As far back as we can remember, Empire has been obsessed with GoodFellas – Martin Scorsese’s super-slick, multiple-decade-spanning mobster epic, packed with iconic performances, legendary dialogue, and the technical bravura that Scorsese does like nobody else. For its 30th anniversary, read Empire’s original exhaustive 1990 interview with the filmmaker himself, all about the creation of the ultimate gangster flick.

———

This article was first published in Empire Magazine{

"It was, like, 3:30 on a Saturday morning, October of 1963," recalls Martin Scorsese, settling back in his chair. "Myself and Joe, who was my closest friend at the time, we were in a car, and we decided we didn't like the fellow who was driving us around. So we asked him to drop us off on Elizabeth Street – he lived on the street too. He was an off-duty cop, and he had a gun with him all the time and I didn't trust that. Much better off with a couple of wise guys. So he drove down the block, there was another car parked right in the middle of the street, and a guy talking to some other guy in a parked car, big black car. And he got into an argument with them, made a big deal out of his being a cop. And the fellow in the car suddenly says, 'I'm not moving, I'm in the middle of a conversation'. Suddenly the whole thing turns into a Western. And the guy we are with pulls his gun and says, 'I'm a cop, move'. And the guy replies, very calm, 'Do you really wanna pull the guns?'. And, like, Joe and I are still in the back seat. Anyway, the guy pulls away, the off-duty cop drops us home and drives off and all of a sudden a black car drives up next to him and they just fire a whole bunch of shots into him. God knows where the shots would have hit us, just going for a ride with this idiot who had to act up a big deal because he was a cop. We could have been killed that night. But you learn, you learn to feel your way around. You see somebody being too stupid and you just say, 'Oh no, I'm going home'..."

The incident just recalled by the 48 year-old Martin Scorsese could quite easily come from his new feature film, the epic GoodFellas. This last week, when his 14th movie opened in the US, belonged to Scorsese. Reviewers were, for once, unanimous in their praise, comparing GoodFellas, favourably, to Raging Bull, the critics' perennial choice as Best Film Of The '80s. Indeed, the sole bone of contention appeared to be whether or not GoodFellas is "better" than Raging Bull or simply "just as good".

There is a certain magic in filmmaking, but you have to go through hell to get there.

"That level of criticism, I can take," cracks Scorsese, obviously thrilled with the various accolades heaped upon him in the last few weeks, most notably Best Director prize at the Venice Festival.

An interview with Scorsese is an experience unto itself. The man is small and wiry, his metabolism high-speed, pumping you with words and ideas faster than a machine-gun. His conversation jumps all over the place, from this director to that (he does a mean impersonation of John Cassavetes), from his own films to everybody else's ("Peeping Tom is a film about filmmakers"), to the beard he has just shaved off ("After 16 years, I just discovered the rest of my face"), to Italy ("A whole different attitude. Life is more important than appointments"), and always back to films ("Every time you start one, you realise how much you really don't know. It's just awful").

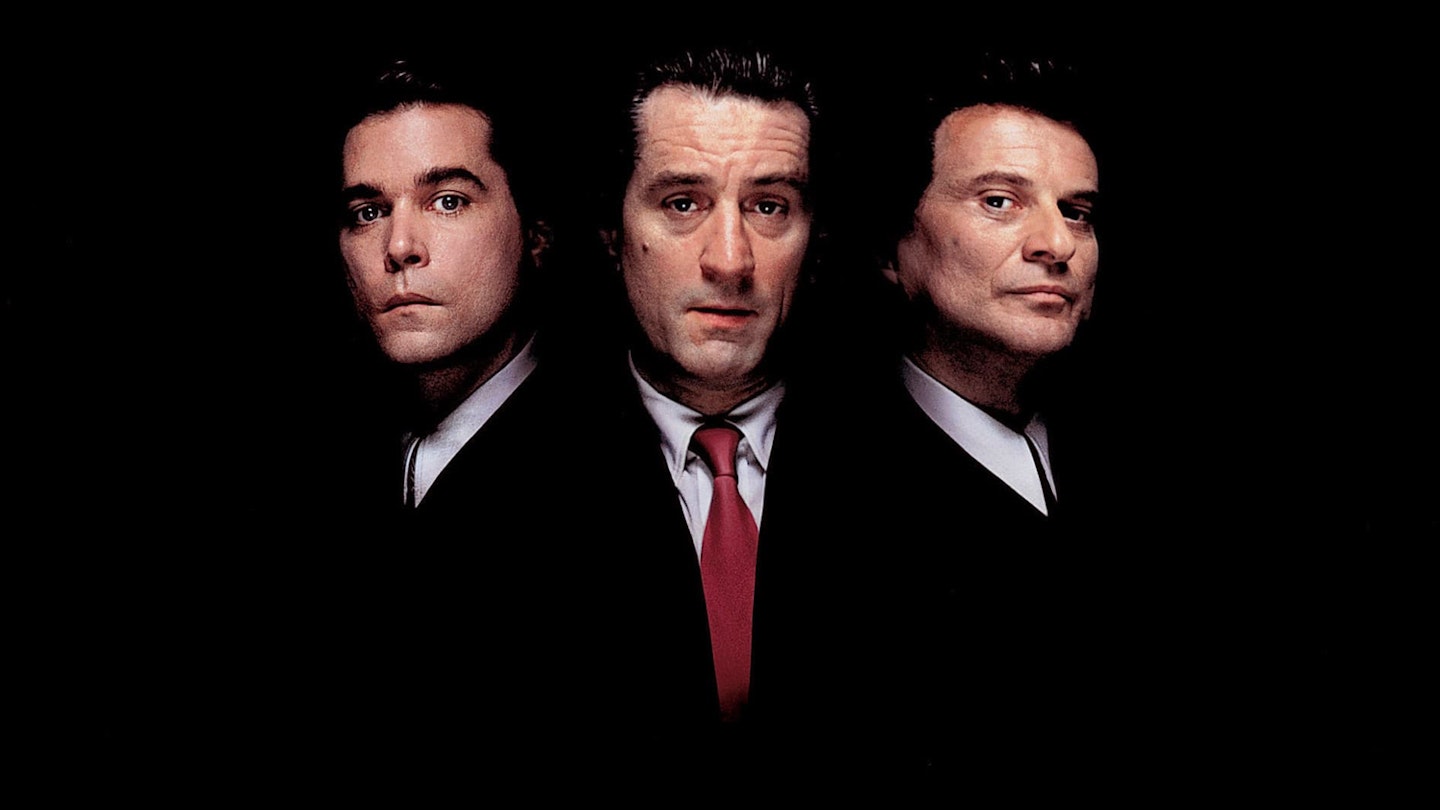

And, of course, GoodFellas, his movie adaptation of Nicholas Pileggi's book Wiseguy, the true account of the exploits of Henry Hill – played by Ray Liotta in the film – a half-Sicilian, half-Irish crook who, at age 14, began an extraordinary life of illegal activities, ranging from construction rackets to extortion, hijackings, arson, the then-forbidden Mafioso territory of drug smuggling and, eventually, murder. Some 30 years on, married and as high in the mob ranks as an Irishman could go, Hill entered the US Federal Witness Protection Program – turned super-grass and promptly dropped the dime on buddies Paul Cicero, played by Paul Sorvino, and fellow Irishman Jimmy Conway, memorably portrayed by Robert De Niro, like the director here back to his very best form. Scorsese has, of course, made many films about gangsters and assorted low-lifes (Mean Streets__, *Taxi Driver__, Raging Bull, *The Color Of Money) but has consistently said that as an Italian-American he would never make a movie on the Mafia, or the good fellas, as they prefer to be known.

"I know," he replies, "but it's a bit different here. 'Cause it's not that. When I read the book, and then when I started writing the script with Nicholas Pileggi, we gave it such a structure that it seemed to me an exciting film to make. That it would be too bad not to make, too bad for me not to make. It's an epic, insofar as it covers 25 years, from 1955 to 1980."

Indeed, Scorsese goes so far as to see his film more like a modern version of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. "Someone totally innocent at the beginning who goes deeper and deeper into crime, and pays the price in a way – but that's for the audience to decide."

Whatever his reluctance to publicly link his film with the mob, however, it is clear that Scorsese is no stranger to the ways of the real-life good fellas. In addition to the harrowing incident recalled earlier, he has a whole wealth of childhood memories to call upon. "What fascinated me most were the details of everyday life," he says of his salad days in New York's legendary Little Italy area. "What they (the local good fellas) eat, how they dress, the nightclubs they go to, what their houses look like, and how, around that, life organises itself, day by day, minute by minute, Their wives, their kids."

The ritual of filmmaking is akin to a religious ritual.

He vividly recalls a picnic from his childhood. "There were all these men near the bar," he remembers, "eating sausages and pepperonis, and as usual, kids everywhere, running around to get a sausage for their dad or something. And years later I understood it was a 'family' meeting. Those guys were working, they were doing business. But at the time we didn't know. They all looked just like... uncles."

Born in the New York City borough of Queens, in a small community called Corona, the young Scorsese and his family moved in with his grandmother on Elizabeth Street in the heart of Manhattan's Italian community. "My father had run into some difficulty at his work, he lost a good deal of money and we had to put our furniture in storage when we moved. There were three rooms in my grandmother's house, one for my grandparents, one for my mother and father, one for my brother and me. We lived there for six months, then got our own rooms down the block on Elizabeth Street. It was only 20 years later, after my brother got married and I moved out in the '60s, that my parents moved... across the street."

Separated from Chinatown by Canal Street, Little Italy is a tiny neighbourhood but, according to Scorsese, one with its own highly complex geo-socio-politics. "The Sicilians that emigrated came from small towns," he explains. "My grandfather came from Polizzi Generosa. All the people from Polizzi moved to Elizabeth Street – all in one building. Then, as soon as they could secure more rooms in the same building, they'd bring in people from their village. Then there were people from Cimina, which is the hometown of my grandmother on my mother's side. Same thing: they'd have a few buildings down the block. Very rarely would a Sicilian live on Mulberry Street – that was for the Neapolitans. So what they did was import the village mentality and the village social structure to Elizabeth Street."

What fascinated me most were the details of everyday life.

In this feudal structure, according to Scorsese, it was normally none other than the Don who settled any problems. "For instance, one of my aunts eloped," he recalls. "For my grandfather, she was dead, didn't exist anymore. For six or seven months, we wore black at home. Then, one day, the don of the block representing my grandfather's hometown came up for coffee and a talk, because my grandmother had intervened. She had asked the Don to convince my grandfather to let up on this attitude towards his daughter. She wanted her daughter to be allowed back into the home. And the Don worked it out. That's the kind of settling he usually did."

For Scorsese, this increasingly outdated way of life obviously still holds a certain appeal. "This summer, I went back to Sicily and visited both towns," he explains. "And it's still prevalent there. For those towns, it works. For three or four buildings on Elizabeth Street, it works. For the people who came here and worked as labourers and opened grocery stores and sold things in the streets, for most of the time it worked. When you start to go bigger, when the Don wants to take over the West Side, then it becomes a problem. I don't necessarily justify it, but I understand. I understand where it comes from, I understand why they distrust governments, and especially police. Different culture. But when you're eight or nine years old, that's your way of life. There is no such a thing as 'outside that block' or those two blocks, three blocks. Everything else outside is a fantasy. I was 18 when I went to the Village, crossed over to the West Side and went to New York University. We had everything we wanted on the East Side. We hated the West Side."

Many years later, at the time he was married to Isabella Rossellini, Scorsese went back to Italy to live for a period. "I liked the style of living," he says of that time. "Taking it easy, moving at a certain pace. But one thing I realised when I lived in Rome with Isabella was that I'm American..."

As a child, Scorsese had asthma. Nailed to his bed for two or three days in a row, he would draw little pictures – his first storyboards, which he still has – and look outside the window, longing to belong. "The kids that I became friends with lived on Elizabeth. And we'd get into fights – usually they'd hit on you, punch you a few times in the arm, and that's it, just to test you. And I'd say, 'Don't touch me, I have asthma'. If he was a tough kid, he'd say 'It doesn't matter' and just hit me anyway. But I was able to stand up to them, able to take the punishment off them. They'd like that. They liked the fact that I was being able to be with them and pass certain rituals, passage of rites, and take pain. I'd make them laugh, I'd organise their parties, I'd evenprogramme the music at their dances – I always opened with Chuck Berry. A real bona fide Sicilian (laughs)."

Blessed with a mother who adored motion pictures, Scorsese was not slow in discovering the delights of the local picture house, beginning with King Vidor's Duel In The Sun. "The ending terrified me," he recalls. "I ended up under the seat. The sun was boiling up there, Jennifer Jones was shooting at Gregory Peck – they loved each other so much they killed one another – and all the time she's doing all sorts of gyrations on the screen, expressing great lust, shouting, 'I'm trash! I'm trash!'... It sort of laid out the course of my entire love life."

Condemned from the pulpit, Duel In The Sun was one of the few films rated the forbidden "O" by the Catholic Church that Scorsese dared to see. "Rossellini's Miracle I didn't see," he says, "'cause I was too young to understand – I was eight – and I didn't even know about the controversy. A few years later it was Otto Preminger's The Moon Was Blue, because they used the word 'virgin' and didn't mean The Virgin Mary. Elia Kazan's Baby Doll was condemned in 1956. Would you believe I saw it for the first time only in the mid-'80s?" Eventually, troubled by this conflict between his faith and his interest in films, the budding director took counsel from his parish priest. "I explained to the priest – in confession – that I just had to see Ingmar Bergman's Smiles Of A Summer Night. And that having seen it, I hadn't found anything so difficult about it. And the priest said, 'Look, for the masses, we can't allow this sort of thing. But if it's your work...' I mean, how many guys from the Lower East Side were going to see Smiles Of A Summer Night?"

Gradually, Scorsese's adherence to the teachings of the Catholic Church – he even tried to get into a Jesuit university but poor grades sent him to NYU instead – began to crumble. "I learned about the streets as opposed to an edifice called the Church," he says, "because, living in the neighbourhood I'd see some really tough bastards do some really rotten things, then go to church on Sunday and everything was okay. And the moment they'd step out of the church, they'd start acting the same old way. I couldn't see how you could take a Christian ethic and actually put it into practice in that world."

Inevitably, however, some of that old attraction, at least to the dramatic rituals of the liturgy, still lurks deep within him and his work. "Never left," he agrees. "When I made The Last Temptation Of Christ, the actual making of the film was like a prayer, the way certain composers in centuries past dedicated their work to God. And the ritual of filmmaking is akin to a religious ritual. 'Slate', 'Action', 'Cut'... You have to have a kind of rigour which is religious, just to plough through, to keep going. My father often says, 'Marty, every picture to him is the worst experience of his life. But he's having a ball while he's saying it'. And he's right. There is a certain magic, definitely, but you have to go through hell to get there."

In addition to GoodFellas, Scorsese is also currently expending his energies on his own recently created production company, with Stephen Frears' adaptation of Jim Thompson's hard-boiled thriller The Grifters the first product to emerge. Still to come are John McNaughton's Mad Dog And Glory (McNaughton, a relatively unknown director, came to Scorsese's attention with his first feature, Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer. "I was so disturbed by Henry that I slept with the TV set on," says Scorsese), Antonioni's The Crew, and a remake of J. Lee Thompson's Cape Fear. And then, of course, there is the much talked-about documentary on Italian fashion supremo, Giorgio Armani.

"It's really the idea of Milan," explains Scorsese, "the city of Milan, hiding such elegance. Milan looks very fiat, but when you enter the courtyards, everything opens up. And then, of course, when you go inside the villas, they're quite extraordinary. The style. And this film is about style. About a man with style."

A man with style from a terribly impoverished background. "Yes, I had no idea. He is such an elegant man. I didn't know until he started talking about it and introduced us to his parents. They were always well dressed but the mother made the clothes for him. She taught him. And he's self-made. He created his empire out of his energy, and his vision."

Not unlike, in fact, Martin Scorsese, the boy from Little Italy now regarded by many as the finest film director in the world. The man who, when busy editing Raging Bull, was sent a message by cinematographer Michael Chapman, quoting a line from one of Scorsese's all-time favourites, Peeping Tom, the line that says, "All this filming isn't healthy".

"Maybe it isn't," says Scorsese now, when reminded of the incident. "But who cares?"

This article was first published in Empire Magazine{