In the latest issue of Empire, we bring readers the full story on the making of Christopher Nolan's hard sci-fi epic Interstellar. As part of our investigation into the film, we asked Nolan about the films that influenced him as he put his story together. Here, for your edification, are the films he named as influences on the story, so be sure to seek them out before Interstellar arrives on November 7. And for much more on the film, pick up the November issue of Empire magazine{

As the grand-daddy of all serious, modern sci-fi, Stanley Kubrick’s cosmic masterpiece is such an obvious entry that it could sit on any list of ‘Films You Should See Before’ *any *upcoming science-fiction. And yet it’s placement here is far from a cop-out.

To begin with, Kubrick is a major influence on Christopher Nolan, period. Nolan has spoken before about the impact 2001** **had on him when he first saw it as a seven year old — an impact which resonates through all the director’s work. Then there are the obvious similarities in the story: a vast journey is undertaken by a small crew with A.I. assistance, which first involves a trek across the solar system then leaps way, way Out There. And, of course, big themes about humanity’s future, and its place in the universe, are tackled.

“Science-fiction fans are going to spot all kinds of references,” Nolan admits to Empire, “but I don’t think it gets in the way of the film. It doesn’t for me, anyway!”

The Endurance, the Interstellar crew’s mothership, is visually reminiscent of the orbital docking station in 2001. Both films get around the ‘artificial gravity’ problem by, literally, putting a spin on their spaceships. And Nolan has knowingly given his two robot characters, CASE and TARS the same rectangular profile as Arthur C. Clarke’s monolith (when they’re in prone form at least)…

While he’s keen his film be as remarkable for its differences to 2001 as for its similarities, Nolan’s not afraid of discussing Interstellar’s influences.

“I think if you try and hide your influence too much, you’re gonna wind up making something insincere,” he says. “You have to do what you love. You don’t sweep it under the rug. I think also, the movies you grow up with, the culture you absorb through the decades, becomes part of your expectations while watching a film. So you can’t make any film in a vacuum. We’re making a science-fiction film… You can’t pretend 2001 doesn’t exist when you’re making Interstellar. You just dive in and do what excites you. There’ll be people who’ll spot every reference along the way, there’ll be some people for whom it’ll seem new and fresh. I think the best you can hope for as a film-maker is that you’ve been respectful towards your influences and you’ve done something fresh with the combination of things that you’ve put together.”

Whoa, easy there. We are not saying there are aliens in Interstellar. There *may *be aliens in Interstellar — who knows? — but that’s not why Ridley Scott’s deep-space stalker-horror has made the list. It’s all about the aesthetic, the approach to the production design. Interstellar is set-based and location-based with a minimum of greenscreen. Its environments are practical, tactile, unapologetically analogue. In other words: Nostromo rather than Prometheus.

“My rule of thumb was we didn’t want any kind of gratuitous futurism in the sets,” says Nolan. “Everything would be functional and feel real to the actors. They could flip the switches and use the control stick and actually have it feel like it means something.” As with 2001, it all goes back to the things that made an impression on him during his formative years.

“For me growing up in the ’70s, the reality of the grit and the grime of films like Alien, or the first Star Wars, those always stuck in my head as being how you need to approach science-fiction. It has to feel *used *— as used and as real as the world we live in. And I didn’t want design for design’s sake. There’s a lot of what I referred to Nathan [Crowley, production designer] as ‘getting a bunch of Styrofoam boxes and spray-painting them silver and sticking them on a wall,’ as if that meant something. Whereas it doesn’t. We tried to approach it from exactly the opposite point of view, which just says: ‘If there’d be a switch here that does something, we’ll put a switch here’.”

For a time, Interstellar** **was a Steven Spielberg film. Spielberg was no doubt as attracted to this story as he’d once been compelled to write Close Encounters, given the fact that his father, Arnold, was an amateur astrophysicist. Plus it’s another grand journey film with a family at its heart… and a father who leaves his family behind to venture into the Great Beyond.

We shouldn’t necessarily be surprised that Nolan was keen to pick the project up after Spielberg left it. After all, he grew up with Spielberg’s films, and was keen to revive an approach to blockbusters that he felt has slipped to the wayside in recent years.

“When you think of Close Encounters, when you think of all his other movies, there’s just a great spirit to them that I wanted to capture,” says Nolan. “There’s a language to those films that’s very classical, almost old-fashioned, and Spielberg and Lucas and all those guys just did it so well.”

They were also family entertainments that, by today’s standards at least, had a hard edge to them.

“Absolutely. Close Encounters is very harsh, in a way,” Nolan agrees. “Harsh realities. But what I loved about some of the best of those films of that period, and what I tried to do with this film, was that whatever the fanciful element of the story was, they were about families. They were about people, about relationships. Not in any kind of tedious or preachy way, but in a really fundamental way that you could relate to. They said something about how we live our lives while introducing the fantastical and the extreme. I think it’s a powerful form of storytelling, and it’s been quite a challenge to embrace that.”

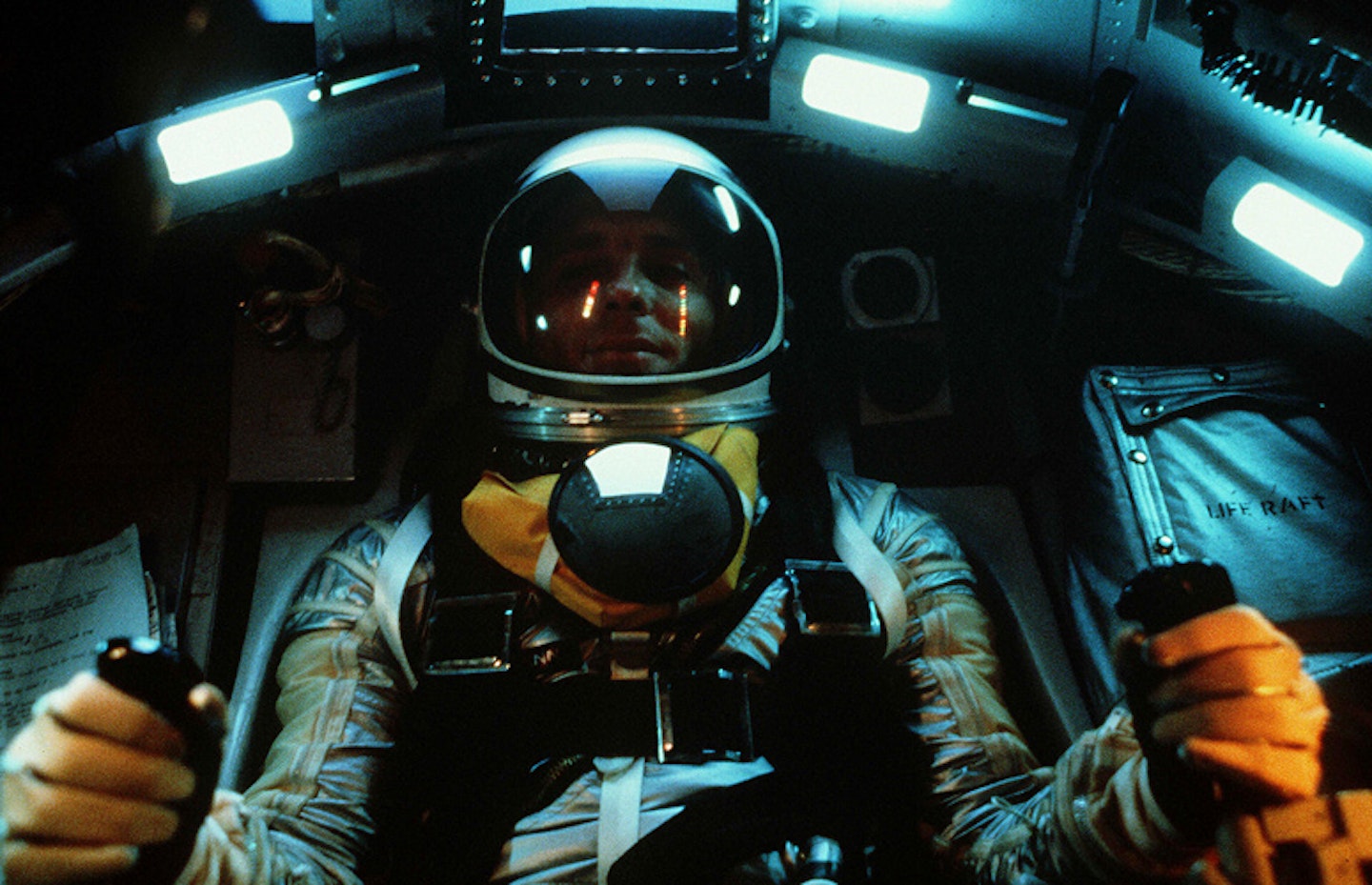

Philip Kaufman’s epic adaptation of the Tom Wolfe book, itself an account of the birth of the US space program, is arguably the biggest, most direct influence on Interstellar. Nolan and his creative team constantly referred back to NASA and the realities of space travel. So just as they visited the California Space Centre to view the Endeavor space shuttle close up, they also sat and watched The Right Stuff, taking detailed notes — on the filmmaking techniques especially.

“At the time, you couldn’t get it on Blu-ray,” laughs Nolan, “and I was actually hassling Warner Home Video to put it out, because it’s a marvellous film. But we screened a print of it. I’ve actually screened two different prints of it. One print was fantastic. What they did in-camera, with all these great projections through windows, so you’ve got the real reflections in the helmets and all that... You know, we just looked at that and I said, ‘Guys, it’s so much easier for us to do that now than it was for them. So we have no excuse not be doing these things in-camera. We can’t just throw it all to the visual effects guys!’ And we didn’t.”

In the form of test-pilot Chuck Yeager (played by Sam Shepard), Nolan also found the ideal for his lead character, Cooper, and through that was driven to cast Shepard’s co-star in Mud** **(produced by a friend of Nolan’s, Aaron Ryder): Matthew McConaughey…

This adaptation of the Carl Sagan novel about humanity’s first communication with extra-terrestrial life has not been cited by Nolan as a direct influence, but it is very relevant to the evolution of Interstellar.

Sagan was friends with Lynda Obst, who first pitched his script idea while working as a studio executive at production company Casablanca FilmWorks all the way back in 1979. Contact languished in development hell, during which time Sagan published the story as a bestselling novel, which in turn helped get it back onto the slate — as a Robert Zemeckis picture, for Warner Bros. Also involved: theoretical physicist Kip Thorne, whose theories about space-travel via wormholes Sagan worked into his story.

A decade or so later, and Thorne himself was pitching Obst, now a big wheel at Paramount. This time he wanted his wormholes front and centre in the story. That story? Interstellar — another big-budget film that tackles big sci-fi concepts with a foot firmly planted in the real world.

The rest, of course, is well chronicled, but then there’s that other connection point: Matthew McConaughey. In Contact, he was cast as minister Palmer Joss (“who represented the belief-in-God part,” in the actor’s own words); in Interstellar he’s the main man, the pilot Cooper. Still, it certainly seems to have primed him for his Nolan adventure: “After Contact,” he says, “I started to really think it would be foolish to not think that there isn’t life out there…”

**Inside the issue you will find Nolan and his cast giving the best indication yet of what we can expect from his secrecy-shrouded science fiction effort. Says Nolan, "It’s a very classically constructed movie, but the freshness of the narrative elements really enhance it. I liken it to the blockbusters I grew up with as a kid, family films in the best sense: edgy, incisive, challenging."