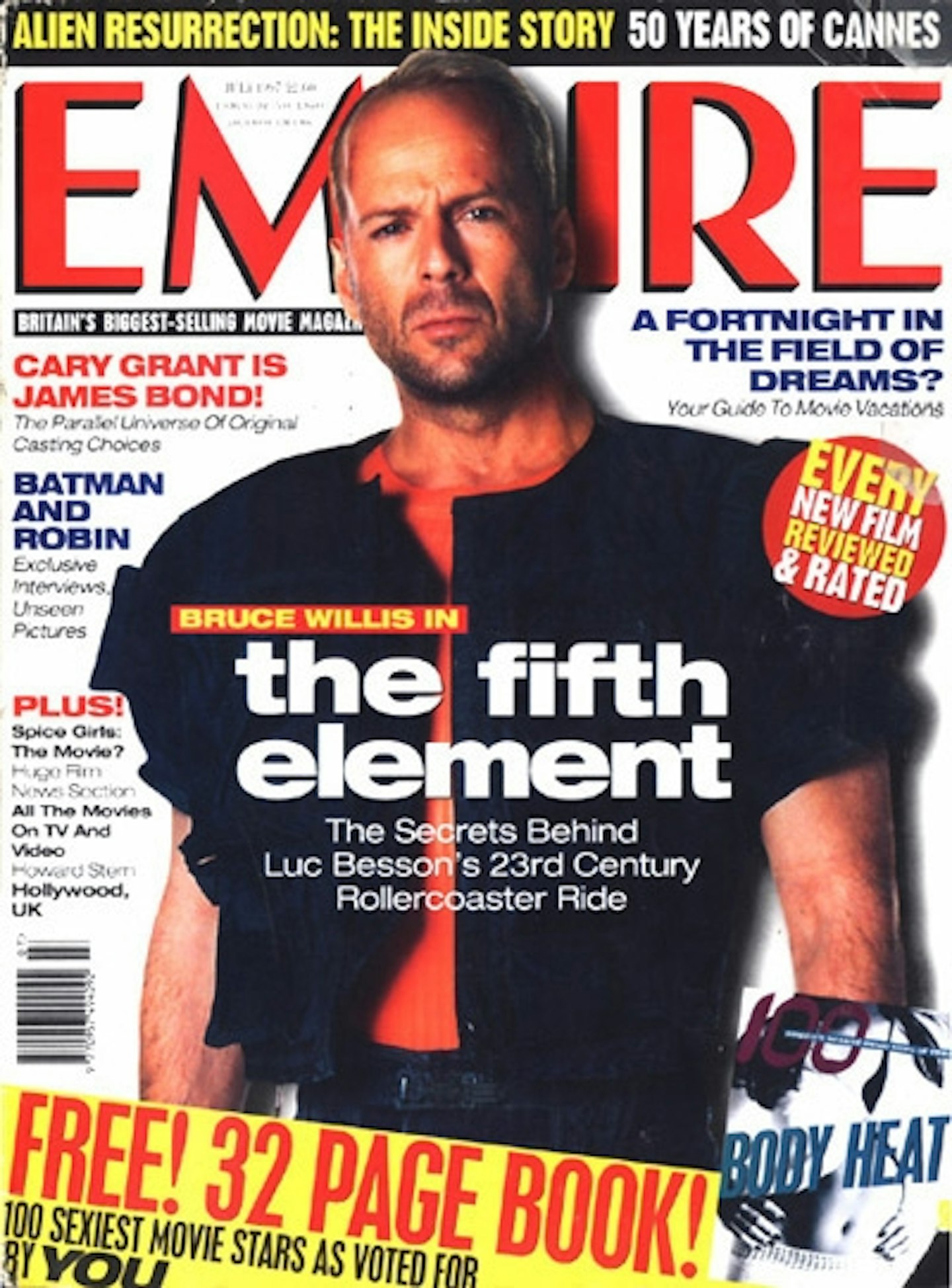

This article originally appeared in Empire magazine, issue #97 (July 1997).

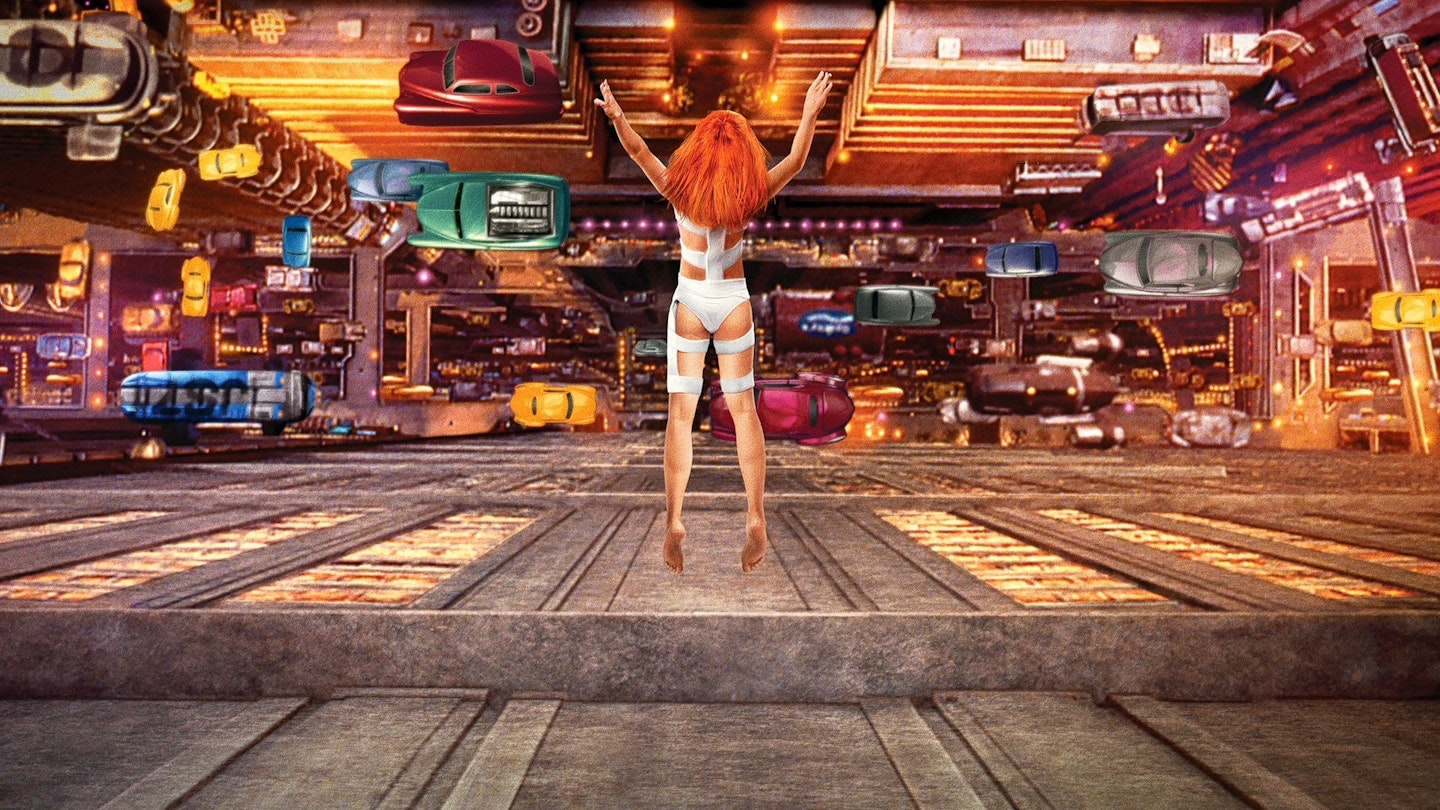

“It was always going to be set here," mutters an obviously knackered Luc Besson, negotiating his way through the diminishing chaos of the tail end of New York's rush hour. "It's just so…" he pauses, glancing at the tangle of yellow-flecked traffic and assembling panhandlers, “intense."

We're on the way to the New York HQ of Fifth Element costume designer Jean-Paul Gaultier for a belated TV interview, and the reason for the director's fatigue is a punishing round of promotional work for his movie – the kind of schedule that befits what will, if there's any justice at all, be one of the hits of the summer – which has thrown a director more used to the sedate life as a generally unknown but cultish auteur into a situation where, in the manner of the international jetsetter; breakfast was in Paris, lunch was in New York and dinner is cooling on a table 2,000 miles away in LA. Intense, would seem, in Besson's case at least, to be an understatement.

I like fashion people. They have a lot of fun.

A few minutes later Empire is uncomfortably ensconced in the world of haute couture. An anonymous-looking door in an unpromising looking building has given way to the coldly stylish environs of Planet Gaultier. Leggy models clad in futuristic airline hostess costumes chat in hushed whispers, cigarettes dangling from perfect mouths; champagne corks pop with languid decadence and a fey Japanese fella; who looks for all the world like the barman from Good Morning Vietnam, glides around the place holding a glass of bubbly with the kind of studied indifference which indicates that this is a hand rarely without a flute of Moet. Things take an even stranger turn when Jean-Paul himself prances in and liberally sprays everyone with his latest perfume, the cloying niff of which he's unjustifiably proud. Frankly, it's hardly Empire's usual stamping ground and, as we're being roundly ignored by all present while Besson sits in front of the Goodnight Pittsburgh (or Wake Up Alberquerque) film crew, let's review the facts.

The offspring of diving instructor parents, Luc Besson spent his early life in flippers. An epiphanic encounter at the age often with a friendly dolphin convinced him that his future was to be spent floating around the Mediterranean as a Delphinidae specialist. It was a dream shattered by a serious (and little talked about) diving accident when he was 17. Asa result Besson turned to cinema and, after educating himself via tapes of the classic movies, began directing adverts before moving onto his first feature, The Last Battle (1983) a post-apocalyptic number shot in black-and-white and (unusually for a first feature) in Cinemascope. In an indication of Besson's preference for visuals over plot or dialogue, it possessed little of the former and none at all of the latter. Subway followed in 1985 and immediately provoked a stormy and somewhat bad-tempered debate in the French critical press, but audiences loved it. It was a pattern to be repeated with The Big Blue (1988). Released in the US in truncated version and with a soundtrack by Bill Conti replacing Serra's original music, it again attracted the wrath of the critics for visual lushness and enigmatic, almost non-existent storyline. Audiences, however, again clamoured for more and Besson responded by restoring footage, replacing the soundtrack and producing a near four-hour version of the film. The Big Blue promptly became France's most commercially successful film and Besson capitalised on his newfound international success with Nikita (1990) and Leon (1994). But brewing in the back of his mind was the sci-fi spectacular that would become The Fifth Element.

“I like fashion people," declares Besson, leaving his chums cooing over a copy of Cosmopolitan and murmuring "Best show in 20 years" like a mantra. "They have a lot of fun."

It's a revealing comment. For if there's been one criticism levelled consistently at the 38-year-old director it's that his films are high on pretty visuals, but low on intellectual clout. His breakthrough movie Subway introduced the world to Christophe Lambert and to a style of cinema with slickly-angled shots and ultra-chic style that in France would come to be dismissed as "Cinéma du Look" – a direct rejection of the weighty film theorising of the likes of New Wave cutting edge directors of the Truffaut/Godard stable.

It's not an accusation that he takes particularly seriously. "People have been talking about La Nouvelle Vague all day," he sighs, looking for all the world like a bleach-blond Gallic Paddington Bear, all earnest shrugs and soulful eyes. "Look, I wasn't even born then."

I always [aim for] humour. We just make movies. We can't be too serious.

Nonetheless, his films do tend to look very nice indeed. Doesn't this disguise a lack of respect for the French tradition of furrowed-brow filmmaking? "With Subway I heard this kind of thing," he remembers. "They were saying it was all aestheticism. But I didn't change one thing about the subway to shoot that film. The subway is like that even now – I just extracted the beauty of the place. Maybe it's my job to tell the ten or 12 million Parisians who use the subway every day: 'You know what? If you just move three feet to the left it can be beautiful. Don't put your head down and look miserable. It can be beautiful, and then your life every morning will be better.”

“I think if it's just the pictures the critics see, if that is what they are more attracted to in my movies, then it's them that have the problem," he muses. "I always try to make a film at two levels - to give food at two levels. One is pretty heavy and about strong things but at the same time I always feel pretentious if I'm just heavy and strong. I always try to get a kind of humour about it. We just make movies. We can't be too serious."

It's not a gripe that's likely to be levelled at his latest, The Fifth Element, an $80 million sci-fi blockbuster with the likes of Bruce Willis and James Cameron's Digital Domain FX group working on the visuals. So what's it like abandoning the cosy world of low-budget shooting in favour of A-list stars and the whole Hollywood schmeer? "Hollywood? I have never made a Hollywood movie. Look, The Fifth Element was funded by Gaumont in France, it was shot in England at Pinewood, all the creative people were French, of the 540 technicians two thirds were English and one third French, and there's a Russian, Englishman and an American in lead roles."

Okay, a European movie then? "It's a movie. Why put a flag on it?" he laments. "The guy who wants to go and see a movie pays his money and he doesn't care where the movie's from. And you know what? He doesn't even care about the director. He just wants to have two hours of pleasure; he wants to see One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest or he wants to see The Jungle Book but above all, he wants to escape. He doesn't care about the nationality of the movie – that's an invention of press people. I mean, nobody asks the nationality of a painting when they go to an art gallery."

Despite Besson's internationalist aspirations, the fact that The Fifth Element is, as we speak, about to open the 50th Cannes Film Festival has raised more than a few hackles in the critical community. "Cannes is a great place to make peace," he says. "If you open with an American movie it's a sign. If you open with a French movie it's a sign. This way, you know, we can forget all these flags and let's have one flag which is Movieland."

It's a magnanimous attitude to take, especially from a man who has been virtually ostracised by the critics in his own country. But it’s one he can afford for, with The Fifth Element, he’s about to be launched onto the directors’ A-list. But directors still forging their reputations can face a rocky path: witness the horrors suffered by David Fincher shooting of Alien 3 and Danny Cannon’s disastrous outing on Judge Dredd. Besson’s blockbuster debut seems to have been unaffected by the money men.

“I’ve made seven movies and never has anyone come onto my set and told me what to do,” he asserts, apparently surprised by the suggestion. “I mean, yeah, they can come. What they gonna say? That they know my work better than me? I’ve been living in the 23rd century for 15 years and they’ve never put a foot there. What can they know?”

We’ll get to the 23rd century in a bit. Promise. But for now, Besson is lurching ever closer to Cantona territory with a simile. “It’s like a sponsor for a boat which is in a round-the-world race. Was the guy who put the money up on board? No. He stayed on the port and says, ‘If you can, call me sometime and tell me where you are.’ And he just prays; he puts a candle in the church and prays that the guy’s going to win. It’s exactly the same when a movie of this size starts. It’s a huge boat sailing towards a storm. So don’t bother the captain.”

Besson sits back apparently well satisfied that kibosh has been well and truly applied to any suggestion that he might capitulate to les monsieurs d’argent in any creative argument. It gives us a moment to explain the 23rd century thing. Because, you see, all day Besson has been claiming that not only has he made a film about the 23rd century, he’s been telling everyone that he’s actually from there. The notoriously irony-free American press have reacted with confusion, some no doubt under the impression that they’re dealing with a Whitley Streiber-style true life abduction case. What, in fact, is the case is that The Fifth Element has been a pet project for Besson since the tender age of 15.

“I escaped from my world to be in this world,” he remembers. “The period between 16 and 18 was not much fun for me. I was too far from the city, living near a forest and I had no friends. It was pretty boring, I was always by myself and it was a way for me to escape. A good way.”

Gary Oldman is the best actor in the world.

The period that Besson started imagining his lush vistas of the future coincided with the time that he discovered that his career under the waves was going to be denied. What emerged from this was a vision of the future he’s been harbouring for nearly two decades and claims to know back to front. Empire tests his knowledge. Is marijuana legal in the future? “There is no more marijuana,” he replies without even the suggestion of thinking about it. “All the drugs come from the outside, from other parts of the galaxy. And you can get everything.” Okay, then. What about religion? Are we still going to church? “There are no religions. All have died out.” No 3D virtual renditions of Praise Be! with Thora Hird, then…

Bringing his dream to the screen took six years of stop-go deal-making with the final commitment of Bruce Willis to the movie, the all-important ‘yes’ coming only two hours after Willis read the script. But how did he react to Besson’s interventionist style? (The director has been known to walk into shots, reposition actors, discuss the scene, and then carry on without ever calling “cut”.)

“All actors react the same way,” he says. “They are always a little surprised. That’s the first day. And they love it the second day because they feel the director is there, concerned, ready to help, aware and they love that because what they want above all is to be aware that you’re there for them. And how can you be more completely there for them than when you’re standing three feet away? I feel like I’m third player in a game who gets so involved that without realizing it, he’ll be in the middle of a field shouting at the players and somebody’ll shout, 'Hey! You’re on the pitch! Get off…'”

If Willis reacted well to Besson’s technique, Gary Oldman positively thrived on it. Indeed, Besson appears to be a founding member of the actor’s fan club. “Gary Oldman is the best actor in the world,” he asserts flatly. “There are a lot of excellent actors, but very cerebral. They need six months to get the sense of the thing. If the guy has to be a garbage collector he has to be a garbage collector for half a year and all this bullshit. With Gary, if you say you’ve got to play a garbage collector he’ll ask what time we start shooting tomorrow and he can play it. Right away. If you ask him to play Hamlet, in a week he can play it. No other actor in the world can do that…”

Enquiries about what he’s currently working on lead to an incredulous glance and his declaring that he needs at least a couple of centuries off before he even thinks of making another film. “I didn’t expect the size,” he admits. “I was a little naïve about that. If I’d known, I’d have prepped myself much more. So, I was already exhausted by the first 10 weeks and then there was another, harder 10 weeks plus six months of editing and six months of special effects.”

Given his exhaustion, talk of a sequel appears inappropriate. But there are, as Spock would have it, always “possibilities”. “I’ve written 400 pages, so there’s enough for another,” he admits, pausing before perking up. “Look, what drives me is the pleasure. Let’s say the movie goes around the world and people really enjoy it and have fun and they say it was cool. That’s the only thing that could drive me into making another one. If people just try to attack me then okay. Don’t worry…” He looks up and smiles. “I’ll just stay home.”

This article originally appeared in Empire magazine, issue #97 (July 1997).