented Egyptian Juan Sánchez Villa-Lobos Ramírez, "chief metallurgist to King Charles V of Spain" was an equally weird success, and a thrill for Mulcahy, who found himself directing an icon from his childhood. "He was huge and gracious, and very expensive! We only had him for seven days, and if we’d gone over schedule with him he would’ve got paid an extra million dollars. On the last hour of the last day he said to me, 'You’re not going to finish, are you?' And I said, 'Hang on,' and I got him to stand against a green, leafy background, and I was like 'Turn left, turn right, smile, swish your sword, do this, do that, turn around...' It came to the last minute, and I said, 'Cut! Wrap!' He said, 'You bastard.'"

Mulcahy’s quick-cutting MTV directorial style and mad transitions (like the fish tank that becomes a Scottish loch) raised a few eyebrows, and he recalls that old-school director of photography Gerry Fisher "nearly had a stroke" at some of the techniques he wanted to try out: "I told him to turn all the lights off and just shoot the flashing neon. He went, 'Oh my fuck!'" But his rushes were accepted, and the finished product was approved by everyone except Queen, who provided half a dozen songs for the soundtrack and insisted on endless remixes until they were satisfied.

It seemed a moderate hit was on the cards, but, initially at least, that was not to be the case. Contemporary reviewers were generally positive about the film’s intriguing concept but less impressed by its uneven tone - lurching between deadly serious and very camp - and its occasionally ropey effects, like the all-too-visible wires suspending Lambert at his climactic quickening. Plus, "Fox basically threw it away," says Davis. "They thought all the back-and-forth between different times was confusing, so we were forced to take some of the flashbacks out [the American theatrical cut loses the WWII scene that explains who Rachel is], and they didn’t support it with any type of serious promotion."

The American poster featured just a grainy black-and-white headshot of Lambert and no indication of the film’s content. Ironically though, it was the casting of Lambert that proved the film’s salvation. Highlander, on the back of Lambert’s Cesar award for his performance in Subway, was the second highest grossing film of the year in France. Word-of-mouth spread throughout Europe, and Highlander’s reputation began to grow, leading inexorably to the ordeal of Highlander 2: The Quickening.

Conceptually flawed, poorly planned and cursed with bad luck, the 1991 sequel was doomed from the beginning. "It was quite a struggle," says Davis. "Every morning I woke up and realised that the best part of the day was behind me." According to Mulcahy, "It was a dumb idea, shot in the wrong place."

That place was Argentina, in the middle of a catastrophic financial crisis. During the late eighties and early nineties, the Argentine government’s fiscal policy of gigantic borrowing coupled with the creation of more money led to inflation so rampant that it all but led to the disappearance of the currency. Not good news for a production team lured there on the promise of reduced production costs by the Argentine producer Alejandro Sessa.

Sessa, a close friend of Davis', had been involved in low-budget filmmaking in Argentina since the early eighties – producing and directing cheerfully salacious fantasy quickies like Amazons, Barbarian Queen, and The Warrior And The Sorceress - and was confident that the South American country’s filmmaking infrastructure could cope with a multimillion dollar American sci-fi blockbuster. "He was a wonderful man," recalls Davis, "but it quickly became clear that, while they could take on films like Two To Tango, this was very much more demanding from a technical point of view, an action point of view, in terms of the production design, the type of gear that was required, the type of personnel that was required... They couldn’t handle it."

Extra personnel were flown in from the UK and Los Angeles and housed in hotels, which added a fortune to the budget and caused problems with the Argentine unions, not to mention tension between the Argentine and British crews, for whom the Falklands war was still in relatively recent memory. "Friendly" lunchtime food fights were eventually banned when bottles started being thrown instead of bread rolls. The bonding company was hovering – according to Davis "sure that Bill Panzer and I had managed to siphon off five million dollars and put it in Uruguay, even though they controlled the chequebook" – and fretting over the spiraling costs of the gargantuan sets.

The long street on which the opening set-piece takes place was entirely built for the film and included a working railway system. It also had to be ready in time for the arrival of Sean Connery, on an incredibly tight six-day schedule for which he was paid $3m. A scratched negative of a crane-shot of Connery caused, at the star’s insistence, an expensive weekend re-shoot. "It was character building," says Davis now. "I even eventually forgave Alejandro."

"It was fucked up and strange and ridiculous," is the assessment of Mulcahy, who in the intervening five years had returned to videos and been fired from Rambo 3. "Christ almighty, what a disaster." And this is before any mention of the actual script. "It was nearly impossible to pull off, I thought," says the director, "and then when I did read it, it was trying to undo the myth."

Perhaps the most sensible thing about the original film was its refusal to speculate on where the immortals have come from. With the seemingly intractable problem of there being no immortals left however, Connor MacLeod having won the "prize" of mortality, fertility and omniscience at the climax of Highlander, the decision was made: they’re from space!

Nobody is willing to take credit for this. "I don’t want to speak badly of the deceased, but I think it was Bill’s idea," chuckles Davis (Panzer was tragically killed in a sporting accident in 2007). Apparently MacLeod was not born in Glencoe after all, but had been exiled to Earth from the planet Zeist with his memory wiped after a failed coup against the tyrannical General Katana. By 2024 MacLeod is aged and frail, but his prize is undone and his youth restored with the arrival, for reasons best known to themselves, of Katana and his henchmen. There follows some business about terrorists dismantling a synthetic Ozone Layer run by the corrupt Shield Corporation of which Katana has latterly joined the board of directors. And yes, Ramirez, despite his decapitation in 1541, returns when MacLeod suddenly remembers that all he has to do is call his name. Or something.

"I thought the Planet Zeist stuff was completely stupid – it was such a cop-out," says Mulcahy. "For some reason I agreed to do it, and then I tried to get out of it, and they tried to sue me. It was on the front page of Variety!" [Mulcahy’s memory seems to be faulty here: the Variety story reports Davis-Panzer attempting to sue Mulcahy for $9m when he allegedly reneged on a verbal agreement to direct Highlander 3].

"I don’t really blame the writers," he continues. "It’s just that the whole script was never completely filmed because of the financial problems. A lot of the ideas and stories were never shot, so the film is a bit of a patchwork. The bond company shut us down and brought in a butcher editor, and the film that was released just wasn’t finished. The first one I’m very proud of, but the second one I’m not, although it’s got some good moments."

Those moments include the street sequence, enormous even by today’s standards and perhaps the last real hurrah of pre-CGI effects, as Lambert mounts a hover-skateboard to battle flying Zeist hitmen, and triggers a massively pyrotechnic double-quickening that destroys the entire set. There’s also a great scene where Lambert and Connery are shot to pieces at a military checkpoint, reviving later in hospital with Connery complaining about the holes in his waistcoat. And there’s certainly strong evidence that the publicity blitz on its release, regardless of negative reviews, poor fan reaction, and multiple cuts across different territories, further benefited the first movie, with video rentals rising sharply as audiences who had missed it thus far sought to catch up.

Highlander 2 though, remains a train wreck, despite subsequent tweaking. Many films have re-shoots, but few can boast them four years after their original release. The so-called Renegade Version, released on DVD in the US in 1997, contained a newly filmed mountainside truck chase deemed essential to the story but not previously completed, alongside various other rearranged and expanded scenes. The new cut also acknowledged the howls of derision from the original’s fanbase by deftly removing all mention of Zeist, re-editing and dubbing to posit that the immortals are from a distant past on Earth, technologically advanced enough to have developed time travel.

It’s hard to see quite how this is an improvement (if anything, it makes less sense than Zeist), but this version is now regarded as definitive, if not canon. Subsequent Highlander, in all incarnations, ignores it, but Peter S. Davis insists that "as a separate piece of work, I think it’s quite wonderful. It’s a very good-looking film, and of all the sequels, I like it the best." American fans got a further re-release of the Zeist-less version in 2004, this time as simply Highlander 2 (no subtitle), with new special effects. Mulcahy claims never to have had any involvement with any version other than the original.

In any incarnation, an experience like Highlander 2 would have derailed a weaker franchise, but more sequels followed. In the absence of Mulcahy, Davis-Panzer hired another music video director, Andy Morahan, for Highlander 3 in 1994: released in the UK as The Sorcerer, in Sweden as The Magician, in the rest of Europe as The Final Conflict, and in the US and Canada as The Final Dimension. The latter title is the correct one according to Morahan, "even though it wasn’t the final anything."

Ditching Zeist (or whatever), the film posits that Connor MacLeod never really won the prize at the end of the first Highlander, because another forgotten immortal had been stuck in a cave for four hundred years. Morahan had worked extensively with Guns N’ Roses, not least on the infamously overblown November Rain clip, and for a while it seemed that he had secured the coup of Axl Rose and co. providing the soundtrack. "They loved that Queen had done the music on the first one and I had Axl ready to go," says Morahan. But Rose suddenly revealed an unexplained dislike of Mario Van Peebles (on hand as cartoony main villain Kane) and refused to provide any songs if the actor remained in the film. "So that screwed that one," says Morahan. "Miramax wouldn’t get rid of Mario. At the time I thought it was more important to have Guns N’ Roses!"

Of all the sequels, The Final Dimension hangs together most successfully as a standalone movie, but feels like a retread of the original, to the extent of Kane repeating the set-piece where The Kurgen drives a car with a screaming passenger into headlong traffic. Morahan views it as a qualified success. "At that stage Lambert genuinely wanted to do another one, there’s a lot of music in it, Mario, Chris and Deborah [Unger] were good, and I got some big, cool montage sequences in, so there were bits that I thought worked well. But all I wanted to do really, after the debacle of the second one, was remake the first."

Shooting was at least finished this time, but a bond company was still involved in getting a finished product to the screen after some "irregularities" on the production side. "Davis-Panzer were kind of at arm’s length on this one," recalls Morahan, "but the French producer Claude Leger was, shall we say, 'difficult', and I ended up finishing the film with no support from anybody. I was just left to crash and burn, basically."

"It was a French/Canadian co-production, and under the terms of the deal we had no authority on the show," explains Davis ruefully. "We all had a hard time with Leger, but Andy did a great job under the circumstances."

"From some respects it’s still a dark cloud for me," concludes Morahan, "but when I look back now there are things that I quite enjoy, so it can’t have been all bad. It’s a funny franchise because it’s so messy, although it actually made for some pretty decent TV."

The television series, at once larger and more intimate than the films, is absolutely the key to Highlander’s longevity. Beginning in 1992, it was filmed in Canada and France (with funding from Canada and all over Europe), lasting for 119 million-dollar episodes over six seasons. "The series was our saving grace," says Davis. "Through all the years the films might not have been appreciated by the fans, and rightfully so, the series was extraordinary."

After a single appearance from Lambert, the series shifts its focus to Adrian Paul’s Duncan MacLeod, and the hurdle of the world being once again full of immortals is tackled by the new revelation that potential immortals exist; their immortality only triggered if they die a sudden, violent death. A rocky first season struggled with a formulaic decapitation-of-the-week format until the arrival of writer David Abramowitz and producer Ken Gord, who grasped its potential immediately. "It was a thinking-person’s action show," says Gord, "and it was the complexity of its mythology that the fans loved."

From this point on the films became almost peripheral to the franchise: the fans that attend the conventions are all about the series. "The problem with all the sequels," says John Mosby, PR guru for Highlander Worldwide, "is that they were always hugely action-focused, despite the budgets not being able to cope. The series demonstrated that that wasn’t what the fans actually wanted." The original action ideas were designed to appeal to a young male demographic, but the show’s romantic, emotional side gradually attracted an audience the producers hadn’t realised existed: namely women. Ken Gord was also surprised to learn that in North America the show was playing to adults, rather than adolescents, whereas in France "no adult would be caught dead watching!"

Perversely, Mosby believes that the series’ erratic scheduling and lack of much in the way of promotion, also contributed to its cult success. Highlander floated around in syndication on various American networks, and non-satellite-subscribing UK audiences in random ITV regions may have caught it in the middle of the night during the mid-to-late 90s. "People found it by accident," says Mosby, "and that gave them a sort of personal investment in it."

The series ended in 1998, but the franchise continued. 2000’s Highlander: Endgame, the fourth feature film, attempted the trick of rebooting the movies by handing over from one generation to the next. Christopher Lambert returned for the final time, alongside Adrian Paul, in an ambitious project that tried its utmost to clean up the tortured continuity.

"Christopher was great," says Paul. "We were both a little bit older by that point, or should I say more mature? Nah..." The shoot was beset by all the old problems though: disagreements over a script that had audiences splitting their allegiance between two main characters; Bruce Payne (playing villainous immortal Jacob Kell) falling ill, causing production in Romania to be halted and moved to London; Adrian Paul’s injured shoulder which made three months of fight choreography difficult; and further delays in London which led to the film being finished in Luxembourg. "It was just prolonged pain," says Paul, "and it never seemed to end."

Post-production was no easier. Having worked as effects editor on the original film, Chris Blunden found himself back in the fold as principle editor on Endgame, only to be replaced. Director Doug Aarniokoski produced a rough cut which, according to Blunden, "Bill Panzer simply wanted re-done. Doug understandably didn’t feel he wanted to do that, so they put five new editors on it and made it virtually incomprehensible."

Fan pressure led to the eventual release of both the producer and director’s cuts on DVD, much to Aarniokoski and Blunden’s annoyance, since their version remained unfinished. Despite this however, Endgame, on a budget of $14m, raised revenues for Miramax of around $50m.

Blunden was lured back for fifth movie The Source in 2007, for more of the same. "I was asked by the completion company to try and pull it together, but it was like all the others: three quarters of a film. Brett Leonard (The Lawnmower Man) was full of big ideas that he was going to reinvent the series, without any money or much of a cast or a decent location or good visual effects, but it turned into the usual fight because he didn’t have final cut. It was taken away from him and, once again, re-edited into something else."

"It had visual style," says Paul, "and the characters were well defined. But the movie story [a lackluster dystopian sci-fi involving the source of the immortals’ power, and a gang of forest-dwelling cannibal pirates] seemed unfinished. There was no real resolution or understanding as to what the source actually was, and so the movie fizzled away."

Mosby concurs, but is keen to defend the producers: "Davis-Panzer got a lot of criticism over the years, but it’s important to understand that without them, there’d have been no Highlander. They would compromise a lot just to get things in front of the cameras, but they got the films made, which is no mean achievement."

"We’re the guardians of this franchise; it’s our baby," says Davis. "Don’t make us sound like rug salesmen!"

The Source actually premiered on the SciFi Channel to respectable ratings, but a mooted new trilogy never materialised. The conventions continued to sell out modest-sized venues, the series continued to find an audience on DVD and online, (scoring 11,000 downloads a day from streaming website Hulu) and a complex collaboration with the Japanese Imagi Animation and Madhouse Studios yielded the critically acclaimed Search For Vengeance in 2006. But the prospect of new Highlander in the core series seemed slim.

Except that, if all goes according to plan, Highlander will come full circle in 2010 with a mega-budget remake of the original. Summit Entertainment have licensed the rights from Davis-Panzer, a "rather grandiose" script has been produced by Iron Man scribes Matt Holloway and Art Marcum, and according to Davis "we’re about to lock in a director, and the budget, though this may sound like producer’s juice, is around $100m."

"Why?!" asks an incredulous Russell Mulcahy, only to rally admirably: "Actually that’s not a bad idea. They can make it a bit more hip: take out all the Queen! I wish them the best of luck with it!"

Six years later, the Highlander remake remains in development. StudioCanal's new 30th-anniversary 4K restoration of the original film is out on Blu-ray on July 11.