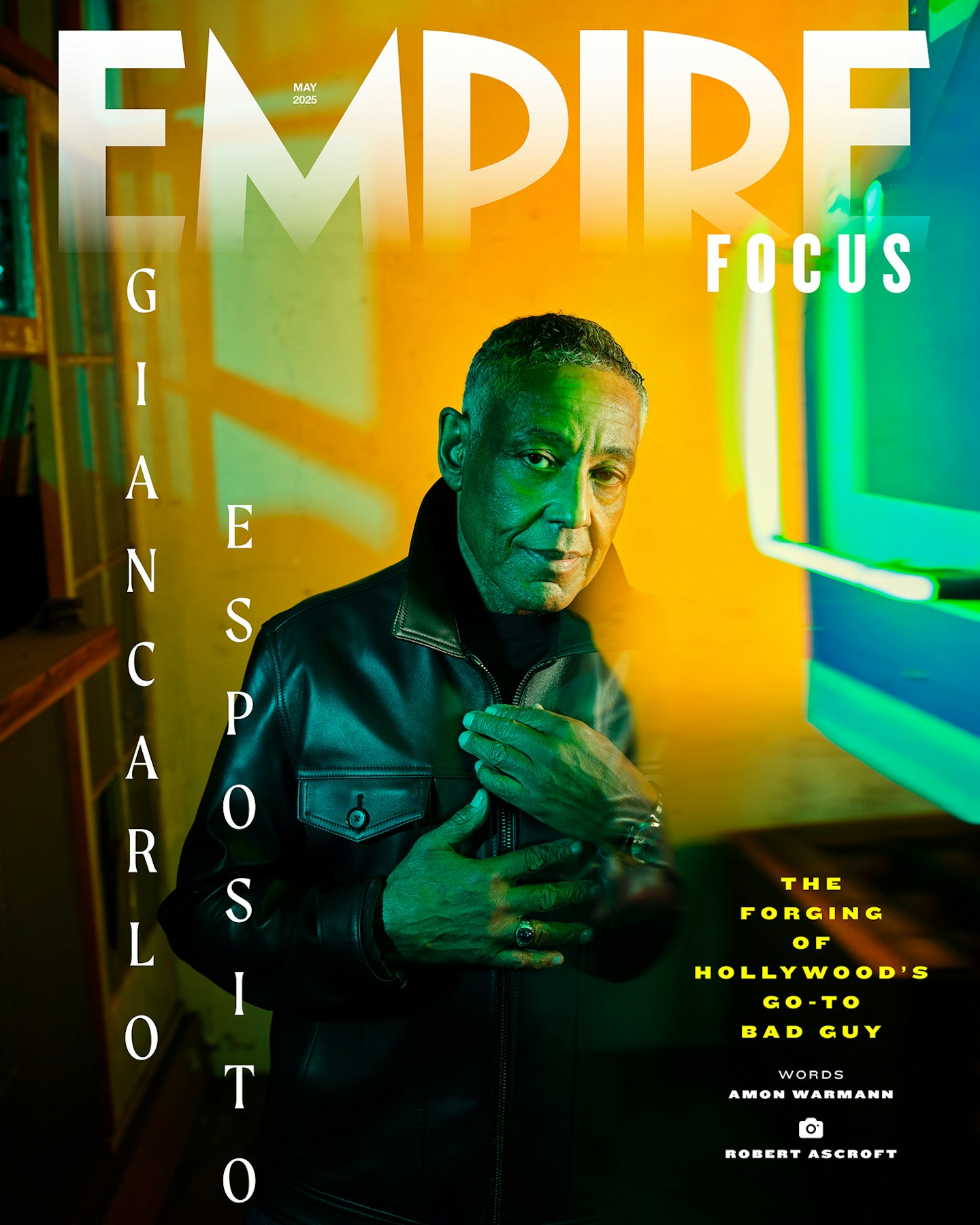

From Breaking Bad to The Mandalorian and now The Electric State, Giancarlo Esposito’s characters are as strong-willed as it gets. As we discover over a no-holds-barred conversation, this is no accident – and no coincidence…

“My intention is to sit here and tell you all of who I am.”

It’s not a sentiment one often hears expressed in an interview. It’s an even rarer thing for it to be meant, and felt. But that’s exactly the brand of direct, open honesty you get when you talk to Giancarlo Esposito. It’s part of his nature.

Esposito has long been that knowingly reliable character actor who would always improve a project by a factor of approximately 27 per cent every minute he’s onscreen. Roles in iconic films like Do The Right Thing, The Usual Suspects and Malcolm X were early indicators of his limitless talent. But it was his turn as the calm and collected drug kingpin Gus Fring in Vince Gilligan’s hit drama Breaking Bad (and later, Better Call Saul) that kicked his sputtering career into high gear, earned him much-deserved acclaim, and changed the trajectory of his life. It was the first of many roles that cast him as classy, complex, and formidable bad guys in everything from The Mandalorian to The Boys and, more recently, Captain America: Brave New World and The Electric State.

In conversation, Esposito is far less intense than the characters he tends to play: our tête-à-tête features spot-on impersonations of Spike Lee, Laurence Fishburne and Anthony Hopkins, the occasional in-character line reading, and a whole lot of truth-telling on the industry, and himself. After nearly half a century in the business, he’s earned the right to be as sure of himself as he is. And with a memoir on the way, he’s more willing than ever to talk about “the good, the bad, the ugly, and the treacherous” moments of his singular journey.’

EMPIRE: Spike Lee calls you G-Money. Where did that nickname come from?

GIANCARLO ESPOSITO: Do The Right Thing came up and Spike offered me a certain amount of money. I was willing to take it until I found out that there were others in the cast who were making more. I, with courage, said, “Spike, come on now. That’s not gonna cut it.” And he laughed at me, and we went back and forth. Then he came back and said, “I got you.” I said, “Where’d you get it?” He said, “I took it from my sister. Got it from Joie’s pile!” And I said, “Oh man!” But he said, “It’s cool!” and then he said “G-Money!” and that was it. I think it was a really great sign of respect, and then that endeared us to each other. Spike has taught me so much, I gotta tell you. He’s an incredible businessman, and he does it with grace and aplomb. It was at that point in my life that I realised there’s a value on my talent.

Before that, he’d cast you in School Daze (1988). He’d seen you on stage on Broadway [in 1980’s Zooman And The Sign]. So this was very early on in your career. What did that creative partnership teach you?

It gave me confidence. It taught me to have courage and to be a creator. Spike had a vision. And when I could sit down with him and say, “I have ideas” and share that with him, he would respect that and take those into consideration in his rewrite. Allowing me to do what I felt like I could do the best was really a wonderful thing. So it was empowering.

He was writing images of African-Americans that we hadn’t seen or experienced [in cinema]. And these were whole and complete characters and people with a range of emotions, from the shame of the colour of their skin to the pride of it, to the looking down on light-skinned [or] dark-skinned Blacks… School Daze was all about that. And it allowed me to access and feel and exercise some of the feelings I had when I came to this country, being half-Italian and half-Black; I was mulatto. So Spike opened my eyes to understand not only the African-American historical connection that I come from and to honour that with grace and aplomb and cherish it and speak about it, but also my multi-racial ethnicity.

You worked with Laurence Fishburne in School Daze, and in the ‘80s you lived with him. Though he was going by ‘Larry’ at the time…

I’ll tell you right now, if you see Laurence now, don’t call him Larry!

"Prior to Breaking Bad, I was bankrupt with two kids and another one on the way."

Ha! Noted. You were two Black men in Hollywood trying to make it. What were those years like?

Laurence and I are like brothers. We recently worked together in Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis. [But] those [early] years were lean. Those years were of struggle. He was on a work search, I was on a work search. I met him on an audition for, I believe, [1979’s] The Warriors. He was living down on Vignes Street down in Los Angeles – which was a very rough neighbourhood back then – trying to rehab a loft that was unfinished. His idea was that we could share it and put it together. We literally had no door on the apartment, it was boarded up. We were climbing on little makeshift steps and cans to get in through the window. We literally had no bathroom. We were pissing and shitting in white buckets and throwing it out the window. It was a mess, and we were both trying to find work. We’re very close, but those years were hard because we were going up for the same kind of gigs, too. But we were never jealous of each other. We’d walk into the room for the same role but it didn’t matter, because he and I both knew that if the role was for me, I would get it; if the role was for him, he would get it. We’ve been cultivating our relationship and work ethic for many years.

After making a few films with Spike, and other indie directors, you had a period in the early noughties when things weren’t so great. How were you feeling about the work? Was your life impacting your career choices?

At that period of time, prior to Breaking Bad [in 2009], I was bankrupt with two kids and another one on the way. I had to take everything I could get, I was desperate. I was married at the time and my former wife looked at my career and said, “Don’t take anything that would compromise you, no matter what reason, even though we’re in this struggle.” It was a very difficult moment in time where I was considering knocking myself off, because my former wife’s father was in insurance, she had some insurance on me, and at that point in time, I didn’t think that survival was going to be an option for me, because I had these children who I wanted to survive me. And if I couldn’t provide for them because I couldn’t get work, then it was a problem.

What was the turning point?

Those horrible thoughts went through my brain, until a neighbour gave me a book called Who Moved The Cheese?, and I reconnected to the warrior part of me that is about what we do as men: you know, women are [at] home, nurturing the children; men are the hunter-gatherers who go out and have to reinvent themselves over and over again to find that cheese. It was a book about a little mouse, and I was like, “Why is this guy giving me this book? I’m depressed. I need therapy, I need a job.” And I read this book, and I got the message of it. It was really a mental-health book. It was about me learning how to recreate my life and who I am, and it lit a fire in my belly. The fire was already there, but it allowed me some hope.

"I said, 'I must have a cape.' And I got the cape."

And then Breaking Bad came along. Even though it was an opportunity, I had to look at it as if I was the richest man in the world, and I wasn’t taking anything out of desperation or fear. And so I did a guest spot. And before I got off the plane from doing that guest spot – I’ll never forget it – the phone rang and they asked me, “Would you do another one?” And at that point in time, I couldn’t survive on guest spots, so I had to find my power to say [to myself], “I’m not doing any more guest spots, because they don’t pay me enough, but it also doesn’t feature the depth of my talent.” I said yes, and did another episode, and then they offered me a contract, which I really desperately needed, but it wasn’t going to pay out until the next season. And I said, “I can’t accept this – I’m willing, but if I tie it up now, it’ll preclude me from doing anything else in six, eight months, and I need to work now. Come back to me when you’re starting in the writers’ room on the next season, and if you really want to offer me a contract, I’ll consider it.”

What did that feel like?

It was one of the bravest things I ever did. I worked in-between, and they came back, and then I got the contract that I wanted, more than the contract that I would have had to accept out of desperation. So that changed my life. It allowed me to know that the power is in understanding your value and worth, but also in making the strategic decision that you have to make at a time in your career when you have to make that. Little did I know that that whole experience would change the complete trajectory of my career: when I went into season three, I didn’t think about anything but creating a character that you’ve never seen before. It was through conversations with Vince Gilligan. They’d offer me a contract and I’d say, “Can I speak to the creator?”

What were those initial conversations with Vince like?

I wanted to know what his ideas were for the character, and I wanted him to hear me that I didn’t want to play the bad guy of the week. I wanted to play characters that were deepened and cultivated. I said to him, “You’ve had a villain of the week that’s worked well for you, but now you need a formidable villain. You need someone to stand up against Walter White and be subtle and nuanced. Something you haven’t seen before.” And Vince was game for that. And I started to take the words away from being in a room with Vince suggesting stuff, to giving a performance in-between the lines that you could see. That was palpable. All that stuff that you could see in my eyes and feel in my heart. And week to week, they started writing in stuff that they saw, and it was the true testament of a really wonderful collaboration. And the turn of events came when Vince sat me down and said, “You know, the character you created…” I said, “Vince, you wrote the character.” “No, no, no, you created this guy.” I said, “Not without inspiration.” God has blessed me to be able to feel the nuance and the subtlety, to honour what’s written and take it to a new level.

With all the traction and awards attention you were gaining with Breaking Bad, did it feel vindicating? You bet on yourself and it paid off.

I don’t have time to be vindicated. I don’t have time to be in the glory of the feeling of triumph and success. Because I’m working my butt off! Look, yes, vindication comes from being able to be on a set every day. The day before yesterday, I was doing a movie in Utah, Salt Lake and in the middle of the scene I was like, “Wow, I’m working every day, somewhere else. I’m feeling this character come alive.” That’s the vindication. At one point I was doing Dear White People, The Godfather Of Harlem and The Boys all at one time. So I didn’t have time to sort of stop and go, “I’m back there with Gustavo.” Breaking Bad blew up to such a level that people would call me Gus on the street. And now people come up to me and call me a legend. I don’t know where to put that. I guess it’s because there are a number of characters I’ve created that stick with you. But that’s what I always wanted. So I don’t mind being called Buggin’ Out, or Gustavo, or [The Mandalorian’s] Moff Gideon, who was so wonderful to create as well.

How did Moff relate to what you’d been through in life? What did you like exploring about him?

I had a friendship with James Earl Jones; he inspired me my whole career. Mentors like Jimmy Jones and Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier, they were the actors that I wanted to embody, to encompass their feeling and power and joy and intellect. So I said, “I must have a cape.” And I got the cape. Moff Gideon, to me, was ultimately that young boy who never had any power, who was always questioned about the colour of his skin. “Are you white? Are you Black? Your hair is kind of curly?” And he then took on this place for me, where he was ultimately the power, not only because of his physicality but because of his brain. (Moff Gideon voice) “Assume I know everything.” Who says that? The way he spoke, and everything else which I was able to create in such a powerful way, empowered me to control the chaos around me.

When do you think we’ll see him again?

I don’t know. There is a big movie coming out that’s focusing on Mando and The Child. I can’t say it’ll be that. But I hope to be able to join that franchise again, because I think there’s more road for Moff Gideon.

Moff Gideon, Gus Fring, Stan Edgar in The Boys: they’re all control freaks. Is that something you’re drawn to when you’re considering characters? Have you noticed that commonality?

I feel like the characters I play have to have sacrificed something to be able to put them in the position to lead. It’s so funny you asked this question, because I realised I really can’t control anything except the way I see and feel, the way I react. I don’t want to be a reactor anymore. I want to react with kindness, grace and gentleness. I don’t want to fly off the handle. I have a very passionate personality. So in a way, some of these characters, who you call control freaks, are trying to be able to control themselves and the world around them, because they realise they really can’t control much. But the more they can control, it makes them feel comfortable. So each of the characters you mentioned have a piece of that within them, and I feel like if I didn’t look at those pieces in those characters and reveal them and have them be a part of the character, I wouldn’t be exorcising that within myself that wants the world to be a certain way. But it won’t be, because I can’t control it that way.

You recently joined the MCU in Captain America: Brave New World. You’ve been talking with Marvel for a decade, so what was it about Seth Voelker – aka Sidewinder – that made you want to play him?

It was supposed to come out in March of 2024, and they decided they wanted to make some changes. I was on the phone with [producer] Nate Moore, who prepped me to be, possibly, a character called King Cobra, which I loved, because if I’m walking around the neighbourhood, African-Americans go, “What’s up, King?” I love it. They call me King, baby! I mean, that’s the highest honour. But as it turned out, there [are other Kings] in the Marvel world, and this was connected to the Serpent Society – they were going back to the comics and trying to figure it out, and Nate said, “We can give you all the characteristics of King, but we think he should be Sidewinder.” And they spoke about creating a character that was really grounded, in a mercenary fashion. They wanted to ground the movie when they went back in to do some additional shooting, and their focus now was on this additional character. So it was a bit of a whirlwind for me. I focused myself and I went in there and knocked it out. And I’m hoping to be in this universe a little longer.

My work is my life. It’s not just something that I do.

You bring a grounded humanity to The Electric State too, as Colonel Marshall Bradbury, aka The Butcher. There’s always more going on underneath the surface of your villains.

With Colonel Bradbury, I felt like there was a character who had understood the world of politics and war and given it up, and was planting his garden at home and able to just be retired and be happy. He did his service, and he was really good at what he did, and he’s called back into service and is kind of fooled by a big corporate gentleman [Stanley Tucci’s Ethan Skate] who wants him to go after a rogue robot. My thing in my life is to have meritocracy, to strive to be the best at what I do with compassion, love, understanding and grace. The Butcher is the best at what he does. My work is my life. It’s not just something that I do. It doesn’t completely define me, because I have a life outside of it, but it’s affected by the imprint of my life: if I’m doing what I do on the level I’d like to continue to do, it lends to the depth of the character. So The Butcher, Colonel Bradbury, is a very special character for me.

In 2019 you said, “I would fight to the death to play Hannibal Lecter.” Is that still true? Did you get to talk about that with Anthony Hopkins when you made a guest appearance on Westworld?

Anthony Hopkins is an idol of mine. We never worked together directly on Westworld. When he was asked in an interview who might play [Lecter] again, without skipping a beat he said, “Giancarlo Esposito”, because he was, and is, a big fan of Breaking Bad, and he saw in my performance the ability to be able to play Hannibal Lecter in a way that he would approve of.

A knock came on my door when I was getting ready to go to set [on Westworld] and I opened it and there’s Sir Anthony Hopkins, bowing to me. And I looked up and caught those magnificent glistening eyes, and I took his hand and said, “Come in.” And we had a conversation in my trailer that lasted over an hour. We talked about art and humanity and acting and meditation and all these things. It overwhelmed me. We didn’t talk much about Hannibal Lecter at all. It was two forces of nature getting together. And I’ll never forget the subtleties of our conversation, because I felt like I’d met a human being I knew all my life. Another lifer in it because he loves it, will never stop doing it because he’s a creator. And so that was a beautiful moment. And would I play Hannibal Lecter? Yes, I would love to. It would tap into the deepest, darkest part of my being to do that, but I would be willing to do that.

What else do you want to do that you haven’t done before?

I want to play a romcom, because even though you’ve asked a lot of intense questions, I’m also very light of spirit and very funny! I did a comedy called Nothing To Lose [1997], which I thought was really good, but I want to do [more] comedy. I want to play a character who’s of a certain age who is looking for love. I’m a mature man who’s single and divorced and raising four daughters, [and] they’re like detectives. They’re looking at everything and everyone and everything that comes into my sphere because they want the best for me. So there’s a story there.

You’ve got a memoir coming up. What has the process of writing that been like? Why was now the right time to get reflective?

The process has been really wonderful, and painful, to go back through my life and career, my childhood and all else, to tell the truth about how I got to where I am today and where I want to go. It’s been an exorcism. I think now is the right time for me, because I think I’m more honest in my view of who I really am.

In my younger years, I was guarding the fact that I’m half Black and half-Italian, and I’d be selective about how I spoke about that, and to whom I was guarding. Acting has been, for me, a way of revelation, of revealing who I really am. I very rarely would talk about the pain of my life, from the divorce of my mother and father to my experience with drugs and alcohol, to my understanding now that the trauma that existed in my life from not being accepted as a an African-American man and half Italian in the high-school I went to, all the way up to not being accepted for who I am, but being looked at as a colour, created trauma in my life. I wanted to suppress it and push away by numbing myself, so I didn’t have to feel that the only time I really felt free was on stage, or creating a character that I was not, until I started to bring all of me to all the characters I play. Then I started to realise, “Your challenge is to allow all of that to go, to be acknowledged.” But you are as sick as your secrets, and if you’re hiding who you really are, then people are never going to really see it. So then that builds up this pain inside you, because you never feel like you’re really being honest with yourself or your family around you.

Now, in my case, my family is not only my family of origin, but it’s the family of my creation, my daughters, my former wife, my whole team. But then it becomes my audience. Because my audience know me from different facets of who I am, and [they] may think certain things about me, but if I’m not willing to share all of who I am with them, they’re gonna know me as Gus, as Gideon, as Stan Edgar, as Buggin’ Out. And that’s perfectly fine. But when my expression is at a point where I can be so honest about who I’ve been… because the fear is that all that I’ve been, I am still. But the truth is that that you we grow and we change, and then we become different. And within that growth, we then have to accept ourselves for who we are today.

So for me to realise that I’m not that, who I am today is not who I was yesterday, and that’s okay, then I can start to be really honest about all of me to all of you. Why? Because there are people in the world who need to see an example of someone who has worked through their trauma, pain, emotional upheaval, to have hope, because we’re not seeing hope from all aspects in our world right now. And so for me to be able to be the channel for people, and be the mirror for people to see some of that hope... it might give them the opportunity to find strength and to keep moving forward.

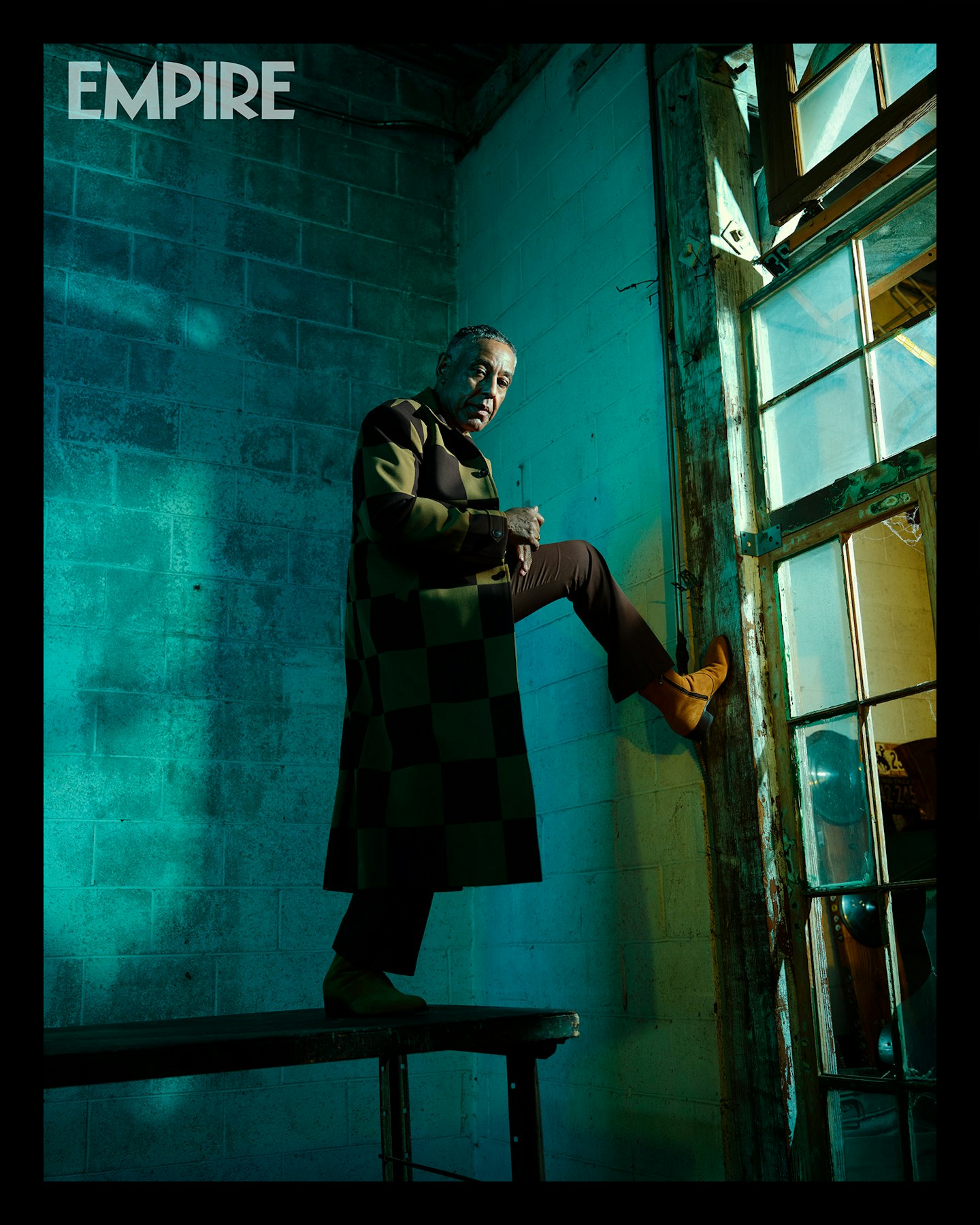

Originally published in the May 2025 issue of Empire. Giancarlo Esposito was shot exclusively for Empire in Los Angeles in February 2025, by Robert Ascroft. The Electric State is out now on Netflix.