Oscar-winning director Jonathan Demme died this week and what better way to pay tribute to the great man than with an exploration of his most influential work, in his own words. This article first ran in the September 2015 issue of Empire.

On the night of March 30, 1992, beneath the cascading chandeliers of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, the Academy Awards stopped making sense. Jonathan Demme, a few rows from the stage, was flabbergasted.

“We were amazed just to be there,” he recalls. “We knew we weren’t going to get any awards for our horror movie.” that horror movie had so far won Best Actor and Actress, and Adapted Screenplay. Demme saw Warren Beatty lean over to the person next to him and audibly whisper, “it is going to be a sweep.” But he couldn’t believe any of this was happening. then came Best Director, and his name was read out.

“I remember walking across this gigantic, endless stage,” he says. in the far distance was Kevin Costner with a golden statuette and a golden smile, ready to award an astonishing piece of direction. Watch it again: it is such a devious pleasure. The Silence Of The Lambs is one of the great studio movies of the ’90s. here is not only the breadth of Demme’s talent and versatility, but an instinctual desire to take convention to unforeseen, often strange destinations.

Up on stage, giddy with the moment, Demme began his speech. “I wanted to thank everybody I knew, the emerging female directors, African-American directors. Directors who had been good to me and recently died, like Hal Ashby and Martin Ritt.” But he “ran out of gas” before one of the most important people in his career, Demme’s great without-whom, Roger Corman. it still haunts him.

Demme, now 71, reminisces in a flurry of memories, unafraid of revisiting the bumps as well as the sweeps. At college, failing to become a veterinarian, he was a dead-broke movie junkie. Figuring that critics saw movies for free, he applied for the non-existent post of film critic for the University of Florida's campus rag. he parlayed that into being critic for a bi-weekly shopping guide. in London in the late ’60s, he wrote reviews for men’s magazine Club.

“I gave a rave review to Zulu,” he confesses, “which now we look on as

a bit ra-ra.” But when Demme’s hotelier father passed on a copy of that review to Joseph E. Levine, the producer thought he had fabulous taste and offered him a job in the publicity department at embassy Pictures. From there he fell in with new World Pictures. He only became a director because Roger Corman told him to.

The Corman Years (1974-1976)

“I had no aspirations to direct whatsoever, I loved being a publicist,” Demme says matter-of-factly. Keen to stretch the New World payroll as far as humanly possible, and much because he was standing right there, Corman asked him to write a script “about motorcycles”. Later, producing The Hot Box in the Philippines, monsoons having soaked the schedule, Corman informed him he’d just have to shoot second unit himself. He’d been impressed by Giovanni Fago’s Spaghetti Western O Cangaçeiro at a Manila fleapit. So he went back and paid attention. “Who was I most inspired by? Giovanni Fago!”

He would direct three quickies for Corman: Caged Heat (women’s prison), Crazy Mama (’50s crime spree) and Fighting Mad (farmer versus land barons). “It was the most extreme example of conducting your education in public,” Demme laughs. “There is good stuff in there, and plenty of bad.” On Caged Heat, there was this long dolly shot. Such extravagance on a Corman! “Young women racing through the groves firing guns,” he chuckles. “That was when I knew I loved this job.”

Swing Shift & Stop Making Sense (1984)

After a trio of post-Corman films — Citizens Band (CB-radio comedy), Last Embrace (Hitchcockian thriller), Melvin And Howard (Capra-esque fable) — gave signal of a keen ear for scripts and a fine eye for casting, he met Goldie Hawn.

“You’ve got to learn from your bruises,” Demme mulls. Swing Shift was to be a period piece about camaraderie among the ‘Rosie Riveters’ on the factory floors during World War II. Demme had arrived — a $30 million movie with the hottest actress in town! However, Goldie (never “Hawn”) had fallen for co-star Kurt Russell. When they came back from holiday she felt Demme’s cut was a big mistake. “She thought the Goldie-Kurt relationship should be way upfront.” The studio made no bones about whom they were backing. “Private Benjamin had been this gigantic hit,” Demme laments.

Touting for writers to ‘fix’ the movie, Elaine May told them not to touch

a thing. Robert Towne agreed to take it on. “I had to shoot all these new scenes and it was profoundly difficult. I remember sitting in the bathtub, frankly just crying.”

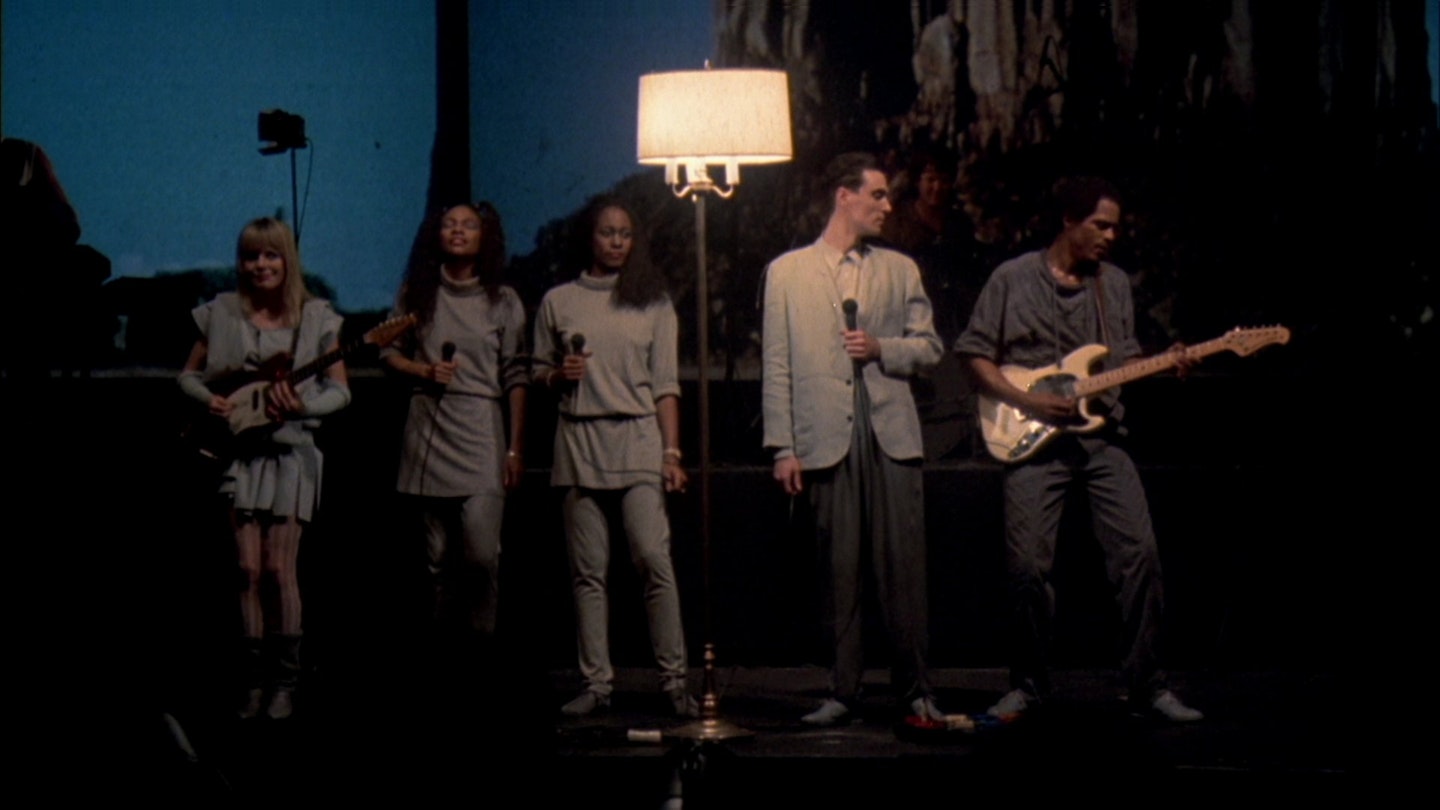

Lessons had been imparted: you’ve got to be able to trust your producers, and you’ve got to have final cut. “You know,” he says, “during that torturous period, I shot Stop Making Sense.” Like any proud New Yorker, Demme was a Talking Heads fan. But he was in LA when they first came to town. Gazing upon the otherworldly David Byrne dancing in an outsized white suit, it struck him: “This is a movie waiting to happen.”

Stop Making Sense is a concert film like no other. No fake audience cutaways, just total concentration on the music being created on this science-fiction stage setting. “That was the last time that band played together before a live audience,” relishes Demme. “And we were there.”

Something Wild & Married To The Mob (1986-1988)

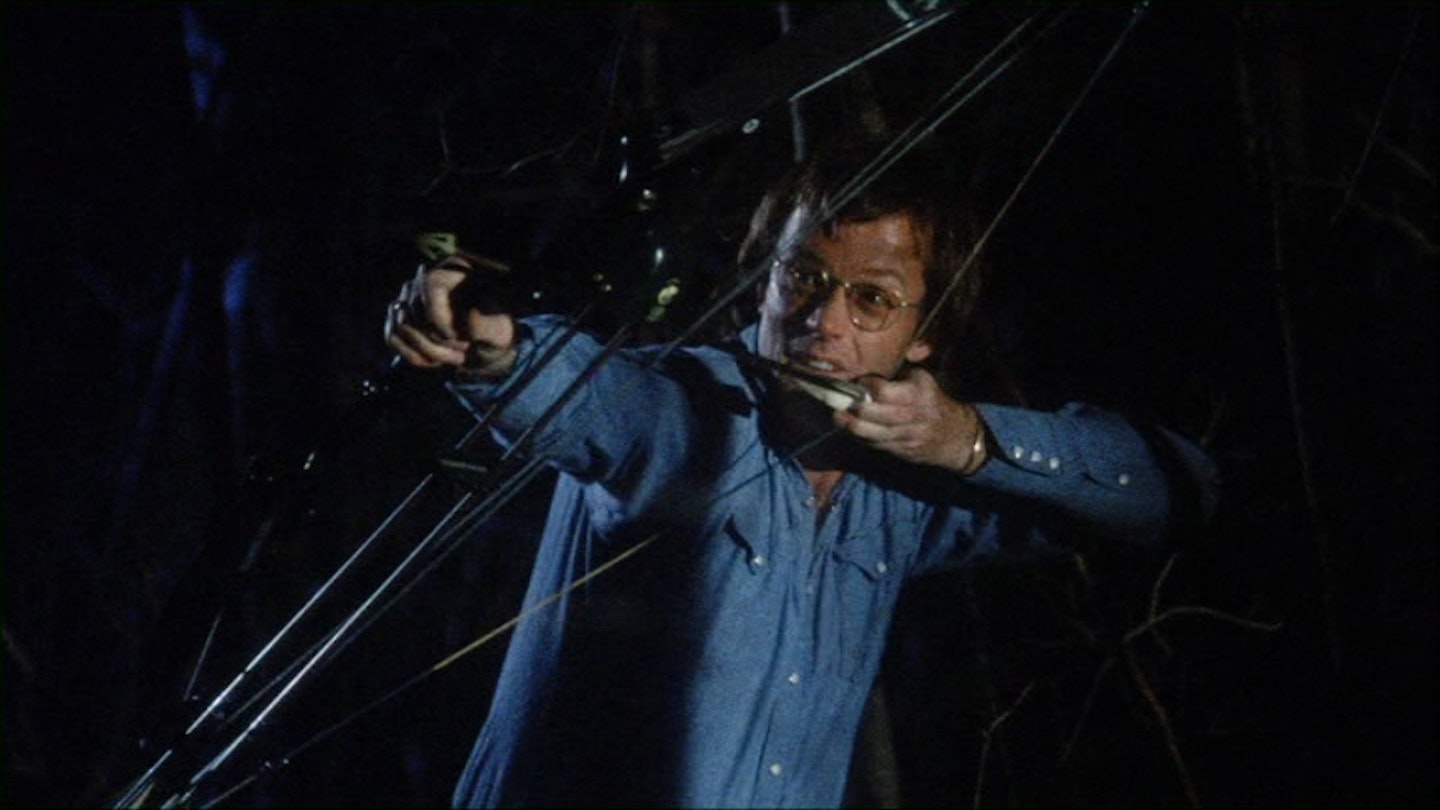

Demme doesn’t talk about theme too much, but the double-bill of off-kilter romcoms that followed sums up something true about his work. “I love the element of surprise,” he says first, trying out self-analysis for size. “The element of a story where you haven’t a clue where it is going. Like with Something Wild, who would ever imagine it ends up where it ends up?” Quite. This frothy, erotically charged comedy, which sees devil-may-care Melanie Griffith kidnap/seduce lonely sap Jeff Daniels, is jittery and exciting exactly because it feels out of control. By the end, when Ray Liotta’s unstable ex shows up, it borders on a thriller.

“And I am a real sucker for the underdog, especially the female underdog,” comes the second thought. It’s there in the wry satire on American materialism, Married To The Mob, in Michelle Pfeiffer’s Mob wife looking to make good after her husband is whacked. It’s there in more recent films like Rachel Getting Married and Ricki And The Flash too: lost souls, difficult maybe, but always heroic. “To this day women are still the underdog,” he says, “in a patriarchal world.”

The Silence Of The Lambs (1991)

Before he began shooting his Oscar-wining thriller, Demme arranged for a screening of effective prequel, Manhunter. “Just due diligence,” he says. Within a minute of Brian Cox’s Lecter coming on screen, he knew it was a mistake and hastily left. “I felt myself being polluted.” He means the way he was thinking about his script, how he imagined Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins in their roles, was being polluted by another sensibility. “I think Brian Cox was great in that movie, I don’t mean polluted in a toxic way.” The two Lecters were not going to be alike.

Sometimes you know when you have a great movie: here was a perfect storm of source novel, adaptation, DP Tak Fujimoto in resplendent form, and these characters as rich and dark as Napoleon brandy: resolute Clarice (Jodie Foster), magnetic Dr. Lecter (Anthony Hopkins), jabbering Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine). But Demme had no idea what it would become. “It was number one in America for weeks and weeks!” That alone was a relief. Nothing he had done previously had been terribly successful and he was beginning to wonder if he had it in him.

Let us not leave out the direction from that list of ingredients, his sublime handling of plot and set-piece: Lecter’s dizzying escape from the courthouse, the night-goggle vision of Clarice blindly stalking Bill through his basement. Of course, Demme, being Demme, puts it all down to casting. “Honestly, and I think this is true of most of my movies, certainly my later movies: you cast brilliant actors and let them bring their characters to it. The film will capture those performances.” It’s something he learned from Corman, honoured with a cameo in Silence — always strive to make your characters fully-fledged human beings. Even fully-fledged cannibals.

Philadelphia & Beloved (1993-1998)

As Demme originally imagined, Philadelphia, the poignant courtroom drama about an AIDS sufferer expelled from his prejudiced law firm, would star Daniel Day-Lewis as Andrew Beckett and Bill Murray or Robin Williams as Joe Miller, the unlikely streetwise lawyer who defends him. He was in search of hearts and minds, a mainstream audience, and a comedian would feel safe. “We weren’t interested in preaching to the choir,” he presses, “our mission was to make a film about AIDS that people who are prejudiced against AIDS would come and see.”

So all those foolish stories that Demme made Philadelphia in response to the homophobic accusations levelled at his previous movie (anger that serial killer Buffalo Bill is a transsexual) are unfounded. “One of my dearest friends in the world had AIDS,” he insists.

Demme and writer Ron Nyswaner were on their 23rd draft when his phone rang. It was an agent: “I have been instructed by my client Tom Hanks to make you aware of his keen interest in Philadelphia and he would like to throw his hat in the ring.” Through gritted teeth, he added, “and he has also instructed me to tell you he will do the film for Screen Actors Guild minimum.”

Then his executive producer, Gary Goetzman, was on a flight sitting next to Denzel Washington, reading the latest draft. Denzel (never “Washington”) asked what it was. Then he asked if he could read it. The next day, Denzel was throwing his hat in the ring.

“So Denzel got on the phone, and I told him we had been thinking about Bill Murray or Robin Williams,” marvels Demme. “And Denzel said, ‘Uh-huh, let me tell you Jon, I can be very, very funny.’”

With more Oscars delivered, and his confidence now riding high, Demme sought even tougher material. Say, how about the slave experience?

Toni Morrison’s Beloved, a disturbing study of the psychological legacy of slavery, is a defining piece of African-American art. Demme’s adaptation is typically brave, confronting its supernatural elements head on (you might consider it his other horror movie) to create an emotionally savage but bizarre ghost story that failed to rouse critics or fans of the book. It centres on Oprah Winfrey’s ex-slave Sethe and the manifestation of her dead baby daughter in the fully-grown but quite possibly undead Beloved, played with a polarising fluctuation of baby talk and animal fury by Thandie Newton. A performance that is either genius, or unwatchable. Buffalo Belle.

“I didn’t do much of anything with Thandie,” Demme confesses. “At the read-through she just sat there with her neck slightly broken, hanging off to one side, using the voice — honestly, I found her, she was remarkable. On set, I didn’t even interact with Thandie. I didn’t want to touch that whole thing.”

The Truth About Charlie & The Manchurian Candidate (2002-2004)

There followed two remakes. The Truth About Charlie is a well- intentioned bagatelle of Euro-glamour even its director thinks a mishmash. “I am still very fond of it,” he sighs.

Here was a chance to go to Paris and remake Cary Grant caper Charade (itself a mishmash) with Thandie Newton and Will Smith, slipping in homages to the French New Wave. Only, Smith got stuck on Ali, and, with a writers’ strike looming, they recast.

“Mark (Wahlberg) and I didn’t really bind together very well,” Demme recalls ruefully. “It really pains me to say this, but I wish we had been able to make it with Will.”

His retelling of The Manchurian Candidate holds up well. It was a chance to work with Denzel again, and throw some mud at the two-party system (Demme describes his political leanings as “old-fashioned hippy”) plus the original wasn’t so sacrosanct.

Best of all, a Manhattan friendship with Meryl Streep flowered into

a creative partnership. Meryl (never “Streep”) gives a priceless rendition of political skulduggery and suppressed rage. Rumours suggested her dark senator was based on Hillary Clinton. “Certainly you can see that,” Demme acknowledges. “But Meryl had her eye on everybody.”

Rachel Getting Married & Ricki And The Flash

You might, at a glance, see Rachel Getting Married and Ricki And The Flash as sister films: a family outsider returns to the fold as a wedding looms and wreaks havoc. But they couldn’t be more different in tone. “Rachel was very aggressively the plight of the recovering alcoholic,” Demme insists. “My own mother was in AA, by the way, at the same age that Annie Hathaway is suffering the mistrust of her family.”

Maybe that is why he chose to shoot his indie drama “like a home movie”. It put the responsibility on the actors, but that is the Demme way — cast then cast-off — and Hathaway, as unlovable wreck Kym, gives her finest performance.

Only after becoming enamoured with Diablo Cody’s dramedic script for Ricki And The Flash did it occur to Demme that they were similar. “These characters were not adorable. You are not forced to fall in love with them.”

Rather than booze, Meryl’s lonely, skittish Ricki is addicted to rock ’n’ roll. She chose a shot at stardom over her three kids. Now, down on her luck, she is called back to the fold when her daughter (real Meryl progeny Mamie Gummer) attempts suicide. “Ricki turns to rock ’n’ roll to give her psychological nourishment,” explains Demme. “I thought it was just vital that Meryl played for real.”

Ricki is a culminaton of Demme: his offbeat Americana, his twisting of genre and love of character. Like Demme, Ricki is a dreamer, a creator, and something wild. And his delight in music played for real in his films (fancy word: “diegetic”) reaches a rapturous crescendo as he mounts a supergroup to play Ricki’s bar band, including Rick Springfield (on lead guitar) and, fittingly, Bernie Worrell (keyboard player with Talking Heads in Stop Making Sense). “To have the audience believe the story, believe these characters,” Demme insists, “you have to have the band really play.”