A mild-mannered English professor in a previous career, Wes Craven became part of the vanguard of filmmakers - along with George A. Romero, John Carpenter and Tobe Hooper - who seized upon and reinvented the horror movie in the 1970s. The director of some of the most iconically terrifying films of the last few decades, his name became synonymous with his chosen genre: a genre from which, with only one real exception, he never deviated. "You realise you're doing something that means something to people," he once told his contemporary Mick Garris. "So shut up and get back to work.” With his recent death that work has, tragically, now been curtailed. Here's Empire's guide to his impressive cinematic legacy.

Essential Viewing

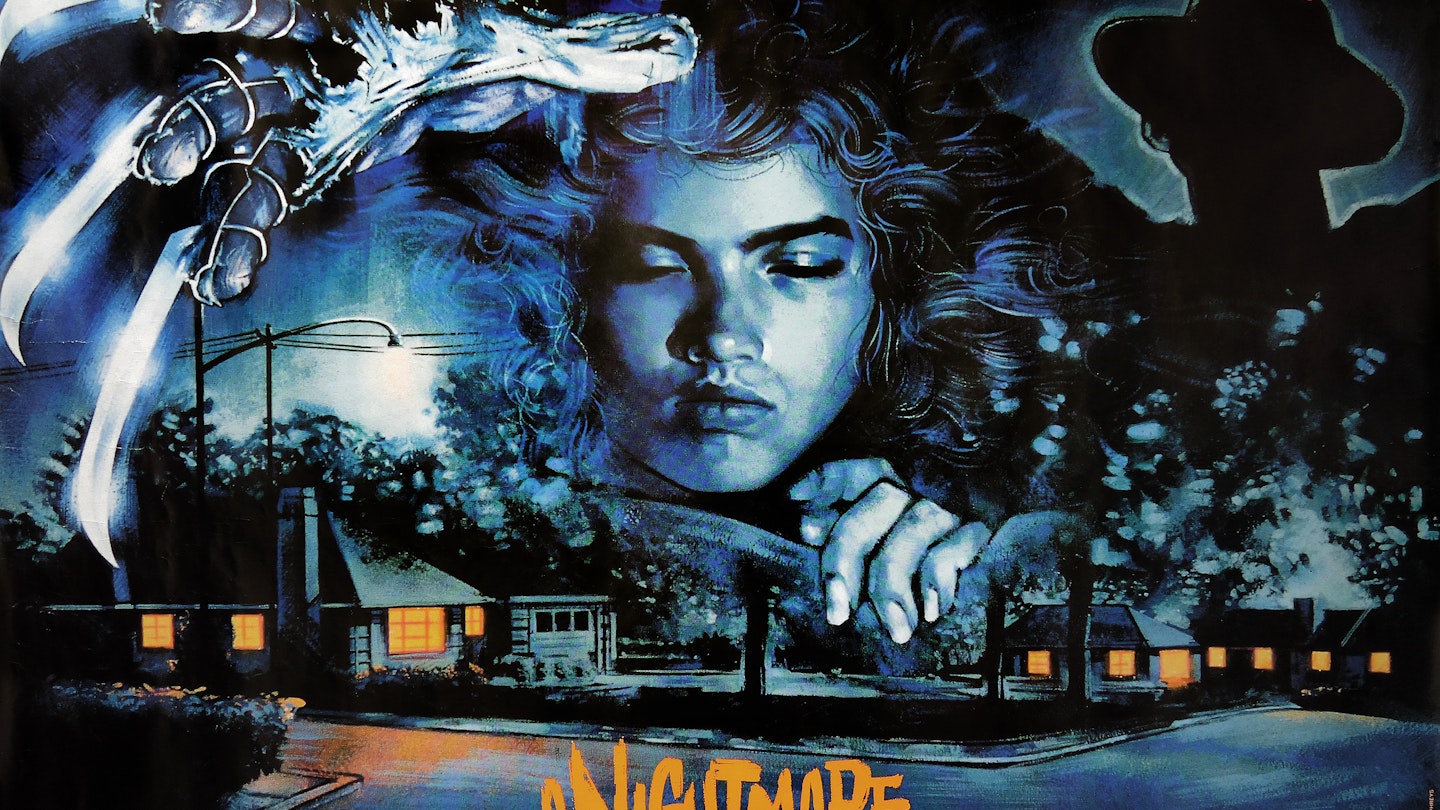

A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984)

Twelve years into his career, Craven's fifth movie (not counting TV work) created an indelible impression on an entire generation. The tale of a child killer, himself murdered by a lynch mob and then returning from beyond the grave to persecute the kids of his assassins through their dreams, was strong enough in itself. Then there was the iconic Freddy Krueger, wearer of that glove (and hat, and sweater), played unforgettably by Robert Englund (an eleventh-hour replacement for - unthinkable now - David Warner). The original great Freddy moments are his strangely elongated alleyway introduction; his loom through a solid wall; his rising up under a bed sheet; and his glove menacing an oblivious Heather Langenkamp in the bath. But while his presence looms large over the proceedings, Freddy is seen comparitively rarely in his first outing, and many of the scares that people remember (or can't forget) function without him: Johnny Depp swallowed by a bed that turns into a geyser of blood; Amanda Wyss defying gravity to be smeared around her bedroom; Wyss again, in a body-bag at school; the marshmallow stairs. Craven understood bad dreams, and A Nightmare On Elm Street was, and remains, extraordinary. The one and only - except, of course, that there are nine of them. Freddy became a stand-up comedian over the course of the sequels and TV series, but Craven would rehabilitate him - for a time - with his New Nightmare.

**Scream **(1996-2011)

A decade later Craven did it again: terrorising a new generation and giving the entire horror genre the kick up the arse it so desperately needed. In cahoots with screenwriter Kevin Williamson, Craven presented a cast of characters who were hip to exactly the type of movie they were in: understanding the rules of the genre and discussing them even as they were stalked-and-slashed themselves by the "Ghostface" killer. The meta fun continued throughout the sequels, where the Stab franchise arrived to mirror the "real" events; follow-up tropes were pored over; and the whodunnit aspect revealed a different murderer (or murderers) each time: no zombie resurrections here. And again, there were great individual moments, functioning despite the clever-clever context. Empire readers point again and again to Rose McGowan in the garage door; the climb through the car in Scream 2; and of course, the first ten minutes of the first Scream, where Drew Barrymore gets a phone call and the apparent star of the film - the biggest presence in the trailer and on the posters - is immediately killed. All bets were off.

**The Hills Have Eyes **(1977)

Craven's unrelenting second theatrical feature took, very loosely, the Scottish legend of Sawney Bean and transposed it to the Nevada Desert, where a family of cannibals terrorise the sparse locals and seize the opportunity for some fresh meat when a family get stranded. Like The Last House On The Left, this is a truly gnarly, grainy, almost verité affair. It's pacier than its predecessor, but deals with similar issues, principally the violence not only of the villains, but of our "heroes" who are willing to become monstrous themselves in order to survive. And again with the indelible moments: the cannibal attack on the women (and the baby, and the parrot); the crucifixion and burning of Robert Houston; the final freeze-frame; Michael Berryman. Craven himself directed a cash-in sequel eight years later, but disowned it. Alexandre Aja's 2006 remake on the other hand - for which Craven retained producing and screenwriting credits - is surprisingly strong.

Highly Recommended

The People Under The Stairs (1991)

The berserk saga of an LA ghetto kid ("Fool", played by Brandon Adams) who stumbles into the house of Mommy and Daddy Robeson (Wendy Robie and Everett McGill) and finds a community of cannibal children hiding in the cracks. Gimp-suited craziness abounds. Many have interpreted the film as a bitter satire on American society with the Robesons representing Ronald and Nancy Reagan, but Craven always denied that political reading. He said the film came to him in a dream, so maybe his subconscious was doing the satirising for him.

**The Serpent And The Rainbow **(1988)

Flawed but fascinating, this is a zombie film based on a work of non-fiction: Wade Davis' book investigating Haitian Voodoo and, specifically, the case of Clairvius Narcisse, who apparently returned to life after his death and burial. Bill Pullman takes the Davis role as Harvard ethnobotanist and anthropolist Dennis Alan, whose investigations for a pharamaceutical company lead him to the process whereby witch doctors drug victims into the grave only to "resurrect" them later as suggestible shadows of their former selves. The deviations from the book are numerous and the basis in fact dubious, but it's a powerful film. In particular, the part where Pullman is himself drugged, collapsing to the ground pleading, "Don't bury me; I'm not dead," is one that'll stay with you. As will the sequence when Zakes Mokae does in fact bury him alive – with a tarantula to keep him company.

**The Last House On The Left **(1972)

Refused a certificate in the UK for decades, Craven's ferociously bleak debut is now readily available, and lost none of its disturbing power while it was away. It certainly isn't for everyone. Appropriating the plot of Ingmar Bergman's The Virgin Spring, it deals with a gang of criminal sadists who kill two girls only then to rock up at the house of one of their parents. When the parents learn what's happened, impromptu revenge is served. It's a tough watch, particularly in the protracted scene of the girls' killing: not "just" a rape and murder, but a sequence of protracted sexual bullying and humiliation followed by horrific butchering. The viewer feels complicit, but part of what also makes the film so troubling is its jarring clash of tones: the horror sits alongside comedy cop skits; and there's knockabout bluegrass over the end credits. Craven would repeatedly revisit the notion of "good" people doing appalling things, and the house full of traps would reappear on Elm Street.

**Wes Craven's New Nightmare **(1994)

Craven stayed pretty hands-off as Freddy Krueger became an unlikely household name; his scares diluted by laughs (although he did write A Nightmare On Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, interestingly kicking off a new narrative trilogy in the middle of the series). But with Freddy's Dead apparently marking the final chapter, the director had an idea for taking Freddy back. New Nightmare's premise is that the films were a holding pattern for a genuine ancient evil, and with the series now over, that evil is now free in the really real world. Craven plays himself (Robert Englund and Heather Langenkamp played themselves too), directing a new Elm Street that stirs up the "Freddy" entity, putting the whole production in mortal peril. It was the start of the meta antics that would find blockbuster success a few years later with Scream and its sequels.

For The Fan

Shocker (1989)

One of two films - the other being House III - released within months of each other and involving a killer reviving to cause mayhem after being executed by electric chair. What this one lacks in Brion James it makes up for in Mitch Pileggi (The X-Files' Agent Skinner, and a Craven semi-regular). He plays the murderous Horace, whose experience in the Mercy Seat turns him into an electricity-being who can possess people. Peter Berg (yup, the same one that directed Hancock and Battleship) plays the youngster who has a mysterious connection to Horace. The madman is eventually harnessed by television, and goes on a rampage across the channels. Craven hoped this would start a new franchise. It didn't, but it's fun.

Deadly Friend (1986)

Kristy Swanson plays a girl-next-door it's probably a mistake to have a crush on. This was Craven attempting a dark romance and a more psychological chiller, adapting Diana Henstell's novel, which was not notable for its gore quotient. As the immediate follow-up to Elm Street, however, test audiences and studio Warner Bros. were equally dissatisfied with the slow-burn lack of violence, and so Deadly Friend was drastically altered in post-production, with some re-shooting providing more creative kills. Case in point: the much-beloved basketball offing of Anne Ramsey (see above).

Deadly Blessing (1981)

Post-Hills Have Eyes and pre-Elm Street, Craven gave us this saga of Hittite (like the Amish, but more serious) farmers plagued by a murderous incubus. Ernest Borgnine and Hills veteran Michael Berryman are among the cast, along with a young Sharon Stone, who in the film's queasiest scene gets a spider dropped in her mouth. Original distributor Universal opted not to release it on completion, and it gathered dust until United Artists picked it up some time later.

Swamp Thing (1982)

This is what a comic-book movie looked like in 1981. Two years before Alan Moore revolutionised the comics with his seminal run for DC, the Swamp Thing was still ripe for a cheap knockabout starring a man in a rubber suit. Ray Wise is the unfortunate creature, formerly Dr. Alec Holland, before he's transformed by his unlikely bayou accident. Adrienne Barbeau is the love interest, and the urbane Louis Jourdan is bad guy Anton Arcane. Look out for David Hess (Last House On The Left's Krug) too, as henchman Ferret. Everyone plays it more-or-less straight, but it's still camp as hell. As an experiment to prove Craven could do mainstream, it doesn't really work. Its effects didn't even hold up well at the time, and its action is hopeless - but it's not without its charms.

Red Eye (2005)

Efficient psychological thrills here, proving that Craven could do mainstream after all. Red Eye is a likeable two-hander for Rachel McAdams and Cillian Murphy, sharing an increasingly claustrophobic flight to Miami, where Murphy turns out to be less charming than he initially seemed: the moment when he "transforms", in particular, is superbly unnerving. Plenty of twists too, although we're on more familiar territory once the plane actually lands and the film becomes a stalk-and-slash around McAdams' house.

For The Completist

Vampire In Brooklyn (1995)

A curious chimera, negotiating the treacherous line between horror and comedy, with the result neither particularly scary or especially funny. It's almost as if Craven was striking out for John Landis territory, but this is no American Werewolf In London (or even Innocent Blood). Eddie Murphy - who gets a story credit - plays multiple roles, as he had in Landis' Coming To America and would again in The Nutty Professor, Bowfinger and Norbit. Principal among them is bloodsucker Maximillian, in New York looking for the power that'll help him live beyond the next full moon. Kadeem Hardison, Angela Bassett and Zakes Mokae (also in Craven's The Serpent And The Rainbow) co-star.

Music Of The Heart (1999)

The one real non-genre anomaly on Craven's CV: a drama based on the true life story of Roberta Guaspari, previously the subject of a documentary that caught the unlikely director's eye. It's the inspirational story of a divorced (white) mother bringing classical music to the (ethnic minority) kids of a Harlem school. A bit like Dangerous Minds but with music instead of poetry. A bit like Mr. Holland's Opus but with Meryl Streep instead of Richard Dreyfuss.

Cursed (2005)

Jesse Eisenberg, Christina Ricci, Joshua Jackson and Judy Greer star in this werewolf horror-comedy which, even more so than Deadly Friend, was (ahem) cursed by calamitous production problems. Skeet Ulrich, Mandy Moore, Omar Epps, Illeana Douglas, Heather Langenkamp, Scott Foley, Robert Forster, and Corey Feldman were all cast at one point or another, and none of them were in it by the time the film emerged, battered and bloodied, from more than a year of script rewrites and shut-downs. The best you can say about the final result is that it's easygoing but throwaway.

My Soul To Take (2010)

Craven's first film as both writer and director since New Nightmare is a straightahead supernatural slasher, abandoning the self-aware for the purely generic. A cast of relative unknowns endure the curse of the Riverton Ripper: a serial killer who disappeared 16 years ago, but now appears to be back. Thankfully this far from vintage effort wasn't Craven's last as a director. His final word on the subject of horror was a Scream.